Robert Towne was known as the legendary script doctor who did the final rewrite on "Bonnie and Clyde" and contributed a crucial scene to "The Godfather" before he became a screenwriting giant with a whole string of '70s classics. In "The Last Detail," "Chinatown" and "Shampoo," Towne brought a new demotic frankness to hard-boiled genres and romantic comedy. But few films in his career posed challenges thornier than those of "M:I-2," the sequel to "Mission: Impossible."

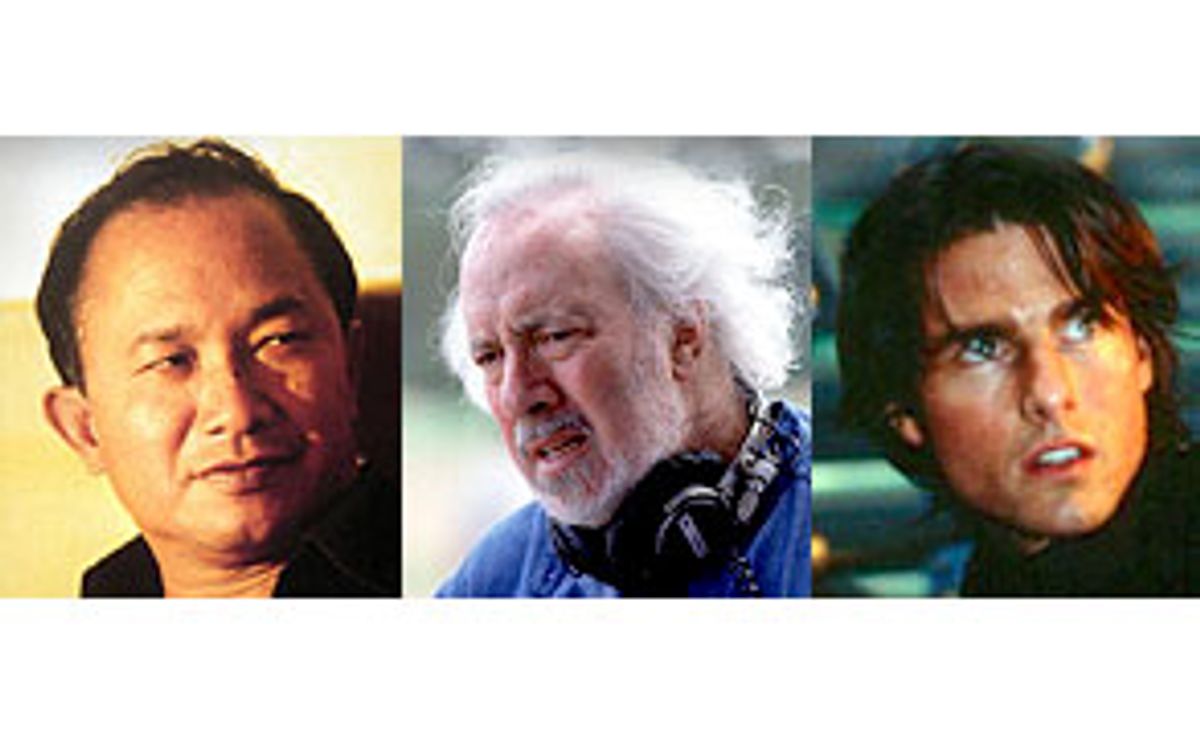

When he signed on to write this Tom Cruise super-production, Towne was no stranger to the series: Five years ago he won co-credit for the screenplay of the original by reworking the script scene by scene. But Towne came onto "Mission: Impossible 2" after a slew of other screenwriters (including William Goldman and Michael Tolkin) had failed to devise an acceptable screenplay -- and after the director, John Woo, had locked in a handful of splashy action set pieces.

"I don't have to tell you how great my trepidation was," Towne recalled the day before the film's opening. He remembered saying to Paula Wagner, who co-produced with Cruise: "My biggest fear is that I will write a script just good enough to make a really bad movie."

Luckily, he wrote a script that was good enough to make a really enjoyable movie, and earn him sole credit for the screenplay. It was Towne's idea to interlace a love duet with a quest to stop a killer virus. Another kind of biochemistry -- the kind that rages between Cruise as agent Ethan Hunt and the spellbinding Thandie Newton as an international jewel thief -- brings back those bygone days when Hollywood knew how to yoke together grit and glamour. The chases and shootouts benefit from the romantic sheen. And if director Woo's timing muffles the comedy and erotic playfulness, Towne himself is happy with the picture: "It does what it sets out to do: provide thrills, but with some feeling and sophistication."

Working on a probable blockbuster like "M:I-2" is the armchair screenwriter's equivalent of appearing on "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire." The characters are so much larger than life and the action so outlandish, at first you think it's as easy as jotting down a daydream. Then you realize how hard it is to place personalities and incidents in a narrative mesh that will engage an audience's emotions while a virtuoso action director like Woo is busy setting off cataclysmic explosions.

But Towne came to the task prepared. He has been an uncredited participant in many a Jerry Bruckheimer extravaganza (including the monster hit "Armageddon") and he's never lost touch with the popular pulse. His collaboration with Cruise, starting with his original screenplay for the misfiring "Days of Thunder," continued on "The Firm" (which Towne co-wrote), then the first "Mission: Impossible."

Towne has won a critical following for his work as a writer-director: "Personal Best" (1982) and "Without Limits" (1998). But he brings just as much commitment to collaborative tasks like "M:i-2." Interviewing him now was as full of revelations as it was when I interviewed him about "Chinatown" 27 years ago. The man breathes storytelling in all its forms; there's nothing strained or showoffy about his references. At one point he mentioned Katherine Anne Porter's short novel "Pale Horse, Pale Rider" as another work about a killer flu. Porter's heroine nearly dies from it, and she works in a couple of passages about the Kaiser spreading the flu ("It is really caused by germs brought by a German ship to Boston") that are right out of a movie like "M:I-2."

The outcome has been smooth, but the working out of this film was notoriously tough. Why?

There were a lot of writers on this movie before I came on. And at some point in that process John Woo came aboard. He had gotten very far with his action sequences. So finally, what they were left with were five or six highly developed action sequences and no story. So Tom [Cruise] and Paula [Wagner] said, "Guess what: These are the action sequences, please write the story." That was something I never had remotely attempted to do before. And it was an interesting exercise.

There were certain things that were not so difficult. Like the mountain-climbing sequence, which was originally planned for straightforward suspense. I said, "Well guys, you know, this is not 'Cliffhanger.' This should be our hero's idea of a busman's holiday. If we could, we should get Julie Andrews singing 'the hills are alive with the sound of music' or 'folderee, folderaa' -- I actually wrote that suggestion into the script! The point is he's having a good time.

And when I came on, in the opening sequence, in good "Mission Impossible" fashion, a guy was wearing a mask, and the mask was taken off, and what was revealed underneath was Dougray Scott. Well, who cares? Nobody would know who he is anyway.

You mean, the scientist we barely get to know was accompanied by a guy we don't know, who then took off his mask to reveal another guy we don't know?

That's exactly what I said.

I had seen a "60 Minutes" program in which drug companies were seen to peddle bad drugs to Third World countries, drugs they knew to be out of date or positively impotent. I thought this was a horribly immoral and frightening thing. I had mentioned this to Tom in passing and then he went his own way, since I was working on "Without Limits" and writing other projects. But he said, "That's interesting."

Do you remember reading about scientists who had been talking about the horrors of the old Spanish influenza in 1917, 1918? Katherine Anne Porter's "Pale Horse, Pale Rider" covered that. These scientists were saying that every 96 years or so there was likely to be another outbreak and we would be no more prepared now than they were then.

I read about a scientist in the '50s who tried to dig up from dead bodies some living remnant of tissue in order to make a vaccine of the old Spanish flu virus residing in that tissue. Finally in the '90s a couple of scientists went up to the frozen tundra in Alaska. They found a village where virtually all the inhabitants had been wiped out by that virus. They dug up the bodies from the tundra and found viable tissue with which they could make a vaccine -- and did. I thought this was kind of exciting, having nothing to do with any movie. It stimulated my thinking about drug companies and what they were doing. Drug companies are making less and less money because they have to make a broader variety of antibiotics because the simple sweeping antibiotics aren't as effective any more. What if they engineered both a killer virus and a vaccine to make money? From that came what you saw.

Did any of this get into the work done by the other writers?

Tom gave some of these ideas to somebody -- maybe to more than one writer. But he or they didn't really carry it to any length. The first four or five writers were making the movie something else. I think there were about seven writers in all -- it was an amazing number. I didn't read all their scripts -- basically, there was no point in it. What I was guided by were John's storyboards. I tried to work with John's stuff, and he tried to work with mine. For example, we made the car chase between Tom and Thandie a little less frenetic -- we pushed it toward courtship. John is actually a lovely man, and a gentle man.

The first two drafts were a nightmare, trying to back into the action sequences. But by the time I got to Australia and was working on the third draft, something happened. I remember 25 pages into it, I thought, I don't know where we're going to end up with this thing, but I suddenly felt the tingle that in its own way this script was beginning to be organic. I will tell you I never tried anything like this before. It was difficult.

Well, as you've written, "It's not Mission: Difficult -- it's 'Mission: Impossible!'"

There you go.

It must be satisfying to come up with a catch phrase that everyone will be saying for a couple of months.

It's so surprising: I didn't think that was going to happen. And I injected some chicken-shit misogynism into Anthony Hopkins' remarks, just to be politically incorrect. There's an interesting thing about audiences today: I guess that's one of the few ways to shock people. Cruise says Thandie doesn't have the training [to act as an agent and go back to her evil ex-lover, Scott], and Hopkins says, "She's a woman -- to go to bed with a man and lie to him, she has all the training she needs" and you hear, "Oh, oh my goodness! Wow!" Time was when you had to have a really scatological turn of phrase to get this kind of response.

I'm not particularly a John Woo fan. For me, this had enough else going for it so I could appreciate what he does and not let his mannerisms drive me nuts. Even the ludicrous introduction of his trademark doves in the climactic action scene actually works for the film, in a backdoor way, since it is an expression of personality -- of something beyond the hardware you usually get in these movies.

And Tom leavens certain things I usually don't like in martial arts movies -- and I almost realized that after the fact. When others wanted to cut out the mountain-climbing sequence, and the high dive from the helicopter, Tom and I went crazy, and I didn't know exactly why. But then I realized that for Tom, a "Mission: Impossible" movie is not about confronting some arch-villain or some enemy; it's about taking risks, it's about the joy of confrontation with self. That's ultimately what the mountain-climbing sequence is about.

Even when I was writing that line about how, instead of taking a ground route, his character, Ethan Hunt, "would rather engage in some acrobatic insanity," I didn't realize the overall implications -- that this is what distinguishes these movies from all the "Die Hard" films and things like that. It's about this kid who likes the fun of masks on and off and taking huge risks -- taking them himself.

He did those stunts himself. And I assure you, it's even more impressive than you may have heard. I remember being on the set at Bear Island one day, where the exchange is meant to take place between Brendan Gleeson [an avaricious drug-company executive] and Dougray Scott, and Tom said, "Man, I'm getting tired of doing that stunt," and I said to myself, "You know, for the money you're getting paid, you could probably do it." And then I saw the stunt: He runs dead at the camera, does a flip in the air unaided by CGI or wires or anything else, fires three blanks while he's upside-down at the camera and lands on his back. No CGI, no wires, just this kid. And he does this 20 times. I think the audience senses his sheer love of doing it -- I think the audience knows this thing is really happening.

A lot of Tom's appeal essentially hearkens back to an earlier form of American hero: Yankee ingenuity, "We didn't fire the first shot but we'll fire the last." The kind of blood-lust you got in the "Rambos" is not there. Instead, there's this other stuff, along with a sense of fairness, and I tried to arrange most of the violence that is visited on the villains so that they are hoisted on their own petard.

We once discussed how the classic Robin Hood was a great hero not because he was great at everything, but because he was great at how he interacted with a team. Does some of that enter into Ethan Hunt in the "Mission Impossible" movies?

Robin Hood was not necessarily more skilled or stronger than his band of merry men, but he recognized and appreciated their skills, and they followed him because he saw their worth. I always felt his skill as an archer was emblematic of his larger vision as a leader. This character is not the same, but in a strange way there is an element of that appreciation in his makeup. So if you're going to do these things in this increasingly Circus Maximus interactive atmosphere of movies, this is a better guy to focus on. And I can't help but respond to that. I'd rather have people identify with this guy than with someone dropping somebody off a cliff or any of the brutal stuff we see in other films.

You describe the series as being about the test of self. I know there's going to be a lot of debate going on about the differences in the two films because you have these two powerful directors, Brian De Palma and John Woo. But the consistent collaborators in both films are you and Cruise. And the second film refines devices from the first film; for example, those trick masks now serve as metaphors for a false self and a true self.

You see that in the con job on the Thandie Newton character, where I think most of the audience is kind of fooled.

You also take a leap there that's more typical of the first film: Alert viewers will feel that there's a bad jump because we've seen the guy who figures in that sequence just previously, in another setting. But this "jarring cut" is the preparation for the surprise.

Exactly. I like this film. I certainly had more of an opportunity to inject a storyline into it than I did in the first one, where the story was more set and I was working on more individual scenes. Here it was an ongoing collaboration with Tom and John. I think most people -- fairly overwhelmingly -- prefer this to the first film. The story is more follow-able and I think the story is fun.

And there are just dumb things that I like, like that moment of Dougray's when he says "I want you to try on some clothes" in that netherworld "Gatsby" way of his. When she slips out of what she's wearing, his eyes glaze over -- it gets a laugh in a good way in the audience, because the guy is so hopelessly enamored of her.

Both films have some surprising narrative experiments. In the first movie Jon Voight pins the blame for the massacre of his team on someone else; Cruise, out loud, reconstructs Voight's story; and the images show us what he really thinks -- that Voight is the villain. In the second film, in a long, crucial action sequence, the villain narrates what the good guy is doing.

This sequence serves a double purpose. It arouses anxiety on the part of the viewer, because you think, "Jesus Christ, he knows what's going to happen." It also informs the audience about the minimal technical stuff Cruise is doing, so as he's doing it they can say, "Ah yes, there's the injection gun." So it's an efficient sequence, and it's fun in terms of character, and hopefully it arouses, "Oh God, the villain is ahead of the hero."

I remember vividly working out, in the first "Mission: Impossible," the disparity between what one guy says happened, what really happened and what Tom is thinking, which I thought was a more radical thing than people realized or than people commented on. I thought that little mini-narrative was pretty good. And I worked out very specifically with Tom the sequence in this film, too.

Look. Here's a script that in its final form was 84 pages -- that tells you how efficient you have to be to advance the plot. For each page there's a minute and a half of screen time. John is filling the pages with action so you have to be super-efficient. In its own way it's no less complicated than the first story. I just think you can follow this one better.

It didn't take long before I thought of Hitchcock's "Notorious".

In a strange way you have both the villains in both those pictures deeply in love with the girl and you're meant to feel that. And I love that use of a triangle.

You even have a substitute for Claude Rains' protective, suspicious mother.

Yes, that Richard Roxburgh character. And we even have a racetrack! That was not intended; it's just suddenly we had this great racetrack down there. Sure there was an echo of "Notorious." It's very rare to develop a love triangle as a subplot that happily exists and helps you advance the plot -- that's a hard thing to do. But it also, not coincidentally, gives the heroine something to do for a change. Thandie Newton actually owns part of the story.

That for me was the source of the most fun -- she really is a spellbinder, and she gets something cooking with Cruise.

There's definitely a chemistry there. You know, Thandie was Nic's idea.

Nicole Kidman?

Yeah, Tom's wife suggested Thandie. I had seen "Flirting." But what I'd seen her in that really made me fall in love with her was her screen test for the island girl in "The Firm" [which Towne co-wrote]. I liked her so much better than anybody else I said to Sydney Pollack [the director] "Why don't you cast her?" And he said, "She's too cute, too attractive." And I didn't know quite what he meant by that unless he felt she would interfere with the leading lady.

So when Tom told me, "There's this actress, Thandie Newton," I said, "Don't even think about it -- that's a great idea. Please let's do it." I was so happy. She's such a bright girl and so much fun to talk to. She's quick, she's unaffected. The other thing I really like about her is that she's from an alien culture and there's not any hint of her having been affected by racism -- at least, no hint of it that I have ever seen. In "Flirting" she's like a little queen. She doesn't know about racism, doesn't care about it and that's invaluable for a romance like this one. There's no chip on her shoulder -- no expecting to have to lash back at somebody.

She's of a piece with Ingrid Bergman in "Saratoga Trunk"; that Casey Robinson screenplay where there's one of my favorite exchanges in movies. Bergman's kicking around the Latin Quarter in New Orleans and the guy asks, "Where will you go?" And she says, "What do you care?" And he says, "You'll pardon my saying so, but you're just an extraordinarily beautiful woman." And with that, she smiles suddenly and says, "Yes -- isn't it lucky."

In that spirit, Thandie is comfortable with her own attractiveness. Not in any vain, preening way -- just, "I'm there and I know I'm attractive: next case." And that's such an attractive quality. She's not being coy about it, and not being preoccupied with it.

Somebody took me to task for having Tom tell her, "Damn, you're beautiful." The interesting thing was the original interchange was "Damn, you're beautiful." Then she said, "That's because I'm on my back." Then he spun her around and said, "I don't think so." Those last two bits were lost because we didn't get them quite right. But I don't mind our fallback position, because she is so beautiful.

Speaking of "Notorious" -- her presence is part of what suggests other Cary Grant-Hitchcock movies too, like "To Catch a Thief" with Grace Kelly and "North By Northwest" with Eva Marie Saint.

Again, it's that regal feeling.

She's also a great silent actress.

I love that moment when Tom says, "Don't turn around," and the look on her face is, "You numb-nuts." And she turns around. I love it when she says, "What are you going to do? Spank me?" She's so expressive, she does a lot by doing so little.

You talked about the challenge of putting together a script from all these existing pieces. But I also was thinking these "Mission Impossible" films force you to do a kind of writing that's absolutely atypical for you. You're a writer who draws both from the movies and from reality -- what a character does for a living and where he or she grew up are matters that inform your dialogue. Here you may know what the characters do for a living, but it's either so insulated or fantastical it doesn't really give you any help.

Yeah, a lot of my tools go out the window. You're the only person who's hit on what was one of the central writing problems. That took some working at it: to develop a language that at least had the simulacra of life -- if that's what you want to call it -- even if it wasn't real. That's what takes three drafts: to get that feeling for language, to get the right level of reality -- or its own level.

I think it works. Like when you have the guys sort of tear apart a clichi -- we rolled a snowball into hell, now we'll see if it has a chance. It doesn't call attention to itself, but there's a low-key smartness to it.

And there is an occasional metaphor: "Suppose she is sort of a Trojan horse, why deny me the pleasure of a ride or two?" And the occasional archness of Hopkins, in his speech patterns, or when he talks about the pilot who didn't make the flight he was supposed to but made it on "to the next one, in cargo, stuffed into a rather small suitcase considering his size."

You were one of the great advocates of the American way of swearing in movies like "The Last Detail" and "Shampoo," but here the language is restrained.

That was part of seeking the right tone. When we started to use real language in real situations in the '70s, with the new freedom, it got so abused: In science fiction movies people were swearing. So the coin is debased. I remember as a kid seeing "From Here to Eternity" and thinking, "God, they don't really swear like they do in the military." And then I remember seeing the movie years later and thinking how real it seemed because they didn't swear. Your perceptions change. I think Pauline Kael observed once, as she did so many things: The breaking of one clichi invariably leads to the establishment of another, so you have to break it all over again.

I thought "M:I-2" opened up more possibilities for the series than the other one did; the Hopkins character, for example, is even more inscrutable and harsh than agency chiefs usually are in movies like this.

I had always worried that "Mission" movies would always be over-involved in process and in the technological version of the Feydeau farce, with people pulling those masks on and off. But here I think we managed to use those things as metaphors for character. Part of it is that working with Tom really is a joy. There is no telling what this kid will do: He's getting better and better, and he's sharp. The truth of the matter is he's indecently decent. You think, "Oh shit -- all this and decency too? He is the only guy in his position, who, when he hires you, it's always about, as much as men can gauge such things, what somebody's worth, not what he can be gotten for. That's unusual.

One of the other not incidental benefits of working with that guy is: If you can think it, and if you can talk him into it, it's between the two of you, or in this case, among the three of us, because John, though not very talkative, reacted very strongly when he liked things, and would push them. But as far as the studio goes -- the memos from all the mini-executives are something I never had to see or know anything about. They were the first to admit that they said we'd never get away with the last mask we use, and in fact audiences adore it.

And the masks are better in this digitally advanced age.

They do work much better. I love that moment where his face seems to go slack in just the right way after he's shot and you can begin to see the transformation.

I liked Brendan Gleeson so much as the drug exec I wanted to see more of him. After "The General," it was nice to see him looking relatively trim in a business suit.

We had more of him but what you saw in the final film was all the story would accommodate -- we did give him that aria about the difficulty of making money in the world of boutique antibiotics.

How involved was Woo in the story development?

He was involved every day in what we did; it's just, for the moment-to-moment work, his language skills are not such that he was able to achieve it. We would read to him and refer to him and he would make suggestions. But the actual involvement, in terms of the interplay, was with Tom and me. At the end of every day in Australia, Tom was there. And sometimes he would go up to [producer] Paula [Wagner's] room while I was writing; then he'd come down, take the pages, run back up the fire escape, and, I was told later, read the pages to whoever would listen to him and come back down.

That last mask: He was going to Stanley [Kubrick's] funeral -- he called me from the plane and said we need a new twist at the end; we need some kind of mask thing. I asked, "Can we go to the well one more time?" He said, "Absolutely." I said, "OK, give me a half hour." So I mentioned it to Paula and my wife and they said "You'll never get away with another one." And I said, "OK, but what if I do this?" And their reaction was: You can get away with that. And Tom called back on the phone from the plane and that was that.

Tom is increasingly fun to work with -- there's tremendous growth. And he doesn't refer to anything that's not out of his own gut. He doesn't have anyone else bending his ear. It's what he thinks on the spot.

Were there things you might have done with just a little more breathing space between the big action sequences? A little more with Tom and Thandie, perhaps?

Probably, yeah. There were more scenes with her, but it's tough. The whole thing starts moving at a certain pace, and you kind of sense that if you go slower than that, if you digress, if your character stuff just slows things down too much, what it really affects is not the audience getting bored, but the level of reality. It's like an act of prestidigitation -- you've just got to sort of keep it going, or it seems less real, and you become aware of the artifice.

Thinking back on even the most classic and universally loved of these romantic adventure-cum-suspense movies, they're always team efforts -- whether we're talking about Hitchcock and screenwriter Ben Hecht on "Notorious" or Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehman on "North By Northwest."

Yes, and you have to have that teamwork -- you have to work with people so immersed in this world that they can give reality to the romance and adventure and suspense, or else it's all a lighter-than-air fairy tale. You have to ground it -- and to do that you have to help each other believe in it.

Shares