Last week, Hearst announced it was replacing Harper’s Bazaar editor Kate Betts with Glenda Bailey, who had until then headed another Hearst publication, Marie Claire. Reports following the announcement (which variously described tears, glee, disbelief and catty references to people’s wardrobes) made the fallout at Hearst sound like a scene straight out of “Heathers.”

For those who have missed the tsunami of ink surging from this particular teacup, Betts was shown the door after just two years, one year before her contract was up. Betts — one-time protigi of Vogue editor Anna Wintour and presumed successor to her post at Condé Nast — was hired by Hearst to take over the job of the legendary Liz Tilberis after her death from ovarian cancer in 1999. Over the next two years, the posh, Ivy League-educated Betts (whose mandate it was to bring a younger, cooler sensibility to Vogue’s biggest competitor) oversaw a much-criticized redesign, alienated much of her staff and saw single-copy sales of the magazine drop 7.4 percent in the six-month period ending in December.

But if Betts wound up playing an ineffectual Heather No. 2 to Wintour’s steely Heather No. 1, the ascension of Marie Claire’s Bailey to Hearst’s most glamorous post seems as improbable as having Martha “Dumptruck” Dunnstock elected captain of the cheerleading squad. While the still stylish Bazaar faltered under the chic, patrician Betts, however, its plainer but not necessarily smarter sister, Marie Claire, increased its readership by 50 percent under the leadership of frumpy, frizzy-haired, working-class Bailey — who was named editor of the year by Adweek despite her tendency to mispronounce fashion designers’ names.

Many of Betts’ supporters are horrified by Hearst’s decision, lamenting that Bazaar’s status as a fashion icon will suffer because of Bailey’s less than stellar sense of style. But as Alex Kuczynski wrote in the New York Times, Bailey has said that she does not intend to turn Bazaar into “a magazine about shopping, or makeup and baubles, or celebrity lifestyle, or spirituality and fitness, or how to get a date by Friday” and that in her heart throbs a genuine “passion for fashion.”

Besides, opines a frequent Marie Claire contributor, “Bazaar had been somewhat scattered and moving away from fashion since Betts took over.”

Still, Bailey’s editorial style is decidedly more reader-driven than Betts’, a style that seems bound to shift Bazaar down a gear from vaunted style icon to a more “get this look,” buy-by-numbers sensibility.

“My understanding,” says the Marie Claire contributor, “is that Bailey is a genius at gleaning what her readers want and serving it up, rather than imposing her own signature on the magazine. If they want the dish on the latest Blahniks, or if they want the old Harper’s logo back on the cover, Bailey will deliver — whether she’s wearing Ross for Less or whatever some designer has sent her that month.

“Whereas Betts was keen to put her stamp on Bazaar and erase the memory of Tilberis, because she knew how much she had to live up to. There was a bit of a smoke and mirrors diversion there, some flash over substance. Betts wanted to create a buzz by reinventing Bazaar and thus escaping comparison with Tilberis.”

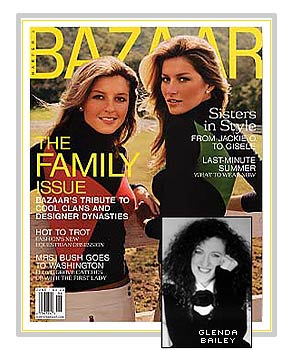

Still, it only takes a glance at the July covers of Marie Claire (“Angelina Jolie on Sex and Temptation,” “The Sex Tip Every Woman Should Know,” “14 Days to Flat Abs”) and Harper’s Bazaar (“A Tribute to Cool Clans and Designer Dynasties,” “Sisters in Style,” “Fashion’s New Equestrian Obsession” and, OK, “Laura Bush”) to guess which way the new Bazaar is headed. Ultimately, Hearst’s decision may have less to do with Betts’ (admittedly scattered) vision for the magazine than with the publisher’s desire to repeat the financial success of Marie Claire. As the London Guardian’s Carolyn Roux quoted one New York fashion editor as saying, “Under Liz, Bazaar was a sacred cow. But Hearst really wants a cash cow.”

Meanwhile, Condé Nast has been regretting some decisions of its own. Just one week before Betts’ ouster, Glamour editor Bonnie Fuller was handed her hat and shown the door. Ironically, Fuller was originally poached by Condé Nast from Hearst’s Cosmopolitan to bring some of that magazine’s trailer park appeal to the formerly more upscale title. If, ultimately, Betts turned out to be too Condé Nasty for Hearst, Fuller proved to be too Hearsty for Condé Nast.

Condé Nast may now be trying to shepherd Glamour back to its glamorous roots by hiring Cyndi Lieve (formerly a Glamour staffer under Ruth Whitney and, until recently, the editor of Self). But Hearst — in the unrepentant Christian Slater role (“Heathers” again) — seems intent on blowing the old school to bits. According to David Handelman of Mediaweek, insiders say Bailey plans to make the new Bazaar “more accessible” and at the same time “more intelligent.” As one editor well points out in the New York Times article, “that doesn’t make sense at all.”

If Bazaar winds up going the way of Cosmo, Marie Claire, Glamour and Mademoiselle — devoted in the main to tips ranging from catching a man to catching a man to manicures — then Vogue will stand alone and unchallenged as the fashion cheese; and the (Cruella) DeVilishly elegant Anna Wintour will eventually usher out an era.

Does it matter? Not really, unless you have a soft spot for chilly editrixes, Kay Thomson’s “Think Pink” number in “Funny Face” or Diana Vreeland’s imperious, outlandish pronouncements. If you do, then it’s a shame. Fashion magazine editors once embodied their publications and imprinted on them their personal style, not surefire recipes for affordable conformity.

Marie Claire was launched in France in 1937 as a biweekly magazine aimed at young, modern women. (Young professional women’s lives, the thinking went, were too fast-paced for a monthly magazine to retain its relevance over the course of a month.) Following the example of Marie Claire, French Elle, which has since introduced more than 20 editions around the world, launched in the U.S. in 1945; its emphasis on youth and on problems faced by “real” women, as well as its all-around populism, was iconoclastic at the time.

Elle was the first magazine to write about plastic surgery, unwanted pregnancies and what to do when you don’t have enough time to do everything — subjects that would have been considered either too taboo or too crass for Vogue. Elle’s founding editor, Helene Gordon-Lazareff, was perhaps the first fashion magazine editor to ponder what women might need or want from a magazine. Rather than hand down style diktats from on high, she provided cheerful advice and conspiratorial guidance to an emerging economic class. French Elle was also the first magazine to turn away from the icy high-fashion model and begin to feature younger, sexier, kittenish types — Brigitte Bardot was one discovery — in its pages.

But in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, Bazaar (under the editorship of Carmel Snow and the art direction of Alexey Brodovitch) was setting standards in design that remained unchallenged until Betts took over the magazine in 1999. Bazaar was a visual title that synthesized layout, typography, photography and graphic design to create a sense of elegance and style that went far beyond any individual item of clothing it presented. Bazaar was in itself a stylish object, a bound dream.

Today, most women’s magazines have gone the way of the early, reader-driven Marie Claire. (Ironically, Elle has remained more focused on fashion, arts, politics and culture than its down-market sisters.) Market research evidently shows that more readers are interested in “What Makes a Woman Irresistible,” “A Hairstyle That Flatters You!” or “The Compliment Every Guy Craves” than in “Fashion’s Equestrian Obsession.” And in a way, who can blame them? Where Vogue serves up another round of socialites month after month, Marie Claire brings you the real life story of “How Breast Implants Ruined My Life” — it’s just as prurient, but perhaps slightly less annoying. Which one speaks to you? Probably neither, but that’s the downside to populism — it aims for the middle but shoots low.

Meanwhile, as Condé Nast and Hearst play musical editors, and socialites and dental hygienists duke it out in their pages in the circulation wars, a new crop of fashion magazines — Jalouse, Nylon — and old/new establishment titles like i-D and the Face perform the Winona Ryder role in our “Heathers” analogy: Taking up the forgotten mantle of style, lighting up a cigarette as the old school burns, they easily walk away with it.