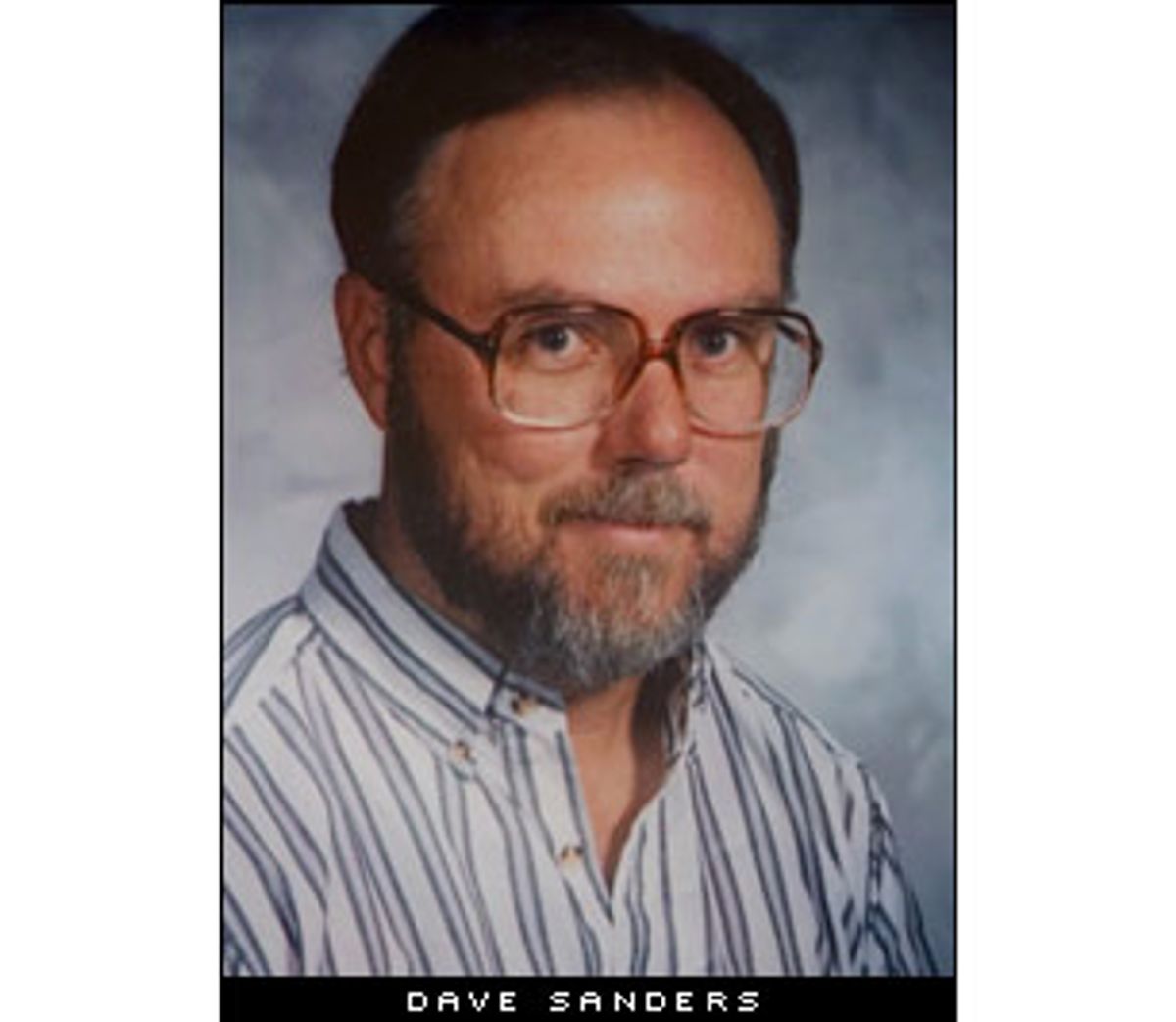

One day after filing a federal lawsuit against the Jefferson County

Sheriff's Department, the lead lawyer representing the family

of slain Columbine High School teacher Dave Sanders charged the

department with a coverup Thursday,

alleging that officials have kept

details of exactly what went on last

April 20 from victims' families and the

public.

"On at least one particular item, I

affirmatively believe they were involved

in a coverup," Peter Grenier said.

"Absolutely, yes. A human being directly

told us that," he said. "A human being

affirmatively demonstrated a coverup."

He said the department has been

extremely uncooperative, forcing the

family to hire private detectives. "Our

case is based on a lot of lengthy,

expensive private investigation," he

said. "No one from the sheriff's office

would tell us anything."

The Sanders lawsuit contained a host of

major new allegations, including claims

that a sharpshooter had Dylan Klebold in

his sights in the library, but his

supervisors wouldn't allow him to act.

It also contends the sharpshooter saw

Klebold and Eric Harris commit suicide,

and thus officers were aware the pair

were dead three hours before Sanders

died, but failed to rescue him.

Because of confidentiality agreements,

Grenier said he was unable to be

specific about the identity of the

sharpshooter, the item covered up or the

witness to it. "It will all come out in

discovery," he said.

Earlier this week a judicial ruling

granted the 15 families who were

preparing lawsuits access to the

sheriff's long-delayed "Final Report,"

but Grenier says the ruling came far too

late to inform his filing. Neither the

Sanders family nor its legal team has

seen the report or the other newly

available material. He expects to

discover additional surprises within

that data. "I hope to God there's

something useful," he said.

Many victims' families have expressed

anger about the long delay in releasing

the final report on the Columbine

investigation. Brian Rohrbough, father

of Daniel Rohrbough, recently lamented

on NBC News that he feared he would have

to sue the sheriff's office to learn how

his son died.

Sam Kamin, a law professor at the

University of Denver, said the various

lawsuits may well achieve their stated

goal of bringing new evidence to the

public. "If this gets far enough that

they do discovery, more information

about this may come to light," he said.

However, the families may be

facing an uphill battle, he said, stressing that he had not read the suits and

was offering a preliminary reaction based

on knowing key points.

"It's going to be difficult," Kamin

said. "It's going to be tough to ask a

jury to say we know better than a SWAT

team how to handle this situation."

The Sanders suit runs over 40 pages,

with explicit, detailed information and

allegations not previously aired.

The suit charges that the sheriff's

office has mischaracterized the attack

for the past year as a "hostage

situation," when "the massacre was not

at any point a 'hostage situation' under

the clear meaning of the term set forth

in Defendants' own manual."

It also alleges that the command team

"knew before noon (although they have

since tried to suggest otherwise) that

there were two suspects, and that their

names were Eric Harris and Dylan

Klebold." The suit explains that the

sheriff's deputy serving as security

guard at the school knew both killers,

and exchanged fire with them outside the

school at the start of the attack.

A sharpshooter witnessed the killers'

suicides, the suit claims, and therefore

"the Command Defendants knew of their

deaths to a virtual certainty by 12:30

p.m. at the latest."

That early knowledge of the killers'

identities and their deaths changed

the nature of the attack, and the

expectations of the law enforcement

response, the suit contends.

While the new allegations about the law

enforcement response to the massacre

have received the most attention, they

are not the heart of the legal case. The

family is claiming that Sanders' civil

rights were violated "by prohibiting or

impeding movement and then not doing

anything to save him," Grenier

explained. The suit hinges on the fact

that the command team forced Sanders to

remain inside Science Room 3, cut off

several avenues of escape, repeatedly

offered assurances that help would

arrive within 15 minutes and then failed

to respond as promised.

"Command Defendants exerted their

control over everyone inside the school

and over the hundreds of police, medical

and rescue personnel massed nearby to

prevent anyone from taking any action

directed at rescuing or saving the life

of Dave Sanders," the suit reads. It

contends the command team prohibited

students and teachers from breaking out

a window and barred SWAT teams from

attempting a surgical entry through the

roof or one of many exterior doors

almost directly beneath him.

"As a result ... Science Room 3 was the

last [their emphasis] area in the

building reached by SWAT teams ... and

Dave Sanders was literally the

last wounded person whom police

or rescue personnel got to, even though

Sanders was the only individual

known to the Command Defendants

throughout the critical several-hour

period to be in urgent need of emergency

lifesaving treatment."

The suit repeats what has long been

common knowledge, that by noon law

enforcement was aware of Sanders'

situation and location via 911 calls and

a large white message board reading "1

BLEEDING TO DEATH" facing toward the

window. The department has contended

that Sanders' wounds were severe enough

that he would not have survived

regardless, but the suit also challenges

this claim.

The lawsuit by the family of Daniel

Rohrbough and four other slain

students also charges law enforcement

teams with inaction on the day

of the killings. "Although numerous

deputies of the Sheriff

Department were in a position to

exchange gunshots with Harris and

Klebold when they exited the school

building, once again Defendants

failed to either stop them outside the

school or pursue the killers

into the school," it says.

The suit paints even Harris and Klebold

as perplexed by the inaction.

"Several minutes after first entering

the library, one of the killers

went to the windows of the library and

shot out several windows," it

reads. "The Defendants made no response.

Even the killers appeared

puzzled and amazed at the Sheriff

Department's non-response to their

rampage."

But the heart of this lawsuit lies in

its laying out a picture of two

contradictory responses: the SWAT teams

remaining outside to "secure

the perimeter" while the 911 operators

instructed students to remain

inside because there was "help on the

way."

"At the time the shooting began in the

library, the students and

teachers inside the library could have

easily escaped to the outside

of the building," the suit contends.

"However, the 911 operator ...

advised [teacher] Patti Nielson that

Sheriff's deputies employed by

Defendant Stone, paramedics and firemen

would soon be arriving in the

library and to stay there and on the

line with her."

But the command team had full intention

of carrying out a very

different plan, the suit contends. After

the killers entered the

building, but before they entered the

library, the command team "made

a deliberate and intentional decision to

limit the response of law

enforcement officers at the school to

'securing the perimeter,'" it

reads.

The result, it says, was the slaughter

of 10 of the 13 victims

murdered April 20.

Kamin stressed that a federal civil

rights lawsuit requires

evidence that law enforcement was not

just ineffective but

made the students worse off than if it

had never shown up on the

scene. The lawsuit addresses that issue

directly: "By way of

comparison, the children in the commons

area (who were not encumbered

by the 911 operator's commands)

scattered to the various exits at the

beginning of the incident and as a

result none of these children were

killed."

As with the Sanders case, this suit

contends that the students' civil

rights were violated because their own

actions were impeded by law

enforcement, who thereby assumed a

special obligation to rescue them.

"By telling the people in the school

library to stay there and await

law enforcement personnel ... [the

Defendants] assumed an

affirmative Constitutional obligation to

protect those persons," it

says. "By such conduct, the persons in

the library were effectively

in the custody of Defendants."

Kamin described one additional hurdle

for this suit. "The

department can't be sued unless it has a

policy or pattern and

practice that violates their civil

rights." That explains the suit's

otherwise surprising conclusion that

both the SWAT teams and 911

operators acted exactly as they were

trained to act.

It concludes by citing that

contradictory training as the crucial

final point in its claim. "As a result,

on April 20, 1999, sheriff's

deputies who chased Harris and Klebold

into Columbine High School and

911 operators who instructed Patti

Nielson and sheriff's dispatchers

were not properly trained to handle the

situation at Columbine High

School."

Shares