In nominating and awarding the Oscars for best actor and actress, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences doesn't always fall for the showiest, most mannered performances. Just most of the time.

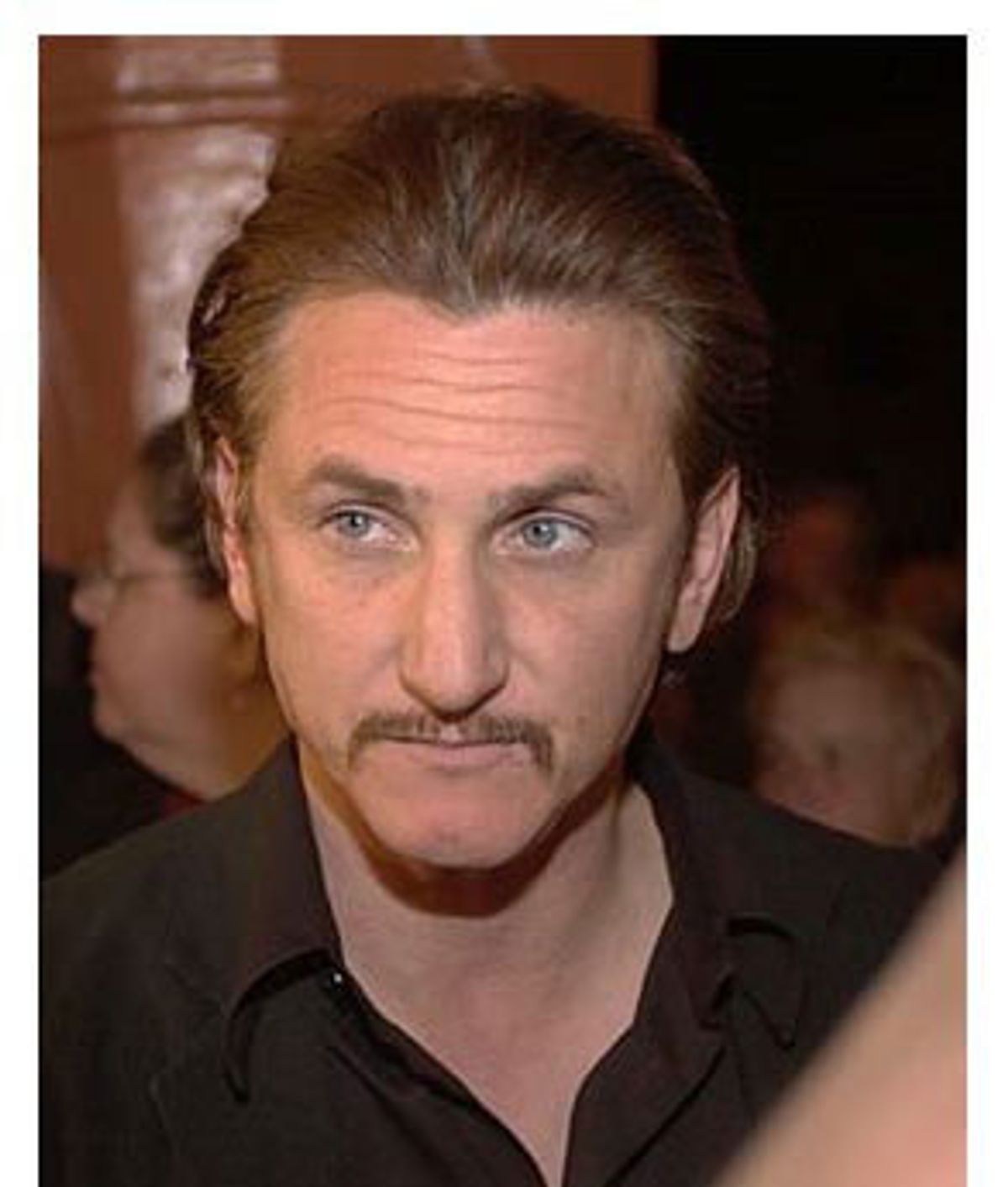

Sean Penn was nominated in 1995 for his role as death-row killer Matthew Poncelet in "Dead Man Walking," a characteristically understated, and astonishing, performance. Now he's nominated again for his role as a mentally retarded man who fights for custody of his young daughter in "I Am Sam." Forced, stuntlike and repetitiously punctuated with elfin grimaces and sunshine-innocent beaming, it may very well be his worst performance.

The occasion of one bad performance may seem like a strange time to celebrate an actor's career. But then, there's some truth to the adage that you often don't know how much you love something until you have, at least temporarily, lost it. Penn's contemporaries (people like Tim Robbins, who directed him in "Dead Man Walking") and his elders (the actors he looked up to in his youth and who later became his friends, among them Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson) have cited him as the finest actor of his generation. Although I'd have a hard time deciding between Penn and Robert Downey Jr., I'd still say they're pretty close to right.

But Penn has continually threatened to quit acting, and although he always comes back, you can't blame him for being as disillusioned as he is -- not with acting itself, necessarily, but with the nasty business of acting. "It's a bad time for acting," Penn said in a 1998 interview with the New York Times Magazine, just as he was completing Woody Allen's "Sweet and Lowdown." Movies break down into the expressive and the impressive. And the impressive has pretty well taken over the box office. The thing film actors of my generation are most afraid of is being found out to be a fraud. Even the ones that aren't frauds think they are. That's why so many people succumb to a mass embrace. It makes them feel protected against the anxiety that they may not have anything to share. Some of them do have something to share, but they've given it up."

Of course, no one expects Penn to go away overnight as an actor: His distrust with Hollywood games is as much a part of him as the dimple in his chin, and it's most likely the thing that's guided him straight all these years. But he works so infrequently these days that seeing him in a bad role only makes you long to see him at his best.

Penn's best is different for every moviegoer. It isn't so much that Penn is different in every role. It's the different kinds of different that he comes up with -- the subtle variations on even a stock character that he pulls from his own mysterious depths. His characters are rarely static; two roles in particular are miracles of transformation. As Sgt. Tony Meserve in "Casualties of War" (1989) and as coked-up mob lawyer Davey Kleinfeld in "Carlito's Way" (1993), both directed by Brian De Palma, Penn runs off with us before he has even fully won us over. Watching his face at the end of each movie, we can't be sure if he's the same person we met at the beginning. The more we think about it, the more we realize he's not, and yet there we are with him anyway. In his best performances, he takes us as willing hostages.

The great secret of Penn's skill may be that he's not an easy actor to like. His face doesn't win us over immediately, the way, say, Matt Dillon's or Jim Carrey's or Jeff Bridges' does. At the beginning of each new performance, he seems like a stranger, someone we have to get to know even though he seems vaguely (or overtly) determined to keep us out. His eyes can be small, hard, dark and unforgiving, which is what makes their radiant openness, when we catch it, so affecting. His mouth is anything but sensual and expressive: It's a hyphen of a mouth that catches you by surprise when it stretches into a wide, pumpkin-carved smile.

He falls into the category that a character in the recent romantic comedy "Kissing Jessica Stein" refers to as "sexy-ugly." The sexy-ugly guy is one who works on you in spite of yourself, who shows up unbidden in your erotic dreams not because you want him there but simply because he's asserting his right to be there. In Penn's case, that's often true from scene to scene, even if we're not talking about performances that are particularly erotic.

In "Dead Man Walking," his Matthew Poncelet is such a closed-off and unyielding character that it's almost difficult to look at him in his earliest scenes, with his arrogant pompadour and BB-size eyes. Penn's Poncelet wins us over only by making us unable to look away. He never rounds off the hard edges of this character, not even in Poncelet's last-ditch moment of redemption. His performance consists of a repeated and minute chipping away at those edges, the flakes flying off them like bright, tiny sparks. No wonder we can't take our eyes off him.

As Meserve in "Casualties," we see a different type of transformation. Dutiful and tough, he's the Army's most valuable type of soldier, not because he spouts patriotic crap but because he's devoted to keeping his men alive. But when he loses one of them, his closest friend, he begins to shut down, and like no other actor I can recall, Penn lays it out for us in chilling, subtle detail. After a bloody surprise attack, we see him and his men back at their base. The men, Michael J. Fox among them, laugh and joke on their bunks in the background; their patter is supposedly the focus of the scene, but De Palma shows us Meserve in the right foreground of the frame, silently and meticulously shaving as if he were a science-fiction monster scraping his old face away. He's all we can look at. When the men ask him what he's going to do with his few hours of free time before their next assignment, he announces with robotic heartiness that he's going into town to get himself a whore.

No sooner has the line come out of his mouth than his face, now shaven clean, resumes its eerie emptiness -- Meserve, the good man who'd do anything for his men, is draining away by the second before our very eyes. It's one of the most horrifying performances put on screen, mostly because even as Penn's Meserve distances himself from us so coldly, there's something inside him that seems to beg us to clutch out and grab him. That mirror is a maw, and it eats him whole as we watch.

When an interviewer asked Penn's "Casualties" costar Michael J. Fox what it was like to meet Sean Penn, Fox replied that he hadn't met Penn; he'd met Meserve. Penn may not consider himself a method actor, but he's method in the truest sense: He invites a character to burrow deep inside and then dares it to eat its way out of him.

In his book "A Pound of Flesh: Perilous Tales of How to Produce Movies in Hollywood," producer Art Linson writes about casting -- or, more aptly, almost not casting -- Penn in the 1982 "Fast Times at Ridgemont High." When Penn came in to read for the role of Jeff Spicoli," Linson writes, "he stammered, he flopped around like a beached carp, was barely audible, turned red and said, 'I really don't like to read.'"

For no good discernible reason, Linson and the movie's director, Amy Heckerling, knew they had to cast Penn. "There was something about him! We jumped in blind, and to this day I can't seem to articulate exactly what it was," Linson writes.

Penn showed up to shoot the film having not so much researched his surfer-burnout role as inhaled it. His scenes with the late Ray Walston, who plays persnickety history teacher Mr. Hand, are among the most memorable in the movie. They spar like a romantic-comedy duo. When Walston asks Penn crisply why he's consistently late for class, he waits one slow beat, then two, then three, and then the answer slips confidently through his clueless "O" of a mouth: "I don't know."

Penn slips so completely into his roles that he's sometimes almost unrecognizable. When he first shows up as Davey Kleinfeld in "Carlito's Way," with his frizzy reddish hair and gogglish wire-rimmed glasses, he seems to be reveling in the effectiveness of his nebbish disguise, like a kid who's fooled his own parents with his Halloween costume. But Penn takes the role to its furthest limits. As he did with Meserve, he shows us Kleinfeld's transformation from gangly, corrupt bookishness to unhinged paranoia by not showing it to us at all: It's all written within parentheses on his face, implied but never spoken.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

There are plenty of parentheses in Penn's performance in "I Am Sam," which is precisely the problem with it. It's a performance written in calculated pauses, affected stammering and timed-just-right rolling of the eyes -- punctuation as performance. It's not solely Penn's fault that the movie is as bad as it is (I assign most of the blame to writer-director Jessie Nelson and her co-writer Kristine Johnson for creating the moist, gooey, hospitable atmosphere in which a fungus like this can grow), but he's certainly an accessory to the crime. Almost every frame of "I Am Sam" makes a booming demand that's falsely disguised as a gentle, searching question: "How can you not love this sweet, simple man and his perky moppet of a daughter?"

Those of us who hate the movie have been accused of everything from callousness toward the mentally impaired to outright heartlessness. But I think there are plenty of moviegoers who would, if the movie weren't about a mentally retarded man, turn away from the garishness of its emotion. Penn works hard in "I Am Sam," and it shows; it's the kind of role an actor takes in order to prove himself. And for that reason, it's a bit surprising that Penn should have taken it in the first place. He's the last guy I'd peg as a sucker for the picture's mucky "All you need is love" ethos.

I suffered through every moment of Penn's performance in "I Am Sam." But no matter how much I dislike it, it will never quell my love for Penn in movies like the 1983 "Bad Boys" or 1997's "She's So Lovely." Directed by Nick Cassavetes, "She's So Lovely" is a clattery, clunky picture that's deeply in love with its own color-by-numbers dissoluteness. But Penn, who plays a weirdly intelligent but mentally unbalanced man who loses his wife to another, keeps its heartbeat kicking.

Penn's wife is played by his real-life wife, Robin Wright-Penn, who is normally a fine actress but who over-emotes embarrassingly here. Nevertheless, his tenderness and delicacy with her are extraordinary to watch. "We were meant for each other, we're all banged up," he says gently, leading her to bed after he too is beaten up by their beefy bully of a neighbor (James Gandolfini). Unlike his Sam in "I Am Sam," Penn's character in "She's So Lovely" is simple-minded without being simple. And it's as gentle and moving a performance as I've seen him give.

It also fulfills all the promise Penn showed in one of his earliest roles. In Rick Rosenthal's "Bad Boys," Penn plays a hard-edged, reckless juvenile criminal who's locked up for his involvement in the accidental death of a neighborhood boy. The movie is good only in a good-bad sort of way -- it's a direct descendant of old-time juvenile delinquent movies, updated only with modern violence and bloodiness.

But Penn's virtually silent performance carves its way so deeply into the movie that you barely notice how corny the story is. Penn knew even then that to show us anything as cheap as outright pain or anguish or fear was a way of undermining our own capacity for understanding. Instead, he simply trusted us to get it, and we did.

Why would an actor capable of such magnificent subtlety even take on a role as numbingly one-note as Penn's in "I Am Sam?" Its obvious challenges aside, I wonder if, unwittingly, he felt the need to take on a role that he thought most audiences would be likely to get. Every actor needs to be understood, and Penn, his resolute independence notwithstanding, can't possibly be an exception. His role in "I Am Sam" may be the first time he has asked us outright to love him. Now that he knows we do, maybe he'll go back to trusting us, as he seemed to before, to listen closely to him even when he's saying nothing.

Shares