Sen. John McCain was frustrated. The senior senator from Arizona had picked up the paper one October day and read that the U.S. military had dropped only six bombs on Afghan targets the day before. He'd been holding his tongue, not wanting to fall into one of the media's favorite scenarios -- the hotheaded McCain still battling his GOP primary nemesis President Bush -- but this was too much. He told his chief of staff, Mark Salter, to start writing an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal, ultimately signed by McCain, that would urge the administration not to be afraid to wage an effective -- and thus ugly -- war.

"There were conversations about not bombing during Ramadan, worrying about the coalition guys, finding 'moderate' Taliban, 'We have eviscerated the enemy,' all of this kind of stuff," McCain told Salon. (On Oct. 17, a Pentagon spokesman, Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Gregory Newbold, director of operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said that "the combat power of the Taliban has been eviscerated." A week later, a different Pentagon spokesman would completely contradict this.) "I thought it was important to focus back on what our goals had to be," McCain said. "And while Ramadan is important, the coalition is important, refugees and innocent people being killed is tragic and terrible, all of them are secondary to getting our job done. That's what I was trying to say."

There was one word that didn't appear in McCain's op-ed, though it was always in the mind of the man who spent 5 1/2 years in a Hanoi prison camp: Vietnam. But last week the specter of Vietnam began to loom increasingly large, as critics began worrying that the United State's military might was proving ineffective against the rag-tag Taliban troops and wondering if America was going to be caught in a quagmire with no clear path to either military or political victory.

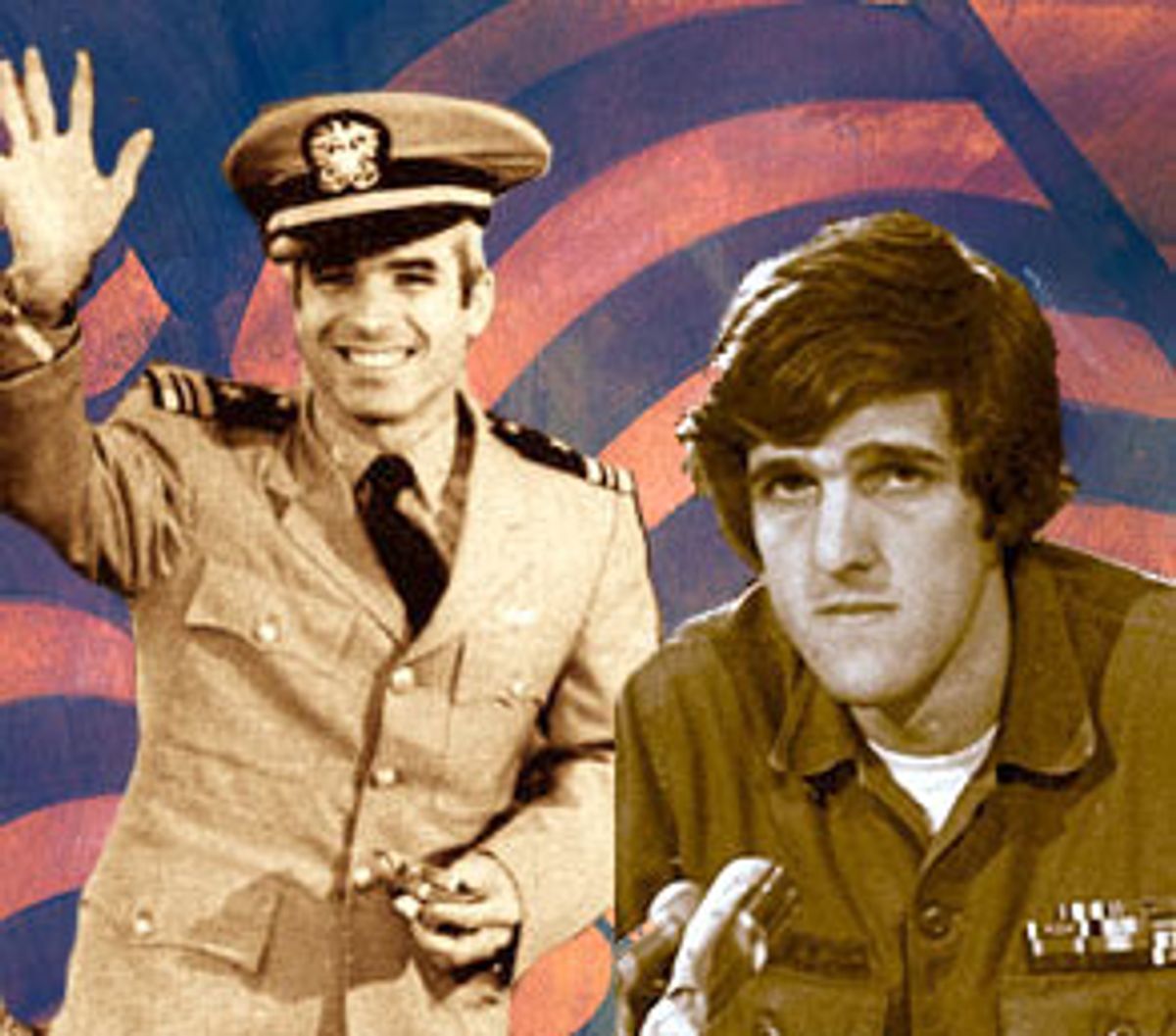

As the first comparisons to America's worst military debacle began to be heard, the two most prominent Vietnam veterans in American politics, McCain and Sen. John Kerry, D.-Mass., spoke with Salon in their respective offices about the war against terrorism and the challenges it poses. Neither of the two friends -- one a former presidential candidate, the other a likely candidate who has already amassed the largest campaign coffer for 2004 -- believes Afghanistan will turn into another Vietnam. But that doesn't mean they don't think there are plenty of lessons to be learned from that war with direct relevance to the current one.

President Bush groused that critics wanted an "instant gratification war," and others discounted the criticisms as armchair quarterbacking. Neither McCain nor Kerry share those views. Both men have serious concerns about the way the war has been conducted so far. To some degree, their opinions divide along party lines. McCain, like other conservatives, see Vietnam as a war that politicians didn't let the military win. Kerry, like other liberals, finds many reasons for America's failure in Vietnam -- including Pentagon duplicity. And unlike McCain, he is prone to bouts of uncertainty.

For all their differences of politics and temperament, the two senators share a unique perspective. As Kerry pointed out, veterans in politics look at the war somewhat differently from their colleagues who haven't served. They "know what hesitancy, political duplicity and fear, misjudgment -- however you want to characterize it -- what the impact is on life out there," Kerry went on. "John and I both share a belief that when you commit young people in the uniform of their country to an enterprise you owe them everything to support them, facilitate their ability to do the mission, to protect them. In other words, to not be reckless. And I think Vietnam was reckless at times. Leaders were casual about what they asked people to do without having a larger sense of the endgame, or staying power."

But Kerry and McCain have markedly different views on the legitimate use of force. McCain comes from the school that sees war as a horrible business only to be waged as a last resort -- but then with a commitment to the full use of force. Many of the foreign policy stances of the former Naval aviator -- who was awarded a Silver Star, Bronze Star, Legion of Merit, Purple Heart and Distinguished Flying Cross -- conform to this, like his early 1980s break with then-President Reagan against a U.S. military presence in Lebanon. (McCain didn't think the U.S. should have sent troops.) Or his Clinton-era support for U.S. involvement in Kosovo -- which came with expressions of disappointment that Clinton would not consider using ground troops (as he publicly proclaimed).

Kerry expresses similar sentiments. But, in character for Kerry -- a former Naval officer on a gunboat in the Mekong Delta, who came home from Vietnam with his Silver Star, Bronze Star and three Purple Hearts to form Vietnam Veterans Against the War -- his feelings are more complex, and perhaps contradictory. In an Oct. 28 interview with Brit Hume on the Fox News Channel, Kerry questioned some of the military targeting, expressing concern for "an enormous public relations component of this war. Almost an equal component of the war is the humanitarian part and the public diplomacy piece, because you have to avoid igniting the Muslim world." "But," Kerry went on, "the targeting, I think, of the military piece of it could be even more intensive."

Hume was perplexed. "Senator, let me see if I have this straight," Hume said. "You're saying that we're being too aggressive in our targeting of civilians and yet, not aggressive enough in our targeting of military targets? That we need to have such exquisite precision in our targeting that we don't hit any civilian targets and yet we have to somehow, at the same time, be more aggressive in what we're doing? Senator, do you think that is possible?"

Kerry insisted it was, saying that the U.S. should attack the Taliban front lines harder and be more careful about bombing near population centers. (If, as the Pentagon contends, Taliban forces are purposely relocating among civilians, the desire to separate the two may prove hard to realize.) Kerry seemed somewhat awkwardly caught between the hawkish desire to pursue all-out war and the dovish desire to avoid civilian casualties.

But these two schools of thought -- McCain's no-holds barred military mindset and Kerry's reluctant warrior/peacenik -- frequently unite, particularly on matters that might recall the war they fought in. Both men give Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld good marks. Both see the public as supportive of this war, as opposed to the one in which they fought. "The American people were never convinced -- even when they were supporting the war, and they were in the early years -- that this was a direct threat to the United States of America," McCain says. "They never believed that and they were probably right. We didn't think about it in terms of 5,000 Americans, innocent civilians, having been killed by VC."

Likewise, both men were upset when they heard another Pentagon spokesman, Rear Admiral John Stufflebeem, say on Oct. 24 that he was "a bit surprised at how doggedly [the Taliban] are hanging on to their power." The two men, with firsthand experience of the doggedness of the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong, winced at Stufflebeem's comments, which seemed to underestimate the Taliban in the same way that many accused the U.S. top brass of underestimating the Viet Cong.

"I was appalled by that briefing," says Kerry. "I was shocked by it. First of all, it runs counter to what most people who look at those folks and have studied them would say about them. These are hardened, devious, courageous, tough fighters. And all you have to do is look at what they did to the Russians and the British. That was an incredibly naove and conventional view being expressed."

McCain's take is less critical but no less disappointed. "He shouldn't have been" surprised, McCain says. "And even if he was, he probably shouldn't have said it."

McCain says he's concerned about a number of statements coming from the administration in the past few weeks: "When they say that the Taliban had been 'eviscerated' and it wasn't; when they say they're looking for moderate Taliban and there aren't any; when they say they don't want chaos to ensue and therefore ... we don't want the Taliban to fall too fast," he says. "At least in certain circles of the administration there was a misperception of the capabilities and tenacity of the Taliban."

But Kerry and McCain disagree as to how much the Taliban forces resemble the Vietnamese. McCain sees little in common, and likens the Taliban more to Cambodia's Khmer Rouge than to the Viet Cong.

"The VC were nationalists with a Communist overlay," he says. Afghanistan more resembles Cambodia in 1975, where "you had economic and social chaos in the country, so you have a very extreme group in charge. The North Vietnamese might have been cruel and oppressive ... but they were not the kind to kill someone because they were wearing glasses, as in the case of Pol Pot. Or, in the case of the Taliban, to shoot a woman in the soccer stadium because she watched a Western television program."

"There's a difference between oppression and insanity," McCain says.

Kerry, conversely, sees some definite similarities. The Taliban's habit of using civilians as shields reminds Kerry of the Viet Cong: "They'll be hiding in the towns, they'll come out and fight and then go back in and meld in with the population." Echoing American soldiers' complaints in that other war, Kerry predicts that "it's gonna be hard that way to tell who's Taliban and who isn't."

For this reason, Kerry says he was "delighted" when B-52s began carpet-bombing Taliban troops last week. "That's why we want to concentrate on them while they're concentrated in one place."

McCain, too, says that he was "very encouraged" by the introduction of the B-52s. "We learned from the Vietnam war that we can't dilly-dally around. The war in those days was graduated escalation. And you can't do it with graduated escalation."

Another Vietnam lesson Kerry thinks the United States should take to heart is "know your enemy." The United States underestimated the Vietnamese, he argues. To prevent that from happening this time, Kerry says he's been sending his 99 senate colleagues stories he thinks they should be reading, including one by former New York Times executive editor Joe Lelyveld on the worlds of suicide bombers and a Washington Post piece that profiled an Islamic extremist being held prisoner by the Northern Alliance.

Kerry voices a final lesson from Vietnam that doesn't seem anywhere near the forefront of McCain's mind: Keep peppering the military with tough questions. "I'm not going to sit out there like some potted plant on TV" and just mindlessly support the war, he says. The military, he thinks, has learned the lesson of Vietnam. And then, raising a thought that surely McCain would agree with, he says, "The question is: Will the politicians learn the lessons and stay out and give the military a mission and get the job done?"

Shares