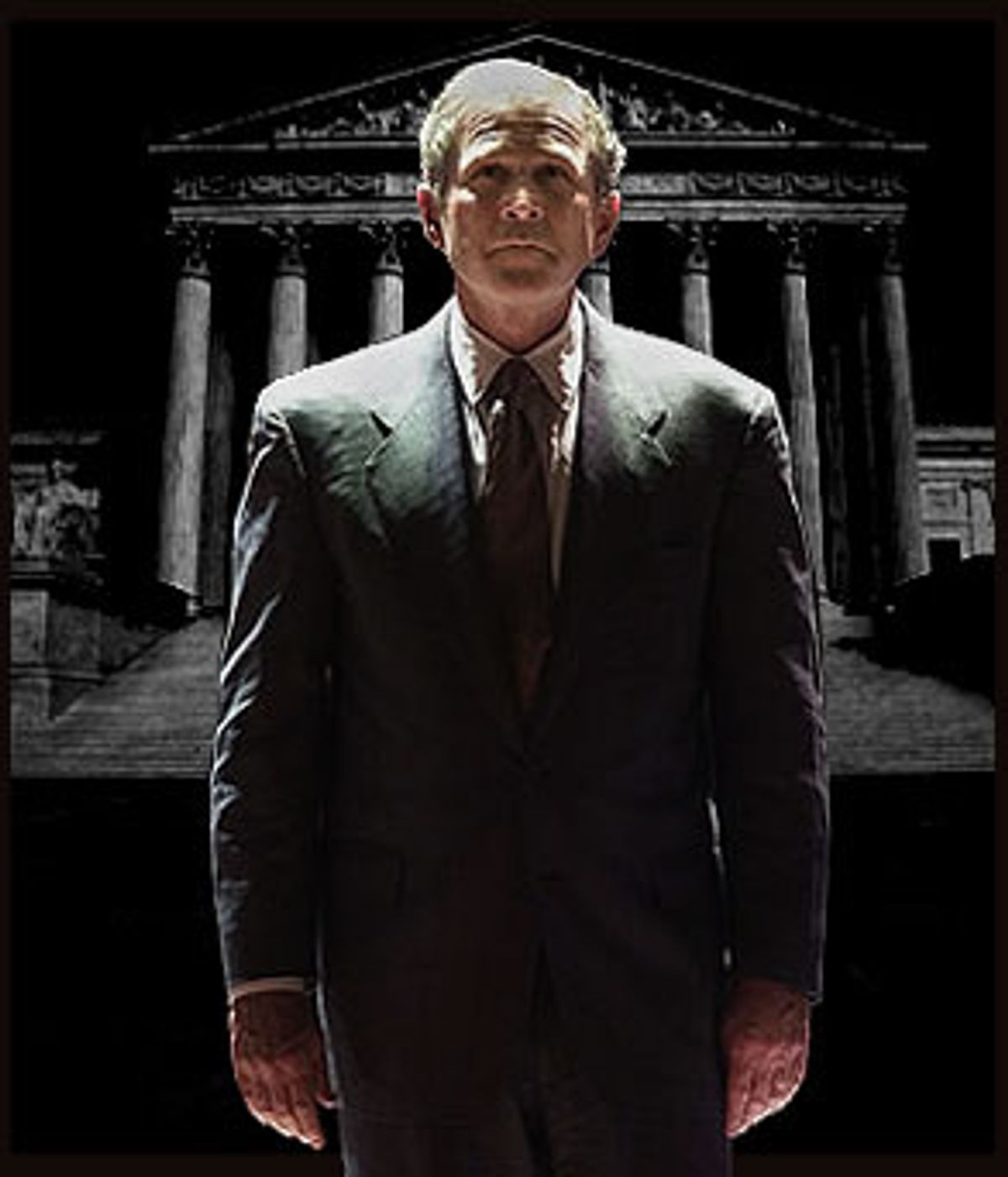

Tuesday, Dec. 12, is a day that will live in American infamy long after the tainted election of George W. Bush has faded from memory. With their rash, divisive decision to dispense with the risky and inconvenient workings of democracy and simply award the presidency to their fellow Republican, five right-wing justices dragged the Supreme Court down to perhaps its most ignominious point since the Dred Scott decision.

The court was the last American civic institution to have preserved an aura of impartiality, to be regarded as above the gutter of partisanship and self-interest. The reality, of course, is that no court, no judge, no human being, is completely free of those entanglements. Yet the court has generally acted wisely in avoiding judgments that would inevitably and utterly besmirch it. With one reckless and partisan ruling, it squandered its most precious possession: its reputation. It may take years, even decades, to repair the damage done by the Scalia-Rehnquist court's decision to cancel the election and crown the winner.

It's hard not to conclude, now that this whole sorry saga is over, that the fix was in from the beginning. Not the crude, "vast right-wing conspiracy" fix of Hillary Clinton's imagination, but a de facto fix. Why shouldn't one think the game was rigged, when five Republican-appointed justices -- one of whose son works for the law firm of the lawyer representing Bush, another of whose wife is recruiting staff for the Bush admininstration and two of whom have made clear their desire to retire under a Republican administration -- trashed their entire judicial philosophy to ram through, with only the most cramped of legal justifications, a last-second victory for a Republican who lost the national popular vote and, when the votes in Florida are actually counted, is likely to have lost the Florida one as well?

Perfect justice does not exist. But this was judicial folly, politically explosive and judicially threadbare. This was the court stepping in and awarding victory to one side before the game was over. Even those of us who don't often agree with the court's conservative majority expected better.

As Justice Stevens wrote in his savage dissent, "The position by the majority of this court can only lend credence to the most cynical appraisal of the work of judges throughout the land ... Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year's election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the nation's confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law."

As soon as the ruling was handed down, a nearly hysterical chorus of TV commentators, many of them cynical bear-baiters who wouldn't believe oaths sworn by their own mothers, suddenly pulled long faces and began urging the American people to accept the court's verdict, defer to its wisdom, venerate its grandeur, unite around Bush and generally go quietly back indoors to await further instructions. Television is never more nauseating than when it slips imperceptibly into its role as quasi-official national nanny, instructing the unruly masses in correct civic comportment. But if the dissenting justices can pour bile on the majority's opinions -- Stevens explicitly accuses his conservative brethren of impugning the integrity of their judicial colleagues -- why is it so frightening for the people to do the same thing? The American people's allegiance to democracy should be greater than our fealty to a court that has just spat in its face. In any case, we survived His Fraudulency I, the unduly elected Rutherford B. Hayes, and we will survive His Fraudulency II.

What the court ruled, when you get down to it, was that democracy shouldn't be allowed to get in the way of bureaucracy. One man, one vote? Overrated. Every vote counts? Too much trouble. None of those democratic pieties, the court in its infinite wisdom ruled, are as important as strict adherence to niggling rules and timetables -- rules and timetables that the court itself had the power to set aside.

If a court received evidence that a condemned prisoner was actually innocent, but that evidence arrived five minutes after some subclerk's filing deadline, you would not expect it to simply blithely proceed with the execution on the grounds that proper paperwork had not been done. But that, in effect, is precisely what the Supreme Court did. And what it killed was not only any possibility that this election will ever be regarded as fair or final but the principle that every vote must be counted.

Of course, the Florida recount was flawed. The justices had legitimate reason to be troubled by irregularities in the recount process. The differing standards about what constituted a legal vote, left open by the vague Florida statutory language about the "intent of the voter" and the "clear intent of the voter," opened a Pandora's box -- start recounting without a clear standard and you're in an endless wilderness of enigmatic chads.

But the court's position that those irregularities -- which are comparable to the irregularities that plague every election in every state in the country -- violated equal protection rights and therefore are a matter for federal intervention, is indefensible. It's indefensible on grounds of judicial consistency, considering the court's long history of deference to the states in establishing and interpreting local law. But the real reason it's indefensible is factual.

If the recount violated equal protection rights, then the entire Florida election -- not to mention the national one -- did, too. As Gore attorney David Boies pointed out in oral arguments before the court (although he might as well have been talking to five potted plants -- those minds were closed), the different standards used in counting punch-card ballots have considerably less impact on which votes end up counting (the heart of the equal protection claim) than the different voting machines that are used. Optical scan devices, found in richer, whiter, pro-Bush counties, generate many fewer errors than punch-card devices, which are found in poorer, blacker, pro-Gore ones. Yet the U.S. Supreme Court did not suddenly drop its long-standing aversion to meddling in state affairs and rush into Florida to rectify this grave inequality. That apparently only happens when a fellow Republican needs rescuing.

In any case, even assuming that the differing standards used to evaluate punch-card ballots constitute grounds for federal intervention, there was a clear and fair solution, as suggested by Justice Souter in his dissent: Impose a statewide standard, to be overseen by a judge, and see if the recount could be completed by Dec. 18, the date set for the meeting of electors.

What harm would there be in attempting to carry out this remedy? The court made much of Dec. 12, the "safe harbor" deadline after which the frail craft carrying Florida's precious electors would be buffeted by unknown seas -- smashed by Hurricane DeLay, drenched by Tsunami Lott. But as all the dissenters pointed out, nothing in the Constitution requires states to send electors by that date. A safe harbor means exactly that: a safe harbor. Why not expose the electoral dinghy to those seas? What was the court so worried about? Could it be that, like the man to whom they served up the election, their real fear was that Bush might not win? How else to explain their refusal to pursue the option that many observers thought they would -- an evenhanded solution that would have guaranteed victory to neither man, honored the sacred principle that every vote counts, restored the luster to the court and prevented their legacy from being tarnished forever?

Instead of starting with the principle that the sacred duty of any court intervening in an election is to get the votes counted, and doing everything in their power to make that happen in as fair a way as possible, the five GOP justices simply declared that it couldn't be done because recounts weren't perfect and -- gosh, look at my watch! -- time had expired.

This argument is the epitome of probity, if you take your judicial philosophy from Kafka. The majority said the recount couldn't be done in time -- then smashed the clock with a hammer. They had the colossal gall to write, "A desire for speed is not a general excuse for ignoring equal protection guarantees" -- when they were the ones who halted the recount and imposed artificial deadlines that made that "desire for speed" necessary. As Justice Ginsburg said in her dissent, "The court's conclusion that a constitutionally adequate recount is impractical is a prophecy the court's own judgment will not allow to be tested. Such an untested prophecy should not decide the presidency of the United States."

It is difficult to avoid the degrading conclusion -- degrading, because it implies a substantial lack of judicial competence and integrity on the part of the court's majority -- that from the start the court's right-wing majority, like the Bush camp to which it has so many ties, secretly regarded the very idea of a recount as suspect, inferior, secondary, an ignoble and unacceptable tainting of the God-given, majestic, sacrosanct first-count results (which just happened to show Bush in a razor-thin lead). The single most frightening image of the entire surreal episode may have been James Baker's icy, contemptuous rage as he denounced Gore's request for a recount -- his scowling face almost a caricature of the left's cartoon image of the authoritarian, white-haired, vengeful, win-at-all-costs, God-is-on-our-side right-winger. The Supreme Court ruling had footnotes instead of rage, but it seems to have operated on the same assumptions.

Justice Scalia confirmed this with his bizarre defense of his order to stop the recount, in which he gratuitously said, "The counting of votes that are of questionable legality does in my view threaten irreparable harm to petitioner, and to the country, by casting a cloud upon what he claims to be the legitimacy of his election." It was prudent of Justice Scalia to include the words "what he claims to be," but does anyone really doubt that Scalia, like those Bush supporters who kept angrily braying that Bush had "won," believed that the Texas governor should by rights have already moved into the White House, and Gore's attempts to find out what the vote actually was were damn near treasonous?

This we-already-won mind-set explains why the court signally failed to look at the election as a whole, and craft a remedy that tacitly acknowledged the errors both sides made -- a ruling that would have been as politically wise as the one it issued was divisive and rash.

Courts are not explicitly political institutions, but when dealing with an issue as momentous as the election of a president, it would seem wise for the court to assess the entire context in which a given legal challenge takes place. The Florida election was an equal-opportunity debacle: Both sides acted wrongly and bear some responsibility for the mess. But no one objective could conceivably look at it and claim that the Democrats had overreached so badly that they deserved to be terminated by judicial fiat.

Florida's governor was George W. Bush's brother. Its secretary of state, who never ruled against him, was a high-ranking official in his campaign who hired a private voter-roll cleansing company with Republican ties that disqualified hundreds of legitimate Democratic voters. The Florida GOP illegally completed Republican ballot applications in Martin and Seminole counties while denying Gore campaign workers the same opportunity to correct Democratic ballot applications. It took every opportunity to disqualify improper ballots for Gore, while demonizing Gore for doing the same thing to military overseas ballots. Determined to ensure a Bush victory at all cost, the GOP-controlled Legislature voted to push a slate of Bush electors through -- regardless of what recounts might show. And, of course, the GOP dragged its feet at every turn, resisting recounts and trying to run out the clock.

The Democrats, for their part, lost the moral high ground by failing to call for a statewide manual recount from the beginning. They squandered more capital threatening to sue over a ballot designed by a Democrat. They ignored the obvious injustice of changing the definition of what vote should count in the middle of the process: Palm Beach's recount, in which the standard kept changing, was a travesty. And, like their Republican counterparts, they played hardball with every ballot they could get their hands on.

In light of this situation, a ruling that handed victory to one side and not the other was the last thing, from a political as well as an ethical perspective, the court should have been looking for. And fortunately for the court, a decision to remand back to the Florida Supreme Court would not by any means have ensured a Gore victory -- Bush was actually gaining votes by some accounts -- making it the right thing to do both legally and politically. Yet the court, in thrall to the idea that Bush had already won and, one suspects, secretly accepting the Rush Limbaugh crowd's canard that the hand recounts were not just subject to different standards but to malevolent Democratic manipulation and chad chomping, did not even try. It stopped the counting. It stopped the election. It stopped democracy.

Justice Ginsberg, in her dissent, summed up the case with quiet eloquence. "Ideally, perfection would be the appropriate standard for judging the recount. But we live in an imperfect world, one in which thousands of votes have not been counted. I cannot grant that the recount adopted by the Florida court, flawed as it is, would yield a result less fair or precise than the certification that preceded recount."

Thousands of votes have not been counted. Think about that, whatever your political persuasion is, from time to time during the next four years. Imagine them, gathering dust in a filing cabinet somewhere, each one of them expressing the choice of a person who, when he went to the polling place that Tuesday in November, had every expectation that the United States would do its very best to ensure that whether he was rich or poor, black or white, he would be heard.

The people have not been heard. They will not be heard. And each of those uncounted ballots is a cry of reproach against the act of judicial arrogance that has now forever silenced them.

Shares