As we walk though Central Park, James Toback tells me a true story that sounds more like a scene from a movie. It's about a pedophile, accused of sleeping with boys, on the run from the police and $10,000 in debt to a bookie, who has just shown up at Toback's hotel room door begging for the money. Suddenly, Toback's voice begins to trail off. Something has caught his eye. He grabs my forearm; we stop walking.

"Come over here," he says. "I want to show you something. This is an example of how I get a bad reputation."

With his hands on my shoulders, he focuses me on a woman with long blond hair who is reading cross-legged on a blanket in the middle of the Great Lawn. "This is what I do," he whispers as we head toward her, "I see this girl, and she looks like she may be interesting. And as I get closer and closer I see if she still holds my attention. I see if there's a gravitational pull; because if there isn't, what's the fucking point?"

But we walk past her. He pans his arm from left to right across the skyline of trees that surround Central Park, This shot could be an establishing scene.

Then we actually turn back and walk up to her. His hand is on my back, guiding us toward her, and I'm nervous, scrambling for something to say. But he takes the lead, and as he approaches her he says, "Excuse me. I wonder. Have you ever done, or would you be interested in doing, anything cinematic? And if you are, would you be interested in discussing it?" Squinting her eyes in confusion and blushing, she asks what he means.

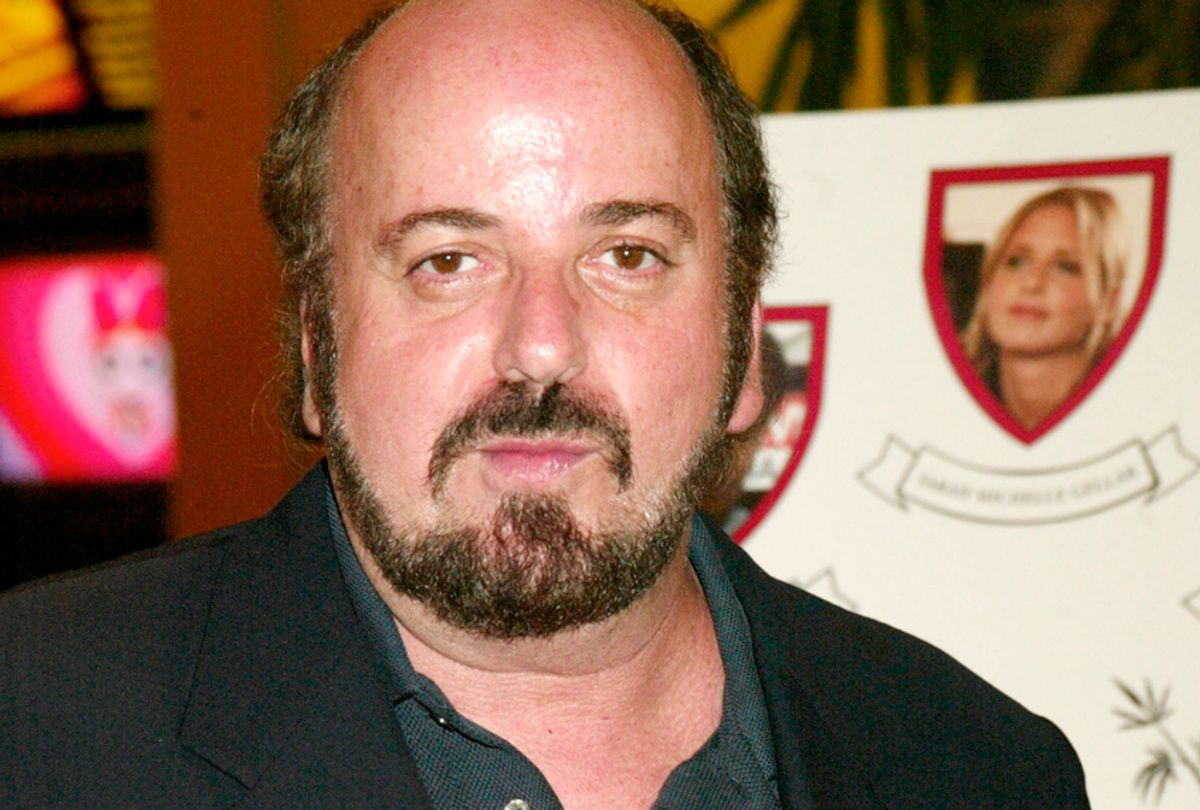

"My name's James Toback," he smiles as he shakes her hand. "I'm a movie director. Have you ever seen 'Black and White' or 'Two Girls and a Guy' or 'The Pick-Up Artist'?" She shakes her head no.

So he jokes, "You're under arrest," and turns the conversation to her. "Are you a student? What are you majoring in? Did you vote for her for Senate?" he asks, pointing to the Clinton for Senate flier in her lap. He's captivated her. She plays with her hair and beams up at the bearded, balding man who might put her name in bright lights.

He's as charming as Robert Downey Jr.'s character in "The Pick-Up Artist" (1987), the compulsive womanizer who combs the Upper West Side for candidates and justifies his behavior by saying, "I have a vested interest in meeting strangers. Every woman that I've ever liked or communed with or given great satisfaction to always started off as a stranger."

The girl has forgotten that Toback is a stranger. He interrupts her giggles and goings-on about voting for Clinton. "Check out my work," he says. "If you see anything you think you connect with and might want to be a part of -- without promising anything -- call me."

A one-of-a-kind-opportunity smile forms on her face, she hands him her flier and he writes his number on it. As she thanks him, we turn away and he says, "I do that 15 times a week. Well, OK, maybe 50 times a week. Forty girls and 10 guys."

Toback's routine reveals how life is a laboratory for his films. The director brazenly puts himself in dicey situations and then bases his films on the resulting risks and consequences. Of the nine movies he has written and directed, all are autobiographical to some extent. Just as "The Pick-Up Artist" reflects Toback's personality, so do the rest of his films.

"The idea is not to have a separation between my life and my movies," Toback says. The claim is not a novel one but seems especially interesting in his case. By leading a hopelessly theatrical life, he has found the fodder for nine films. He's an East Coast guy with West Coast connections who, like Orson Welles, demonstrates the creative uses of his theatrical extravagances.

Although Toback's obsessive lifestyle has created obstacles for him, it has also provided the formula for his filmmaking. With the release of his last film, "Black and White" (1999), Toback "[threw] down a challenge to every other filmmaker working in this country," proclaimed Film Journal. Now, at 57 and married for the second time, Toback is releasing "Harvard Man," which opened last week in New York and should reach other cities soon. It's a movie he's talked about making for more than a decade. His most autobiographical yet, it seems to encapsulate all his gambles.

Ask anyone in the film industry about Toback, and his less discreet days of '70s excess as a gambler, partygoer and womanizer are sure to arise. His libido was so legendary that in 1989 Spy magazine published an eight-page foldout chart of his exploits called "The Pick-Up Artist's Guide to Picking Up Women."

But Toback never concealed his behavior; he flaunted it. He even wrote a book, "Jim" (1971), an admittedly self-centered biography of football legend Jim Brown that chronicles Toback's experience as a Jewish white guy who lived with Brown in Hollywood, a life that was essentially a series of wild parties and orgies: "Jim [Brown] is making his rounds ... Jane Fonda is there and Sharon Tate ... I drift into an old friend, a delicate girl of angled, Nordic beauty ... and embark with her on an orgy ... Jim joins."

The book includes tidbits of advice, like Warren Beatty's supposed suggestion to include a small part for a pretty young actress in every motion picture and to schedule auditions for that part late in the day. Indeed, Toback's films include a troupe of pretty young women, from unknowns to recognized actresses like Nastassja Kinski ("Exposed," 1983), Heather Graham ("Two Girls and a Guy," 1997), Claudia Schiffer ("Black and White," 1999) and Sarah Michelle Gellar, who stars in "Harvard Man."

In Toback's new film, sex, gambling, madness and drugs converge in a story loosely based on his college days at Harvard (class of 1966). Adrian Grenier stars as Alan Jensen, a philosophy student and the star of Harvard's basketball team, lured by his girlfriend and Mafia princess Cindy Bandolini (Gellar) to fix the team's game against Yale. But before the big game Alan drops LSD and winds up tripping for eight days. Soon the FBI and the Mafia are after him and his solution is to seek refuge in the arms of his sexy, bisexual philosophy teacher.

Toback sees "Harvard Man" as a complete fulfillment of his vision. "It is the first movie that really makes madness felt," says Toback. "You get the sense of the hallucinatory beauty of it," he adds, referring to the digital-effects-laden scene of Alan's trip. "It's both the ecstasy and excruciating pain of death." It includes what he describes as his favorite hallucination: seeing a nude woman walk out of a Gauguin painting.

We've almost made it to the west side of Central Park, a place Toback says he visits every day. His pace is surprisingly quick; he swerves from path to path knowingly. Near a reservoir he points left to a minicanyon of rocks and twisted trees where the opening scene of "Black and White" was filmed. But the scene is memorable more for its sex than the landscape. It opens to the beat of the Stylistics' '70s hit "Daddy's Little Girl," and the camera pans to a ménage à trois featuring two young girls and a black gangster pressed up against a tree while another black man looks on. Though the copulating trio is mostly clothed, it is incredibly suggestive, even after the three cuts necessary to get an R rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA).

Sex has always been one of Toback's favorite subjects, especially when it's raw and unadulterated. He favors direct, explicit sexual depiction over watered-down anesthetized scenes because, he says, sexual obsession and sexual duplicity are ignored in American movies today. The director doesn't want to make NC-17 movies (many theater chains won't show them and many newspapers won't advertise them). He knows that an R rating is more marketable, but insists there's a purpose behind his explicit material.

"The whole idea of a sex scene," Toback told Charlie Rose in a 1998 TV interview, "is that it be a scene in which characters reveal themselves by the specifics of their behavior. If it's worth making a movie about these characters, it's worth understanding their sexual nature."

But the MPAA hasn't seen his reasoning, and his movies are notorious for necessitating multiple submissions to the MPAA appeals board. The first film Toback wrote and directed, "Fingers" (1978), starred Harvey Keitel as a would-be concert pianist who is also a debt collector for the Mob. It was edited 13 times before the MPAA reclassified it from an X rating to an R. The release of "Two Girls and a Guy" was delayed because of an eight-minute scene between Robert Downey Jr. and Heather Graham. Though both actors are clothed, the scene was edited and reedited almost 10 times before the association removed the NC-17 rating.

According to the MPAA, ratings are assigned based on what parents would consider an appropriate rating. Its ratings board, an anonymous group of Los Angeles-area parents, takes into account how the elements of theme, violence, language, nudity, sensuality and drug abuse are dealt with on-screen. MPAA policy is that a rating can only be based on what is seen, not what may be implied, suggested, imagined or thought.

As a result, Toback's films display carefully edited sex scenes that remain shocking and remarkably effective. Roger Ebert wrote in a review of "Exposed" (1983) that a scene in which Rudolf Nureyev seduces Nastassja Kinski with a violin bow made him "realize how many barriers sometimes exist between a performance and an audience. Here there are none."

On a cold night last November, Toback and I agree to meet for dinner at an Upper East Side sushi bar. He calls twice to say he'll be late. When he finally arrives, the owner is locking the front door. After apologizing, Toback explains he has been finagling the financing for "Harvard Man" and he hasn't eaten all day. He's casually dressed in a basketball warm-up suit, black "Harvard Man" hat and gold chain. He seems wound up. There are beads of sweat on his forehead and he can't stand still. We practically run to a bistro a block away, which he decides against on the off chance we might run into someone he doesn't want to see.

He decides on Elaine's restaurant, a short cab ride away, when a good-looking young black man hops out of a Honda with shiny hubcaps parked at the curb. It's Oli "Power" Grant of the Wu-Tang Clan, who was in "Black and White." Early in the movie Power has a voice-over that captures the questions of identity the film poses. He asks, "Can you change who you are? Do you love the other more than you love yourself? Do you wish you were another way? If you're black can you bleach? If you're white can you dye?"

Power bounds over, leaving the car pumping with bass, and he and Toback shake hands, patting each other on the back. "What's been goin' on, man?" Power asks, rubbing his chin. "I've been trying to call you, but I can't find your number. I got something I want you to check out."

Toback rattles off the number he gave the girl in the park, and the hip-hop mogul punches it into his cellphone memory. There's a cab down the street; Toback hails it, saying he's late for dinner. The two shake hands, snapping their fingers together at the end, and agree to talk in the next couple of days.

We ride four blocks and Toback jumps out of the cab at a stoplight on 92nd Street and passes a wad of cash to the driver. But the restaurant is still five blocks away. When he realizes the mistake he asks himself what the hell he's doing, and we hustle the rest of the way to Elaine's.

The restaurant's namesake, Elaine Kaufman, was in "The Big Bang," Toback's 1989 documentary about the creation of the universe. The film employs Toback's idea that the cosmos began with the orgasmic explosion of God. He lets a diverse group of people, ranging from Kaufman and astronomer Fred Hess to a 7-year-old girl and basketball star Darryl Dawkins, express their theories on how it all began.

Besides God and sex they talk about other issues, like crime, madness and death. Answers range from the girl's theory on the beginning of the universe ("First there was dust, then there was a squirrel, then there was a dog, then there was a cat") to Dawkins' view of his own sex appeal: "I'm 6 foot 11 inches of steel and sex appeal and I try to live up to that." As we enter the restaurant, the maitre d' greets Toback warmly and whisks us into the back room and away from the crowd waiting for tables.

The back room is full. There is a cast party for HBO's "Sex and the City "in the corner guzzling wine, waiting for food to arrive. When the waiter arrives at our table, Toback orders a plate of pasta marinara with "extra, extra" parmesan cheese and a mineral water. I ask him if he ever drinks alcohol. He never does anymore, he says. No alcohol, no cigarettes and no drugs.

The last time Toback took LSD was "the biggest dose ever," he tells me, and it ended his drug career. At 19, in college at Harvard, he tripped for eight days: one day of ecstasy and seven days of madness. He remembers wanting to kill himself but didn't because he thought, "What if I feel like this after I'm dead? Then I can't even have the spiritual fantasy that death is going to end this agony." He says the trip didn't end until he was given an intravenous antidote devised by Max Rinkel, the German doctor who synthesized LSD in Switzerland with Albert Hoffman almost a century ago.

Besides drugs, another addiction that Toback has given up, at least publicly, is gambling. Years of gambling supplied Toback with the creative material for a series of films: After writing the screenplay for Karel Reisz's "The Gambler" in 1974, he wrote and directed "Fingers" (1978), "Love and Money" (1982), "Exposed" (1983) and "The Pick-Up Artist" (1987). All include characters who gamble, and not just with money, says Toback. They deal with obsessive, extreme forms of projection of the self, the forging of the self and the loss of self.

His screenplay for "Bugsy," Warren Beatty's movie about the Hollywood gangster who dreamed up Las Vegas, received an Oscar nomination in 1991. Today Toback concludes: "If you've seen all of my movies, I don't think you ever need to see anything else or hear anything else about gambling, because it's all in one movie or another. They say everything there is to know about gambling, not just from my point of view but from anyone's."

After "The Big Bang," Toback began to experiment with his filmmaking by gradually allowing more and more improvisation. His love for that kind of creative immediacy has meant tinkering with his control as a director. In "Black and White," he offers a medley of people who interact in a mix of improvised and scripted scenes. "It gave the actors the opportunity to display and be observed in the process," says Toback. "It was as if the film and life were going on simultaneously."

But to people who worked on the set with Toback it was a wild ride. David Ferrara, cinematographer of "Harvard Man" and "Black and White," remembers a situation set up by Toback in the latter film that shocked everyone on the set and demonstrated the director's ability to elicit performances by creating situations with unforeseen ends. In the film, Robert Downey Jr. plays Terry, an irrepressible gay man who hits on nearly every man he meets. Terry approaches convicted felon Mike Tyson (playing himself) at a party.

Tyson is standing by a window having a private moment when Downey walks up, nervous and excited to be in the presence of such a famous and violent man. "My heart is pounding," he tells the boxer. "I'm all fluttery, and if I seem strange, I'm sorry."

Tyson interrupts him to warn: "I'm on parole, brother, please."

Downey persists, eyes batting: "I had a dream about you. And in the dream you were holding me." Tyson's rage-filled reaction is real as he smacks and strangles Downey to the ground.

"It stunned me, I had no idea what was going to happen," Ferrara remembers. "I kept filming, but my heart was racing because I couldn't tell how serious the scene was. I didn't know if Mike was really hurting him."

As we leave the restaurant, Toback holds the door for two women, and once outside, he notices a woman bending over a stroller handing a bottle to her baby. He pauses to comment on the baby's cute chubby cheeks. "May I steal him? Can I eat his face?" he teases. "How can you possibly not eat his cheeks? Look at his face. How do you survive with cheeks like that?" The woman blushes as if he is referring to her.

As we walk away from the woman with the baby, I ask Toback why women fall for him. "I have an instinct, which is not conscious, for women who are female versions of me," he says.

I ask if Downey has the same instinct. "It may be easier to picture Robert Downey Jr. picking up women," he jokes, especially in his role as Jack Jericho in "The Pick-Up Artist." But the director says Downey was shy and secretive when he was younger.

"I consider Robert my alter ego," Toback says. His decision to cast the 20-year-old, gap-toothed actor, without a screen test or reading, in his first substantial role was an irrational leap of faith Toback hoped "would create confidence in him." The next time audiences saw Downey in a Toback film was 11 years later in "Two Girls and a Guy."

It was Downey's second chance to embody Toback. The director wrote the script in four days with Downey in mind after he saw him on television in 1996, in handcuffs on his way to drug rehab. He thought that the older Downey might have a complexity that would enable him to inhabit another role, that of a liar and philanderer who justifies his behavior because he's an actor who, he says, is always playing a role.

Toback's friends say he chooses to experiment with life as if it were a movie. "Jim has always had the ability to play himself as if he were a part and be totally immersed in it and then stand back and be objective," says film critic (and Salon contributor) David Thomson, who hung out with him in the '70s.

But Toback's lifestyle was more than just lewd drama. "The Jim I knew thought he'd be dead by now," remembers Thomson. "He used to vow to never reach middle age. But the inherent danger in living with little distance between deliberation and action was a break between doing and thinking that attracted a lot of hostility."

What matters more to Toback than critical reception is getting his personal vision on-screen. By embracing and aggressively presenting themes that the MPAA categorizes as too strong, he has thrown away any chance of getting backing from conglomerate production companies. As a result, Toback has tailored his filmmaking to the constraints of independent production.

"Two Girls and a Guy," for example, cost about $1 million to make and was filmed in only 11 days in a Manhattan loft. Mainstream movies can easily cost 50 times that, with fewer time constraints on the production.

But with less money and less time, Toback makes the movies he wants to make. He's working on a scale that is key to any independent movie. "Jim has found a line between art and the commercial mainstream and he's very successful at that stage," says Michael Mailer, a longtime friend who has produced Toback's last three pictures.

Box-office numbers for Toback's films are surprisingly good. Together, his last three movies grossed $20 million. In 1999, "Black and White" brought in $6 million during its entire commercial run and cost $4.5 million to make, a high budget by his standards. (The top box-office performer that year was "The Sixth Sense," which made $293 million on a $55 million budget.)

Years ago, Toback says, top-level Hollywood producer Don Simpson ("Top Gun," "Flashdance") agreed to back "Harvard Man" after Toback read the entire script to him over the phone. Unfortunately, the next morning Simpson woke up, went into his bathroom and died. Toback put the film aside for four years while he made "Two Girls and a Guy" and "Black and White" with the backing of Michael Mailer's company, which later agreed to produce "Harvard Man" as well. To Mailer, the film's appeal was simple: "What it does best is deal with madness, which we're all susceptible to, and Jim captures that creative instability."

Toback seems even more agitated than usual when we meet to go on errands before his afternoon flight to Toronto. A foot of snow covers the ground, and he's pacing back and forth trying to get a taxi. It's 3 p.m. but it seems like rush hour; eight cabs are stopped at the nearest stoplight. When he sees a cab down the street he runs a block, one hand holding a shopping bag, the other in the air. Off duty.

The stoplight changes and a cab stops for Toback. Inside the cab he explains: "I've been outside almost all day by choice, don't know what got into me. Yeah, I went to the park and the paths weren't obvious, so I ended up walking triple the distance and it's making me strange. Inside his bag is a sandwich for his mother and videocassettes of "Requiem for a Dream" and "Jesus' Son." We stop at his mother's apartment on Central Park West; he scurries in to drop off her lunch, and returns to the taxi carrying a bank deposit envelope.

We get out at a newspaper store and Toback asks the man at the counter if, by chance, he has the New York Times from two days ago, or the New York Post and the Daily News from the day before. The man squints his eyes: No. Toback explains as we leave. "I was in the papers yesterday. There was this crazy picture in the Post."

Toback strides across the icy sidewalk and up to a curb, packed with dirty snow. An old, black man, who appears to be homeless, walks past ranting and repeating, "Seven three, seven three," and laughing.

Toback turns around to let the man know he understands: "Where's seven-three?" They share a laugh, and still chuckling Toback turns and sprints across the street. He holds a cab and explains as he slides in: The man was "an old gambling psycho" and the numbers have to do with betting two horses at two tracks.

He seems to get nostalgic. "You know, if you watch a person gamble you can learn a tremendous amount about that person," he says. "Actually, it's the same as if you watch a person sexually. Whether you want to or not you reveal your strengths, weaknesses, essence. Everything that is fundamental about your nature."

Shares