It's 1959 and Louis Allan Reed is acting up. If it's not the 17-year-old's mood swings or the bad grades, it's his recent displays of homosexual behavior. At their wit's end, his parents give him what any other strict, conservative Jewish parents in middle-class Brooklyn would: electroshock therapy.

Three times a week, for eight weeks, Reed went to the Creedmore State Psychiatric Hospital for his dose of high voltage. The treatment is deadening. "You can't read a book because you get to Page 17 and you have to go right back to Page 1 again," Reed once recalled. "If you walked around the block, you forgot where you were."

More than 40 years later, one looks at the life-as-art rock star, and that singular, imploring, reptilian look in his eye -- he has said no one does Lou Reed like Lou Reed -- and one wonders if 24 sessions was enough.

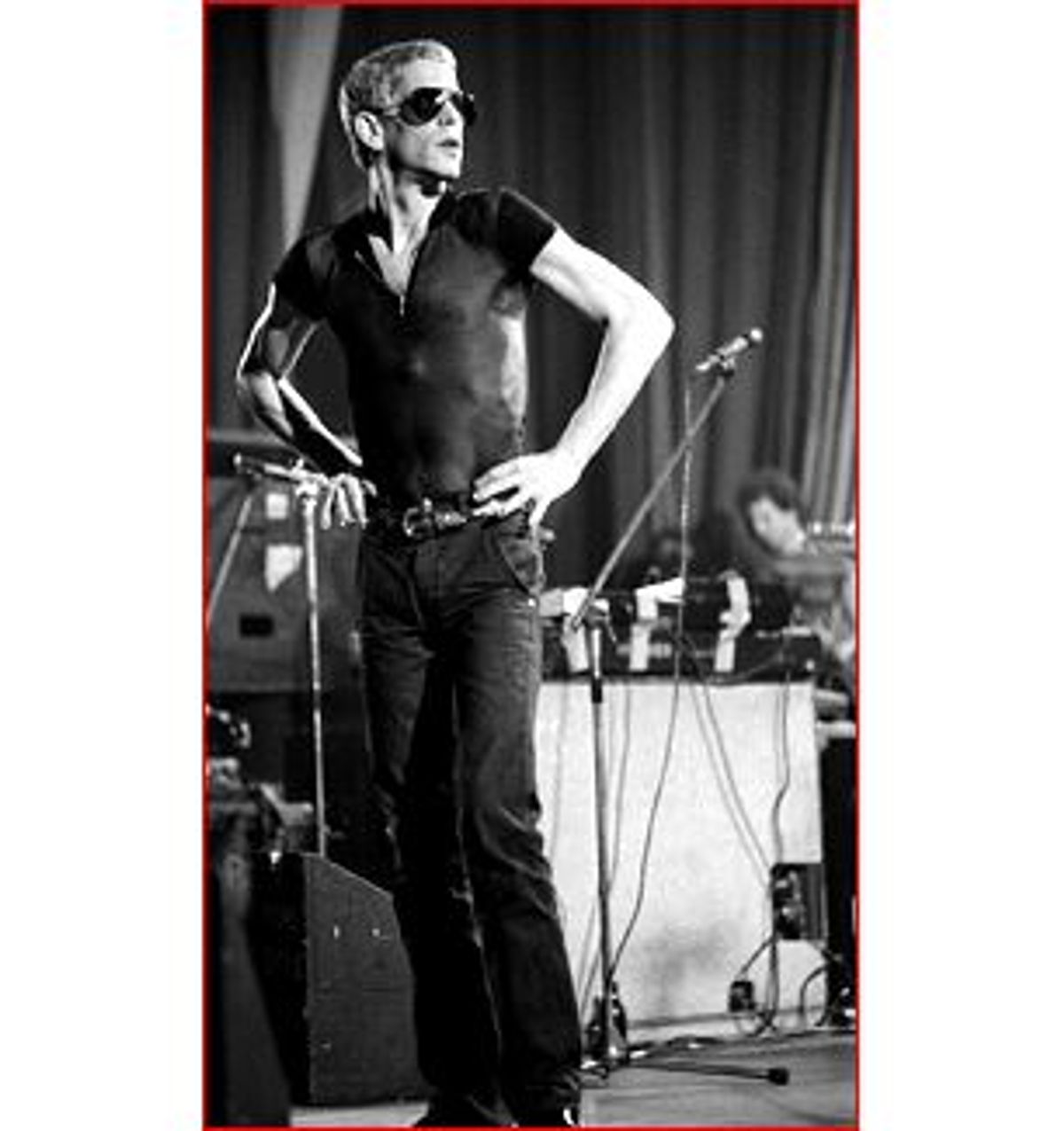

We take Lou Reed for a god. Not a benevolent one, necessarily -- maybe not even a musical one. But look at how he stands there, in his black T-shirt and black jeans and wire-rim glasses and ugly snarl. Didn't the Greeks have a god of attitude? The one who flew too close to the sun but then, instead of falling to the sea, flew even closer because he didn't give a fuck? The 57-year-old founder of the Velvet Underground would have us believe no less.

The world first heard of Reed in the late '60s, in connection with the Velvet Underground, the band the world had never heard of anyway. In the years since their quiet disintegration in 1970, the Velvets assumed a mythology that easily made up for the legions of fans they never had in their non-heyday. Reed and his former band mates -- John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker -- inspired the kinds of legends even the Beatles couldn't hope for: They were the greatest rock stars whom no one ever listened to, the most popular group that never sold a record and, famously, the band that had only 500 fans, but from whom 500 new bands sprung.

Thirty-six years after the first gig, these legends are more than hokey -- they're immaterial. Not only have the Velvets secured their spot in rock history, they've grabbed such a prominent one that we can barely imagine the days of their famous obscurity. "Sweet Jane," "Pale Blue Eyes," "Heroin," "Femme Fatale," "I'm Waiting for the Man" -- these VU originals passed through the realm of classics long ago, and have drifted almost irretrievably into the land of the overplayed, overcovered and overremembered.

Reed doesn't care. If the world never spoke of the Velvets again, he would probably be happy. Or mad. Or uptight. Or indifferent. Whatever it is that he already is. This is the problem with Reed, and has been since the electroshock therapy days: No one really knows what to do with him. At once pretentious and humble, uncaring and epiphanic, faggy and rough, rock 'n' roll's most famous junkie keeps breaking molds.

That's not hot air. He was an iconoclast as early as college, from 1960 to 1964 -- as an undergrad at Syracuse University, he wrote "Heroin," maybe the Velvets' greatest song -- and only proceeded to get farther out. Later, once the band was together, he began putting together material that turned rock 'n' roll on its ear. Over spare melodies but full sound, he sung/spoke/muttered about drugs, S&M, transvestism and other aspects of his Lower East Side life. They were often banalities -- the walk up the stairs to meet the dealer; the name of the street so-and-so had to run down -- but they were banalities that rang with religiosity. It's nothing short of euphoria when he meets his dealer, gets the heroin and heads back downtown. Not since has anyone made euphoria sound so good and so lonely.

The Velvet Underground played some great songs. They occasionally relied on the kindness of spaced-out strangers -- now and then, it took patience to invest in the requisite VU trance -- but even then, it was good music. But they were not the Beatles, not the Stones, not even the little finger of the Beatles or the Stones. As good and new as their songs could be, it was hardly their material alone that brought them fame. The Velvets had a patron who could do P.R. tricks in his sleep.

It was the last night of the band's first regular gig when Andy Warhol strolled into the Greenwich Village tourist bar where they were playing. As out-of-towners politely sipped umbrella drinks, Reed sang about masochism and overdoses. Warhol swooned. Soon the conceptual artist had a band to manage, and the band had an image to cultivate.

Plus money. Warhol's success as a commercial artist meant the Velvets had electricity for their amps and a ready-made stable of potential fans. With Warhol came the Factory, which in turn brought clout. The Union Square loft where Warhol's art was mass-produced was already the center of the universe. The artsy, the hip and the strung-out all mingled in frenetic orbit around the Factory and its joyful contempt for bourgeois culture -- to be at the center of a Factory happening was to be made, coronated. These recluses with cheap guitars and a drummer who played standing up -- they were now Art.

In good conscience, we can credit Reed with maybe 20 really terrific songs. That's no brilliant career. The mark he leaves on us is, rather, about coolness. He's so cool. Him in those sunglasses in the Velvets; him in S/M gear in the '70s; him in the '80s saying "Take it, Lou" before playing his solo on "Beginning of a Great Adventure"; him in the '90s taking Czech Republic President Vaclav Havel and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright to the Knitting Factory to see John Zorn.

Nastiness constituted a large chunk of his charm. He would curse at his audiences, curse at the critics -- he once mortified band mates with a Stalinist salute to a crowd in Europe. All this only confirms that we insist on seeing genius in an artist's hatred of us, or perhaps in our own loving of an artist hating us. And there's his perseverance, too: We adore the tenacity of an artist who continues to drag out this terrific rock clichi year after year, sneer after sneer.

Like the best coolnesses, Reed's layers vanity and indignation with a kind of innocence too simple for layers in the first place. It's a leather jacket in the summer; it's chain smoking cigarettes he didn't pay for. And just when you're ready to roll your eyes, he knocks you over with an earnestness that makes you want to give him more cigarettes.

Along the way, the coolness rose to the level of Importance. Whereas his early enthusiasm for heroin was briefly radical, it was his subtler message about sexuality that continued to stand out: Elton John might've made it OK to be a gay musician, and maybe David Bowie made it cool, but Reed said faggy could be tough. He took all the machismo of simple, fuzz-toned power chords and mixed them with mascara. And the mascara didn't say, "Accept me." -- it said, "Go to hell."

Maybe more than with any other musician, Reed's image is inseparable from his music. The same art/macho creation, the same white-hot frigidity we see in his posturing comes through every note of a Velvet Underground album. The songs are tough and loud, vocals clipping every other verse and guitars seldom in tune. Like Reed, they offer the illusion of not caring; in reality, he and his music are carefully crafted.

Reed is a charming bully. Like the wrong song and you're a fool; ask about the meaning of some lyrics and he'll end the conversation. The Velvets played with a similar brazenness. Listen to "What Goes On": The chords D, C and G form a song in the key of G, meaning that resolution to the progression comes only with the G chord. But the band doesn't play it that way. Through sheer insistence -- emphasizing the D rather than the G -- they force the resolution in the wrong place. And it works; somehow, the song doesn't sound odd at all, and in fact is a real toe-tapper. It was a strange power the Velvets had over their listeners.

But such technical trivia generally remains the domain of more musically sophisticated acts like Steely Dan or Led Zeppelin; VU fans, for the most part, respond to the words. Like Bob Dylan, Reed is often regarded as a poet who happens to play guitar. As chief lyricist, he always claimed that his lyrics neither endorsed nor rejected any particular notion. "Heroin," the song most picked on by prudish critics, supposedly didn't encourage use of the drug, only stated that this was simply a fact of life for some.

Much is said about the VU's ability to put a bony finger on such unsung tropes as grit, hopelessness and confusion. This is a miscalculation. Johnny Cash and B.B. King knew of bleakness when Reed was still trying on sunglasses. What distinguishes the Velvets here is, rather, their approach to these themes: Where those other songwriters arrived at bleakness over the course of a song, this was a foregone conclusion for the VU; their albums began on the edge and simply proceeded to crawl around the other side for the next 45 minutes.

Herein lies the appeal. Listen to VU fans -- they are legion at this point and always outspoken -- explain the phenomenon of first hearing the band play. Consistently, they refer to a revolutionary honesty within the lyrics. Cale once described the effect:

"All Bob Dylan was singing was questions -- how many miles? and all that. I didn't want to hear any more questions," Cale said. "Give me some tough social situations and show that answers are possible. And sure enough, 'Heroin' was one of them. It wasn't sorry for itself."

More fiercely than in any other art, rock stars jockey for the distinction of telling it like it is. There's no room for plurality, for saying, well, Dylan tells it like this and Reed tells it like that. There's only one It in the business, and everything else necessarily falls short.

Reed's raw brand of poetry has been permanently yoked, in rock history consciousness, with such characterizations as honest, direct, open and, most troubling, authentic. Grit, these characterizations insist, is somehow more "real" than prettiness. Such unexamined distinctions inform a fascinating perspective on the cultural moment the VU flagged: The Doors, Simon & Garfunkel, Dylan, the Beatles -- these guys weren't doing it for everybody, and the VU picked up where they left off.

These ideas about truth and authenticity helped shove the Velvet Underground into the realm of high art. Warhol contributed light shows and the contagious conviction that this was the new new thing. At Factory happenings, it became clear that the Velvets were on some sort of vanguard. Their reputation among the un-hip for being vulgar -- born largely of their rumored penchant for sexual deviation -- only confirmed their art-noise value.

In "Duck Soup," Groucho Marx says, "He may look like an idiot and talk like an idiot but don't let that fool you. He really is an idiot." Similarly, the small-but-intense infatuation with the Velvets' newness occasionally obscured the fact that the music was really good. Tucker pounded out a spare, rocking rhythm; Morrison, Cale and Reed played great, fuzzed-out, thin guitar lines and Cale's electric viola and organ buoyed the music with a trance-like drone. The songs were hypnotically simple. For a while, the band even held a ban on bluesy riffs; anyone who introduced one had to pay a fine.

Behind the music, things weren't so fluid. The success had surprised everyone, and personalities clashed. Reed, it's said, could fill an auditorium with his ego. Though Cale had far more training as a musician, Reed generally set the tone. The charming bully could also just be a bully. The story is familiar: creative differences, personality conflicts and different ideas about direction. In 1968, after the release of the second album, "White Light/White Heat," Reed called a meeting with Morrison and Tucker to announce his firing of Cale.

It's difficult to locate the precise beginning of the end. Warhol, though a close friend of Reed's, had also been let go. Without Cale, things never sounded the same -- his viola and organ had added the creepy hum that gave the Velvets their unique sound. The band continued to play, releasing "The Velvet Underground" in 1969 and "Loaded" in 1970. After "Loaded," Reed left. Some say he wanted to pursue a solo career; others point to tensions with Morrison. Without their frontman, the band soon dissolved.

Rather than hover around his legend, invoking it from time to time when his star sinks a little, Reed pushed ever forward. He released 12 albums in the '70s. A few became classics -- songs such as "Vicious," "Walk on the Wild Side" and "Sally Can't Dance" got big -- and many fell flat. He experimented more than the Velvets had, too. "Metal Machine Music" came out in 1975, for example, and stands as a collection of atonal guitar screechings and electronic noise, unleashing his magnificent nastiness.

In the '80s, Reed tamed his Rock 'n' Roll Animal alter ego down to something more thoughtful. "New York," released in 1989, offers a beautiful and epic tour of his favorite city, from welfare kids to the havoc wreaked by drug abuse. The songwriter who'd eschewed the optimism of the '60s now showed no trace of detachment. His participation in Amnesty International events seemed to confirm that even crusty old curmudgeons could hold deep wells of sympathy beneath their leather. In the following years, he published "Magic and Loss" and then, briefly reunited with Cale, "Songs for Drella," a gentle and compassionate tribute to Warhol. A kinder, gentler Lou had emerged.

(It makes sense, if relationships can be said to make sense, that the new Reed has recently married the new Laurie Anderson. Not only do the two represent New York cool, they represent old New York cool. Like Reed, Anderson has evolved from '70s downtown art rogue to something far mellower in our minds; these days, we think of the revolutionary performance artist as something close to a folk hero.)

Transcendence and all, it took some time for America to make up its mind about Reed. (Europe is another story; like jazz, he's always had some of his greatest fans across the pond. Havel has claimed his music played a "special special role" in the liberation of the Czech Republic.) The guy whose songs were once banned on the radio had, under our noses, become loved and even respected. Critics scrutinized his every move -- his lyrics, his sexuality, his drug use -- almost as though they were taunting him: Where is the asshole who used to call us assholes?

Indeed, Reed has forged an ambivalent relationship with critical attention. In true Reed fashion, he used the limelight to spurn all the limelight. He'd agree to interviews and then proceed to abuse the interviewer. He's no recluse -- as much as he resented mass media and all its trappings, his career thrived on it, and he never forgot.

Somehow, his responses to the press are endearing. You can almost picture Reed with a daisy: I love them, I love them not; I love them, I love them not. (Except, of course, that it's impossible to imagine the Rock 'n' Roll Animal anywhere near a flower; if he actually held one, he would certainly smoke it, or at least give it a lecture.)

What the critics, and Reed himself, often miss is that his finest work is the cast of characters he's concocted over the years. The music was often, and can still be, great -- his latest album, "Ecstasy," came out in April to favorable reviews. But the thing that entrenched itself was the attitude, the theatrics. It was a schizophrenic attitude, too, full of revisions, and the energy of schizophrenia never failed to charge his performances.

Like Bowie, Reed cultivated a variety of characters for himself to inhabit over the years. He could be the glam, blond pretty boy, the vicious sadist, the cantankerous preacher and, a perennial favorite, the snide New Yorker. He either defiantly resists pop with dark, non-radio jams or he purports to transcend it with self-consciousness, cutting the earnestness of a catchy pop tune with those cold eyes and those fuck-you cheekbones. But it's still a catchy pop tune. "Sweet Jane"? Those chords snap and thrum like beautiful rubber bands.

"Ecstasy" returns to this territory, or at least closer than Reed's been in a while. Again, he presents variations on the theme of transcendence. He has suggested that he's demonstrated enough musical and lyrical variety (in, say, "Songs for Drella" and "Magic and Loss") to earn a return to classic Lou Reed. The songs are familiarly filmic, telling stories that rely on powerful -- often melodramatic -- images, and a cast of characters whose rough edges sparkle for a fleeting moment. It's that strange mix of heavy-handed and pluralistic we've come to expect: A man has his nipples sucked by whores, and that's OK.

"Strange mix" is one way to put it; another is conspicuously inconsistent. So maybe we like Reed for his contradictions and flaws, and for the fact that he doesn't know why we like him. That's rock 'n' roll, after all: all innocence and rudeness, too dumb to be cunning and too bad to be bad.

Of course, beautiful dumbness isn't enough -- we require of our musical greats some kind of human understanding, too. Reed has always understood our heads, in some strange way: There are symphonies in there. Some are written by others -- Mozart, the Beatles, Monk -- and they got there because they're perfect. They play at perfect times: when we're on our bikes in the sun, or jumping into the shimmering lake or walking home from the bar where we toasted life with friends.

But we hear other music, too -- imperfect notes we piece together ourselves from secret brain reservoirs. These soundtracks play when no other seems appropriate. Stepping out into the sun on a winter day and feeling a rusty screw in your heart, and sweating, wondering what your drugs were cut with, fearing this is the day you drop dead in a frothing heap on the way to the drugstore -- in these moments, Lennon and McCartney don't do the trick.

So we devise an accompaniment, too messy to be called music, and this is what Reed often touches. His songs sound like blissful death, other times nothing so elegant. They rub the private music that rises and falls with the beat of the ecstatic, broken heart. It's the walk home from the bar, yes, but punctuated with miserable retching in an alley; it's the jump in the shimmering lake only to find that quietly fluttering to the bottom is a strangely real option; and the bike in the sun? Well, the sun is black as hash.

Shares