What job gives you irresistible sexual magnetism, optional anonymity and a comprehensive nervous and physical breakdown?

The correct answer isn't prostitution, but it does rhyme with it: execution, a line of work routinely ignored by career counselors despite the powerful draw it has had for people through the ages who seek a relatively safe, government-sanctioned outlet for their primal urge to kill.

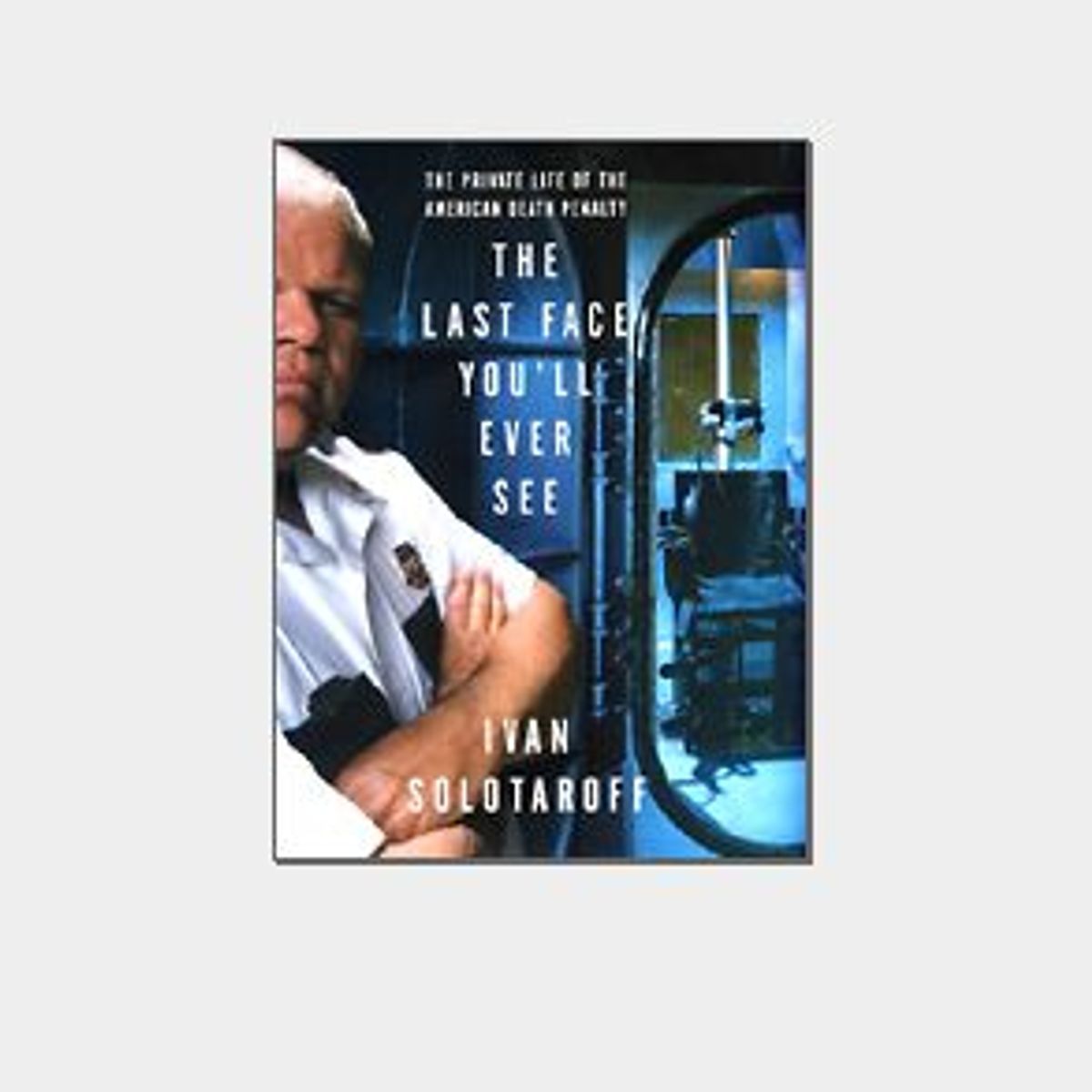

The life of the professional killer with a state government paycheck is the subject of Ivan Solotaroff's "The Last Face You'll Ever See: The Private Life of the American Death Penalty." Solotaroff's first offering since his 1994 collection of essays "No Success Like Failure," this ambitious book attempts to penetrate the inner lives of two men whose job it was to asphyxiate convicted murderers in Mississippi's gas chamber in the 1980s and 1990s.

Solotaroff's subjects present a study in contrasts: the hot-headed, obese, self-described Southern redneck Donald Hocutt vs. Donald Cabana, the thoughtful, sensitive warden with a masochistic habit of befriending the condemned. The first Donald approaches his work, at least initially, with something resembling zeal; the second with dread, grief and ultimately crushing guilt. Hocutt remains a death penalty supporter to the end, while Cabana ends up penning a 1996 "confession" repudiating his old line of work.

But both men, corrections officers at Mississippi's Parchman State Penitentiary, wind up wasted in body and spirit. While Solotaroff claims a neutral stance on capital punishment, his unmistakable conclusion is that the work of putting people to death is ultimately every bit as lethal as breathing carbon monoxide in a sealed room -- it's just slower.

The book opens with a contemporary scene in which Hocutt -- riddled at age 42 with gout, diabetes, diverticulitis, arthritis, partial deafness, obesity, depression and constipation -- returns to the prison after his retirement to get a form stamped for his medical discharge.

Solotaroff, accompanying the sickly executioner, finds himself fixating on Hocutt's equipment.

I can't take my eye off the Colt. [Solotaroff writes] "Donald," I say, touching the barrel. "That's a big gun."

"That's a dangerous gun," he says softly. "Maybe you don't want to be touching it."

This breathless prelude offers a sample of the fawning that characterizes much of the portrait to come, but before we can circle back and find out what brought Hocutt to this odd combination of erotic charisma and well-armed ill health, we are taken on a wildly disorganized detour through the thickets of execution history and politics. By the time we catch up again with Hocutt 69 pages later, we have practically forgotten him, glutted as we have been with scenes and statistics from the death penalty annals; gruesome tales of botched executions; lengthy interviews with opponents, prosecutors and death row convicts; and Solotaroff's miasmic musings on the moral significance of capital punishment.

Solotaroff's analytical passages often invite rereading in order to clarify how little sense they make.

A contemporary American execution, scorned by abolitionists abroad and at home as a form of moral backwardness, is probably nothing of the kind. Like mid-nineteenth century slavery, it is rather our "peculiar institution" -- and as anyone who has toured a death row or attended an execution can attest, the will to enslave and the will to execute are either the same or remarkably similar.

Fortunately for our common notion of "moral backwardness," in the book's sprawling first section, Solotaroff sticks mostly to the less hazardous and more vivid turf of anecdote. Of keenest interest are the tableaux illustrating the contribution of American technical ingenuity to capital punishment, particularly with the application of electricity (by no less an inventor than Thomas Alva Edison) and then poison gas.

The electric chair -- until 1991 America's most common method of execution -- disturbed witnesses and executioners alike when it was revived in 1979 after a 13-year hiatus. At the 1983 electrocution in Louisiana of Robert Wayne Williams, Solotaroff reports that wardens and onlookers were "surprised," "baffled" and "amazed" (inescapable is the image of an irate editor, frantically crossing out the verb "shocked") that the condemned man smoked and sizzled long after the voltage was cut, and despite the best efforts of his morticians stubbornly persisted in smelling like cooked flesh a full 24 hours later. Mourners were unusually brief in their goodbyes.

Capital punishment's next technological advance was the gas chamber. An American invention much admired by the Third Reich, the new method provided witnesses and executioners with another memorable spectacle: "A Tucson television reporter sobbed uncontrollably during [Donald Eugene Harding's execution on April 11, 1992, in Arizona's gas chamber]; two other reporters 'were rendered walking "vegetables" for days'; the attorney general vomited halfway through."

Such is the effect on witnesses. So what about the executioners?

In Solotaroff's anecdotal historical survey, the severity of job-related stress in the execution trade varies widely. Thousands of people applied to be Sing Sing's executioner when the position opened up in 1940, "despite the fact that [the prior executioner's] house had been firebombed in his second year on the job, and that the previous executioner ... had blown his brains out two years after retiring."

But others emerge from a career in capital punishment relatively unscathed. Indeed, the executioner's career path has on several occasions led directly to the White House. Erie County sheriff Grover Cleveland hanged two men in the early 1870s before ascending twice to the presidency, Solotaroff reminds us. (Modern instances of presidential candidates executing their way into the Oval Office the author has apparently judged too recent and obvious to mention).

Still, the combined burden of both conscience and notoriety has led governments to hide their employees' identities. Take Florida's hooded executioner: Hired through the classifieds, the successful applicant is collected at an agreed-upon spot, hooded until he or she is done with work, and finally deposited, with a check for $150, at the pickup location.

Often the state takes pains to obscure the executioners' identities from themselves. Some schemes position placebo executioners next to real ones, none of whom knows who's injecting saline solution and who's injecting pancuronium bromide, or who's pulling dummy levers for the gas chamber or electric chair. Even more elaborate is the commissioning of software to randomize the choice of which lever actually starts the mechanism. Some states mandate that the requisition must be done in such a way that the programmers don't know they are writing code that will launch, say, a gas chamber as opposed to a watering system, lending new significance to the term "vaporware." Mississippi isn't big on these anonymizing niceties, so Hocutt and Cabana are left with a pretty clear idea of what they do for a living. The knowledge is particularly hard on Cabana, with his tendency to befriend death row prisoners for the months if not years it takes the legal system to approve their executions.

While Solotaroff usually quotes out of his depth, fecklessly invoking the likes of Camus, Yeats, Christ and Sophocles, he does luck out with Cabana's Shakespearian illustration of his own guilt:

"You got me thinking about Edward Earl again, the night he was asphyxiated [Cabana tells Solotaroff]. I was in the shower two hours later, scrubbing and scrubbing. Then I showered again. I just couldn't get the sweat and grime off me to the point where I felt clean enough to go to sleep."

Cabana's arms tighten on his chest and he starts rocking. "It hasn't come off me yet."

A hygiene OCD worthy of Lady Macbeth is just the first of Cabana's guilt-induced maladies. Tormented particularly by lingering questions about Edward Earl Johnson's guilt and the execution-hour absolution offered by Connie Ray Evans, Cabana ultimately suffers three massive coronaries, capped by a quadruple bypass. Prior to an earlier operation, terrified he won't live through it, Cabana begs a priest to absolve him of responsibility for the executions. The priest demurs.

Yet both Donalds are curiously obtuse about the cause of their own suffering. Hocutt predictably answers questions about his guilt with bravado and denial; even as he prepares to file for his medical discharge and calls in to refill his antidepressant prescription he disavows regret for a single execution. Even the more introspective Cabana seems in a fog when it comes to self-examination.

"I'm an innocent man," Cabana insists moments after he recounts begging the priest to absolve him. "There's no guilt breaking my heart."

Nonmedical questions of the heart, alongside those concerning less exalted organs of human feeling, are Solotaroff's most compelling subjects. Everyone knows of the erotic allure of the condemned murderer; without it Gary Gilmore could hardly have become Norman Mailer's hero, and Richard Ramirez would not have gotten such a prodigious volume of perfumed mail. But who, outside the S/M community, knew that the executioner had similar charms?

Donald Hocutt, that's who -- and it's not only the author's fascination with his "big gun" that Hocutt has to contend with. "Ever since Jimmy Lee Gray," says the corpulent, unwell corrections officer, "people have been wanting to touch me."

An argument could be made that Hocutt's allure has to do less with sexual desire than with a pure fascination with mortality in general and murderers in particular, with the death-defying thrill of touching a professional killer and living to tell the tale. The relationship between the executioner and the condemned, however, is fraught with an undeniable and undeniably yucky intimacy.

"In execution rites of the Middle Ages, the condemned were expected not only to forgive the executioner but at times to physically embrace him," Solotaroff writes. "Execution was punishment but also a kind of marriage; two humans joined under a bond that both understood and transcended the actions they were about to take."

This 'til-death-do-us-part bond is Cabana's nobility and his Achilles heel. He ministers to the condemned, he befriends them, he prepares them for their deaths, he kills them and then -- whatever anyone may say about what's responsible for his weak ticker -- he dies a little.

The epitome of the nuptial execution comes with the killing of Connie Ray Evans, condemned in 1981 for the murder of a convenience store worker during a robbery.

"I'm killing a friend of mine tonight," Cabana reflects as Evans is strapped into the gas chamber. Solotaroff writes, "In the classic image, he knew, a part of the executioner dies with his prisoner. Now it was palpable. Cabana felt a part of his life slip away."

It should not surprise us that a man cursed with Cabana's sensitivities would form such a bond with his doomed prisoners. But the depth of feeling between Cabana and Evans is, amid all the blood and guts and torture and self-torment, the dramatic heart of the book.

When asked if he has any final words, Evans asks to say them privately to Cabana. With great symbolic effect, he summons the executioner into the gas chamber.

"I love you," Evans tells Cabana. Minutes later, just prior to giving the order to release the poison gas and begin Evans' 15-minute final ordeal, Cabana mouths his reply: "I love you, too."

What could it mean for a condemned man to love his executioner, and for that love to be reciprocated? The possible explanations for such a bond go beyond the pop-psych associations of sex and death to include the vastly more perverse strain of parental feeling. Parents feed, house, clothe and counsel their children to prepare them for adult life; Cabana and executioners like him feed, house, clothe and counsel their inmates to prepare them for the next life. How could they not bond?

Solotaroff illustrates the parental strain of the executioner's psychology with a passage in which Cabana's and Hocutt's predecessors clean the body of their first gas chamber kill after years of using the electric chair: "Compared to the disfigured bodies that emerged from the electric chair," Solotaroff writes, "it was like washing a newborn."

But the love that blooms on death row may grow most significantly from the curious reversal that happens in the process of execution: In dispatching a murderer, the executioner becomes one. Simultaneously, the original murderer becomes a victim. One murderer is lawless, the other lawful, but the executioner, in all likelihood lacking a criminal's cold-blooded conscience, may undergo a more severe form of guilt. He may feel more a murderer than the condemned does.

Even the most callow executioner winds up bearing a burden that belongs, originally, to those who order the executions in the first place, namely the residents of death penalty states. That's why we hire him. The victims' rights crowd crows that they would gladly pull the lever themselves, and it's true that every job opening in the capital punishment industry brings on a cascade of applications. But the reality of the job, the weight of a society's outsourced vengeance, blood lust and guilt, breaks men in half.

It follows from this that the death-row love bond may arise from the executioner's and condemned's sense of being on the same side of a destructive force beyond their control or comprehension, one that is bearing down on both of them and stripping away their lives. A crime has been committed; a life or lives have been taken, and society calls out for justice and revenge. Whether they know it or not when they apply for the job, the executioners as much as the condemned wind up our collective sacrifices.

Shares