"I've been watching you all week," he said. "You have a nice smile."

Not at all true.

"You are a good wife and mother."

Even less true; I was there with my adult daughter, a darling blond 22-year-old who didn't need mothering, and I hadn't had a husband around for years. "For Samoans, age isn't important. Only the love is important," he said when I pointed out the blinding difference in our ages. He was a waiter at Aggie Grey's Hotel in Samoa. I was a guest on my last day in the country, and I just wanted to lie by the pool and try not to think about flying away from this paradise. He had been standing in the sun's heat for 45 minutes, holding his tray and trying to persuade me to meet him in my hotel room. I was amused, but not at all tempted. He was sweet, a tall Samoan with a really nice smile and cocoa-colored skin. He was also younger than any of my children -- and seemingly out of his mind. About 6 feet away a retired Australian couple lay silent, lapping it all up.

I've traveled to the South Pacific often, always to the tiny island nation of Samoa. The young men there, in all honesty, are ravishing. Before they settle into their village chiefdom, where the size of their bellies reflects their status, they are gods of the rain forest. As boys they run barely clad through the taro plantations on errands for their elders. They tote water, palm branches and baskets of coconuts suspended on poles that span their widening shoulders. And they climb coconut trees.

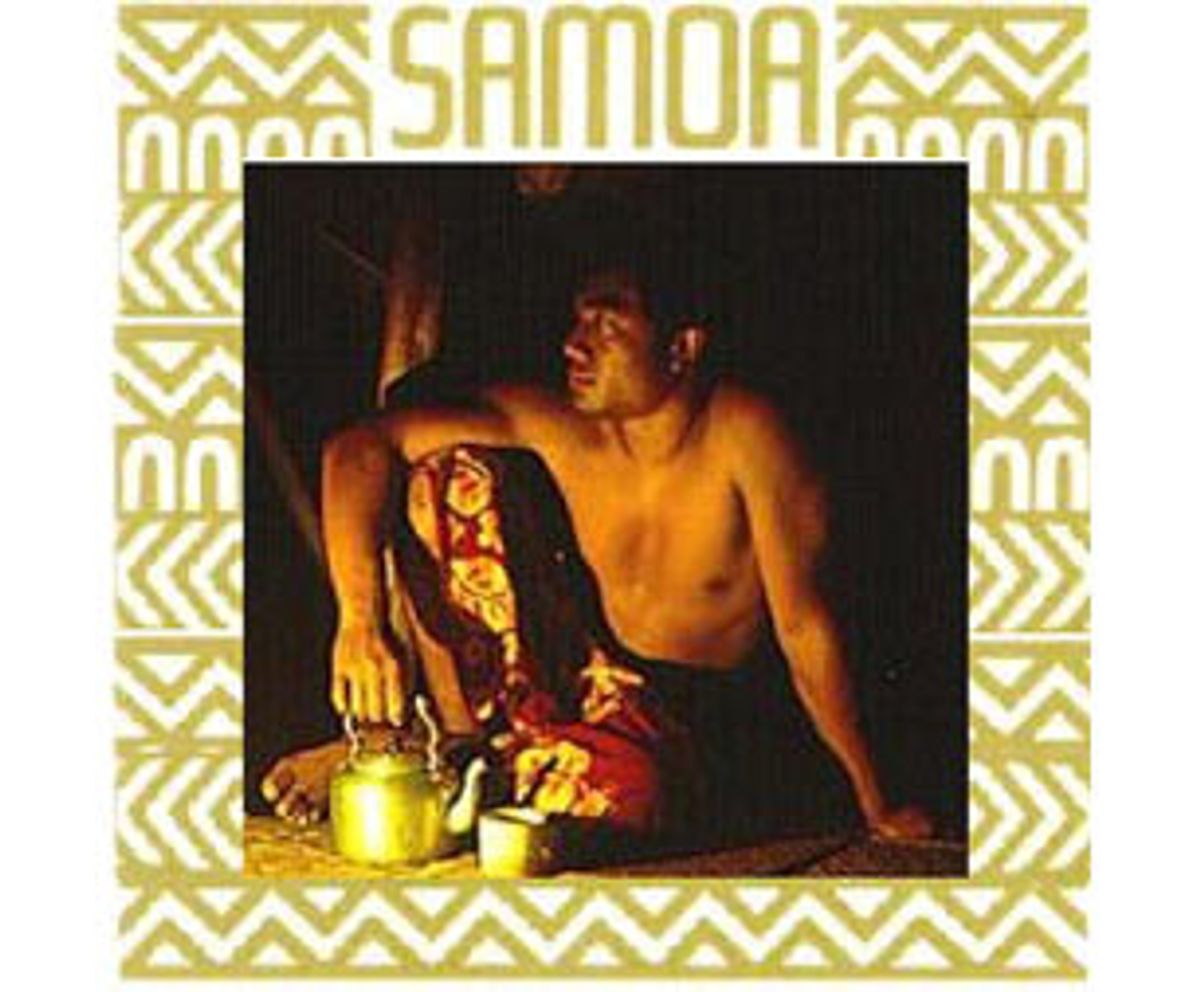

I watched an 8-year-old boy fetch my breakfast one morning: He tied one end of a rag to each ankle to keep his feet about 10 inches apart; then he wrapped his arms around a hairy tree trunk and scampered up in thrusts. Soon the blond nui, the youngest coconuts, dropped and rolled in all directions. It takes any kid there about 90 seconds to whack out a hole in the top of the fruit with his bush knife. The prize is sweet -- creamy, cool coconut milk. These boys, whose small hands become deft at handling bush knives as children, grow to young men with prominent calf muscles and broad backs, black hair and flashing smiles. I'd see them at large along village roads, completely bare except for the brightly colored, saronglike lava lavas knotted at their waists and the large hibiscus flowers stuck behind one ear. They seemed so easy in their bodies, surely ready for any urgency.

These are young men descended from the Samoans whose bush knives cleared a path up the steep side of Mount Vaea in 1894 as they carried Robert Louis Stevenson, that "sailor, home from the sea," to the mountaintop for burial. These are young men who spend hours at sea spearing fish and octopuses, who cut grass by hand, their bush knives doing a mower's work. Many come of age by enduring weeks of tattooing, painfully earning the tatau that covers every inch of their lower body in traditional patterns. And these are young men who sometimes wear "Samoan Power" T-shirts and watch the latest American video violence on TV screens that glow from their open thatched huts late into the night.

But mostly they wear no shirts. They are works of art in their own natural setting, Polynesian possibilities of the imagination.

Most fully grown women who travel outside the United States know how easy it is to attract a man's lingering glance far from home. Once away from the States' tiresomely stylish and annoyingly fit females, normal-size American women who travel to other, more reasonable cultures are valued for their natural and uncontrived charms. It's fun and it's flattering. But when the attention comes from actual boys, it's always so surprising.

During one hourlong wait for takeoff at LAX on a nearly empty plane, I desultorily resisted a young Samoan man's invitations for me to sit beside him for the nine-hour trip to Pago Pago. I had no desire to sit next to anyone when I could have an entire row to myself, and I mostly ignored him. But after he described the tour of the island he had in mind for "us" on our arrival, I finally asked:

"Why are you interested in me? I'm probably your mother's age."

"But I like you."

I asked him if he was attracted to me "because I'm palagi" -- not Samoan. He admitted it was true, saying, "Palagi women have white skin and they know what they want." I thought he might mean they are self-directed, independent women who travel alone and love it, as I do. Then I wondered just what all those other women wanted and how they knew it.

The attention kept coming. A policeman in Apia, the island's only town, stopped me while I was out running early one morning. I trotted right over, thinking he beckoned for official reasons. But he had the all-pervasive question, "How long are you staying?" And then, "Do you go to the nightclub tonight?" And there was Fia Fia, a 19-year-old I interviewed for 10 minutes in an outlying village. A month after I returned home, my mail brought a letter from him, telling me he "wanted to marry up" with me.

Amazing and amusing. But it's not at all like this at home in Northern California. I teach 19-year-old boys; I grade their reading skills and encourage them to develop their essays with specific details. I've simply never thought about taking one of them home. I'd be happy if it were just a bit easier to get dates with a man close to my age -- not necessarily older, but at least a respectable number of years older than my 30-year-old son. But these men aren't as quickly attracted.

Of course, the air's different in California. It's not nearly as heavy and erotically moist. The fish don't fly and glow in the moonlight just below the tranquil Southern Cross. On our West Coast there's no pungent smoke redolent with hemp from cooking fires early in the morning. The cabdrivers aren't named Rambo and don't offer tours of the vicinity "because you make my cab smell good."

After my last trip to the South Pacific, I visited Bali, Indonesia, another tiny island. Though I wasn't really there to check out the men, I couldn't help noticing them. Bali is well known for its compelling beauty, and everything on the island -- both nature's shapes and those made by the Balinese -- seems a gift of a brilliant artist's hand. It's sensually stimulating, but not really sensuous. The Asian men I encountered there seemed so placid. Basically, they were men wearing skirts, men who drove and walked and talked with a sort of spent composure.

Men in Bali showed their interest subtly: a light touch on my arm with every superlative sight the tour guide pointed out, a nearly silent offer to ride out to the temple on the back of a motor scooter, polite questions asking what I thought of the country. Until Nyoman, that is. At first Nyoman seemed like other Balinese men, but he had a playfulness to him I hadn't seen since Samoa. He was about 25 years old and worked at La Taverna Hotel in Sanur. He learned my name as soon as I arrived, and we spoke a few times as he fetched beach towels or icy fruit drinks for me.

Our conversation one evening started so gradually I was completely unprepared. Standing in the dusk of the Balinese night, waiting for my cab, we were both watching some men who'd just arrived and who were excitedly speaking Balinese while waving and pointing to the top of a huge coconut tree right in front of us. I asked Nyoman what they were saying. He told me they were talking about climbing the tree to get coconuts. "Do you ever climb coconut trees, Nyoman?" I asked, filling the languid time with small talk. "Yes, every night," he answered. Thinking that was sort of odd, I replied, "Really?" "Yes," he said, "sometimes seven times in one night." I was still staring up, straining to see the actual coconuts in the branches. I immediately recalled those eager boys in Samoa with their easy skill at mounting coconut trees.

I couldn't turn toward Nyoman; I couldn't let him see I knew what he was really saying. Then I wondered what he was really saying. Still, I stared straight up while he said, closer now, right in my ear: "I'd like to climb the coconut tree with you." Then, like good drama, the cab pulled up and its door opened. I was safe again from the absurd image of consorting with one of my students.

Now I remind myself there's nearly always more happening than meets the eye with these men -- behind their ear flowers, their motor scooters, their bush knives and even their skirts.

Back in the States, as close to the very edge of the continent as I can afford, I fall into my regular lanes of travel to and from work and play. I think about Nyoman's hopeful appreciation and laugh when I remember the waiter's persistence in Samoa. Sometimes I think of how I've admired young men for so long -- all those years I watched Rudy Curinga quarterback my high school's games; the long white seasons I skied the slopes with a trove of guys in college; the constancy of raising a boy to be tall, strong and good. I still spend the whole of my days from August through June accommodating young men's restlessness. I know them so well and feel such affection for their sort. It's like the ability most of us have to appreciate fine art without wanting or needing to live with it. I recognize quality; I just don't want to buy all of it.

And more and more lately, as the gravity of my own age nudges me, as I realize how limited women of my generation feel, I find I don't really want a 19-year-old boy of my own. I want to be one.

Shares