President Bush and Secretary of State Colin Powell lasted about 10 days.

That’s all it took to abandon promises to keep the Middle East’s intractable Arab-Israeli dispute at arm’s length. Like President Clinton and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright before them, Bush and Powell now burn up the phone lines to Israeli and Palestinian leaders, to the kings and presidents of the Middle East. They call for calm, for negotiations, for low oil prices, for an end to incitement and violence and for solidarity against Saddam Hussein. Plus ça change.

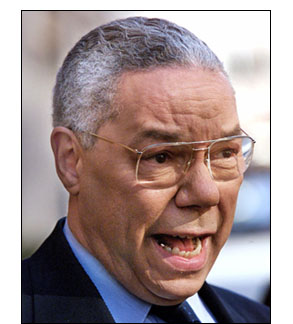

Powell’s solo trip overseas begins Feb. 23. He goes to Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, Syria and then to Kuwait for the 10th anniversary of his victory over Iraq as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The new administration is already learning that you can defeat an army, you can summon peace conferences and you can even get signatures on treaties, but pinning down peace in the Middle East is like mapping the shifting desert’s dunes.

Powell even briefly tried to outlaw the term “peace process” at the State Department, in the belief it had helped drag out moves towards peace. The new administration would talk about “peace” directly and deal with the region only when the parties themselves had decided to end their 50 years of war. That approach lasted less than a week, and Sunday even Powell was back on TV talking about the peace process.

Underlying America’s mothlike attraction to the Middle East conflict is fear of things spinning out of control, of massive violence and terrorism, of instability in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Morocco toppling friendly regimes and cutting off oil supplies. There is fear of how Muslims in Indonesia, Chechnya, Central Asia, Algeria, France, Turkey, Iran, Nigeria and elsewhere might react to an Arab-Israeli conflict.

So the Bush administration has found the Arab-Israeli dispute at the top of its foreign policy agenda since Inauguration Day, just like every administration before it since Harry Truman’s. Bush fired the U.S. special envoys led by Dennis Ross and tossed the grenade of Middle East policy to the regular State Department desk at the assistant secretary level. It was an attempt to downgrade the attention paid to the Middle East in the belief that the parties need to work on their own, without a big brother standing by.

But the first crisis came quickly, when hawkish Likud leader Ariel Sharon won by a landslide in the Feb. 6 prime minister’s race against Ehud Barak. Sharon then said that offers made by Barak and Clinton to give Palestinians 95 percent of the West Bank and Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem were void, a view the Bush team shared. Arafat had already rejected this, demanding all the land and the return of up to 4 million Palestinian refugees. Now Sharon has said he’ll only let the Palestinians keep the 42 percent of the West Bank and portions of Gaza they already hold, Jerusalem will remain Israel’s united capital, there will be no refugee right of return and he won’t negotiate till the Palestinians halt violence.

The fear in the Middle East is palpable. On Tuesday, an Israeli helicopter fired wire-guided missiles at a car, killing Masoud Ayyad, 57, a Fatah security official who Israel says worked for Hezbollah and had planned attacks on Israeli settlers. It was the latest of about a dozen of what Palestinians called “assassinations” and the Israelis called “targeted” killings of ringleaders in anti-Israel violence.

On Wednesday, it was Israel’s turn to mourn as a Palestinian driver ran a bus into a crowd of young Israeli soldiers at a bus stop, killing eight. The whole region is worried about how Israel will react once Sharon is in control, even if his invitations to Barak and peace advocate Shimon Peres to join his Cabinet as defense minister and foreign minister are accepted.

A violent clash could drag in Israel’s neighbors. No Arab country wants to fight Israel, which has military supremacy and is believed to have nuclear weapons. But things can get out of control, especially when the impassioned issue of the Al Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem is concerned.

I saw that firsthand at the last Middle East summit Clinton called at Sharm el-Sheikh last October. A portly Egyptian press officer in his shiny gray-blue suit sweltered in the sun next to the JollieVille Golf Resort clubhouse where Clinton, Barak and Arafat finalized an emergency plan to stop the bloody new intifada in the West Bank and Gaza and put the Oslo peace process back on track.

“We, all of us in Egypt, myself included, we want war with Israel now,” the press officer said. “The Israelis are killing the Palestinians, killing children. And General Sharon started it by walking in the Al Aqsa Mosque with his shoes on.”

Sharon never entered the mosque when he visited the Temple Mount on Sept. 28. But the rumor that he did was eagerly believed by the Egyptian press officer and many others. The day after Sharon’s visit the second intifada began and the 1993 Oslo peace process was in shreds.

Oslo collapsed when hawkish Israelis dragged their feet, continued to build settlements and kept control over Arab movements between their towns and villages that had been handed over to the Palestinian Authority. Frustrated Arabs flocked to the hard-liners of Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Those groups said Israel only listens to violence, which will internationalize the conflict, stir up popular movements in moderate Muslim states and get Europe and Russia into the peace talks to dilute U.S. support for Israel.

Oslo began to die just a few yards from where it began — on the grounds outside the White House. On a gray and bitter December day in 1999, Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk Shara opened peace talks with Israel at the Rose Garden by sounding the old hard line. His face grim and set like the weather, he did not even look at Barak or shake his hand.

Shara called for return of all “occupied land” without defining which land he meant. Was it the Golan Heights? The West Bank and Gaza? Syrian government maps of the area gave an indication of what Shara meant. Where Israel’s cities and towns have grown up in the past century there is only the name “Palestine.” The name “Israel” does not appear.

Shara’s icy blast was followed by peace talks at Shepherdstown, W.Va. But Syrian journalists there refused to talk to Israeli reporters at the next table. It was as if we were back in the 1950s when many Arabs believed they would one day defeat Israel, restore Palestinian refugees to Jaffa, Haifa and Jerusalem, and send the Jews back to Europe.

During the talks, while Israel was willing to hand back the Golan Heights for a peace deal, it refused to give back the final 10 yards that would restore Syrian access to the Sea of Galilee, Israel’s largest reservoir of fresh water. The talks ended in failure, as did a Clinton-Assad summit in Geneva last spring. Soon after, Syria gave the green light for attacks by Hezbollah guerrillas on Israeli troops in Southern Lebanon, which Syria occupies.

By June, Barak decided to cut Israel’s losses and carried out a hasty, unilateral withdrawal of its 1,500 troops after 18 years in southern Lebanon. That withdrawal would prove costly.

Anti-Israel hawks throughout the Middle East hailed the Lebanon withdrawal as Israel’s first retreat under fire from Arab land. Iranian envoys traveled through the region bringing cash and promises of weapons and support for anti-Israel attacks.

“Follow the model of Hezbollah,” said the Iranians and other hard-liners. “Israelis have grown fat, lazy and weak,” gloated the statements from Hamas and Islamic Jihad. “Israelis care about the stock market but they can no longer take losses in battle.” Waving Hezbollah flags, Palestinian youths stormed Israeli checkpoints with rocks and then guns as the new intifada began Sept. 29.

Israel bears much of the blame for the derailment of the Oslo land-for-peace process signed and sealed on the White House lawn in 1993 with a handshake by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Arafat. Despite a pledge to eventually give up the West Bank and Gaza, Israeli settlers there increased since 1993 from 150,000 to 200,000 this year, infuriating the Palestinians as they witnessed their land eaten up for new houses and roads.

And although Israel did turn over 42 percent of the West Bank and most of Gaza, placing nearly all Palestinians under Palestinian Authority control, the land between the towns and villages remained under Israeli control. This created the hated “leopard’s spots” geography.

“I work for a Western news agency, I speak Hebrew and English, most of my colleagues are Israelis and Americans but I am humiliated every day coming to work in West Jerusalem from my home in Ramallah,” a Palestinian journalist told me. It takes several hours to make a trip from Palestinian-controlled Ramallah or Nablus to Hebron, less than an hour’s drive, because of the Israeli army checkpoints at the edges of the cities and towns.

I once rode in a bus full of Palestinians through one of the checkpoints. The animated chatter died into a sinister silence as a 20-year-old Israel soldier in full battle gear entered the bus and passed down the aisle looking at identity cards. “The Israeli boys pretend to be angry but are afraid inside,” said one Palestinian afterwards. “We pretend to be afraid but are angry inside.”

Since the Oslo process collapsed into violence, the Palestinians have adopted the following strategy:

Israel’s strategy has been:

Sharon has said he opposes separation, recalling his pre-independence youth when Arabs and Jews shared the land. In a recent videoconference with Washington reporters he also said he will retain, no matter what the peace deal reached, control over the Jordan Valley to protect Israel’s eastern flank from Iraq.

Israel has had a rude awakening and gone back to the sense of being isolated and surrounded. Even Barak, whom Sharon asked to become defense minister, took a hawkish tone in a recent teleconference with Washington reporters. “The Middle East is not America,” he said. “There is no security for those who cannot defend themselves, no respect for the weak.”

What drags the Bush-Powell team into the conflict — and forces Israel to negotiate even with those who seek its elimination — are the new wild cards in the region: weapons of mass destruction and long-range missiles being developed by Iraq, Iran and possibly Syria.

Some say that it was the overbearing presence of the Clinton team that inadvertently caused the peace process to collapse and that Israelis and Palestinians may find it easier to reach common ground when faced with a less intrusive American presence under Bush and Powell. But the flurry of phone calls last week and the announcement of Powell’s trip may mean the U.S. will be just as involved as before.

And Powell’s visit to Kuwait will highlight the fact that control over the strategic region remains uncertain: Some lean toward peace, tolerance and accommodation but others listen to Saddam Hussein, Iran, Hamas and Hezbollah, believing that by violence they stand to increase their power.

What Powell brings to the region is his legendary victory in the Gulf War, his ability to get along with military and political leaders and his supreme confidence that with goodwill he can break through hostile barriers.

Both Arabs and Israelis believe Powell is a guy they can talk to and who understands them. So even after the personal diplomacy of Bill Clinton ran aground, the personal charisma of the new guy in town is likely to leave people in Riyadh and Damascus, as well as in Gaza and Jerusalem, with some hope of getting the peace process back on track.