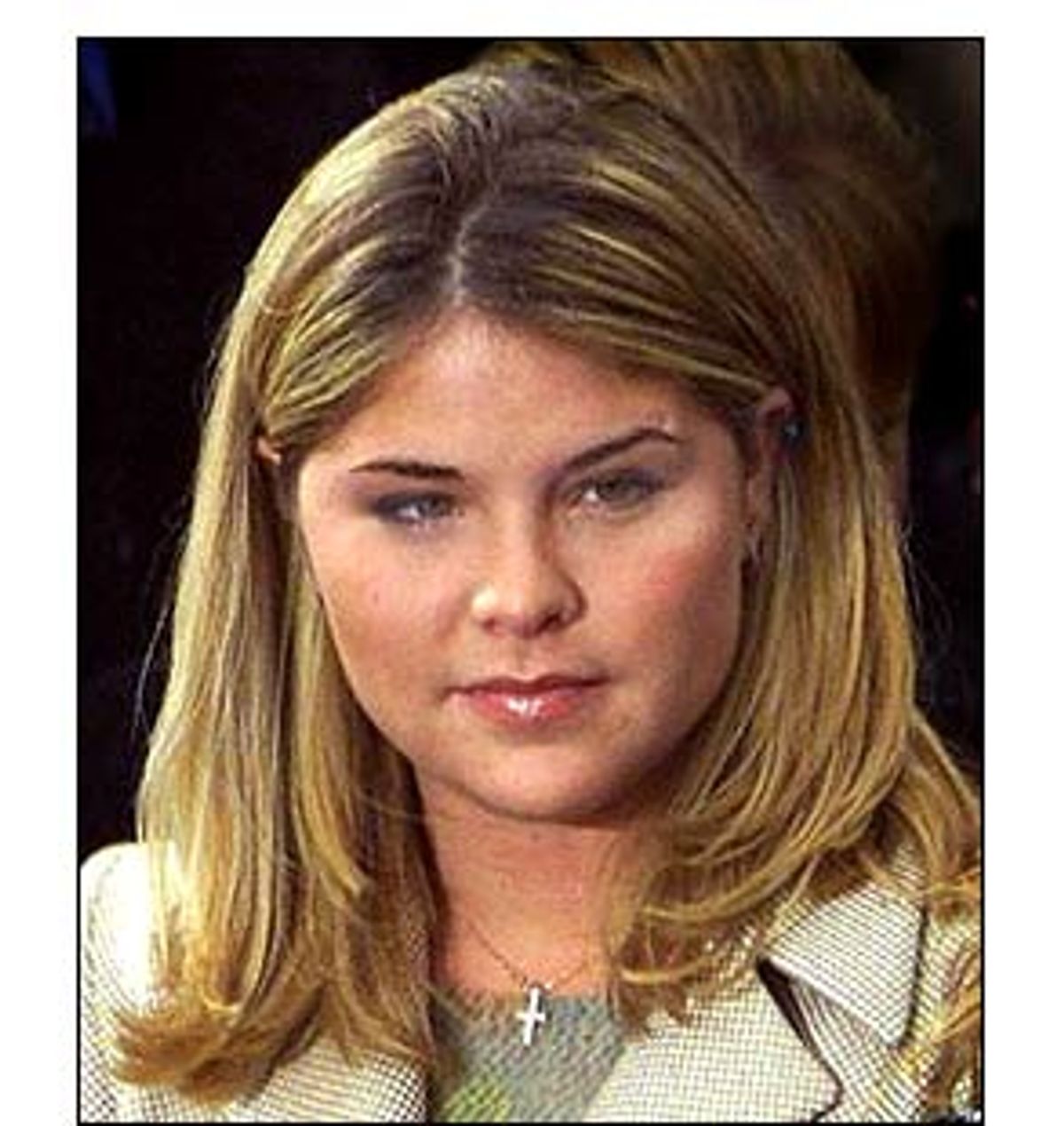

Party on, girl! That was my first reaction to the news that 19-year-old Jenna Bush had been busted for using a fake I.D. to score some Cuervo -- just a month after she was cited for underage drinking by Austin undercover cops. It was similar to my reaction when her father acknowledged that he had been a major party animal in his youth: It was the only thing I'd ever heard about him that I liked.

I have since had reason to rethink both reactions, of which more later. But it's worth examining why it was that I immediately found a dope-smoking, line-snorting, brewski-quaffing Bush more congenial than the same imaginary Republican cutout without those props. Call it the counterculture fallacy, a direct descendant of the Beat fallacy that preceded it by a decade: Lefties of a certain age, like me, still presume, in the face of massive evidence to the contrary, that a conservative who has messed around with mind-altering substances is somehow cooler, less straight, less, well, right-wing, than a conservative who hasn't. Leave aside the question as to whether either booze or coke qualifies as a mind-altering substance; it's reflexive for '60s vets to see Republicans who have "partied" as more enlightened than those who haven't.

Why? Part of it is that in those Greening of America salad days when you could still say "counterculture" with a straight face, conservatives came across as being opposed not just to liberation, sexuality and equality, but to sensation itself. We all knew that the Man wanted to lock down not just unorthodox actions, but unorthodox experiences. Whatever else it might have been, to seek out what Rimbaud called the "systematic derangement of the senses" was definitely to leave the paths trod by Young Republicans on campus. Our syllogism had all the logic of a Cheech and Chong exchange: Conservatives didn't get high: Ergo, getting high was progressive. The good guys got high; the bad guys didn't.

Alas, the equation of highness with holiness proved to be one of those '60s ideas that vanished in a puff of smoke. Smoking big spliffs turned out to be quite compatible with machine-gunning Bosnian Muslims. Drinking and taking drugs, it turned out, could be fun but could also lead to addictions and various pathologies -- bummer! And as for the Man, it turned out that he had been more of a party animal all along than we counter-culturists had ever dreamed. Those Episcopalian-bred stockbrokers and sturdy captains-of-industry in training liked a high old time just as much as their freaky cousins, and had more money to pay for it. Unbeknownst to pious lefties, a frat-boy party quickly sprang up next to the Rimbaud one, both of them listening to Hendrix and taking the same drugs -- but when the party was over, the frat boys still voted Republican.

That is, of course, the story of George W. Bush. But the crucial additional fact is that after the party was over, he made the penalties for doing what he did in his indiscreet youth much more severe. (The zero-tolerance law that may -- but probably won't -- bedevil Jenna was the work of his administration.) In that regard, those black-and-white '60s distinctions still hold true: At least the drug-tolerant lefties had the decency to respect the joyous impulse. Caught up in a sterile guilt-punishment formation we are all too familiar with, the conservatives hypocritically decry the very things they once eagerly did, with zero insight into why they did them. Once you realize that -- and just how profoundly formulaic, unenlightening and yes, conservative, Bush's "young and irresponsible" days were -- those impulses to welcome him into the brotherhood of roach-clip-handlers seem pretty idiotic.

Jenna's actions, by comparison, seem a lot more congenial. Her celebratory ways belong to a venerable tradition, that of the raucous student, the wing-testing youth. Which is why so many of us were taken aback by the moralistic hand-wringing and gloating -- much of it from commentators on the left, who are traditionally libertarian about substance use -- about a 19-year-old who got popped for drinking. Didn't any of these guys ever stand outside the 7-Eleven, like I did in high school a few times, trying to convince some 21-year-old to score them some beer? Give the girl a break -- she's just trying to exercise her God-given right to get twisted!

My colleague Joan Walsh declines to take such a light, Happi-Hour view of young Bush's recent troubles with the law and alcohol. In her view, Jenna and her twin sister Barbara (who was also cited for illegal drinking in the recent unpleasantness at Chuy's) are "acting out" against a pathological conspiracy of silence imposed by their father, a presumed alcoholic who, by his own admission, never told his daughters about his problem. In Walsh's view, the actions of the twins "seem designed to force a family reckoning that their father's drinking never triggered." The family drama being played out in Austin is "Long Day's Journey Into Bush."

Walsh's conjecture may well be true, but in my opinion it pushes the known facts just a little further than one can safely go with them. But buy it or not, her argument is fascinating because it raises yet another culturally contradictory aspect of the Bush presidency, one that also carries a host of subterranean assumptions about the way those on the left and those on the right handle their personal demons: Bush's problem drinking and the way he has dealt with it. Bush has never admitted to being an alcoholic, but because he did admit to having drinking problems that he addressed, he is about as close to being a 12-step president as we've ever had. (Ulysses S. Grant, mercifully, lived before the days of the Pledge.)

The fact that it's a right-wing Republican who is our first self-help president is deeply ironic. For people who overcome their personal problems, in our post-Freud, Oprah-ministered society, are supposed to go through some kind of metamorphosis, a sea change accompanied by deep and honest communication with everyone in sight. Yak yak get in touch with my feelings yak yak I feel your pain yak yak. But those moist, empathetic, talk-it-all-out qualities are totally associated with wimpy, bleeding-heart liberals; they're anathema to macho conservatives, who flaunt their repression like an oversized Texas belt buckle. John Wayne didn't need no stinking John Bradshaw lectures.

Bush's status as a strong, silent reformed drinker leaves him in a murky area, somewhere between the therapized left and the repressed right. And if only his personal behavior was in question, one might simply be content to leave it there. But his and his party's hypocritical drug and drinking policies make it only too clear that here, to use the '60s catchphrase, the personal truly is the political: It's hard not to conclude that Bush's draconian stance on mind-altering substances is the result of his unwillingness or refusal to explore his own youthful behavior, his dismissal of his deeds as simply "bad." They may indeed have been "bad" for him, but the first thing an examined life teaches one is that what is bad for thee is not necessarily bad for me. Moralizing stands in for insight: Every kid languishing in a Texas jail because he was caught with a joint can only regret that Bush didn't go to a few more therapy sessions.

As for whether he needs to go more Oprah with his kids, as Walsh suggests, I don't presume to judge. Jenna may be acting out, but it seems more likely to me that her recent problems are the result of a good old-fashioned desire to get wasted, perhaps combined with something she inherited from dear old Dad: a massive sense of entitlement, a knowledge that no matter what she does, no matter how idiotically she behaves, nothing will happen to her. How could Bush try to tell his daughter with a straight face that her actions have consequences? Forget the laundry list of Bush boo-boos that have been cleaned up for him, from the DUI bust that remained hidden for years to lingering questions about his National Guard record. We're talking about a young woman whose father drank away his youth, then benefited from a series of family handouts and string-pulling, and finally took possession of the White House after losing the popular (and perhaps the electoral) vote. Consequences? Consequences are for losers!

So party on, Jenna. The worst thing that could happen to you is you'll become president.

Shares