Something rankles me about filmmaker Susan Raymond's deadpan description of "Lance Loud! A Death in an American Family" as "a celebration and a cautionary tale," mainly because it never really becomes clear in the film who exactly is being warned, or what exactly they are being warned about.

If "Lance Loud!" is intended to caution the kids now joining the cast of "The Real World" or trying out for "The Bachelor" about the perils of prefabricated, unmerited fame, then it really needn't bother. Unless any of those kids are campy vamps given to Oscar Wildean quips (which seems unlikely), or harbor dreams of making a splash in the underground art world (which seems unlikelier) or are possessed of a gimlet-eyed self-awareness and a sense of humor about themselves and their ravenous need for attention (I'm sorry, what?), they are in little danger of turning into Lance Loud.

"Lance Loud! A Death in an American Family," airs Monday night at 9 p.m. on PBS, and chronicles (at his behest) the last days of the first reality TV star. Loud died in a Los Angeles hospice in 2001, at the age of 50, of liver failure brought on by hepatitis C and HIV infection. "I want you there when they wheel me out," the most notorious member of the Loud family tells the filmmakers at the start of the film. "I can't leave the planet without some closure from the series."

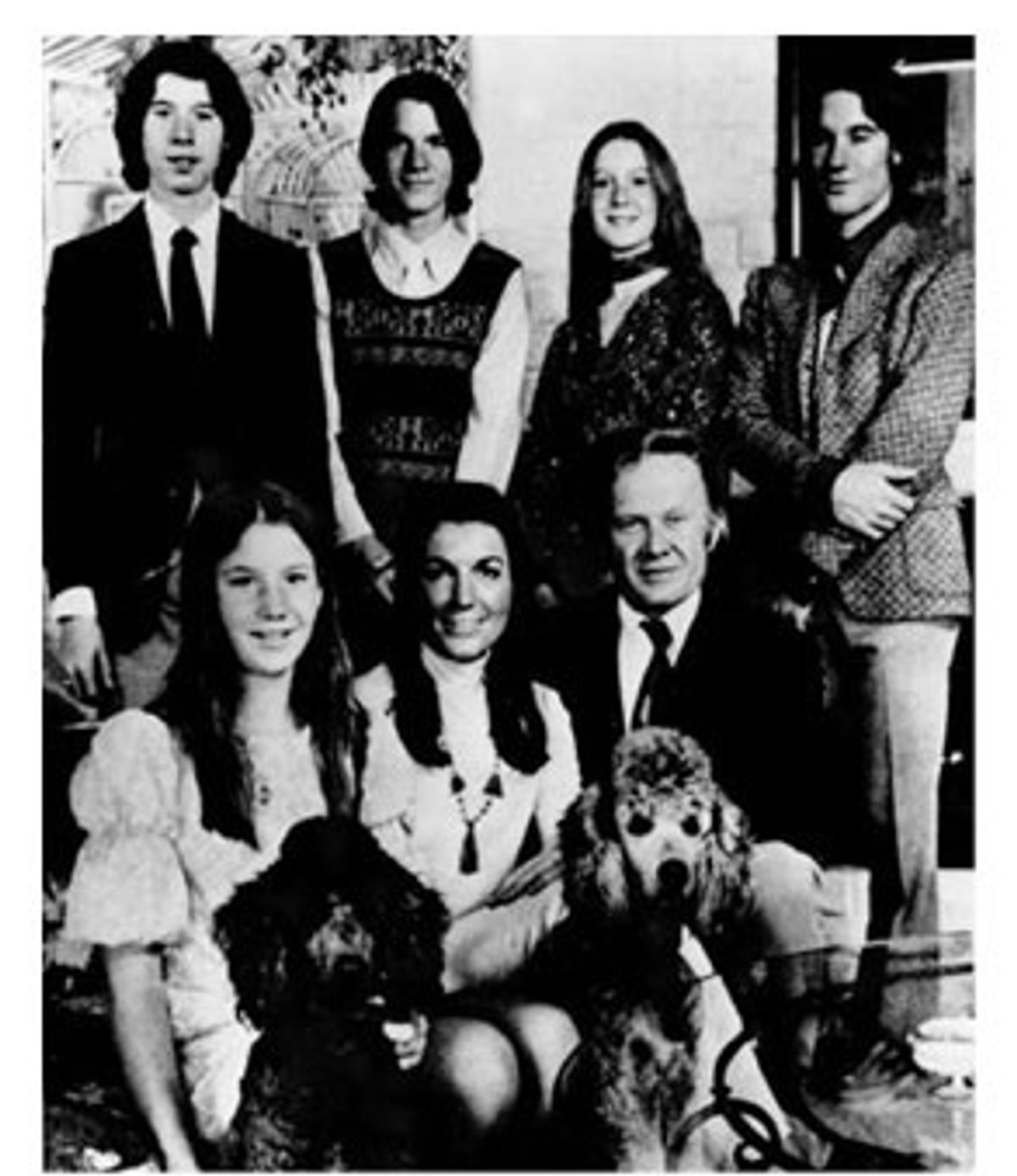

The series in question, for those of you too young or attention-span-impaired to remember, was "An American Family," which hit the air in 1973 like a saucy slap. It was a 12-hour distillation of the months Raymond and her husband, Alan, spent living in the home of one affluent Southern California family. The eldest son, 20-year-old Lance (who was also the first openly gay character on television), became famous for his willingness to flaunt his sexuality and his nonconformity at every opportunity. His exhibitionism worried even the Raymonds, who would occasionally take him aside during the filming and admonish him to think about how he would be perceived by the public.

It's hard to imagine anthropologist Margaret Mead, who declared "An American Family" to be as "new and significant as the invention of drama or the novel -- a new way in which people can learn to look at life" ("Margaret was great," Lance quipped at the time. "I had to sleep with her to get that quote"), warning teenage Samoans in a similar fashion. ("Now, dear, you don't want the whole Western world thinking you're a slut, now do you?")

"An American Family" was savaged by critics, who one might think would have been happy for the reprieve from "Leave it to Beaver," "Father Knows Best"-style depictions of American middle-class family life. But no. Establishing a cherished tradition that flourishes to this day, they reserved their harshest judgments for the show's subjects. Lance received the lion's share of the opprobrium for opening up his personal life for millions of eager viewers. During the making of the film (or possibly as a result of it), Pat and Bill Loud's marriage disintegrated and Lance, buoyed by the encouragement of Andy Warhol himself, fled the suburbs for New York to pursue a hazy dream of stardom.

Thirty years later, "Lance Loud! A Death in An American Family" feels like it's trying to gauge how much damage the series inflicted on the Loud family, and whether it played a part in shaping Lance's difficult adult years. Ultimately, his freebie fame obscured Lance's own, self-driven efforts; but you get the sense he would have made those efforts anyway -- possibly with even less felicitous results -- had the Raymonds never come along. After the series ended, he fronted a cult punk band called the Mumps for seven years, but never got a record contract. He buffered his disappointment with a "Behind the Music"-style 20-year drug addiction while working as a journalist.

Lance was handed an audience of 10 million people, but the role he played in the series and in his life was his own fluent and ephemeral creation. He was, as he put it then, "dedicatedly stupid" and cheerfully unapologetic about it. For a young kid described as an "affluent zombie" by one critic and as a "Goya-esque emotional dwarf" and an "evil flower" by another, he handled attacks with remarkable urbanity and aplomb. As he quipped to Dick Cavett after reading that particular assessment of his character, "That was the one that really hurt. But I took two aspirin and it went away."

"Lance Loud!" can't seem to work out whether "An American Family" did Lance a favor or did him in. (Neither, for that matter, could Lance.) But watching old footage of him as a young man, intercut with scenes from the end of his life, you get the feeling he was going in that direction anyhow. As he says, the Louds were "headed for destruction" all on their own. The Raymonds just gave them a lift.

Even before the filmmakers came along, Lance was nurturing the kinds of dreams and inchoate artistic aspirations that come with side effects. They seem to have been offset somewhat by his exuberance and humor ("I'm still big," a gaunt, weak, toothless Lance jokes at the beginning of the film. "It's documentaries that got small!") and a relationship with his family that bordered on the Walton-esque. (Lance's dying wish was to see his parents reunited, and they honored his request.)

Watching Pat Loud cuddle her dying 50-year-old son, you might wonder if maybe the Louds aren't a lot like the Cleavers after all, and whether the Raymonds are public television's answer to Jerry Springer. In any case, Susan Raymond's warning cuts both ways. Or, it doesn't cut at all, and merely crackles with an infanticidal urge. Thirty years after "An American Family," the Raymonds are being credited with inventing reality TV. Maybe it rankles them. If your baby grew up to be "The Real World: Las Vegas" you'd probably want to kill it, too.

Shares