Researchers from all over the globe descended on Durban, South Africa, last week for the 13th International AIDS Conference, and yet one of the most hopeful results in AIDS treatment today was not presented: the Philadelphia patient.

He is a chronic AIDS sufferer who, as part of a groundbreaking study, took a drug holiday from his medication. Then he stopped taking drugs completely and, for more than three months, had very low levels of HIV in his blood. This is significant, though not unique: A handful of cases in the past year has shown that structured drug holidays may not just be benign, but also helpful in fighting HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

What distinguishes the Philadelphia patient, along with four patients from a Barcelona study, is that they demonstrate how drug holidays can trigger the immune responses in chronic patients -- enough to fight, and control, HIV. (At least for a while.) Other scientists have assumed this but not shown it conclusively.

The idea that patients can suspend taking drugs for periods of time is one of the hottest topics in treatment research today. Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), says: "We're seeing a groundswell of interest in this kind of research, and we've encouraged the scientists associated with our grant money to get involved. A scientist who submits a treatment-interruption proposal to us will very likely get funding." In fact, many of the country's major AIDS researchers are getting into the field, and it dominated the headlines out of Durban.

This is especially notable since until two years ago such research was practically forbidden for fear that after drug vacations, a reemerging HIV would mutate into drug-resistant forms. But those worries have now been partially allayed, as there has been only a single anecdotal case of this occurring. "We would not be doing this so aggressively if our back weren't to the wall. We're running out of therapeutic options for patients," says Dr. Lawrence Fox, the NIAID medical officer in charge of clinical research efforts.

Certainly there's a real urgency to find alternatives to the often toxic and always expensive "drug cocktails" of protease inhibitors and older drugs like AZT, to which many patients develop resistance. Four years ago, the world renown AIDS researcher David Ho landed on the cover of Time magazine for discovering the cocktail approach and it certainly has prolonged countless lives. But enthusiasm has worn off with a treatment that costs upwards of $15,000 a year and involves on average 24 pills day. Scientists now agree -- especially those with an eye turned on the millions of poverty-stricken AIDS sufferers in Africa -- that a lifelong dependence on such a high-priced cocktail is simply not a viable strategy. "The drugs are damn toxic, and we're saying, let's figure out how to take a drug holiday but in a structured way," says Fox.

The first, modest hope of supervised drug vacations (or structured treatment interruption, STI, as the therapy is known), is that patients could at least temporarily be spared the expense and nasty side effects during their holidays -- without jeopardizing their ability to fight HIV upon resuming treatment. Fauci gave a much-noted talk at Durban in which he touted STI and cited his own recent study of nine patients who took several month-long drug vacations without any ill effects. Fauci very cautiously concluded that patients might be able to spend 30 to 50 percent of their lives off medication, although his data are very preliminary. He repeatedly stressed that by no means should patients take themselves off drugs, since the data don't yet support it.

A second, more exciting hope for supervised drug vacations is that they could actually boost the immune system's response to HIV. A few studies have found that STI leads to sizeable and sustained declines in HIV levels in some patients. The theory is that when treatment is suspended and HIV slowly creeps back, the immune system also rouses itself -- now able to fight the lower level of virus. Before HIV can return too forcefully and wipe out the fledgling immune response, however, the patient goes back on drug treatment. The immune improvement is preserved, and, during the next treatment interruption, is ratcheted up ever so slightly. It's thought this cycle can repeat itself until the immune system is strong enough to suppress the virus for months, perhaps longer. The virus never goes away completely, but patients may build up enough of an immune response to keep it at bay.

A handful of studies, including Fauci's, suggest this reaction is possible. However, studies that are further along, as are those involving the Philadelphia and Barcelona patients, show that this process actually can work.

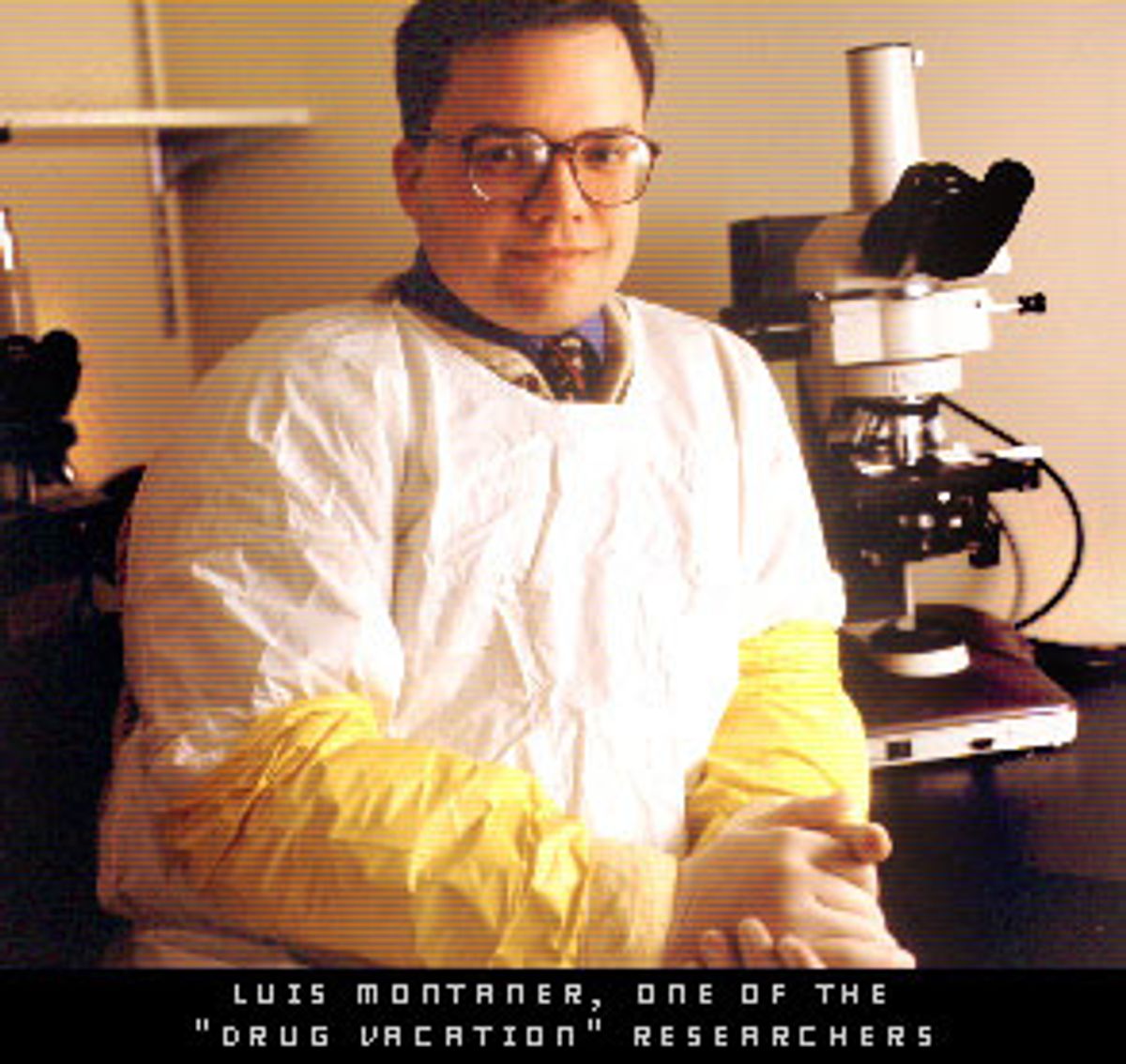

The Philadelphia patient study is the first one that will be published, in the September issue of the Journal of Infectious Diseases. Dr. Luis Montaner, a University of Pennsylvania assistant professor and head of HIV research at Philadelphia's Wistar Institute, recruited 10 AIDS patients from Philadelphia FIGHT, a community-based organization that caters to minorities with HIV. Five of the participants agreed to be monitored while, at their own discretion, they interrupted their medication for a median period of eight weeks; the five control patients were not on any medication. (Though Montaner sought to do structured treatment interruptions, he was stymied by a federally mandated institutional review board, which, at the time, thought that structured interruptions were too dangerous.)

All five experimental patients showed significant increases in anti-HIV immune response during the interruption periods. This result provided an observational basis for believing that structured treatment interruptions might allow HIV-positive individuals to boost their immune response over the long term.

The standout in Montaner's original experiment was patient C-13, the Philadelphia patient. A Caucasian man in his 40s, he was diagnosed with HIV in 1987 and had been on a drug cocktail, including 3tc, d4t and viracept, for three years before entering Montaner's study. After re-initiating medication for two months, he decided to stop -- permanently. In the months that followed, his immune system responded even more powerfully against the HIV virus. This led Montaner to conceive of a new experiment -- this time with structured treatment interruptions, which only in the past few months have gained enough credibility in the U.S. to pass ethical review boards.

At the time, few believed it possible to jump-start the immune systems of chronic patients -- namely, the 99 percent of HIV positive patients who have lived with the virus for some time. Subsequent research dealt with the more hopeful groups of acute patients who are diagnosed and treated soon after being infected. But no one thought an immune system that had been ravaged over time could recover.

Montaner was optimistic, however-- in part because early on, in meetings with HIV-positive patients, he had heard stories of the drug holidays they sometimes took without too many problems. This piqued his curiosity.

Montaner also knew about two important papers. One, by Bruce Walker, published in Science in November 1997, showed that, contrary to accepted dogma of the time, HIV did not wipe out every trace of immune cells that could fight the virus. In fact, smaller studies showed that a subset of infected people -- the so-called "long-term nonprogressors" who were disease-free for years -- had high levels of an important white blood T-cell trained specifically to kill HIV. These T-cells are sometimes called helper cells because they're like little generals who rally the rest of the immune system into action. They're an essential starting point to fight any virus.

Another important study, by Brigette Autran, which ran in Science in July 1997, showed that patients on the drug cocktail were recovering helper T-cells trained to kill flu and other viruses, but not HIV.

But why did some helper T-cells flourish and return but not those against HIV? "I thought maybe the reason was that in order to stimulate the T-cells to grow up and fight HIV, they needed some HIV to react against," Montaner says. "In late 1997, the evidence suggested that drugs wiped out HIV's capacity to replicate. So I thought that maybe, if a patient went off drugs, you could let HIV rebound just enough to stimulate the production of anti-HIV helper cells." Montaner wrote up the idea in early 1998, got funding and started working that fall.

That same summer, aids researchers everywhere were stunned by news of a Berlin man who had terminated drug therapy yet showed almost no detectable HIV for almost 18 months. This "Berlin patient" also had an unusual number of helper cells, so researchers wondered if his drug holiday could somehow be the cause. But it's difficult to say what happened in the Berlin patient's case since he was not in a controlled study, and it is not known whether or not he had a weak virus to start, or if the drug holiday actually did boost his immune system.

Nevertheless, this idea of auto-vaccination through treatment interruption intrigued researchers, and they started to devise experiments. Dr. Jose M. Gatell, associate professor at the University of Barcelona, started his rival study at this time. And Montaner struggled to keep up. His budget, made up from a patchwork of grants, amounted to only $135,000. Fifty thousand of it comes from an octogenarian lady in a retirement community whom Montaner visits regularly for three-hour lunches to report on his progress.

Even so, Montaner's study will be the first published account of a chronic patient whose immune system came back to life enough to effectively suppress HIV. It will also be the first published study to show that during treatment interruptions, the returning HIV stimulates anti-HIV immune cells (CD4 and CD8) to work together.

If true, Dr. Franco Lori, a prominent AIDS researcher in Italy, said, Montaner's research would be "quite significant and encouraging." But he, along with several other leading researchers contacted, declined to comment on Montaner's study until they see the full results.

Of course, there are still doubts about STI, mainly concerns that taking people on and off drugs will spur the creation of drug-resistant viruses. After the Durban conference, policymakers will increasingly target how STI could help the poor, who can't afford the drug cocktail, much less the kind of sophisticated blood monitoring that STI demands. A small consolation is that Lori is developing a simpler assay that even relatively primitive labs could use. And in developed nations, "treatment interruption would be great news, and people would very quickly move to this model," says Fox.

The next generation of studies on chronic patients will be bigger and better controlled. Other than the two NIH ones (with 80 and 480 patients, respectively), Gatell is collaborating with a Swiss team on a 120-person study; Lori is doing one with 50 patients; Fauci will increase the number his patients to 70; and there will be others. In many of these studies, patients go through a uniform regimen -- patients are taken on and off drugs at the same time for the same number of weeks. The advantage of this approach is that it might lead relatively quickly to a regime that could be widely applied. It's a blunt instrument, however. A more nuanced approach is being pursued by several other researchers, including Montaner. In his next study, he will create individualized treatment programs for his AIDS patients, albeit with some general guidelines. Although the "off" periods will be the same for all patients (first two, then four, then six, and finally 10+ weeks, to gradually build up immune response), the "on" periods will vary. A patient will only go off treatment again when his HIV level stays low for at least two weeks.

What all researchers agree upon most is that no one should read these studies and conclude that they sanction random drug holidays. Fox says he was horrified at Durban last week when a doctor from Thailand came up and said he thought Thailand could save a lot of money be doing treatment interruption in the near future. It's still much too early to jump to such conclusions, but it is promising enough to have hope.

Shares