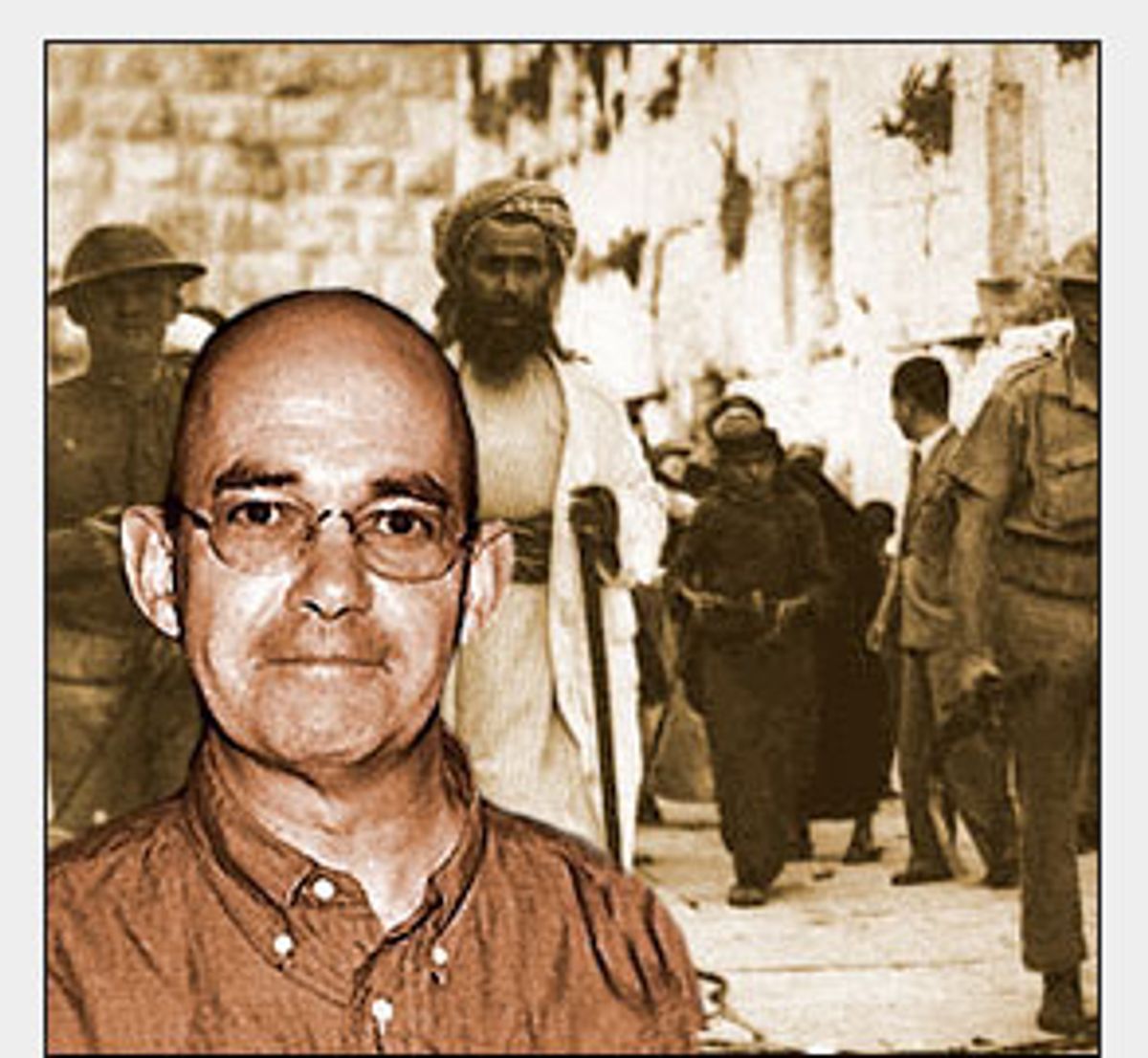

Israeli historian and journalist Tom Segev is accustomed to controversy. Segev's books, which include "1949: The First Israelis," "The Seven Million: The Israelis and the Holocaust" and his latest, "One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate," have been bitterly attacked, both in Israel and abroad, and just as vehemently defended. With his fellow "new historians," who include Benny Morris, Avi Shlaim, Simha Flapan, and Ilan Pappé, Segev has challenged the most cherished assertions about the founding of the state of Israel, claiming that the Jewish state bears a far greater share of responsibility for the Palestinian tragedy than traditional Israeli historians were willing to accept.

In his new book, Segev turns to the British Mandate -- that momentous 30-year interval between the end of World War I and the creation of the state of Israel in 1947 when Britain ruled post-Ottoman Palestine and tried, with increasing desperation, to prevent two budding nationalist movements from turning on each other and their British masters. A journalist (he writes a column for the major Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz) as well as a historian, Segev is a master storyteller, adept at mining historical archives for dramatic stories, mingling remarkable personal tales with the larger movement of history. The conclusion to his gripping story is pessimistic: He believes that the Zionist project and the Arab national movement in Palestine could not coexist, and that violent conflict was therefore inevitable.

An especially controversial aspect of Segev's book is its assertion that the British were more pro-Zionist than many Israelis have traditionally believed -- and that Israel therefore owes its existence, in large part, to the British. Segev claims that a major reason for British support for the Zionist cause was a quasi-mystical belief held by many senior British officials that the Jews had extraordinary power in world affairs -- a belief made up of equal parts Christian philo-Judaism and anti-Semitism. Segev's thesis that the British tilted toward the Jews -- and in a larger sense, his objectivity -- was attacked by Tel Aviv University professor Anita Shapira, who argues in a long New Republic review that Segev makes selective use of sources and twists the evidence against the Jews and towards the Arabs. But other reviewers have lavished praise on "One Palestine," citing its fairness, its rich panoply of characters and its historical sweep.

Segev spoke with Salon by phone from his office at Rutgers University, where he is a visiting professor this year.

You're considered one of Israel's "new historians," a movement that has been very controversial within Israel. What was the Israeli reaction to "One Palestine, Complete"?

There was a tremendous reaction. It immediately became a bestseller. Everybody talked about it. For a while, it seemed as if a wave of nostalgia was sweeping the country, as if people wanted to go back to the British Mandate. Obviously, some people said that I'm wrong. Some Israelis and some Palestinians had all kinds of criticisms about the book which, of course, is OK and which, of course, I don't agree with. It caused a very lively discussion.

The critics were mostly from the right?

Yes. They felt that the book was too pro-Palestinian, which is why I was somewhat surprised and amused to read the very critical review of the book in the Journal of Palestinian Studies. They really presented it as being too pro-Zionist.

What were their criticisms?

They claimed that it doesn't tell you enough about the sufferings of the Palestinians and doesn't take into account many Arab sources, which it really does. Basically, it was a political criticism, just as people in Israel had political or ideological remarks to make about the book -- those coming from the right, as you said. The idea that Israel really owes its existence to the British Empire is something that annoys many Israelis.

Why do you think it does?

Because we all grew up to believe that Israel was born out of a heroic struggle against the British oppressors, which was true for a very short period of time at the very end [of the British Mandate.] That is the collective memory and that is also what we learn in school. We don't really learn how supportive the British were of the Zionist movement from the very beginning. We also don't realize that the Zionist movement and Israel owe so much to British support. That comes as an unpleasant surprise to those people who were taught to study and remember our heroic struggle.

Has that been changed in Israeli schools?

Yes, many things have changed. You mentioned the new historians -- they are 15 years old by now. Things have filtered down into Israeli textbooks and through the media, books, newspaper articles and television. Textbooks today are much less mythological and ideological than they used to be.

Has that had a noticeable effect on the younger Israeli generations?

It is part of an overall process that is going on in Israel. That is the subject of another book which I published after "One Palestine, Complete": "The New Zionists." It describes recent developments in Israel, all of which seem to be leading us to something people call a "post-Zionist" situation. The new Zionists are part of that process. They are not the ones who instigate the changes; they are part of the changes.

We have a generation of Israelis today, especially people living in Tel Aviv and in places that look up to Tel Aviv, where people don't live for any ideology anymore. They don't live for the past or the future. They live for life itself and they live very much in the spirit of the American culture. They are much more open to realize, for example, that we share at least part of the responsibility for the creation of the Palestinian refugee situation and for the tragedy of 1948 [when 750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled during Israel's war for independence.] They are much more open to hearing that because the whole country is more open and pluralistic and less ideological. This is something that has happened particularly since Oslo [the 1993 peace accords between Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, which gave rise to great hope that peace might finally be at hand].

But since the present intifada began 14 months ago, we are being pushed back in time to tribal togetherness and closeness, which is really the major damage that we suffer as a result of terrorism. Of course, [we suffer] lost lives and tragedies. But in addition to that, what terrorism does to the fabric of the society, to the mentality and to the collective mood is perhaps even more damaging because it really stops that process [of becoming more open and pluralistic].

How much do you think the last 14 months will set Israel back in this way?

I'm not sure that I can answer that because I don't really know what the long-term effects of this intifada will be. The effect of the previous intifada [which started in late 1987 and waned in late 1991] was quite surprising. Israelis found a greater willingness to get rid of the war and the tension. The Palestinians learned from our willingness to enter into the Oslo Accords that Israelis only understand the language of force, something we only say about the Arabs. But there's no question that the first intifada is part of what led the Israelis to realize that it's not worth it.

In that sense we are very similar to the British. The British realized as early as 1939 that their role in Palestine was over.

Was that because of the Arab rebellion in 1936? (The Arab rebellion was a failed uprising against the British authorities and the Jews.)

Yes, three years of Arab terrorism. Not that the British weren't strong enough to put it down, to crush it. Eventually they did. But they asked themselves, "Is it worth it?" And, of course, Israelis could defeat the intifada of the 1980s -- we call it the "first" intifada when in reality the first intifada is the one of the 1930s -- but most Israelis thought that it wasn't worth it. Most Israelis said, "Why are we in Gaza? Let's get out of Gaza. Why are we in Jenin? Why are we in Hebron? Why are we in Jericho?" This is how Oslo was born.

I asked myself: How is it possible that all of a sudden so many Israelis realize that other things may be more worthwhile than chasing Palestinian kids in Gaza? This is when I realized that it's all part of the process of becoming less ideological, less nationalistic, more open, more pluralistic, more Americanized -- and more Jewish, in the sense of pluralism and openness to alternatives.

And now?

Now, we are all disillusioned and confused and very angry. So it's too early to say what the long-term effect will be.

And as some Israelis have gotten more open, the Palestinians have gotten more radical.

Yes, on both sides, it seems that the extremists are taking over. That is very tragic.

How much power do you think that Arafat has to stop the extremists on his side?

I can't answer that question. That is something that the CIA doesn't know, the Mossad doesn't know and Arafat himself probably doesn't know. I can only tell that it is not in the interest of Israel to encourage the downfall of Arafat. It is in the interest of Israel to strengthen Arafat and to make him regain whatever power he lost. And in order to do that, he needs something which he can show to his own people as representing some gains. The Palestinians have received no sign of hope from us.

There are several things which we can do. I don't believe that we can solve the conflict at this time. There's no solution to the conflict. But we can manage the conflict. By that I mean we can take a number of steps that will give the Palestinians some hope. It would be advisable to present these steps as something that Arafat has gained from his contact with Israel. Because so far, he's gained nothing.

What kind of steps?

We can unilaterally dismantle isolated settlements in Gaza. The Zionist dream will not suffer at all if these settlements are not there. They are increasing animosity, bitterness and violence. There's no reason for them to be there. We lose nothing if we agree to dismantle them. There are also small, isolated settlements on the West Bank, which we could dismantle without even beginning to try to solve the larger problem of the settlements.

One of the mistakes Barak made was that he tried to solve the conflict, rather than to manage it. Why was that a mistake? Because we don't have solutions to the big problems. We don't have a solution to the refugee problem right now, we don't have a solution to the settlement problem right now, we don't have a solution to the Jerusalem problem right now. These are the big problems that are hanging in the air between us and the Palestinians right now, but we can manage the conflict in a better way in order to reduce tension and in order to include more Palestinians in the peace process. The major mistake made during the Oslo process was that most Palestinians gained nothing from the whole process.

But many Israelis and American Jews believe that the Palestinians don't want peace with Israel -- and maybe that Arafat doesn't want peace with Israel -- and that they just want to see Israel destroyed. Do you think this might be true?

No, I don't see that this is the case. The Palestinians have made some very, very slow progress over many, many years. Eventually they have brought themselves to the point where they have made an agreement with Israel. We always praise the late Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin for shaking hands with Arafat and we say, "Wow, how difficult that was for him." Well, it was difficult for Arafat as well. Both sides have given up some of their basic positions, which is good. But we are still very, very far apart from each other.

How should Israel talk about Palestinian statehood?

It is in the interest of Israel to encourage Palestinian statehood. The Palestinians probably need a whole generation of statehood before they can reach the point which we have reached, where we were able to say to ourselves, "Our state is secure, our future is secure and we don't care to fight Palestinian kids anymore." But this is a realization you can make only after you have experienced a long period of statehood, having developed your own institutions and your own culture and made your own mistakes. Then at one point, you can say, well, there are other things that are worth more. Just as many Israelis realized that there are other things which are worth more than fighting Palestinians or holding on to the territories.

Is peace possible with Sharon as prime minister?

I don't see a possibility of peace either with Sharon or Arafat in power. For the simple reason that these are people whose whole lives have been spent fighting each other. People at 72 or 75 don't change all of a sudden. Sharon may be prevented from making war, but I don't think that he can be pushed into making peace.

Is there a desire in Sharon's administration to end the Palestinian Authority?

I don't know. He may be pragmatic enough to realize that it's better for Israel to maintain the Palestinian Authority. He may find himself in an automatic process that can't be stopped anymore. Things may get out of control. But if he really wanted to get rid of the Palestinian Authority and Arafat, he would have done so a long time ago without hesitation.

Why do you think Sharon decided to attack Arafat's compound? Was it just a political statement?

Because he has nothing else to do. That's what he does best. If he had suicide terrorists at his disposal, then your question would be justified. He doesn't have suicide terrorists to send to Arab towns. The only thing he has is the air force. That's what we know how to do. Destroying Arafat's helicopters is really an indication of helplessness, because what difference does it make? He will buy himself new helicopters or get them for free from some country. So what's the big deal? Also, this is the only thing we can bomb without killing civilians. We don't want to kill Arafat. The options are very limited, so that's what we do.

So do you blame Arafat for what has happened in recent weeks?

Of course I blame him for many things. Compare him to David Ben-Gurion under the British. David Ben-Gurion, for 30 years, worked on building a state. When the state was ready, he declared independence. Arafat is doing it the other way around. He's declaring independence but he has done nothing for his own people. There is nothing, no infrastructure, nothing. He is really only a war leader, and that is very tragic for the Palestinians. They have no leadership that really does something for the Palestinians. Arafat has built up an utterly corrupt and inefficient system with very frequent violations of human rights of his own people. A Palestinian prison is worse than an Israeli prison -- and an Israeli prison is bad enough for a Palestinian. There is no infrastructure of anything. And he had so many years to prepare it.

Did he have the money and support?

Since Oslo, he had all the money in the world. But instead of buying 50,000 computers, he bought 50,000 guns. Now he has a small oligarchy of people wearing uniforms and running around with weapons and he has no educational system and no medical system and no economic infrastructure. He blames all of it on Israel, and indeed Israel did not encourage him. The whole world did not lead him toward a positive direction and that is something which everybody shares the blame for. The world -- meaning the U.S. and Japan and Europe -- gave him enormous sums of money and they never told him what to do with it, probably part of the politically correct position that you do not tell someone what to do with his money. You don't want to be paternalistic. And so he wasted his money. The enthusiasm in the world immediately after Oslo was so enormous, as was the willingness of rich countries to pay for a Palestinian infrastructure. He wasted it all.

That's where I blame him. Not where he missed this or that opportunity, because I don't really know that he did. It's too easy to say, "Israel offered so much. You should have taken that."

Were you surprised when he rejected Barak's proposal?

Not really, because for one thing I never knew and I don't know now what it is we offered them.

Really? Why?

Everybody says something else. I felt then, and I feel even more strongly today, that the problems are too deep. I felt that it was wrong of Barak to go to Camp David and try to solve the problem. The problem has existed for the last 100 years and it can't be solved in a week at Camp David.

The pathetic thing about some of the people who participated in those talks, like Israeli Foreign Minister Shlomo Ben-Ami and [American negotiator] Dennis Ross, is that they now write books saying, "We were that close! Almost!" It's like the gambler: "I put another dollar on the table and I will get rich!" Well, it doesn't work that way.

It's so tragic because some people told Barak that it wouldn't work. At least one of them is very worth listening to because he's more experienced than everyone else: Shimon Peres. He told him, "Don't talk about the refugees, don't talk about Jerusalem, don't talk about the settlements. These are problems which we cannot solve. Talk about things which we can do now." This is what Oslo was all about -- about time, small steps over a very long period of time. But here comes Mr. Barak with his Napoleonic megalomania and says, "I will make peace." And so it all exploded. It's not only his fault. It's the nature of the subjects which came on the table. They don't have a solution.

Is the refugee problem the biggest concern?

Yes, because as long as being a refugee for so many people is not part of diplomatic history but an everyday reality, they cannot give up the hope to return to their homes. We have not yet created a distinction between the dream and their reality as refugees. Many of them live in camps where two people can't walk next to each other on the lane because the houses are so close to each other. The conditions are very, very poor there. That's an everyday reality for a third and fourth and fifth generation of refugees. And so naturally they can't accept anything less than a suggestion to return to their homes. Since that is impossible, we must realize that we don't have a solution to that problem at this time. So we need a lot of time.

Some people say if only the Palestinians had accepted the U.N. partition resolution of 1947 none of this would have happened.

The partition plan was not something that could work. The Zionist movement accepted it only because the Arabs rejected it. It was a diplomatically smart thing to do. Indeed, ever since those days we've used that smart move of 1947. The borders which this commission drew on a map could not have worked -- it left many Jews in the Arab state and it left 50,000 Arabs under Jewish control. It was just something you draw on a map. The principle was important, yes. But the Arabs had rejected an earlier partition plan of 1937 [the British Peel Commission plan, which awarded the Arabs far more territory than the U.N. plan, and which was also rejected by the Zionists] and the plan of 1947 was even worse. There was no way that they could accept it. If they had, we would still have war because these two countries wouldn't be able to live in the borders which the U.N. designed for them.

But from a diplomatic point of view, the Arabs made a mistake. They should have accepted it, just the way we did. But we did not accept it because we thought that was what was going to be -- we accepted it because we realized that it was the smart thing to do. Israelis knew that war was inevitable. They couldn't be sure that the Arabs would be defeated, but they knew that war was inevitable.

I ended up much more pessimistic when I ended the book than when I began. I began under the spirit of Oslo; I asked myself, "When was the last time that Jews and Arabs lived together? Under the British Mandate, so let's look at that because that's what we're trying to do now." By the time I finished the book, I reached the conclusion that the war of 1948 was inevitable, which unfortunately means that the Palestinian tragedy was inevitable.

Is this because Zionism and Arab nationalism were utterly incompatible?

Yes, I think so. The Arabs needed more time to realize that Zionism would prevail. As long as they had doubts about that, they objected. Some of them still do, but some don't. Surprise, surprise, we have a peace agreement with Egypt, which many people forget, but it's almost 25 years old. Surprise, surprise, we have a peace agreement with Jordan. The Jordanians gave up the West Bank -- things which in 1967 were inconceivable.

So to go back to whether the Palestinians want to destroy Israel or do not want peace -- they might not want it, but I think that they have realized that Israel is there to stay. They are really fighting, not against the existence of Israel, but for better conditions of independence, for the best they can get. They know they will get better conditions than they have now. Israel in fact supports the establishment of a Palestinian state; at least, 60 percent of Israelis do. The Palestinians know that they are really fighting for better conditions, but at present, their situation is very, very bad. Israeli oppression is very, very harsh. They really don't have any reason to tell themselves, "Let's concede something." They're getting harder.

And were their conditions always worse than the Zionists', even before independence?

Yes. Of course, their situation was much worse because they didn't have their own institutions, and mostly because the level of education was so low. This was a rural society and the British did not encourage them to develop their own education. After 30 years of British rule, seven out of 10 Palestinian kids didn't go to school, while practically all Jewish kids went to school. We really won 1948 as a result of our cultural and educational and technological superiority, rather than our military superiority.

Why did the Arabs have such a leadership problem then as well?

Because they are a very traditional society. It took them a very long time to get out of their very primitive, rural conditions and develop, even in the practical terms of communication between one village and the other, one city and another. Newspapers were useless for a long time because very few people could read them. They were organized around families rather than political parties. Their whole political development was very far from the Zionist development, which basically came from Europe and enjoyed the support of the British.

What role did terrorism play in pre-independence Palestine? How did that affect how long the British remained and how they regarded both Jews and Arabs?

Arab terrorism was more effective than Jewish terrorism. The Arabs fought against the British mostly and again, by 1939, the British realized that Palestine means trouble. They could have left in 1939 if it were not for World War II. The Jewish terrorist organizations, which acted mostly against the British, had some effect on the British. The British would have left without Jewish terrorism, but they had some effect. All these big headlines in the newspapers caused many people in England to write to their prime minister, letters which really sounded like things Israelis said in the '80s, namely: "Why is my son still in Gaza? Why is my son in Hebron? Why is my son in Jericho?"

Interestingly enough, David Ben-Gurion traveled to London and had long talks with Foreign Minister [Ernest] Bevin, pleading that the British stay on in Palestine. "Don't leave us now, because we are not ready for the real enemy which is not you, but the Arabs." This is a strange situation, where on the one hand some Jewish extremist organizations are acting against the British and the Zionist leadership is actually pleading with the British to stay.

It is, again, somewhat similar to the situation today. We are telling Arafat to stop terrorism. The British told David Ben-Gurion to stop terrorism. And David Ben-Gurion said, well, I wish I could. And Arafat is saying, well, I wish I could. In fact, if terrorism could be stopped, the British would have stopped it. If today's terrorism could be stopped, we would stop it. If these people could be arrested, as we require Arafat to arrest them, we would arrest them ourselves. If we could prevent terrorism as we've demanded Arafat prevent it, we would prevent it ourselves. Obviously, we can't. And he can't.

Was there a moment during British control when an opportunity arose for the two sides to come together?

I don't really think so. One of the things especially leftist people in Israel do is constantly ask themselves, Where did we go wrong? What mistakes did we make? They come up with all kinds of answers: We could have been nicer to the Arabs, maybe we should have all learned Arabic, maybe we could have been more open to Arab culture. But these are all minor things. Yes, here and there we made mistakes. But basically this is an inevitable conflict. The Arabs didn't want us there. And they have a very, very hard time realizing that we are there to stay. At least in that, the Zionist leadership was right when they said we need to be strong and convince the Arabs that we are here forever.

That was the right Zionist position to take, that is the Israeli position today. The question is, of course, what makes us strong? Some people believe that we will be stronger if we pull back from the occupied territories and I definitely think so. I don't regard them as a source of strength, I regard them as a source of trouble.

What do Israelis think about the occupied territories?

After 35 years of occupation, most Israelis don't regard most of the territories as part of Israel. This is really interesting. Many of the settlers don't regard their own settlement as part of Israel. To ask settlers where they bury their dead -- if they bury their dead there, where they live, then that's a sign that they feel at home there and are there to stay. But many of them bring their dead to Israel. Because they know that eventually they will not be able to stay there forever.

Also, tragically, many Israelis feel stronger about people who get killed by terrorist actions inside Israel than for people who get killed on the settlements. It's a very clear distinction they make. They don't even regard Arab East Jerusalem as part of Israel. Israelis don't go there.

What should the U.S. role be? You must not have agreed with Clinton's role at Camp David.

Obviously, the U.S. was part of that mistake, of Camp David. Just as Barak was at the end of his term in office, also Clinton was at the very end of the term in office. It was really like a gambler whose wife is standing at the door of the casino and says, "OK, you have five minutes more. And then we go home."

Basically, without the U.S. we cannot ever get talks rolling again. We really need the U.S. intervention in the process. These are two sides who don't talk to each other right now, so you need a marriage counselor. The first Bush months were really very harmful to the situation, when he pretended that he could just ignore the Middle East. Now he has sent us somebody who is new to the conflict, but I understand that he is learning fast because wherever he stays, something blows up outside his hotel. I hope that the U.S. will play an active role in getting us and the Palestinians to talk.

What's the first thing that needs to happen?

The first thing is to reduce terrorism. I don't go for these ultimatums of seven days or six days or five days of complete lack of violence. You can talk to your enemy even if your enemy shoots at you, because otherwise he wouldn't be your enemy. The very fact that we have terrorism is not something that should prevent us from talking. It's a question of the level of terrorism -- that has to be reduced. Also, for political reasons, it's just impossible for an Israeli government to go and sit and talk to the Palestinians when 25 teenagers get blown up in Jerusalem and Haifa. The same is true for the Palestinians. If we kill some Palestinian boys and girls, then the Palestinian leadership can't sit down and talk to us as if nothing has happened. There's a very strong level of emotion here. That would be the first step.

The second step would be to ease the closure on Palestinian towns and villages and let more Palestinians work in Israel and ease the freedom of movement. Make life a little bit less miserable for the Palestinians. And it would be a very easy thing to dismantle the settlements. That would at least give the Palestinians some kind of hope. Then, we'll see what happens next. Nothing should be done fast, except reduction of terrorism and making life easier for Palestinians. These are the two acute problems.

Shares