It was five days after the attacks. My husband and I had fled Manhattan for his brother's place upstate to escape the acrid air and collect our shattered nerves. I was still having trouble eating and sleeping, and I'd brought my passport along, just in case World War III broke out overnight and I decided to slip across the border into Canada and fly home to Australia.

I was not one of the stoic New Yorkers. In fact, I was not even a New Yorker. But when I got an e-mail forwarded to me by a friend in London, I was upset on behalf of all 8 million of them.

The e-mail, written by a Chinese man, was an angry tirade against America and on behalf of Afghanistan and world peace, written in incongruently inflammatory language. The words "I don't give a shit," referring to the terrorist attacks and the suffering of Americans, stand out in my mind. The writer said that America had brought the attacks upon itself with its foreign policy, that Americans were soft and spoiled, that it was high time they got a taste of their own medicine.

I responded by telling my friend I'd found the piece nasty and offensive, and requested that she not send any more of the same ilk. I received a haughty reply stating that she and her friends were merely engaged in a rigorous international discussion, the implication being that there was something wrong with me, that I lacked the intellectual mettle to participate. I didn't know it then, but it was the first of many skirmishes to come. While flags sold by the millions and Americans spoke of their newfound sense of unity, I found myself at first divided and torn between cultures -- and then, increasingly, alienated from my own.

When I was 20 and living in Sydney, my ardent lifelong love affair with American culture -- partly born out of my youthful desire to escape what felt at the time like a suffocating, isolated island -- crystallized into an intense obsession with New York City. A few years later Australia grew on me, and my fantasies of living in New York faded into a nostalgic whimsy. But when I met and fell in love with a New Yorker, I found myself dreaming of New York again. While I waited for my fiancé's visa to come through I watched "Sex and the City" and tried to picture myself in its scenes.

Moving to New York also meant moving to America. I remember watching the news the day the USS Cole was bombed, the feeling of dread it raised in me, the sense of foreboding. I remember commenting to my father that Americans didn't realize how hated they were, and that one day it would all blow up. I remember phoning my then long-distance fiancé and expressing my fears of life in New York, of violent crime, and of living in a hemisphere beset by war. I remember the self-possessed calm in his reassurance that no one would be foolish enough to attack America itself, and the thin relief with which I tried to believe him.

Looking back now, I realize that our differing views of this potential arose partly out of geography. Australia and New Zealand are the most isolated "Western" countries on the planet. It is a distance that affords a uniquely clear outlook. At the same time this isolation casts a shadow of parochialism. The combination can result in a tendency to judge other nations and world events harshly and simply. It is this tendency with which I have been wrangling these past weeks.

I arrived in New York in December last year, and we married soon afterward. I was just feeling that I had finally arrived, and the beginnings of a bond with the city, when the planes flew into the towers, the Pentagon, and a sunny Pennsylvania field. The entire world was in shock, reeling with grief, gripped by fear, and overwhelmed by the psychic shift heralded by the "new reality." In the days following the attack I seemed to be in tune with my Australian friends back home, except that I was traumatized, having gone through it firsthand, or at least from the madness of the Empire State Building midtown. I shared my friends' concern that America might lash out in a bloodlust of retaliation. I recoiled from the American desire for revenge confirmed in polls. I agreed that the attacks were a wakeup call that demanded America reexamine its role in the Middle East, that it was an opportunity for America to own up to some of its more undeniable mistakes and wrongdoings and make amends.

But as the weeks passed and we all began to process the ordeal, review our history, and come to terms with the post-attack world and the war on terrorism, I became aware of an unsettling division -- between those who find America a convenient scapegoat and those who do not.

Polls will tell you that the majority of people in Australia and other Western, allied nations support America's war on terrorism. Many of those heartily support the commitment of their own troops. But what the polls don't tell you is that there is a sizable and extremely vocal minority who don't, and that beyond even this there is and has been, for as far back as I can remember, a palpable anger and hostility toward the U.S. in general. This minority is not confined to university campuses but stretches across a broad spectrum of society. Of course there is the "foreign policy is not a popularity contest" standard by which to measure this opposition, but if Sept. 11 and the "new reality" have taught us anything, it is that the hatred much of the world feels toward the U.S. can no longer be ignored.

That largely impoverished, uneducated and oppressed nations hate America is more or less understandable. Some of these nations are ruled by American-backed undemocratic and highly corrupt governments, and most of them have lived for generations with the riches of the modern world in view but out of reach, informed only by a government-controlled media. Anti-American sentiment in the Middle East is easy to fathom. But why does this hatred manifest itself in countries like Australia, Britain and France -- affluent nations that have much more in common with America than Middle Eastern and Third World nations?

In my recent dialogue with Australian family and friends, some predictable reasons have been given. One aunt declared that Australians' critical view of Americans dates back to World War II, when American troops were seen as "oversexed, overpaid, and over there." An Australian expat posting on the Web site Australians Abroad agreed. "My grandparents hated the Yanks and would tell stories of the Yanks coming into Brisbane on R&R and yelling out to the Diggers who were leaving on another train that they'd 'take care of their women for them,'" he said, before going on to confirm that some of those American soldiers did indeed "take care" of the Diggers' women and that a few were shot for their troubles. No doubt experiences such as these must have helped formed some national opinion, but there are just as many stories of camaraderie between Australian and American soldiers, and just as many Australians who feel a genuine sense of alliance with America. A cousin was quick to defend Australia's relationship with the U.S. "We know America would come to our aid if needed," she said. "It did when the Japanese invaded and Churchill said, 'Let them take it, we can get it back later.'" Run-ins during World War II or any other time don't account for the pervasive and vicious anti-American sentiment that has peaked in the wake of Sept 11.

The ANZUS Treaty, marking the Australia-United States alliance, was signed in 1951. The Australian prime minister, John Howard, was reportedly the first world leader to offer military support in the war on terrorism. Australian troops followed America into Korea, Vietnam and the Gulf War. Australia has participated in U.S. intelligence gathering consistently since World War II. There is therefore a sense that Australia, a relatively peaceful nation, has been dragged into America's troubles repeatedly. There is a pronounced anger toward the bind our military dependence on America presents. But why are some Australians so unwilling to acknowledge the rewards of this arrangement? Why are they so insistent on casting themselves as the hapless weak brother of the big buff bully? It is a clear case of risk and reward, and though the risks are real, and the dependence frustrating and unempowering, the rewards are great.

The refusal of the anti-American movement in Australia to address them is symptomatic of a largely complacent society. Australia is a wealthy country with a small population that couldn't possibly defend its coastline if it came under serious attack. It is a country that pays high taxes but which also enjoys good services. It has one of the most comprehensive health and welfare programs in the world. Its citizens live with the certainty that if they require medical care and cannot afford it, they will be given it, that if they reach retirement age without sufficient means of support they can draw a comparatively generous pension, that if they lose their job they can claim unemployment benefits until they find another.

All this is possible because it doesn't have to spend massive amounts of money on national defense. Many who were born and raised in post-World War II Australia, as I was, have little or no appreciation of the need for self-defense. In general Australians feel themselves so far removed, so relatively safe in their isolation, that they tend to view America as paranoid and hysterical when it comes to military defense. In my youth I, too, held this view; I indulged in the idealist, utopian fantasy of a world with no need for defense, imagining that Australia in particular need not concern itself with such unsavory preoccupations. My grandparents knew otherwise. I still hope for a future free of nuclear threat, for the realized potential of real world peace. But if and when it comes, it will come about as a result of a powerful organic human revolution. I am fairly sure it will not come about by pure fantasy, denial and anti-government jingoism. One thing is certain; we are not there yet, and it's not only the U.S. that lags behind in this evolution.

The current antiwar, anti-American sentiment in the West is not confined to Australia, however. Its voice can be heard right across Europe. The London friend who had sent the "I don't give a shit" e-mail went on to explain in further exchanges that the view of America she shared with many Brits was based on a kaleidoscope of grievances. "America's intervention in world affairs is often corrupt, abusive and hypocritical. U.S. foreign policy is highly destructive and sanctimonious," she declared, citing an article published in the Guardian in late September by Arundhati Roy as supporting evidence.

This friend, born and raised in a country settled as an English penal colony that grew into its own identity by resisting the class-based, culturally egotistical tendencies of the motherland, patiently explained why British culture was superior to American culture, with no visible sense of irony. She actually went so far as to make the claim that "We [Brits] are not as hysterical or ignorant as the U.S." It's probably accurate to say that the British, due to their proximity to Europe and the broader view of their media (at least their elite media) are more informed about the rest of the world than Americans, but this hardly precludes "ignorance" in general. And to claim that the British are less hysterical than Americans when the memory of the British reaction to Princess Diana's death is still fresh to us all is bold indeed. The enormous crowds and mass wailing in London in 1997 was far more extreme than New Yorkers' reaction to Sept. 11, and it was not three but roughly 4,000 people killed, not by accident, but by mass murder.

My London friend opened her litany of complaints with the perception of a U.S. public deluded by a pure-hype propaganda-machine media, and went on to cite America's military presence in Saudi Arabia, its conduct of the Gulf War, its responsibility for the starvation deaths of 100,000 Iraqi children as a result of economic sanctions (I've always wondered why this popular statistic only cites children, as if adults don't starve, or matter), and all the other well-known sins of America committed in the name of oil security. She climaxed with the widespread complaint against U.S. support of Israel, wound down with accusations of free-trade blackmail and two-faced global emissions policies, and finished with a description of the U.S.-led war on terrorism as a typical American aggression bound to add fuel to the fire.

In other discussions, a Canadian friend living in Australia wrote with absolute conviction that America's military action in Afghanistan was motivated solely by a desire for revenge and punishment, that self-defense "has nothing whatsoever to do with it." Someone else told me I sounded "like an American" simply because I questioned the caustic tone of the many recent anti-American letters to two major Australian newspapers. This same person attached to their message an article that posed the theory that America's war in Afghanistan is all about oil in the Caspian Sea, along with the heavy-handed Arundhati Roy piece, presumably to enlighten me. One letter in the Sydney Morning Herald's online edition stood out from the others. It was written by a Jewish woman who had gone to a peace march in Sydney's Hyde Park staged by the usually cuddly Friends of the Earth. She was horrified, she said, to find herself surrounded by a furious crowd chanting poisonous slogans against the U.S. and Israel. People calling for peace with voices of hate is perhaps the ultimate bleak irony of the current antiwar, anti-American movement.

There have been other long-distance frictions too numerous to mention. Of course some of these criticisms are valid and earned, but many are misguided and vulnerable to challenge. Few who cast these aspersions seem willing to acknowledge that even the most educated and informed among us rarely get the full political picture -- and many of those who are the loudest in their denunciations have far less than that. Yet even when they lack deep knowledge and information, many anti-Americanists are all too willing to assume the very worst of America in any given conflict, often downright whitewashing the other party.

It's not my aim to embark on an in-depth analysis of these charges or the degree to which they stick or don't stick; suffice to say that we all know the U.S. is not now, nor has it ever been, perfect. This is hard to accept; we don't want our superstars, or our superpowers, to be flawed, human, like the rest of us. What bothers me most about the anti-American sentiment I've encountered is not the criticisms themselves, simplistic as they frequently are, but the dogged superciliousness and smugness with which they are frequently expressed. There is a lack of real recognition of America, for better and for worse, inherent in this attitude. And there is an unsettling ease with which the United States of America is made the scapegoat for the flawed policies of the first world, the failings of some nations of the Third World, a library's worth of historical complexities, and the guilt of the privileged first-world individual.

It is the fashion, it seems, to hold the U.S. responsible for the hardships and struggles of the entire planet, some of which were germinating or already had a long history before America's existence. For example, many of the problems of the Middle East and Third World can be more rightly laid at imperial Britain's doorstep. Granted, America has stepped in where Britain stepped out, but that doesn't justify holding a New World country solely responsible for problems born of the Old World.

Anti-Americanism's broadest complaint is also its most powerful argument -- that the U.S. is too wealthy, too materialistic, too concerned with its own economic health to the detriment of the world's poor. The most powerful nation on the planet runs a laissez-faire economic system that dominates global economics. In Australia, where capitalism has long been tinged with socialism (though this hybrid is much diminished now), America's version of capitalism is viewed as ruthless. But if the problem is U.S.-led globalization and corporatization, there needs to be some acknowledgement of the way the rest of the world is participating. Furious finger-pointing at America ignores the option and responsibility of nations, communities and individuals to resist and protest what they find objectionable. The money in a citizen's hand does more voting than we ever get to do in a polling booth. Our consumer dollar is, now more than ever, a powerful political tool.

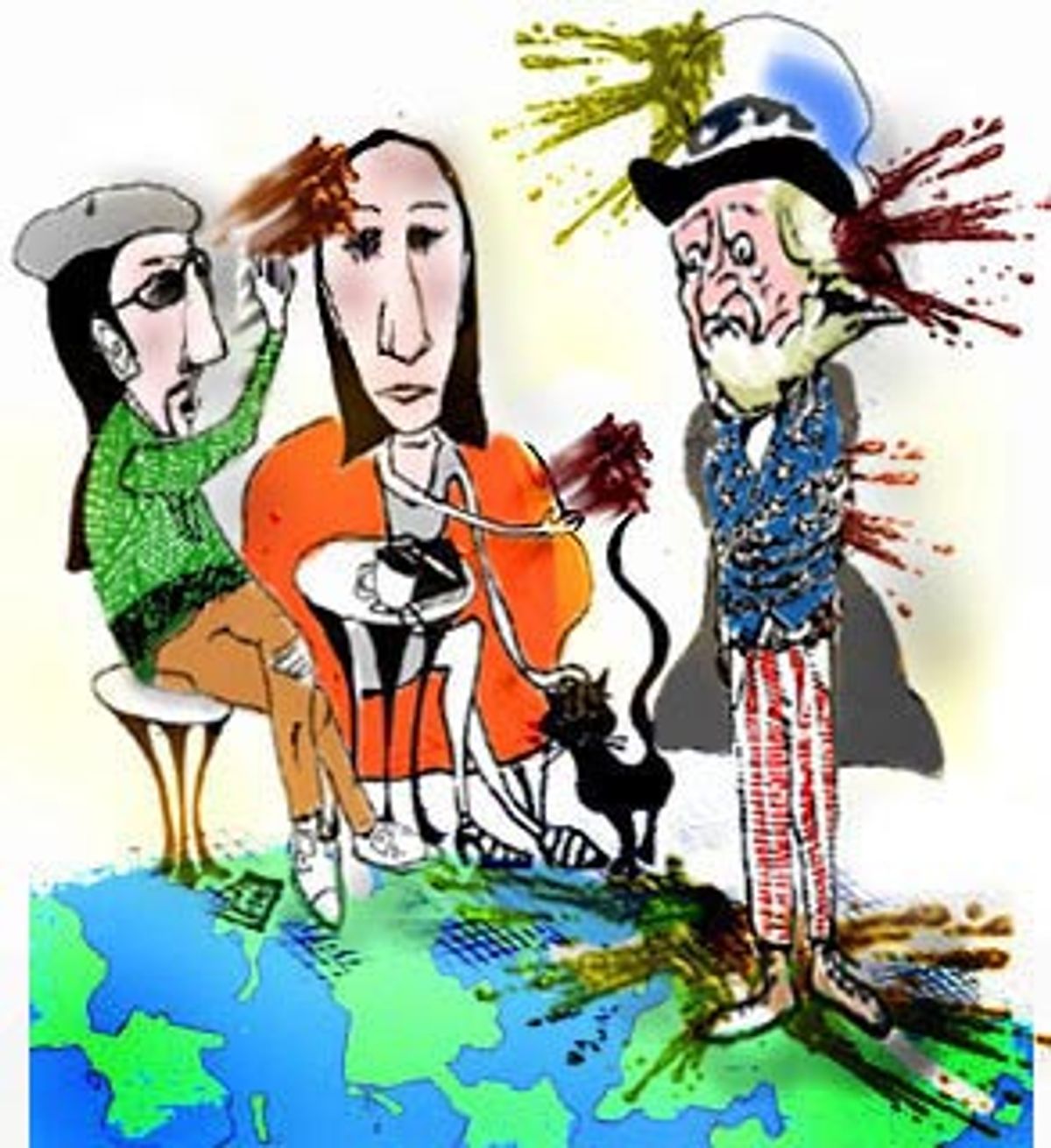

Too much anti-Americanism rests on bad faith. A psychological sleight of hand makes it possible for the anti-American movement across the West to enjoy privileges while avoiding a sense of responsibility for them. America has blood on its hands: The rest of the world, apparently, does not.

For some years now I have refused to eat at McDonald's and Burger King because I object to what I view as the unethical corporate practices of U.S. fast food chains. Neither do I buy products tested on animals to protest the global animal experimentation industry. I know many others who act similarly on their principles. But I have never heard of a person who refuses to use oil-dependent modes of transportation in adherence to their stance against America's oil-driven policies in the Middle East. I've met the odd rare individual who refuses to own a car because of their concern for the environment, but never anyone who boycotts oil across the board -- or even who devotes significant time to trying to change oil-friendly governmental policies. Why? Because it's a luxury people simply refuse to give up. Foregoing a lousy cheeseburger and shopping cruelty-free doesn't require a great sacrifice -- to live without using oil in the world as it is today would. That people don't wish to make this sacrifice is understandable, but that they demonize the U.S. despite their dependency on oil that may have been procured in association with U.S. policies is somewhat dishonest and hypocritical. Righteousness, it turns out, is the drug that soothes the fears and frustrations of exiled terrorist gurus and Sydney peaceniks alike.

I am more inclined to respect the voice of anti-Americanism when it produces more than simplistic critiques and -- at its worst -- hate speech. In other words, I am more inclined to respect it when it manifests an active rather than a reactive element. Unlike classic imperialism achieved by military-led expansion and domination, cultural and economic imperialism requires willing colonists. It is possible to resist so-called U.S. imperialism, as the small community of the Blue Mountains, northwest of Sydney, did several years ago when it successfully fought a bitter battle against the opening of a McDonald's in its quaint historic town. It is possible; it's just that most people would rather not bother. Victimhood is more appealing than self-responsibility, and when the villain is a big bumbling superpower it's an easy play.

Of course, being part of the problem doesn't oblige a person to silence. People have a right to be angry with the U.S. and its policies when they feel they're immoral, but they also have a responsibility to own up to their implicit participation. It's a democratic right to voice protest, but it's a matter of personal integrity to do so not from the moral comfort of a high horse, but while standing on one's own two feet.

Some anti-Americanists already do this, of course. Some, like socialists and anarcho-syndicalists, go further and campaign for radically different political and economic systems. But looking around at the anti-Americanists in my midst I see no home garage print-runs of "The Die-Hard Communists Weekly" or grassroots kitchen campaign meetings. I see people plucking the fruits, and treading the established paths, of capitalism.

And what of the confusions and contradictions of the left wing in the first world? In the two or three years preceding the attacks of Sept. 11, I received a string of e-mail petitions from alarmed feminists and leftists protesting the atrocities committed by the Taliban and calling for its brutal regime to be brought down. I signed and passed on every one without ever believing the petitions would literally achieve that end. It seems that others, though adult and educated, did believe in the power of these petitions to cause the Taliban to review in full the practices of its government. This is the only sense I can make of the turnaround of many of these same people, who are now on the front lines of the current antiwar movement. Some who were aware of conditions in Afghanistan under the Taliban's rule and who rallied against the world's complacency became, once America set out to topple the Taliban, its most ardent defenders, calling for peace at any cost, and casting America as the brute.

I understand these people are not really defending the Taliban; rather they are expressing concern for the innocent, already long-suffering Afghan people, and rightly so. But why the political backpedaling? Why oppose the forcible removal of the Taliban when they are clearly far too determined and well established to be removed by other means? This confusion, born of a demand that the sufferings of others be rectified coupled with a refusal to tolerate the realities of what is required to achieve that change, results in an impossible demand that the U.S. is accused of failing to meet again and again.

I came across an explicit example of this when reading an article in which a prominent member of a women's rights organization publicly retracted a previous statement to the effect that she wished someone would forcibly take the Taliban out. Sounding somewhat like a small and frightened child, she explained that she "didn't really mean it," that it had merely been an expression of frustration and not of a real and concrete desire for military intervention. That the U.S. military action in Afghanistan and its resulting refugee crisis and civilian causalities are painful, even tragic, goes without saying. But to believe in a world where dangerous people and tyrannical governments miraculously disappear seems infantile.

When I asked my French neighbor about the anti-American sentiment in France, she said there is a profound sense of "they had it coming" among the French left. When I asked her what the roots of French anti-American sentiment were she said simply, "Envy, jealousy. We think of Americans as arrogant, vain, self-centered. It is what France was two centuries ago: the center of the world." While I doubt this is all that fuels the anti-American sentiment there and across the West, there is likely some plain old jealousy in the mix. It's not an envy as tortured and confused at that of the Middle East, because we in the West are neither as uniformly religious or as economically deprived as the peoples of those nations. But it is tempting, it seems, to resent those more powerful and dominant, and to rally a reactive cause in response.

Some of this resentment boils down to that most basic of human emotions -- hurt feelings. Beyond the "Tall Poppy Syndrome" -- the famous Australian pastime of cutting gloating achievement, blatant success, and perceived arrogance down to size -- Australians often feel overlooked by America and Americans. I remember feeling angry that I didn't see Australia, a country with a fascinating history and political life, covered at all in the American media for months following my arrival. Even now I'm lucky to catch a passing reference or a feature in a travel section. And I've felt personally slighted more than once socially, when someone's eyes glazed over upon hearing the word Australia. Typically they'd vaguely mention Paul Hogan or kangaroos before losing interest completely. This hurt is, I think, a factor in the anti-American feelings of many peoples, especially Australians who get little attention on the world stage. It's a legitimate complaint, but it scarcely justifies the virulent condemnations that have emerged after Sept. 11.

Another comment my French neighbor made, recounting how a friend of hers in France had exclaimed bitterly on the phone, "They have six cases of anthrax and it's the end of the world. What about Rwanda?" illustrates another confusion of the left in relation to the U.S. -- the damned if you do, damned if you don't principle. America is criticized for not being a benevolent superpower when it doesn't intervene, and criticized for being the world police when it does. It is cast as an abusive cop when it steps into conflicts such as Kosovo, or accused of criminal negligence when it fails to act, as it did with the genocide in Rwanda. The U.S. itself suffers a certain amount of confusion in its foreign policy which gives rise to mixed messages, but whichever way it goes on any distant conflict the left seems insistent on meeting the U.S. with skepticism or conspiracy theories of ulterior motives.

Certain factions of the American left are no less virulent. A country, particularly a powerful one, needs a mindful and vocal conscience, and when it's doing its job, as it did during the Vietnam War, it's a vital watchdog. But Sept. 11 seems to have reduced even some Americans to sloppy accusations and irrational outbursts.

A prime example of this "America is the devil" silliness appeared in the Nov. 20 Village Voice. James Ridgeway's "Mondo Washington" columns titled "The Ugly American: Bully Spends Billions Blasting Nation of Refugees," "The Lost Colony: Afghanistan's Huddled Masses" and "Brown Out: U.S. Drops Bigger Bombs on Darker People," were the most stunning displays of frenzied knee-jerking in the name of journalism I've witnessed in a long time. In one short page he managed to hold the U.S. government responsible for the deaths of 7 million Afghan refugees (most of whom are not even dead), to refer to Afghanistan as an American "colony," and to suggest that the use of the dreadful "daisy cutter" in the bombing campaign was inspired by a racist impulse to "get rid of these nasty tan bugs."

As Christopher Hitchens pointed out in the December Atlantic Monthly, some in the American left and other "progressives" "have grossly failed to live up to their responsibility to think; rather, they are merely reacting, substituting tired slogans for thought." Or in Ridgeway's case, hysteria for thought. There's a certain laziness involved. It's not necessary to challenge oneself and grapple with impossible problems, it's not necessary to read extensively across a wide range of views (not only those that confirm one's most comfortable and staid thinking and beliefs), or to educate oneself on the intricacies of history and geopolitics in order to be certain which governments should be held accountable for what sufferings, when one can, without going to all this trouble, satisfy one's need to assign blame and take the high moral ground by making the U.S. accountable for everything, even deaths that haven't happened.

After many trans-Pacific and Atlantic conversations I've come to see the escalating anti-Americanism as the product of, to varying degrees, a tendency toward black and white thinking, a heartfelt concern for the suffering of disadvantaged peoples, and the denial of our own most rapacious capitalist selves -- as projected upon and epitomized by the U.S. The stridency of this habit of thought is laced with wishful thinking and is driven by a lack of equanimity fostered by the new reach of global terrorism. People are afraid. They want to believe that if only America had not responded militarily, if only it had seen the error of its ways and had met the terrorist demands by pulling out of the Middle East, everything would be all right. They would not had have to send their troops, they would not have to fear future attacks on their own soil, they could go to sleep in the knowledge that World War III is an imaginary nightmare rather than a present day potential.

It's an understandable conclusion, one I also entertained in the awful days following the attacks. The problem with it is that it underestimates both America and the terrorists who have declared war on it, if in totally different ways. I've been struck by the apparent sense of confidence some anti-American westerners have in the terrorists. I've even stumbled across a few apologists. They seem to hold the view that the terrorists are somehow reasonable in their endeavor, that they would surely end the terror if they got their way. One Australian, again posting on the "Australians Abroad" Web site, stated, "Remember even the fanatics of 9 Sept [sic] didn't do this to maximize kill ratio ... hitting a sports stadium with gas would have taken out thousands more." Apart from the fact that "hitting a sports stadium with gas" is not as easily achieved as this poster imagines, it's a preposterous notion that the perpetrators of this attack were in any way concerned with minimizing civilian casualties. The poster went on to argue his point by claiming that the terrorists had chosen "light flight loadings" guided by the same noble impulses. Apparently the idea that they'd chosen lightly booked flights because it meant less chance of passenger resistance and therefore a greater chance of success was not familiar to this well-meaning young man. But this fantasy of "almost" freedom fighters with an "almost" just cause is as prevalent as it is problematic.

What we know about bin Laden and al-Qaida suggests a very different potential. The theory that bin Laden's true focus lies in leading a fundamentalist Islamic insurgency right across the Muslim world seems to have some weight. If that is his mission statement, America's abstention from military action and wholesale backing out of the Middle East might well have had two immediate consequences: an oil crisis and a series of successful insurgencies. The world economy would have become unstable, and a significant portion of the world would soon be under the rule of fiercely repressive Taliban-style governments -- but this time with nuclear capabilities. Who knows if they'd stop there? Islam has a proud history of expansionism. I suspect that then the anti-Americanists -- Australians, English, Europeans, feminists, and peaceniks alike -- would have a sudden change of heart.

I realize this is a dark and somewhat alarmist scenario. We have no way of knowing if it could have happened because America did, predictably, attack. And, of course, as the antiwar movement would be quick to point out, the U.S.-led action in Afghanistan carries its own risk of inciting insurgencies. However, they could not proceed as quickly and as smoothly as they might have had the U.S. simply withdrawn from the whole region at bin Laden's demand. I'm not suggesting that a U.S. withdrawal from Saudi Arabia is impossible or undesirable, only that there are problems with the assumption that America's "understanding" and tolerance of the terrorist cause as stated could or would have spared further conflict and escalation.

While many of my friends overseas promote stereotypes of America and find affirmation from each other in doing so -- Americans are blinded by their own inflated self-image, they fall prey to their government propaganda mindlessly with no self-examination, they revel in their ignorance of other parts of the world, etc. -- I see a different America. I see a grieving, vulnerable America shocked out of its self-absorption, an America that is indeed questioning, debating, and attempting to understand the root causes of its predicament, seeking to educate itself about Islam and Muslim cultures, seeking to defend itself against further attacks. I see an America that has welcomed more people from more countries around the globe than any other country in the history of mankind. I see an America whose embrace of democracy and vision of freedom, however less than perfectly realized, beats in every American heart. I see an America that deserves compassion in response to its misfortunes, and acknowledgement of its virtues and better strivings, however often they may fail or produce unforeseen consequences. And I see a world that would be less without it.

Shares