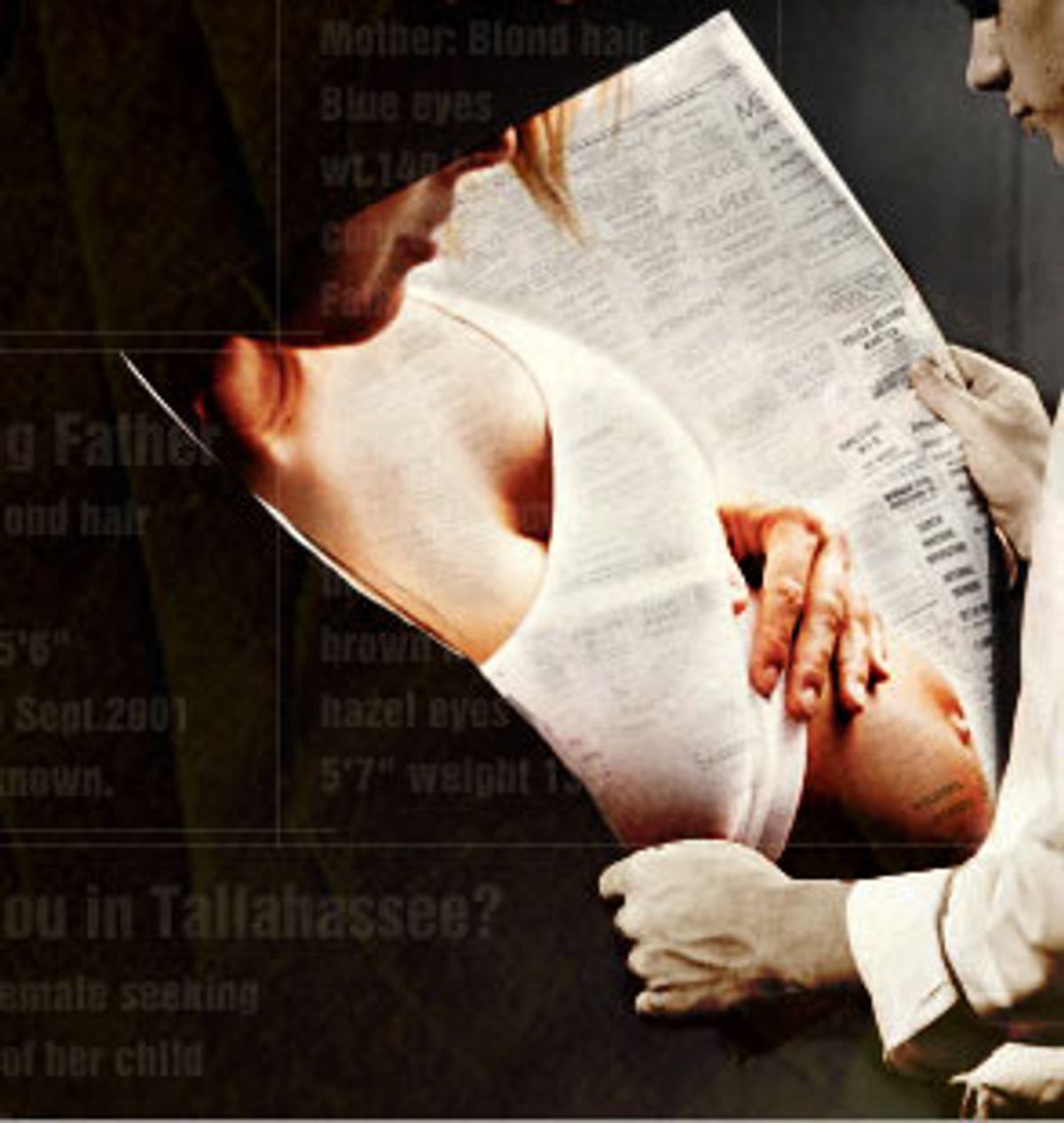

The newspaper ad identifies the mother by name. It says that she has blond hair and blue eyes, weighs 140 pounds and is 5 feet 6 inches tall. Her baby, the ad says, was conceived sometime in September 2001 and the father is unknown, but the mother did have sex that month with an unknown man in Tallahassee, Fla. If that man wants to claim the child, now is the time to step forward.

The ad, which appeared in the Tallahassee Democrat, is one of hundreds of similar notices that have appeared in Florida newspapers since last October, when state legislators passed a new statute governing adoption. The humiliating personal snapshots of one-night stands and regrettable sexual escapades are now required by law when a woman who wants to give up a child for private adoption does not have paternal consent or doesn't know who the father is. The state requires that the ads be published in local papers in an attempt to notify fathers of impending adoptions, giving them a chance to claim their children.

State Sen. Walter "Skip" Campbell, D-Tamarac, who sponsored the bill, claimed at the time of its introduction that the measure solidified the state's constitutional obligation to biological fathers. "In 1972 the Supreme Court of the U.S. revolutionized the area of adoption law by saying that biological fathers have due-process rights so that they can have an opportunity to parent," he said, citing the ruling in Stanley vs. Illinois that gave an unwed man rights to his biological children after their mother's death.

But since its passage, the Florida law has managed to infuriate and alienate a wide and unlikely collection of state and national critics -- including some fathers' groups. Florida adoption professionals are alarmed by both the financial burden and public shame that their clients are forced to bear under the new rule. Antiabortion advocates -- even the Rev. Jerry Falwell -- worry that the law is steering women with unwanted pregnancies toward abortion rather than adoption. And the ACLU and NOW call the measure sexist, unconstitutional and a violation of privacy rights.

Representing six clients, including a 12-year-old rape victim, adoption lawyer Charlotte Danciu has challenged the law in Palm Beach County Circuit Court. Circuit Judge Peter Blanc declared the notification requirement unconstitutional in cases of rape, which was a victory for Danciu's 12-year-old client. But Blanc upheld other provisions of the law, including the notification requirement for underage girls who willingly had sex; Danciu plans to appeal.

Meanwhile, local publicity about the case has triggered a furious debate: How do adoption officials, public or private, make sure that a biological parent has an opportunity to claim a child, without violating the privacy of either parent, or, for that matter, the child?

With between 5,000 to 7,000 annually, Florida has the second-highest number of adoptions in America, just behind California. Adoption professionals attribute these numbers, at least in part, to laws that make it relatively easy to adopt both privately and from the state. This was the case, at least, until last October, when the Florida Legislature overhauled its adoption statute to improve paternal rights.

Federal law requires that before a mother can give a child up for private or public adoption without the father's permission, she must prove that she or her lawyer has performed an exhaustive search to locate the child's father. The requirement is designed to prevent situations in which the father demands custody after learning about the existence of the child much later in the child's life. In the last decade, such situations have resulted in high-profile lawsuits, and men's rights groups have made the issue a priority. For that reason, social workers, adoption professionals, men's groups and legislators in Florida wanted to clarify the process.

For most the 1990s, Florida adoption professionals proposed to solve the problem with a statewide paternity registry that would allow men to register their claims on any child that might be theirs. The registry was supposed to prevent pregnant women from giving away a child without the father's knowledge. Authorities would check the registry before going through with adoption, looking for a potential biological father with an interest in the baby. More than a decade ago, as Florida considered creating a registry, the concept was new and only a few states had them. Today, nearly half the states in the country have registries.

Attorney Danciu decided to help write a bill proposing a Florida paternity registry after defending the adoptive parents of controversial "Baby Emily," a Florida child whose biological father, a convicted rapist, had claimed -- long after the adoption -- that he wanted the child, despite the fact that he had failed to show up at early court hearings about the adoption. The court eventually granted custody of the child to her adoptive parents.

The measure didn't receive much support from Florida's conservative state government, despite lobbying from the state's adoption community. Some male senators laughed and called it a "sex registry," recalls Danciu. Others were concerned about confidentiality in a state where all public records are open to the public unless they are awarded a special exemption. What if a man had an extramarital affair, registered it, and his wife somehow saw it? wondered the lawmakers. "Lists can be dangerous," state Sen. John McKay told the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel at the time.

Recalls state Sen. Debby Sanderson, "When we were talking about a paternity registry, one senator said 'That could wreck a married man's life.'"

The bill died, but legislators, still concerned about paternal rights and cases like that of Baby Emily, came up with what they thought was a better idea. Instead of forcing men to disclose messy details of their lives in order to have a say in a baby's future, the mothers would have to publicly advertise their sexual histories in newspapers to give the men a chance to identify themselves -- or not. This alternative plan, which became part of the new adoption statute, became law in October 2001: The 106-page statute was pushed through the system in just two days. Only eight senators voted against it.

The notice provision requires that women who cannot identify the fathers of children up for private adoption take out ads that list their names, addresses and physical description, along with the names of all of the men they had sex with during the 12 months before the baby was born. The ads have to run once a week for four weeks in all the cities where the baby could have been conceived. If a woman had sex with 20 men in 20 cities, she is required to buy newspaper ads in all of them.

Although there is no official count, adoption professionals guess that the law has affected hundreds of mothers since it was signed into law. Jeanne Tate, an adoption lawyer and executive vice president of the Florida Association of Adoption Professionals, says that during one recent week she helped 10 of her clients place ads; since October, her office has placed 50. Her guess is that hundreds of ads have been run in the last 10 months.

The cost for the ads can be prohibitive: One ad might cost a few hundred dollars, but a sexually active woman who has moved around a lot could end up paying thousands of dollars. (The legislators made exemptions for state adoptions so that the state wouldn't have to pay the cost of the ads; only those who choose private adoption are forced to take out ads).

But the humiliation and potential danger inherent in publicly announcing sexual encounters with vanished or forgotten partners is far more debilitating than the cost of the ads. Melissa, a pregnant 18-year-old student, is now required to publish a notice in a Bronx newspaper about her one-night stand with a man she barely remembers.

"I'm disgusted," she says. "I don't feel that I should have to put my sexual history in a public newspaper. It's embarrassing enough that I made a mistake and have to do this. I'm going to college and don't want anyone to know. I'm [giving up the baby] to change my life. But this makes me feel ashamed."

Nancy, a 41-year-old Palm Beach County mother, says she was impregnated by a violent boyfriend who subsequently locked her out of her home and disappeared when it came time to sign any paperwork for the adoption. Fortunately, she gave birth before the new law went into effect: Without paternal permission, she would have had to put ads in the papers.

"Given his past behavior, if I had published his name in the paper for everyone else to see, it could have triggered something unpleasant. I would have had to hide from him," she says. She also had concealed the pregnancy from her family: "A newspaper record of this would have estranged me from my family. It's a huge invasion of privacy."

The consensus among adoption professionals is that the law has already had a chilling effect. Many birth mothers already have agreed to take out the ads, but others are deciding that it's too much, and are choosing to forgo adoption altogether. Danciu estimates that she's lost 15 clients who came in to arrange adoptions but left when they realized the burdens involved. Instead, she says, fearful mothers are either choosing to keep the child or have an abortion.

It's this alienation from private adoption that has led local antiabortion organizations to line up against the law -- despite the fact that the Florida Catholic Conference was initially one of its biggest proponents. Charlene Hubbard, adoption coordinator at the pro-life Brandon Care Pregnancy Center, says that the number of women who come to the center and agree to put their children up for adoption has dropped more than 25 percent this year. "Once they realize what the laws are and the hoops they have to jump through, then it's too much trouble," she says. "It's a whole lot easier to go to the corner and have an abortion."

Even the Rev. Falwell agrees: "This is a bad law," Falwell said recently on "Hardball." "This will encourage abortion rather than adoption."

Forcing women with unwanted pregnancies to keep their babies very often is a devastating -- or dangerous -- alternative, say some critics of the law. Hubbard recently watched with concern as two mothers in her center made that choice, even though they clearly weren't ready to be parents. "The birth fathers caused an issue and the girls did not want to go through all that hassle," Hubbard says. "They chose to parent because they knew it would be a battle. That's not always the best decision."

The fear that motivated the law -- that pregnant women would hide babies from their biological fathers -- is unfounded, say adoption officials. It rarely, if ever, happens. "It always concerned us if we'd do an adoption and the father came back later," says Danciu. "In 18 years only two fathers have ever come forward because they didn't know the woman was pregnant, but both of them ultimately agreed to the adoption. And I've done over 2,000 adoptions.

"A lot of times the pregnancy is a mistake, a lot of times it's an assault, and sometimes they financially just can't do it," she continues. "But it's not because they are trying to hide a baby from the father: If he was there and offering financial support, they'd be having it."

As an example, Danciu points to the six clients she represents in her lawsuit challenging the statute. Aside from the 12-year-old rape victim, there is a troubled 14-year-old girl who had sex with a number of her classmates. Another woman, a mother in good standing in her community, was slipped the date-rape drug Rohypnol and assaulted by three men; two other women were substance abusers. These weren't exactly women who had been impregnated by responsible fathers; and yet they would still have to recount the mortifying facts of their sexual encounters in public papers -- for their classmates, communities, families and strangers to peruse.

Another purpose of the Florida law is to protect fathers' rights to their biological children, an issue that has dominated the agenda of many men's rights groups. Earlier this month, these groups were up in arms about the case of a Pennsylvania woman who wanted to terminate a pregnancy against her ex-boyfriend's wishes. The boyfriend initially received a preliminary injunction preventing the abortion, but it was later overturned by a higher court.

"[A man] has a large personal stake in a decision in which he is not allowed to take any part," objected Dianna Thompson, executive director of the American Coalition for Fathers and Children, in Newsday. "His wishes are irrelevant. When it comes to reproduction, in America today women have rights and men merely have responsibilities."

But if the Florida adoption statute was intended to protect men's rights, it's had an unintended effect: The men get the short end of the stick, too. After all, the notices can list, by name, the men involved in the sexual encounters described, even if there is no real evidence that they impregnated the woman who took out the ad. As Melissa observes: "What if they are not the father, and they have that information in the paper? It's not discreet by any means."

And even if a man was interested in locating an elusive mate in order to retrieve his baby, an ad in a city paper many months or years later seems a rather clumsy route to finding her. People move all the time, after all; or simply don't read the papers.

Still, some fathers' groups shrug at the Florida law, saying that if a birth mother has to suffer public humiliation in order to find a biological father, well, that's just too bad. "Why not? Are we saying we're not responsible for our actions and our shame should cover up anything we did wrong, to the detriment of the child and father? Are we saying she has no responsibility for her own actions?" asks Lawrence Hellmann, president of the National Congress for Fathers and Children.

Biological fathers do, of course, have the right to be notified; everyone seems to agree that efforts should be made to find them. But, as Jeanne Tate puts it, "There are many, many ways to give notice to the birth father which don't include such an invasion of the mother's privacy rights."

An alternative way to locate a birth father is the paternity registry. Now that so many states have them, even President Bush has advocated them; and U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., is currently drafting a bill that would, if passed by Congress this September, create a national paternity registry.

"We've been working on this for quite a few months," says Lindsay Ellenbogen, a spokesperson for Sen. Landrieu. "It's not in response to what's going on in Florida, but it's a good example of why this is needed ... It's all confidential, whereas in Florida that's hardly the case."

But the paternity registry is flawed, too: Is it realistic to expect that a man who wants a child will go sign a registry every time he has sex? Not surprisingly, some men's rights groups don't support this system either. "Paternity registries are kind of 'Brave New World, 1984': They are inhumane," says Fred Hayward, executive director of Men's Rights Inc. "So, it's his obligation to go down and register himself as a potential father and if he fails to do that he only has responsibilities, no rights? That's ridiculous. It's demanding a standard of behavior of potential male parents just a hundred times higher than what we demand of female parents."

So what is the best way to locate unaware or elusive biological fathers? Hellmann proposes an extreme option: Punish the mother if she doesn't seem forthcoming. "It is a woman's obligation when she gets pregnant to do everything she can to identify the father. If a mother shows she's not interested in doing that, take the child away from her until she is." Clearly, this is not an alternative likely to receive support from women, their advocates or constitutional lawyers.

Meanwhile, Florida legislators, chastened by negative publicity from the lawsuit, are already talking about revising the notice requirement -- perhaps eliminating some of the personal details that women are asked to disclose, or striking the law altogether. Even Sen. Campbell is now agreeing that the legislation is flawed. "We gotta fix it," he agrees.

"I imagine that now that this has hit the light of day there will be some changes made by the Legislature; it should be the case. Otherwise we might as well just bring back the stocks and public flogging," says Kim Gandy, president of the National Organization for Women. "It seems almost pointless to say what an outrage it is."

But even if the Florida furor results in the elimination of the law, it does not solve the conflict inherent in the search for biological fathers and the preservation of the right to privacy -- for both parents and the child. As Fred Hawyard puts it, "The ads are a terrible solution. But not doing anything is an even worse solution."

Charlotte Danciu, for one, hopes that the debacle in Florida will raise an issue that appears to have been forgotten in the heat of battle -- the well-being of unwanted children. "It's time that we stopped being so concerned about the biological parents' rights, and instead thought about the rights of the kids they bring into the world."

Shares