Youth, and a healthy dose of naiveté, make love and lifelong companionship seem gloriously possible. Young couples make promises. They dream of a home and maybe a family. And they look forward to their wedding day, the moment when they can officially set their future in motion.

For the young people who graduated from college and high school in the booming 1990s, the future seemed endless. A new economy was taking shape, jobs were plentiful, and terrorism was something that happened far, far away.

Now all that has changed.

As the unemployment rate hovers around 6 percent, the same people who were so employable just a few years ago are now scrambling to make ends meet.

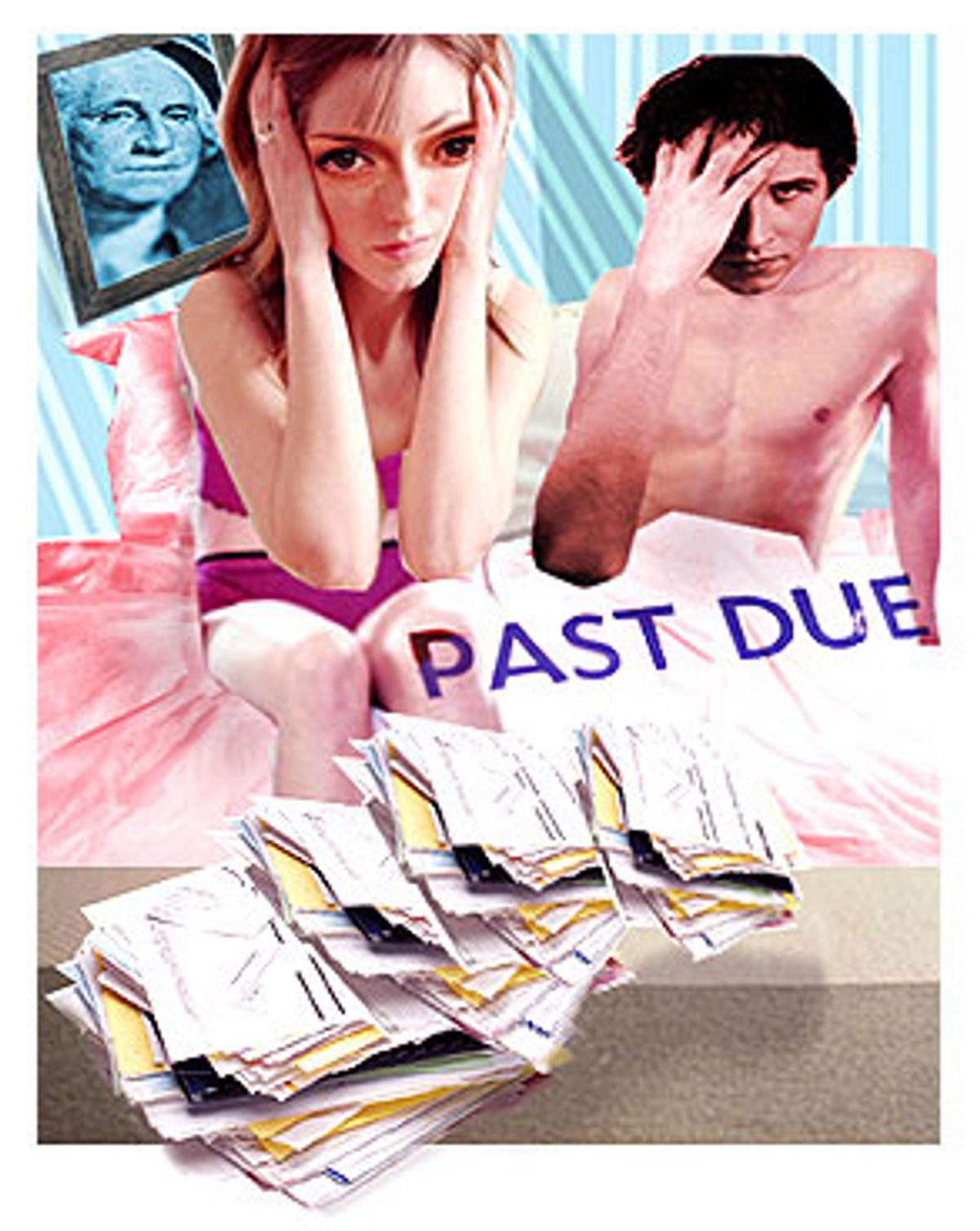

If Sept. 11 jolted young people to the altar, as various articles suggested, then this recession, the worst since World War II, might be pulling lovers apart, or at the very least, delaying their nuptials. Instead of planning their weddings, many young couples are sitting around the kitchen table and, for the first time, fretting over how to pay the bills.

While economic instability of course manifests itself in depleted bank accounts and 401Ks, it also wreaks havoc on home life. Losing a job, not being able to contribute to a relationship, just not having anything to do all day, makes people irritable, insecure and resentful. In fact, according to some experts, financial problems are the major cause of 80 percent of the divorces in the United States.

"When people are out of work, it is extremely tough on their self-esteem," says Nancy Collamer, a Connecticut career counselor who was inspired to write "The Layoff Survival Guide" after her husband lost his job in 2001. "Their partner is expected to be the cheerleader. But the partner is in a tough spot, because they're going through those same feelings of anxiety. Once I had someone say to me, 'I've gotten to the point where I can't stand the way he chews pretzels.'"

That's the small stuff. Some young couples are wondering whether they'll have to drop out of school or apply for food stamps. They're slamming doors when the word "wedding" is uttered. Sex? They're not having sex for weeks.

The current recession, of which young couples are just one of the many hidden victims, may fundamentally alter what we think of as "middle class." Many assumed that they'd follow in their parents' footsteps, that they'd be financially secure because of their upbringing. But they can't even go to their parents -- who often have their own financial woes to cope with -- for help.

Therapists and counselors find that financial problems affect relationships similarly -- regardless of class. Upper-class couples are fighting over pedicures and DirecTV, luxuries that seem impossibly frivolous when others can't scrape together enough for a haircut or a video at Blockbuster. But whether it's in buying a new car or finding enough to eat, financial strain can be cataclysmic.

"Even though a middle- to upper-class couple, in theory, has more resources, their lifestyle is right up where their income is," explains Patricia Pasick, a marriage and family therapist at the Ann Arbor Center for the Family, in Michigan. "And so they're just as in danger of defaulting on a loan as a working-class couple is in danger of not being able to pay rent on their apartment. Regardless of class, the general anxiety seems to be the same."

Even so, the stories young couples tell aren't necessarily gloomy. Some of them feel the hardship is making their relationships stronger. They've seen tough times, which ain't pretty, but they're confident that if they're still sharing a bed after all these financial problems, then they can make it through anything. Certainly, it can't get any worse. Right?

- - - - - - - - - - - -

A few years ago, budding filmmaker Anna Boudinot was dreaming of Sundance. A graduate of New York University's prestigious Tisch School for the Arts, she financed a short film on her credit cards, hoping to eventually get private funds to develop a feature-length movie.

But first, romance. After graduation, she moved to Berwyn, Ill., just outside Chicago, to be with her high school sweetheart, Glenn McDorman, 25, an Army veteran who now attends college there. They got engaged and Anna found a decent-paying receptionist's job to cover the bills.

Then, a week before Christmas 2002, Anna, also 25, lost her job. The waitressing gig she picked up soon after paid only about $100 a week -- not nearly enough to support herself. She didn't have enough money to buy groceries, and Glenn was paying her share of the rent and all of the other bills with the money he earned at his part-time retail job. Anna felt guilty that she couldn't pitch in and that led to a deteriorating self-confidence and shame that wore on the relationship, no matter how reassuring Glenn could be.

Feeling guilty that she was draining Glenn's bank account, Anna searched the Internet for information about public assistance. To her surprise, she qualified for food stamps. But before she went to the Department of Human Services to fill out the forms, she took off her engagement ring, fearing that the diamond might prejudice the caseworker against her.

"It was humbling to go get food stamps," she says. "Sitting there with people who were clearly homeless and knowing that we had something in common."

Anna didn't even consider turning to her parents for help. In fact, she couldn't have even if she had wanted to. Her 55-year-old father lost his job as a marketing manager, was unemployed for two years, and almost had to declare bankruptcy until he wiped his MBA off his résumé and got a job at a used-car dealership. Her parents no longer have any retirement money. They don't know that their daughter is receiving public assistance or that she and her fiancé can't afford to have a wedding.

While it's still too early to tell whether a significant number of young couples are delaying marriage -- the marriage rate continues to drop as it did before the economic downturn -- there are signs that couples aren't spending as much on weddings as they used to. Since Sept. 11, wedding plans have been downsized, according to Sue Totterdale, national board chairman for the National Association of Wedding Professionals. While the average American wedding costs $22,000 many couples are opting for destination weddings -- cheaper, smaller affairs that usually involve package deals in popular sunny locales like Florida or Jamaica -- that on average cost between $7,000 and $10,000. They can cost as little as $2,000 -- if the ceremony involves only the bride and groom.

But even that low price can be too much.

"We're ready to be married but we can't afford a wedding," Anna says. "I don't need a star-studded wedding and a Vera Wang dress. But we can't even afford a $300 dress and a dinner party."

These days, instead of planning their nuptials, Anna and Glenn are focused on more banal, yet pressing, concerns. They negotiate car use -- he needs their 1997 Ford Escort to drive to his part-time job at Barnes & Noble, so she often ends up walking to work. They worry about whether they can scrape together enough money for a trip to Boston for Anna's sister's graduation; they contemplate whether Glenn will have to drop out of school to work full time.

And there are murkier issues. Self-worth and economic power are intrinsically linked, and sex too.

"When I come home miserable, he won't come near me," Anna says. "The absence of sex makes you feel worse. You think, 'I got fired from my job and they don't want me, I go on interviews and they don't want me, and I come home and even my boyfriend doesn't want me."

While Anna and Glenn would someday love to have a family, the idea seems utterly impossible now, given their financial situation. Sometimes they even worry about what would happen if Anna accidentally got pregnant. "Glenn would definitely have to drop out of school to work full time," Anna says. "Or we'd have to move in with my parents. I'm not antiabortion, but having an abortion just because I couldn't afford to have a child is one of the most horrible things I can imagine having to go through."

Anna and Glenn fight in ways that in the history of their seven-year relationship, they never used to.

"When he and I fight about anything, it's about money," Anna says. "One of the big reasons I can't support myself is because I'm in a lot of credit card debt that I accumulated in college. I don't think it's fair for him to pay that. But if he wasn't paying it, the creditors would be after me. I feel miserable and I do this self-flagellation thing. And we get in fights about that because he always says, 'Why bother getting upset about it if there's nothing we can do?'"

Matthew Beckwith, 36, a former Internet executive in San Francisco, used to routinely go out for $3,000 client dinners. Then, like thousands of other young people, he got laid off. Even so, in July 2002 he proposed to Risa Evans, 31, who accepted, even though her husband-to-be not only didn't have a job but had also run out of unemployment.

"When we decided to get married, my brother thought it was a bad plan," Risa says. "He asked me, 'Why are you marrying someone who doesn't have a job?' I told him that I believed in Matt, and everything would be fine."

Matt was out of a job for two years, except for a month-long consulting gig. Ten months ago, Risa took a professionally unfulfilling job as a psychologist that had her commuting three hours a day from San Francisco to San Jose. The job left her tired, angry, and as she says, "a bad partner." The two of them live in a cramped one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco -- which Matthew says was too small for him when he was single -- overcrowded with books, the one luxury they can't bear to part with. They managed to negotiate their rent down, and they've stopped buying new clothes, even though their current threads have holes. And the couple pared down the wedding invitation list to 20 people until their parents said they'd pitch in.

Tracey L. Stulberg, a marriage and family therapist at Birmingham Family Therapy, in Michigan, says that tensions arise when the employed member of the couple feels like the partner should get a job -- any job -- instead of sitting at home in a bathrobe trolling through online listings. Lisa Bloch, 34, of Guttenberg, N.J., works for a medical publishing company. Her husband, an IT investment banker, lost his job last year. "My husband thought about doing all kinds of things and taking a job not as senior as he was," she says. "He wanted to open an aquarium store, but with stores opening and closing, I discouraged that. If it were me, I'd go work at McDonald's, but we're different people."

Risa says that in the past she's taken her doctorate off her résumé and gotten retail jobs. But for Matthew, she thinks taking a job at, say, Starbucks would probably just make him feel worse, as if everything he'd spent 12 years working for had been a big waste.

Even with their sincere efforts not to blame each other for the horrible state of their financial affairs, Risa says that sometimes, while helping Matthew prepare for interviews, she ends up being sharper and more accusing than she wants to be. "He gets this look on his face and I know I'm going somewhere bad."

Matthew says he can't deny that his money woes affect how he feels about his role in the relationship. "I think of myself as enlightened," he says. "But there's still the male thing, that you're supposed to provide. There are lots of things that I'd like to do for Risa" -- like taking her on vacations or to nice restaurants -- "but I can't."

Risa insists that she's fine with Matthew's inability to do those things for her right now, and they say that their hardships have made their relationship stronger than ever. But when Matthew finally gets a new job, Risa, a former shoe addict, has one request.

"A pair of Jimmy Choos," she jokes. "Choos cost $500, and if we can afford them one day, I know everything will be fine."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Rachel and Rich (neither wanted their last names published) met in a chat room almost three years ago. At the time, Rachel was living in Youngstown, Ohio, and Rich was working in New York City as a network engineer consultant. Their long-distance relationship was filled with vacations and shopping adventures; on Rachel's 21st birthday, Rich even took her and a friend to Amsterdam. At the time, Rachel was working as a telemarketer and suffering from debilitating panic attacks. Rich simply offered to pay her bills while she took some time off.

"Our upbringing was different," Rachel explains. "My mom, who works at a GM auto factory building harnesses, was a single mother. If I wanted money, I had to have a job. Rich's family was more well off. It was a shock to me that this person would pay my bills. But it made it possible for us to do things and have fun."

When they spoke to Salon, they had $8 in their bank account.

Rich was laid off from his job as a network engineer in January 2001. Two months later, he moved to Ohio to be with Rachel while she finished college. Last September they got engaged and spent $3,000 of Rich's savings to furnish their $510-a-month apartment. All those savings are gone.

Since graduating from college last spring, Rachel, who sat at the computer for hours every day looking for work, only just a few weeks ago managed to find a job as a telemarketer. Rich is working an entry-level technical support job, making half of his former salary, even though he has eight years' experience in the field. Rachel has maxed out one credit card, and Rich has maxed out three. "I never thought we'd have to go through this," Rich says. "Or at least I didn't think it would last this long." These days, they don't bicker over what movie to rent -- they try to figure out if they can afford to rent one at all.

"When he was unemployed, he would stay in bed all day," Rachel says. "He doesn't smile like he used to. Sometimes it's so severely depressing in this house that I don't want to be here. We fight a lot about the bills. I want to get them in on time but we can't always do that, so we fight about whose credit will be ruined." Lately, Rachel's self-esteem has plummeted. She's gained 50 pounds but can't afford to join a gym to work some of it off.

"I understand that she's down because of the economy, but she'll get a job eventually," Rich says. "There's no point looking at it any other way. It just makes you feel worse."

Rachel has a harder time keeping that kind of perspective. She admits that not only does she beat up on herself, but that she'll pick at her fiancé as well. She doesn't think he's searching hard enough for a better, higher-paying job.

"I want to say to him, 'You always say you're going to look for something and you don't,'" she says. "But I can't say anything, because I don't have a job." Rachel's anxiety and anger has also found its way into the bedroom.

"We had sex today for the first time in a couple months," she says. "I don't feel pretty. I don't have a job and I wasn't having sex -- I felt like I wasn't doing anything right."

Stulberg says that sex is often the first thing to go when couples are having problems.

"Sex? No way!" Stulberg says. "If you can't afford to put food on your table and you're angry at each other, you're not going to bed together."

Rachel used to see a therapist -- which her mother's health insurance covered until Rachel graduated from college and was kicked off the plan -- and sometimes Rich went with her. They both said it helped. But now, without professional help, they both say it's a constant balance between the emotional trauma and the practical realities. Often it seems that if they just had more money, they wouldn't fight so much. One solution would be to get help from their families, but that's not simple either.

"I already have $30,000 in school loans and my dad can't help pay for it like he was supposed to," Rachel says. "We have to borrow money from Rich's family. I hate it. It makes me feel like a piece of shit."

And as with any couple suffering from financial problems, it's the big, often necessary purchases that stir up debilitating anxiety. For Rachel and Rich, the wedding is causing the most strain.

"We got in a really bad fight a couple of weekends ago -- he left the house," Rachel says. "He says, 'How can you even think about a wedding when we can't pay our bills?' Now I'm scared to bring it up."

Rachel and Rich try to do activities and make small purchases to make them feel better. "We do things to try to keep it fun," Rachel says. "He hates going shopping with me because he can't buy me things like he used to. I think that made him feel manly." A few weeks ago Rachel bought a CD, the first one she'd purchased in months. "I wanted it so bad," she says. "And Rich said 'Just get it!' And so I did."

Interestingly, none of the young couples interviewed by Salon blame anyone -- not Wall Street, not George Bush, and most of the time, not each other -- for their financial straits. They want to fix their problems themselves. While that creates more pressure on each other, chances are that when they pull out of the recession cloud, they'll be able to say they did it on their own.

Someday it will be a good story to tell the kids.

Shares