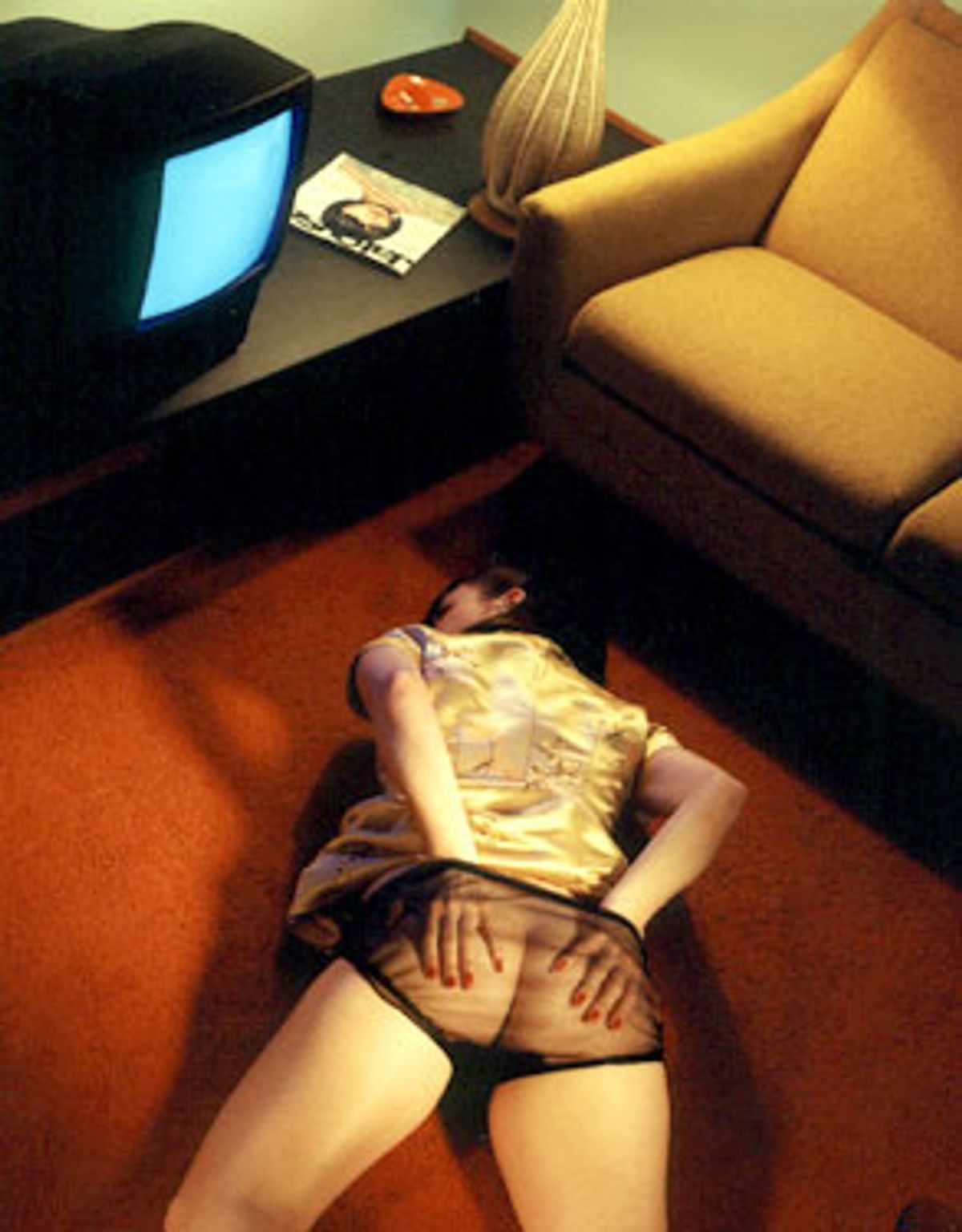

At the Bambi Motel in Columbus, Ohio, an alluring, nearly naked redhead lies sprawled on the floor of one of the lodging's dimly lit, slightly raffish rooms. She's on her back, dressed only in diaphanous white panties and black Mary Janes, and her eyes appear closed. She could be dead, sleeping or simply posing for an erotic photograph. The viewer alone determines if this is a crime scene torn from the pages of a Jim Thompson novella or something a tad less sinister.

There are other rooms, other assignations and situations. On a wine-colored couch, circa 1960, a topless brunet in mules and sheer dark knickers is involved in various spiderlike contortions. Who is she doing this for and why, one wonders? More puzzling are the chambers where a touch of the surreal is introduced: like the backside of a woman decked out in vintage garters and high heels, severed from its upper half by the folds of a dull gold curtain falling over a vermilion rug. Perhaps the head and arms of this inviting posterior are hidden by the hanging fabric. Or maybe the rest of her has vanished into some parallel Lynchean universe.

The Bambi is not the only repository of such neo-noir visual poetics. Nearby, there's the Brookside, Motel One, the Homestead and others. It's a realm of half-full ashtrays, shot glasses brimming with bourbon and dames in horn-rims and bullet bras.

This sexually charged alternate universe is the purview of Ohio photographer Chas Ray Krider, who refers to his adult fantasyland simply as "motel fetish." For the past five years, he's explored this lamplit twilight zone in spreads for erotic magazines like Taboo, Libido and Leg World as well as for book compilations such as "Love, Lust, Desire," "Femmes" and "The Mammoth Book of Illustrated Erotica."

Krider's creations, which he also produces for the amusement of himself and his collectors, sweat lounge-era exotica from every pore, transforming the otherwise mundane atmospherics of dusty motor inns into scenes echoing the work of Edward Hopper or Alfred Hitchcock. Imbued with warm, rich reds, greens and yellows and accented with décor from a bygone era, Krider's vignettes reflect an imagination molded by a town such as Columbus -- a town that, similar to other parts of Middle America, retains an odd "Peyton Place" feel to it.

Like Krider's enticing, blank-faced models, these Columbus motel rooms seem trapped in amber and only lightly touched, if at all, by more recent conveniences and fashions.

"I'm drawing on my precognizant view of life -- that kind of '60s square life," explains Krider, who declines to give his age. "In high school, I worked in a record store, and I was interested in the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. But we sold tons of this easy-listening stuff. It was crap, I thought. I'd hear it all day long. I'd be so bored, I'd be flipping through the album bins, looking at these easy-listening album covers that have the most fantastic photographs on them. Very sexy, very seductive imagery. Today I find all of that precognizant input much more interesting and worth exploring. So when I go to a motel, I have in my mind a place where you could have a sexual encounter that's neither pornographic nor that Sports Illustrated swimsuit mentality that we have today."

Though Krider finds most of his motel room settings in Columbus, where the near-retro interior comes complete with the low daily rate, he does occasionally have to create or tweak the atmosphere to get the look he requires. If there's a model in another city he wants, or if he's doing commissioned work in Los Angeles, he travels knowing that the ingredients for his particular aesthetic recipe will be readily available.

"One day in L.A., we scouted 30 motel locations, and they all sucked. So I picked one, and I went to the thrift stores and bought some cheap carpet and some bad furniture and built a set. I can put in the kind of color, ambiance and the right forms I need. On location, it's hard to find motels that haven't been redecorated in the '80s when you end up with something like a Southwestern, mauve theme," he says.

Krider says he's not trying to re-create any particular period, but rather a timeless quality based on memories of his youth. Sometimes he'll even throw in an anachronism like a CD walkman to disrupt the idea that he's manufacturing a sort of diorama of Kennedy-era leisure culture. His models often mirror this odd mixture of decades, sometimes wearing a girdle or see-through panties that Krider has salvaged from vintage clothes outlets, and matching them with their own shoes from the present and perhaps a recent bra from Victoria's Secret.

The result is a time-warp that, in light of the ongoing interest in retro-lounge culture by young adults, creates certain visual conundrums. Take one photo of a woman's legs and hips: She wears white undies, a black pump on one foot and the other bare save for beige nylons. Her velvet-gloved arm rests provocatively on her groin, and two cocktails sit on the floor before her. The image could double as cover art for novels by Raymond Chandler and Haruki Murakami.

Another of a woman standing next to a dated table lamp set on the floor, her hands tied by what looks like a black electrical cord might be a still from "Blue Velvet," or an interpretation of some classic Irving Klaw bondage pic.

"Most of the things in my motels are really '70s and early '80s furniture and props," Krider says. "But my whole sense of color really throws it back. People will always say it's the 1950s. That's maybe because it has what I call the warmth of the past. Also, my use of light and shadow is very film noir."

Krider's work contradicts the concept that everything interesting and original comes out of New York or L.A. Though Krider has 20 years of experience with fine art photography, much of it invested with the phycho-sexual tension of his "Motel Fetish" compositions, he is largely self-taught, having graduated from Ohio State with no specific major. He's lived most of his life in Columbus, leaving only for a bit of hitchhiking after college.

And with the exception of some models like the inimitable Dita von Tease, who lives elsewhere and has her own following, most of Krider's ladies are homegrown nonprofessionals with far from perfect bodies (as judged by Hollywood standards). These women, attractive yet somewhat ordinary, lend Krider's compositions authenticity, and help sustain that suspension of disbelief provoked by the narrative aspect of the photos.

"I became an artist because I was interested in art as a vehicle through time and space," he says. "Everyone's actions should take them to a state of higher consciousness. The motel work for me is a kind of tantric yoga exercise. I'm taking these low sexual energies, and slowly, methodically moving them up to a higher plane. Basically, I'm building a still life, and the model is one part of that. Eventually she gets to her lowest emotional level, her true self. They just sink into this nothingness they're in."

What becomes frozen in time is "that moment when you have the anticipation you're going to have this sexual fling," says Krider. There's also the potential for violence, perhaps even what the Germans call lustmord, or lust murder. And if Krider occasionally shows us what might be the pause after the storm, it might also be the stillness following homicide, with the killer outside the frame.

Krider is paused before a storm of sorts, having recently signed an agreement with Taschen for a motel fetish book due in October of this year. Though he dreams of having a film based on his art and directed by, of course, David Lynch, Krider probably won't leave Columbus anytime soon. He seems a very precise individual, one who wants to be in total control of his environment and destiny. Columbus is the perfect setting for that.

"I'm living this strange motel-gothic existence," he says. "You couldn't do this thing in L.A. without getting into the industry and being part of the business. Here, it's a completely fabricated kind of existence, because life here is that uninteresting. So you've got to go down deep inside to make a more rich environment."

Shares