My parents always kept a small plot of land in the backyard as a garden. It was roughly the size of an average bedroom. Pretty small. But they hovered around that garden all spring and summer. They plowed, fertilized, hoed, mulched, and sampled the soil. They watered. They pinched leaves. At night they pointed to pictures in books and seed magazines, which eventually accumulated and took over the dining room.

And then, a few months later, there was a crop of something. Usually a crop of mutant something. One year it was zucchini. Thousands of zucchini crawled out of the garden as if cast in a late-night horror film. Neighbors came home to anonymous zucchini breads, pies, and cakes delicately balanced inside of screen doors or stuffed into mailboxes. Dad kept a huge zucchini next to his bed in case there were intruders.

I was diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease in April, the planting month. Dr. Brodsky talked with his arms crossed in front of him, listing the chemotherapy agents I would be taking and their side effects. Prednisone. Procarbazine. Nitrogen mustard. Vincristine. The latter two would cause nausea and vomiting. It sounded unpleasant.

A few nights before I was scheduled to start treatment, I called a friend, the only person my age I knew who'd had cancer. He muttered five gruff words into the phone: "Chemo's grim, man, get weed."

I trotted into the living room and nonchalantly announced to the family that I was going to buy marijuana to help with the nausea and vomiting.

There was an oppressive silence, punctuated only by the rapid tapping of my mother's finger on an armchair. Then she began, her voice carrying that staccato edge she generally reserved for my father. She told me in no uncertain terms that there would be no drugs in the house. She berated me about the dangers of illicit substances, the horrors that visit lives filled with addiction, and swore to me that her roof would never shelter a drug user. She ended her diatribe with an outstretched finger.

With the vigor of an adolescent with a cause, I argued back that for me, marijuana would be medicine, the only medicine that could temper the violent treatment I faced. That it wasn't addictive, and that my body would soon process toxins far more dangerous than marijuana. At the end of our conversation we were where we began. I knew my mother. Once she was entrenched in a position, argument was futile. I retreated.

I still wonder what happened to her during the night. Maybe she studied the pamphlets the doctors provided, maybe she woke up in a sweat, the remnants of noxious dreams about her son and chemotherapy still etched in her mind's eye. I don't know. But I do know this. The next morning my mother ran her finger down the "Smoke Shop" listings in the phone book. She called a number of establishments, asking detailed questions and jotting down words like bong, carb, and water pipe. Then she gathered her keys and purse, and 30 minutes later was walking down the aisles of a head shop called Stairway to Heaven, taking notes and carefully checking the merchandise for shoddy workmanship. My mother is a Consumer Reports shopper.

I was sitting on the ground in the backyard when my mother's car pulled into the driveway. A few moments later she appeared on the back porch waving a three-foot bong over her head. She proclaimed her find with the same robust voice she'd used for years to call my brother and me to dinner: "Is this one okay? They didn't have blue ... "

When I entered the house she delicatelv handed me the bong and some money. She brushed dust from my shoulder and softly told me to do whatever I needed to get the marijuana. After a quick phone call I left to make my purchase. When I returned with the small Baggie my mother asked to see it. I felt a sharp adolescent fear, conditioned from years of living under my mother's vigilant eyes. I handed it over. She looked into the small bag. Incredulous.

"Where's the rest of it?" she asked.

"That's it, Ma," I said. She squinted at me. "I swear, Ma. That's it."

She murmured quietly, "Honey, give me the seeds."

I thought of huge zucchinis.

When my father learned of my mother's plan he clipped two articles out of the paper with the titles "Police Raid Yields Results" and "Drug House Seized." He put them under a magnet on the refrigerator and underlined the worst parts. That night, as we prepared for dinner, Mom read them, nodded soberly, and said, "Bring them on."

That summer my parents plowed, fertilized, hoed, mulched, and sampled the soil. They watered. They pinched leaves. And that August the mutant crop arrived. Ten bushy plants grew over 11 feet tall in our backyard, eclipsing the sunflowers in front of them. Far more weed than I could have smoked in a lifetime.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The Gainesville airport is small. It doesn't even have a tower. There are two gates and you can see both from the airport lobby. It's a humid night, the air heavy with sweat and the occasional mosquito. Gainesville is a college town and the airport is filled with college wear. There are a lot of baseball caps, ponytails, and shorts. People sit reading or watching tiny televisions built into kiosks scattered through the lobby.

Football is on television. I'm watching the second half of a depressing Patriots game when I see their plane coast down outside the windows. I stand up with the others and we gather around the gate. Then, a little while later, I feel a familiar comfort as I spot my father's bobbing bald head. And then Mom. That confident stride I'd know anywhere. Her purse strap runs across her body like a crossing guard's reflector and for a moment she looks as if she's in uniform. Before I realize it I'm cutting through the small crowd and into their arms. Both of them at once. Big tired smiles. My cheeks feel hot.

We stand quietly at the baggage conveyor. A few bags arrive and we pull them off the belt. Then more. And more. Mom has never been an efficient packer. It's more important to be prepared for any eventuality than to be able to fit one's luggage into a standard-sized vehicle like, say, a U-Haul. The sixth bag arrives. It's roughly the size of a Buick.

"Jimmy Hoffa's body is in there?" my father suggests.

"Don't be a wise-ass," my mother says. I grunt under the weight.

The inquisition starts on the drive. My parents haven't been to Gainesville before. Or our new apartment. Is there any place to get good bagels in this town? Is the biopsy still scheduled for Thursday morning? How long will I be in the hospital? Since I haven't had any other symptoms, couldn't it just be a cyst or something? I look tired -- have I been going to classes? Do I want my father to drive? Maybe I shouldn't have carried the bags? How's graduate school, is it harder than Vassar?

Dad and I lug the baggage into our new apartment. We carry in the Jimmy Hoffa bag together. When we finally manage to get it in, we are both laughing at its weight. Indignant, Mom directs us to drop it in the kitchen.

"It's hot," Mom says, working the knob on the air conditioner. "Maybe we can go to Payne's Prairie or Ginnie Springs tomorrow, before you meet with the physicians?" she asks. My parents always do this. No matter where I am, they know more about the place than I do. Where every historical site is, how many Apaches were relocated there in the 1880s, and, of course, where they might find a red-bellied plover. Payne's Prairie is a large swamp south of Gainesville. At the time, I hadn't heard of it. Or Ginnie Springs, where, according to my mother, crystal-clear blue water rises out of the limestone.

There's knocking and the front door swings open. "I want you to finally meet Terry," I say. Mom stops fiddling with the air conditioner and stares. Terry walks in. She is all smiles. There are warm introductions. We chat for a few minutes and then I go to my new hall closet to find towels, leaving Terry and my parents alone in the kitchen. I'm digging through bath towels when I hear Terry, her voice much louder than usual.

"OH MY GOD, is that what I THINK it is?"

"What?" I hear my mother say softly.

"Oh my God. OH MY GOD! DANIEL!" Terry yells.

What's wrong? I walk briskly back to the room, matching washcloths in my arms. I arrive in time to see my mother yank, and finally free, a massive, plastic Ziploc baggy from the Hoffa bag.

I know immediately that I have never seen this much marijuana crammed into such a small space. It must weigh a pound. The corners of the bag are splayed out and soon it's going to give birth to its contents.

Terry asks softly, "You didn't check that through ..." She looks from my mother to me and then to my father.

"No one searched my bag," Mom says, flat. Then she sets the marijuana down in the middle of the kitchen table and walks over to the stove. She lifts my teapot and begins to fill it with water.

"We've got plenty more hanging in the attic if you need it. So, Terry ... have you been to Ginnie Springs?"

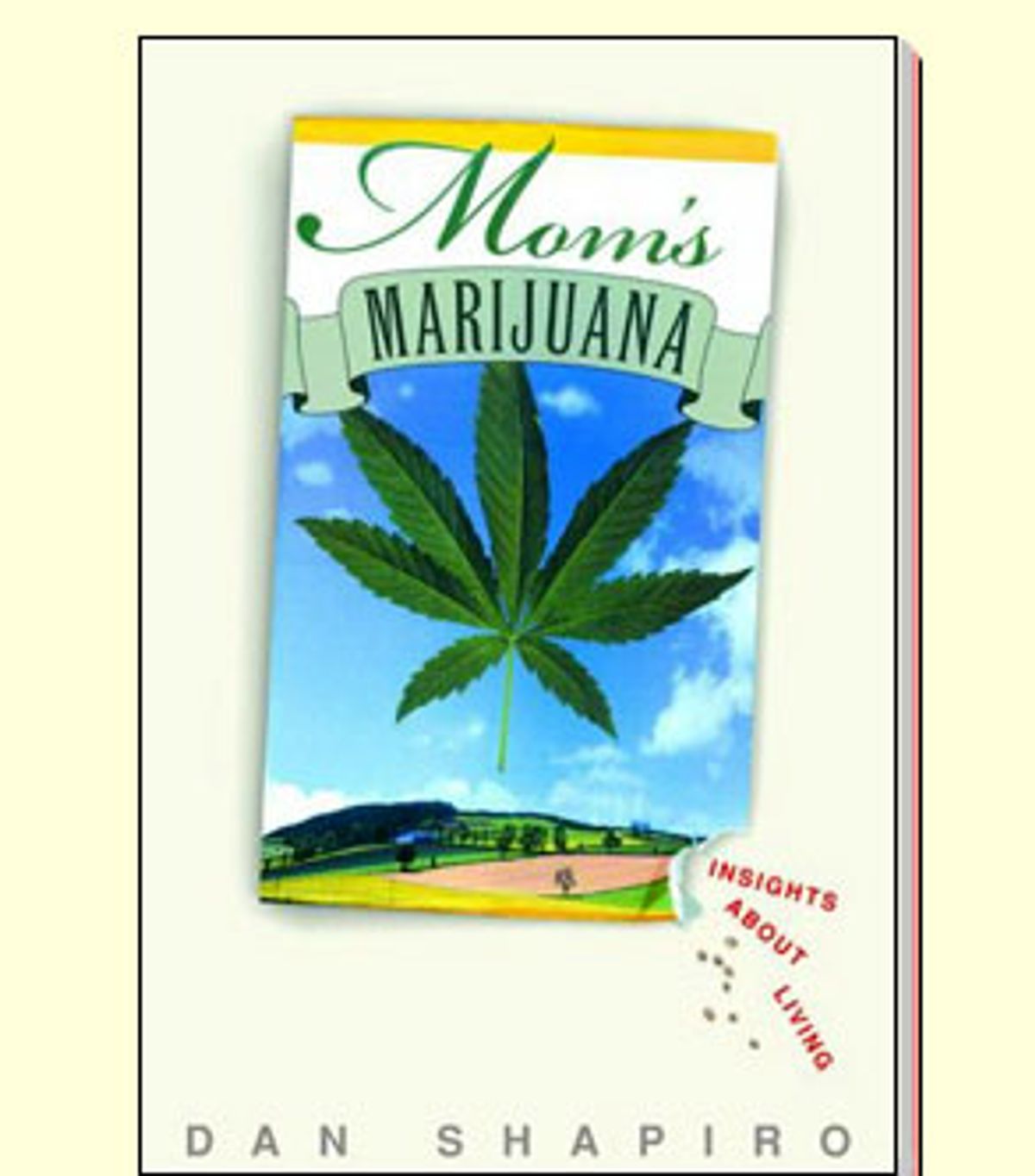

Shares