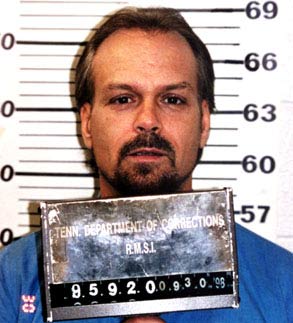

Philip Workman seemed to know.

Last week the Tennessee death row inmate picked up a pay phone at Nashville’s Riverbend Maximum Security Prison and dialed his defense attorneys of nearly a decade. Christopher Minton and Jefferson Dorsey had received word only moments before that the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals had rendered its decision not to grant Workman a new trial.

The decision came unexpectedly. It had been five months since the defense team was granted the rare en banc — meaning “entire bench” — to evaluate new ballistics evidence and an affidavit stating that a key eyewitness had lied on the stand more than 20 years ago when he testified that he saw Workman shoot and kill a Memphis police officer during a fast-food restaurant robbery.

In silence, Workman listened to Dorsey tell him that the 14-member panel of judges had split their votes — directly down party lines. Seven nominated by Democratic presidents had voted to rehear his case; seven Republican nominated judges voted to lift his stay. An en banc tie is extremely rare.

But according to the law, the tie vote means the 6th Circuit must allow a subordinate court’s denial of appeal to stand. The tie is both a shock and disappointment to the defense. Although seven federal judges believe Workman’s conviction is full of holes, especially since they viewed an X-ray discovered by the defense in February that casts doubt on whether Workman’s gun was the murder weapon, Workman’s stay has been lifted. After 17 years on death row, he is likely to be the second prisoner lethally injected in Tennessee since 1960.

The execution could heat up the presidential race. A former Tennessee senator whose campaign is based in Nashville, Al Gore has been loath to talk much about his position on the death penalty. His official Web site states that he is for the penalty, and his record supports that. Last year, he refused to lend his name to a Senate effort that would allow inmates to submit DNA that might prove their innocence.

David Mason, chairman of the political science department at the University of Memphis, says Workman’s case might make it more difficult for Gore to point a sanctimonious finger at opponent George W. Bush for the Texas governor’s record of executions.

“But being the acting governor of a state and thus wielding direct power to grant clemency is different than being a senator or being vice president,” says Mason. “It’s fair to be more critical of Bush. I don’t know of any case where a vice president has stepped in to influence a governor, especially when you consider Gore is a Democrat and Tennessee’s governor is a Republican.”

Five media spokespeople in the Gore campaign had no knowledge of the case at all, including Gore’s main spokesperson in Nashville, Jano Cabrern, who would only say, “Gore supports the death penalty for heinous crimes and thinks that the American people agree with him.”

Workman’s execution will be scheduled this week, just as fresh doubts are emerging about the death penalty’s fairness. On Tuesday, the Justice Department issued a survey finding wide disparities in the way death sentences are implemented. As a white man, Workman does not fit the profile of those capital convicts disproportionately sentenced to death — about 80 percent are minorities. But as a poor, drug-addicted man convicted in one of the federal districts in which the death penalty is most often recommended by prosecutors, Workman is a prime example of the way class and geography figure into justice.

That is little consolation to Workman’s defense team, which now has two options. It can appeal to the Supreme Court. But the chances of the highest court accepting the case are slim because it usually decides issues of legality, not guilt or innocence. Clemency from Tennessee Gov. Don Sundquist is unlikely. Sundquist will not comment about the case, but he, too, says he “believes in the death penalty for heinous crimes,” and that he will “weigh every case on its own merits.”

Dorsey has explained those choices to Workman.

“Philip is a very strong person, very businesslike and never hopeless,” says Dorsey. “He wants to know what our next move is.”

Dorsey had been quoted in the press as saying Workman was “stunned and upset.”

“I’m the one who’s stunned and upset,” Dorsey explains. “I know what our options are and they aren’t very good. Frankly, I’m feeling a sense of doom.”

Within hours of the 6th Circuit’s ruling, Tennessee Attorney General Paul Summers filed a request with the state supreme court to set an execution date. The defense has 10 days, ending Friday, to reply. A vocal opponent of commuting Workman’s sentence, Summers once told reporters that it didn’t matter if the bullet from Workman’s .45 killed Lt. Ronald Oliver while the two struggled outside a Memphis Wendy’s restaurant during a robbery Workman admits he committed. Workman is “morally responsible,” Summers said.

“It’s tragic that we are not just trying to prove through legal means that there is reasonable doubt that Philip didn’t kill Oliver,” says Dorsey. “There are a lot of people who want vengeance for the death of a cop.”

Partisan politics appear to have played a role in the rare tie vote on this case. Until a month ago, there were 12 judges, not 14, sitting on the 6th Circuit’s en banc panel. At the time, it looked as if the majority would vote in favor of granting Workman a new trial. But at the last minute, two senior, or retired, judges — both appointed by Republicans — decided that they wanted to be part of the panel. Senior judges have the right to join deliberations when they choose.

Those same judges also happened to be on the three-judge panel that had already denied Workman’s request for a new trial. The senior Republican judges swung the en banc vote to a tie. The circuit court’s 11-page dissenting opinion, written by one of those judges, dismisses the importance of the X-ray, which was in the county coroner’s possession for 17 years until February, when the defense noticed mention of it in a buried court document.

The X-ray shows that the bullet that killed Oliver did not fragment inside his body. This is significant because it most likely was not a .45 bullet — the kind of ammunition Workman’s gun used. The non-fragmentation suggests that the bullet might have come from a .38 special, the kind of bullet two other police officers at the scene of the robbery carried in their firearms. The judge, however, wrote that the X-ray proves “nothing that the original autopsy and photographs” did not show. He contends that the X-ray is less telling than the wounds on Oliver’s body, which could have been caused by a .45.

Nor were the judges swayed by the emotional testimony of eyewitness Harold Davis, who now says he perjured himself during Workman’s original trial. The defense spent years trying to track down the vagabond alcoholic, who took the stand in 1982 and dramatically told of how he saw Workman cold-bloodedly point his .45 at Oliver and fire. Davis changed his story after the trial, saying that he was in his truck across the street from the Wendy’s restaurant and only saw an altercation between Oliver and Workman from his rearview mirror. In 1999 the defense finally tracked Davis down in a Phoenix motel room. He tearfully confessed on videotape that he saw nothing, but was bullied by members of the Memphis Police Department to testify otherwise. Yet because Davis’ recantation was not taken under oath, the dissenting judges will not consider it.

The seven judges who believe Workman’s case deserves a new trial are not alone. Seven of the original eight jurors who condemned Workman now say they doubt he shot Oliver. Five of them have signed sworn statements that they would decided the case differently had they known then what has come to light today. But it is Paula Dodillet, Oliver’s daughter, who has attracted national attention for joining those jurors in their pleas for granting Workman clemency.

The defense has long held to a theory that friendly fire killed Oliver, that in the tussle and confusion that night, a fellow officer’s gun went off, firing the fatal shot. The dissenting judges note in their opinion that the defense has no proof of that.

But Tennessee’s public support for the death penalty tips the scales toward another kind of certainty. In Tennessee, it seems that supporting a reexamination of the death penalty is politically dangerous. Gore has avoided such discussion, despite widespread criticism of Bush’s role in executing killers under similar circumstances of judicial doubt.

Locally, Nashville U.S. District Judge John Nixon is considered a controversial character, often criticized for his constant reluctance to impose the death penalty. Only once has Nixon ruled in favor of the death penalty — for child killer Robert Glen Coe, whose case prompted legislators to reinstitute the penalty a decade ago. In April, Coe was Tennessee’s first prisoner to be lethally injected since 1960.

The grisly details of Coe’s case contributed to a resurgence of public support for the death penalty. A statewide Knoxville News-Sentinel poll taken two months after Coe’s execution showed that 61 percent of Tennesseans favor the death penalty. Such public sentiment has pushed politicians from tacit philosophical agreement to more concrete support.

Dorsey says his client’s situation is “like being stuck in the middle of a nightmare.” If Workman is executed, it will be the lawyer’s first experience watching a client die. But Dorsey adamantly says that there will never be a point of utter hopelessness. As with Coe — who ate his final meal four times as various state judges issued stays for weeks to reexamine his case — Workman could be similarly yo-yoed in and out of Riverbend Prison’s death watch.

“Until Philip is strapped to that bed, there’s always something that can be done,” says Dorsey. “Fear is the issue here: the what if. But I am not totally despondent about the system. I think it’s often unfair, but I believe in it enough to be a part of it.”