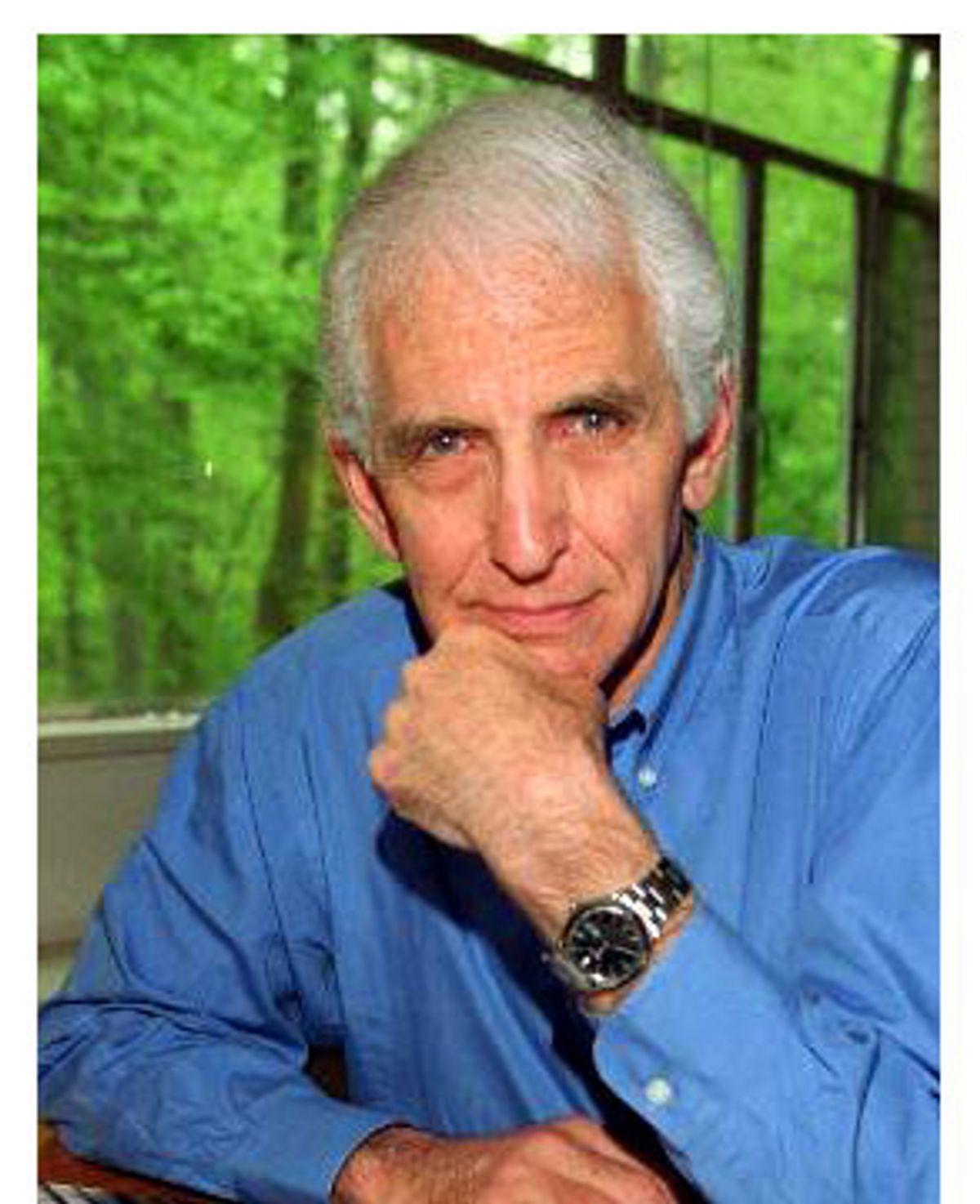

In times of war, Americans tend to give the president the benefit of the doubt. They assume he's acting rationally, on the basis of access to classified information they can't know about. But in his new book "Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers," former Defense Department analyst Daniel Ellsberg demonstrates that such assumptions can be false.

"Secrets" describes, as no book has before, exactly how American leaders deceived the public about a war plan that they knew could not win in Vietnam -- even as they sent increasing numbers of soldiers to fight and die there. As the U.S. prepares for a war against Iraq whose outcome no one can foresee, many will ask if we're doomed to repeat this history of deception. Few people are more qualified to explore this question than Ellsberg, who risked prison in 1971 by leaking the Pentagon Papers, 7,000 pages of top-secret memoranda by Vietnam policymakers, to the New York Times.

Ellsberg understands U.S. Vietnam policy perhaps better than any living American. In his New Yorker review of "Secrets," Nicholas Lemann joked that Ellsberg was the Forrest Gump of the war, turning up everywhere, from remote hamlets in Vietnam to the inner sanctums of the Defense Department. Ellsberg was at the Pentagon reading cables from the destroyer Maddox when it reported being attacked by the North Vietnamese in the Gulf of Tonkin on Aug. 4, 1964, the incident that convinced Congress to give President Lyndon Johnson a blank check to wage war in Vietnam. He was on an airplane with U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara when the latter exclaimed privately that U.S. forces were losing in Vietnam -- and then publicly declared that "I'm glad to be able to tell you that we're showing great progress in every dimension of our effort" at a press conference when they landed. And he risked his life on the ground in Vietnam in a quest to understand the real war, driving roads with U.S. advisor John Paul Vann that no other Americans would dare travel, observing U.S. helicopter pilots hunting Vietnamese peasants like animals, and engaging in combat himself against Viet Cong forces.

But Ellsberg is also one of America's foremost experts on Vietnam policy because of his insatiable curiosity about the war, and the culture that spawned it. He has spent much of the past 40 years trying to understand how U.S. policymakers could have waged America's first losing war at a cost of the death of 58,000 Americans and 2-3 million Indochinese. He goes beyond his book in this Salon interview to speculate on the motives of American leaders, and to draw the parallels he sees with today's U.S. policy toward Iraq.

The issue is not whether Iraq is "another Vietnam," a slogan opponents have used to discredit American military adventures from Central America to Afghanistan. The Iraqi army enjoys nothing like the popular support the Vietnamese communists enjoyed, and the war is unlikely to last for a decade. But any number of reasons why the U.S. failed in Vietnam could have relevance in Iraq -- most notably, cultural and historical ignorance on the part of U.S. policymakers. As McNamara observed in his 1995 Vietnam memoir, "In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam," "Our misjudgments of friend and foe alike reflected our profound ignorance of the history, culture and politics of the people in the area, and the personalities and habits of their leaders." Ellsberg believes that our present leaders are equally ignorant of Middle Eastern politics, and worries that a unilateral American strike against Iraq could turn the Muslim world even more against the U.S., costing the support of Muslim countries in the war on terror and helping create a new generation of terrorists.

Whether or not one agrees with Ellsberg's analysis, reading "Secrets" makes clear that Vietnam is not merely history. Presidents are still capable of acting irrationally and distorting the truth, and Congress is still too willing to cede war-making power to the executive branch. Even more disturbing, it reminds us that American leaders have made wartime decisions that weakened rather than strengthened national security -- but that asking questions about our war aims is patriotic, not subversive.

What are the major lessons from Vietnam that today's young people, who may not know very much about the war, should know?

Very smart men and women can adopt and pursue wrongful and crazy policies, and get those policies adopted and followed. And they can keep the basic illegitimacy and craziness obscured, at least, by secrecy and lies about its causes and prospects. The Pentagon Papers show that all U.S. presidents over a 23-year period lied, virtually continuously, about what they were doing, what they intended to do, what the costs were expected to be, what they actually had done, and about what the reasons for doing it were.

The 7,000 pages of the Pentagon Papers prove that nothing our leaders said should have been taken at face value. It's naive and even irresponsible for a grownup today to get her or his information about foreign policy and war and peace exclusively from the administration in power. It's essential to have other sources of information, to check those against one's own common sense, and to form your own judgment as to whether we ought to go to or persist in war.

Why do you use the word "crazy" to describe our policies in Indochina?

The most widely accepted explanation given for increasing our involvement in a hopelessly stalemated war, which got larger and larger from year to year, with no perceptible progress, was that the president had been drawn into a quagmire by overoptimistic advisors, particularly the military. The idea is that the president, thinking of other matters and not focusing on Indochina very much, simply followed military advice in what he did.

But the documents prove that no aspect of this was true. No president had ever been told that involvement in Vietnam would lead to success, quickly or easily or on a small scale.

The Joint Chiefs did recommend that we get in, but only on a very large scale. They wanted him to greatly expand the war beyond the borders of South Vietnam into Laos and Cambodia and North Vietnam itself, on the ground. They also wanted a much greater expansion of the air war, right up to the borders of China and if necessary beyond those borders. Had we followed that policy Chinese ground troops would almost surely have come in, which would have led to pressure by the Joint Chiefs and others for the use of nuclear weapons. The Joint Chiefs I have to say in that instance look almost incomprehensibly crazy in their willingness to risk nuclear war. That looks crazy.

And the actual policy that successive presidents actually did follow -- which was of large-scale ground and air involvement in South Vietnam, with large but limited bombing in North Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia -- was almost as irrational.

The United States was never prepared to allow self-determination in South Vietnam, because a democratic election would have led to communist participation in power and probably a communist-led government, since the communists had the prestige and the organization that grew out of having successfully defeated a colonial power.

Just to postpone that result, president after president was willing to send many people to die and to kill. Now, understood in those terms, one then stands back from the policy and says, but humanly how is this to be understood? It looks crazy. That's what I mean by crazy, a crazy disproportion between the human costs and the risks of the effort, and the legitimate benefits if any that can reasonably be expected.

What I'm saying is that very smart men -- and nobody is smarter than McNamara, and the Joint Chiefs were not dumb people by any means -- were espousing a terribly unwise policy that could lead to a catastrophic result.

What are some of the major lies that were told in support of this policy?

My first night in the Pentagon, on August 4, 1964, I heard my president, Lyndon Johnson, saying that he was retaliating against North Vietnam because of unequivocal evidence of an unprovoked attack on U.S. destroyers in the Tonkin Gulf that were on routine patrol in international waters. And that this retaliation was limited and that "we seek no wider war." Now that's five or six separate assertions, and I already knew within hours or days that every one was false.

Did they tell Congress things that they didn't want to tell the public, on the grounds that it might help the other side?

Yes, they did tell Congress things that were not made public at the time, or for years thereafter. And nearly all of the things they told Congress in joint committee hearings, in top-secret closed sessions, were top-secret lies. In other words, Congress was lied to just as egregiously, and to the same effect, as the public.

You also say in your book that they lied about the progress we were making in Vietnam once we began to send U.S. troops, a process that began in February 1965 that saw a high of 500,000 men at any one time, 58,000 dead, and more than 3 million troops sent between 1965 and 1973.

Yes, and that's the decision that looks so crazy given what the president knew the prospects were. The president knew from the fall of 1965 that he was getting into a very large war, which would probably go to a scale of 500 to 700,000 troops or more. But the public was never told that.

Instead he constantly implied that the last 20,000, 40,000, 50,000 troops that were sent were all that was required "at this time." The scale of the war to be expected was never explained to the public, lest it cease to support the war, lest it call on Congress to force negotiations, force coming to terms in some way and ending the war. So that was always lied about.

The prospective costs of the war were also concealed from the public. For example, Clark Clifford (U.S. secretary of defense in 1967-68), in arguing to the president on July 23, 1965, at Camp David, said to the president, "I see nothing but catastrophe for my country." He then gave an amazingly prescient prediction that the war would involve 500,000 U.S. troops and 50,000 U.S. dead. "That is not for us, Mr. President," he said. But it was. We sent 550,000 troops and lost 58,000 killed in action.

We know from Johnson's tapes that he rarely did believe that we were headed for any kind of success from beginning to end. He was saying to his mentor and close friend, Sen. Richard Russell, the head of the Armed Service committee, things like, "I don't think they'll ever quit, and if I was in their position I wouldn't. They're going to keep going and we are not going to beat them." This is while he was sending boys to die.

Why do you believe Johnson behaved so unwisely?

Well, I don't speculate on motives in my book, but since you ask I'll give you my own personal opinion. For a long time I believed his motive was essentially domestic politics, that he believed he would lose office if he was accused of losing Vietnam to communism. I would say that is the consensus explanation right now. And also that he believed it would hurt us internationally, if our credibility was destroyed and so forth.

But I have decided that this explanation does not square with what was then knowable about domestic politics. The president's decision to escalate went against that of his political advisors such as Hubert Humphrey, Clark Clifford and Richard Russell. I would say that he had no domestic risk at all in getting out of Vietnam in '65 after the defeat of Goldwater. Had he done so, even with a Communist South Vietnam, he would not have had inflation, he would have had money to spend on his war against poverty and his Great Society programs, he would not have provoked the domestic political crisis that forced him to not seek reelection in March 1968, and so forth. And I do not believe that was unforeseeable in 1965.

I would say that he consciously chose a policy that was riskier for him politically than the alternative. So how do we explain that? My best guess is that Lyndon Johnson psychologically did not want to be called weak on communism. As he put it to Doris Kearns, he said he would be called if he got out of Vietnam, an "unmanly man," a weakling, an appeaser.

He preferred to risk office, and to lose office, as a tough guy, than to gain and retain office while facing some strident charges from politicians who were beaten that he was a weakling. And I believe that he was not alone in that. Many Americans have died in the last 50 years, and maybe 10 times as many Asians, because American politicians feared to be called unmanly.

You're saying this is a psychological fear.

I think there is a heavy psychological element in it, and that from 1965 to 1968, there was not a realistic political aspect to it.

Was this only true for Johnson?

Five U.S. presidents behaved unwisely in Vietnam, though Johnson and Nixon of course did the most damage. And the question has remained for 30 years since the war ended: Knowing what they knew how could they have done this? Since the policies made so little sense politically or economically, I have concluded that staying in office and avoiding certain charges of weakness, of unmanliness, of softness, and weakness on communism, or weakness in any way at all, was their main motivation.

Each of those is seen as a kind of overwhelming importance to the individual people. People outside the president and his subordinates say, "Well, we can understand motives like that, but are those reasons for killing hundreds of thousands of people, for sending Americans to die, risking nuclear war? It's hard to imagine humans doing that."

But the truth is that those humans in office -- who, before reaching that point, were individuals like anyone else -- find themselves drawn to make choices that appear insane to most outsiders, and the outsiders are right.

Is the solution to elect honest leaders to office?

There seems to be no prospect of that. History gives us no reason to expect that statesmen of any party or nation will be willing to tell the truth about what they are doing.

I think the answer is what the founders amazingly wisely provided for in our Constitution, which is to prevent any one man from making the decision on war and peace on his own. They left the decision exclusively in the Constitution in the hands of a broad representative body, the Congress. And secondly, you can't let the decision of how much to tell the public about matters of war and peace be exclusively in the hands of that one man. Because that gives him the war power that makes him a king. A king in foreign policy is close to what we've had in the past 50 years. And it's what we have now. And we should get away from it. We should go back to the idea of checks and balances, and the war power residing in Congress, not the executive branch.

Do you believe our current policies toward Iraq are as irrational as our policies in Indochina a generation ago?

Yes, I do. I believe that an invasion of Iraq will increase the danger of terrorism to this country, and thus will be measured in American lives. Al-Qaida is a real threat to this country, and I believe the chance of al-Qaida getting weapons of mass destruction from Saddam will be greatly increased if we attack Iraq, by the spectacle of Muslims, civilians and military, being killed by the United States.

I think that will increase the availability of weapons of mass destruction to al-Qaida, and Americans will die as a result of that, in addition to whatever else al-Qaida can do.

Secondly, al-Qaida will acquire tens or hundreds of thousands of new recruits for suicide attacks, in the wave of rage I think will sweep over the Muslim world when they see this war being conducted for what they correctly perceive as being without justification, as a war for oil and other purposes that don't justify it.

Third, the possibility of cooperation with the U.S. by governments of countries with large Muslim populations, which is essential to the struggle against al-Qaida, will become impossible for those governments. They will find themselves unwilling to do what will cost them their office and perhaps their lives.

They will not be able to cooperate with the U.S., after we've killed many Iraqis in this war. And without that cooperation again, al-Qaida's task becomes easier, and Americans and other Europeans and others will die as a result, including Israelis, just as I believe Sharon's policies are at the cost of many more Israeli lives than they are saving.

So far we've talked about the war mainly as irrational. But you have famously described the war not as a mistake but a crime. You base this charge on the evidence in the Pentagon Papers that U.S. leaders from 1954 to 1968 knew they were opposing self-determination in South Vietnam, and were waging an aggressive war against a people who did not threaten us. What impact did your conclusion that the U.S. was morally wrong in Vietnam have on your actions?

The evidence made clear that our war was a crime against the peace. And for me to see that impelled me to take nonviolent actions I was not led to do when I considered it simply a mistake. When I saw the war as unjustified homicide, it seemed to me that it should stop not just gracefully or whenever possible, but that it should stop as soon as possible. I decided I should do more than I had yet done, a course that involved great risk for me including life in prison.

Do you also believe any war against Iraq would also be criminal?

Even if there was a threat, it is not a threat that would justify the extreme dangers of committing mass murder against civilians that is likely to occur, and even the murders I think of Iraqi soldiers. Unjustified aggressive killing of Iraqi soldiers is also murder. Iraqi soldiers have not done anything in the past five years or so, certainly not in the past year, that sentences them to death by our president or by our Congress or by the U.N.

So whoever authorizes it, it's aggression and it's murder. And by the way we were earlier asking, well, what difference does it make to call it that, death is death, what does it matter whether you call it murder? It made a difference to me when I was a Marine, when I was in Vietnam, and finally when I came to see what we were doing as murder, I didn't want to participate in murder or aggression. And I went further than to avoid that than I would have done.

And I think right now if people came to perceive what we were doing as totally illegal and unjustified, they might do more to oppose it than they would otherwise. I don't have a lot of faith that that will come about. The media will simply not allow that perception on the whole to emerge. But I do think a media doing its job and senators to some degree doing their job, as 23 did do, can get across the fact to the public that the human costs and the risks of this are enormous.

What do you think a person in the Bush administration who opposes this war should do?

I encourage people who are in the position now that I was in then -- namely of seeing us about to embark on a wrongful, unjustified and illegitimate war that is a crime against the peace -- to consider doing what I wish I had done in 1964.

That is, if they have documents indicating that the president is lying the public into such a war, they should take those documents to the Congress and to the press, and tell the truth -- even if it costs them their clearance, their job, their career, even if puts them in prison.

You have remained an activist for the 30 years since you revealed the Pentagon Papers. Do you ever feel like just giving up?

Where there's life, there's hope. For instance, if the bombing stops, there's a small chance of avoiding an invasion. If an invasion starts, there's still a chance of avoiding nuclear weapons. And if nuclear weapons happen, what then? Well, I will feel like dying, but I will also pick myself up and say, well, let's make what we can to avoid it happening next. There really is always the next time. We're not facing the world blowing up as we did during the Cold War. It will take a miracle to stop this war, but not more of a miracle than South Africa having a peaceful transition, not more of a miracle than the Berlin Wall coming down and East Europe being liberated.

Shares