America is in the midst of a controversial, undeclared war in a distant land against a cunning and resourceful enemy. The nation is bitterly divided. Opponents of the war say that our leaders manufactured a bogus threat to justify an unnecessary and unwinnable war that is inflaming the world against us. Supporters say that a strong American stand is necessary to stop an insidious, totalitarian ideology from spreading across a strategically vital region and proclaim that the encounter is nothing less than a clash of civilizations. Despite overwhelming American military superiority, the war drags on and on. Flag-waving supporters of the administration clash with dissenters, calling them traitors. High-ranking government officials say that those who criticize the war are giving aid and comfort to the enemy. Obsessed with secrecy and convinced of the rightness of his cause, the tough-talking Republican president vows to stay the course.

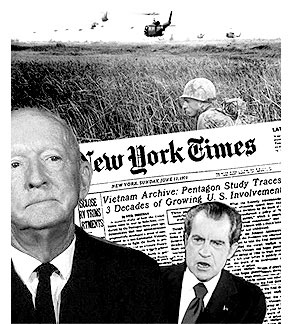

2003, George W. Bush, and the war on Iraq? No: 1971, Richard M. Nixon, and the war in Vietnam. But if the similarities between the two periods are striking, what happened next has no parallel today. At least not yet.

An explosive document is leaked to the press. The papers, drawn from top-secret government files, reveal embarrassing things about the administration’s conduct of the war, including the fact that U.S. officials knew that many of the official reasons given to support the war were false. The government sues to stop the press from publishing the document, saying that publication threatens national security. The case goes to the Supreme Court, which hears the case with extraordinary speed. In a passionate and contentious ruling — one in which, extraordinarily, all nine justices feel compelled to write opinions — the court rules, 6-3, that the government has no right to prevent the press from publishing the papers.

The Pentagon Papers case was a landmark ruling for press freedom and a historic rebuke of government’s attempt to suppress it. But it is a fragile ruling. Americans like to think that the freedom of speech guaranteed them by the Bill of Rights, and the Supreme Court rulings upholding that freedom, are written in stone. Nothing could be further from the truth. As Justice Brennan wrote in an earlier free speech case, “It is characteristic of the freedoms of expression in general that they are vulnerable to gravely damaging yet barely visible encroachments.” Those encroachments threaten free speech at all times — and during war they become extreme. Civil liberty, in particular the right to free speech, is often curtailed during wartime, when fear, patriotism and the siren song of “national security” combine to overpower what can be seen as a dispensable luxury. Later, when the smoke has cleared, the attack on speech is seen as embarrassing and the laws are removed from the books — until the next war.

A close look at the court’s ruling itself, and American history both before and after 9/11, show that the right of the press to publish freely can never be taken for granted. There is reason to suspect that if a case similar to the Pentagon Papers were to come before the high court today, a very different ruling would result. And if President Bush succeeds in naming more right-wing justices to the court, that possibility would grow stronger still.

The list of America’s shameful wartime retreats from civil liberties is long and starts even before the founding of the republic: during the Revolutionary War, New Hampshire declared that believing in the authority of the king of England was treasonous. President Lincoln suspended habeas corpus and seized the telegraph lines. World War I saw perhaps the worst assault on civil liberties, most notably the infamous Sedition Act of 1918, which forbade “[u]ttering, printing, writing, or publishing any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language intended to cause contempt, scorn … as regards the form of government of the United States.” So extreme and hysterical was the World War I era’s attack on free speech that it spurred the courts, which throughout the 19th century rarely dealt with issues arising from the Bill of Rights, to a series of rulings that essentially created America’s uniquely far-ranging body of civil liberties law.

In World War II, Japanese-Americans were sent to concentration camps simply because of their ethnicity. And after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, a shellshocked Congress approved the USA PATRIOT Act, which expanded federal power and eroded privacy and equal protection freedoms in a number of areas. To this day, hundreds of individuals who have never been charged and whose identities have not been released are being held in harsh prisons without constitutional rights, while the government exercises greatly expanded wiretapping and surveillance powers. The Bush administration asked news organizations not to run videos released by Osama bin Laden, dubiously claiming that they might contain secret messages to terrorists: The media dutifully complied. Perhaps most chillingly, political protest — the single type of speech the Founders were most concerned to protect — has come under legal attack. A South Carolina man was charged with the federal crime of threatening the president’s safety simply for holding a sign that read “No Blood for Oil” outside the locale of a Bush speech. Few have protested these measures.

In all of these cases, attacks on the First Amendment have been justified by “national security.” Today, with the apparently eternal “war on terrorism” creating a quasi-permanent national security crisis, that argument may carry even more weight, as the courts grapple with the problem of how to balance the right to free speech with the executive branch’s right to secrecy. As the Supreme Court’s historic ruling Thursday overturning Texas’ inhumane and outmoded sodomy laws showed, courts do not operate in a social vacuum; and after one of the few large-scale foreign attacks ever carried out inside the borders of the United States, with the public fearful and an already-secretive administration demanding a blank check to fight terrorism, courts are more likely to defer to executive branch arguments that national security is at stake — as indeed they have repeatedly done in civil liberties cases arising from 9/11.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The Pentagon Papers came into being because of Robert McNamara’s angst. The chief architect of America’s Vietnam policy, an ardent anti-communist who helped formulate the administration’s doctrine that the Red menace had to be rolled back in Southeast Asia lest it spread throughout the region, McNamara gradually began to realize that the war could not be and indeed could never have been won. Stricken by guilt, in 1967 McNamara commissioned a study of how the U.S. came to be in Vietnam. The study, titled “History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy,” was 7,000 pages long and filled 47 volumes. It provided support for several positions that antiwar critics had long asserted: that Viet Cong leader Ho Chi Minh — America’s former ally in World War II — was regarded as a nationalist hero throughout the country; that the U.S.’s desire to crush the communist North was largely responsible for the breakdown of the 1954 Geneva settlement for Indochina; that in 1965 South Vietnamese President Thieu had said that the communists would likely win any election held in the country; and, most significantly, that American officials realized fairly early that the war could not be won militarily, but kept the war going anyway.

In short, McNamara’s study supported the position that what was really going on in Vietnam was a war of national liberation, not the rise of a dangerous communist menace bent on exporting ideological mischief. More, it made clear that at a certain point America’s leaders continued the war not to contain communism but because they didn’t want to lose face by being defeated — even though they knew they couldn’t win. None of these things, of course, was revealed to the American people.

The Pentagon Papers were leaked to the New York Times and the Washington Post by a former hawk turned dove, Daniel Ellsberg, who had worked on the study for the RAND Corp. Ellsberg faced 115 years in prison for his act. But he hoped that by putting the papers in the hands of the press he would convince the U.S. to pull out of Vietnam. He was wrong: Nixon mined Haiphong harbor soon afterward, and Americans fought in Vietnam for two more bloody years. Their publication did, however, lead Nixon to create a team of so-called plumbers to make sure there were no more “leaks” — and when the plumbers bungled their way into a place called the Watergate, they set in motion a train of events that eventually drove their vindictive, paranoid leader from the White House in disgrace.

After protracted study of the documents and contentious internal deliberations, the Times — which had been increasingly critical of the Vietnam War — published the first installment of the massive study on Sunday, July 13, 1971, under the cautious headline “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.” At first, Nixon was unconcerned, believing that the purloined papers would be more embarrassing to Kennedy and Johnson than to his administration. But national security advisor Henry Kissinger convinced him that he should fight the publication. (According to David Rudenstine, author of “The Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers Case,” Kissinger even went so far as to tell him that his failure to take action “shows you’re a weakling, Mr. President.”)

In the debate over what to do, Nixon chief of staff H.R. Haldeman summed up the impact of the papers with admirable prescience: “But out of the gobbledygook, comes a very clear thing: [unclear] you can’t trust the government; you can’t believe what they say; and you can’t rely on their judgment; and the — the implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the President wants to do even though it’s wrong, and the President can be wrong.”

After the Times had published two excerpts, Attorney General John Mitchell sent a telegram to the paper, asking it to stop publishing the material and warning it that disclosing information that could jeopardize the security of the country was illegal and could result in a 10-year sentence. The Times refused. The government then asked for a temporary restraining order in a district court in New York.

By chance, the judge was a Nixon appointee, Murray I. Gurfein, who was sitting on the bench for the first day. Judge Gurfein ruled against the government — and he did so with words of rare forcefulness and eloquence. “The security of the Nation is not at the ramparts alone,” Gurfein wrote. “Security also lies in the values of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.”

The government appealed to two circuit courts — by now the Washington Post had begun publishing summaries of the material, further complicating the case — one of which ruled against it, one for it. The Supreme Court granted certiorari (i.e., agreed to hear the appeal) on June 25, issuing a temporary stay that halted publication while it heard the case. The case, like Bush vs. Gore, moved with lightning speed: The Court heard arguments the next day and issued its ruling — New York Times Co. vs. United States — on June 30. The entire case took only 18 days from first publication to final ruling — one of the fastest resolutions of a major case in U.S. history. This extraordinary speed bears witness to the seriousness with which the court regards governmental attempts to impose so-called prior restraints on the press, and its awareness that such cases must be resolved quickly.

If the Pentagon Papers were published, White House lawyers warned, America’s security would be gravely imperiled, in part because other nations would be reluctant to deal with us if they thought their conversations would be revealed. Against this argument, the Times lawyers invoked constitutional bedrock, one of the principles upon which the United States is founded: Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press …”

In one of the most anticipated rulings in court history — 1,500 people lined up for the court’s 174 seats — the court ruled for the Times and against the government. In his passionate opinion for the majority, rightfully considered one of the great affirmations of the First Amendment in U.S. history, Justice Hugo Black excoriated the administration for bringing the case. “[F]or the first time in the 182 years since the founding of the Republic, the federal courts are asked to hold that the First Amendment does not mean what it says, but rather means that the Government can halt the publication of current news of vital importance to the people of this country. In seeking injunctions against these newspapers and in its presentation to the Court, the Executive Branch seems to have forgotten the essential purpose and history of the First Amendment … I can imagine no greater perversion of history.”

The elderly justice from Alabama had overcome his youthful Ku Klux Klan membership and earlier legal missteps — he upheld the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II — to become a great jurist, an immovable opponent of McCarthyite hysteria and perhaps the most powerful defender of the First Amendment in court history. Black was in poor health, suffering from severe headaches: He died only three months after the case was decided. But at the end of his life, there was still power in the aging lion’s legal claws — and he used them to smite the executive branch that had tried to muzzle the press.

“In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy,” Black thundered. “The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.”

And then Black penned a line that has become one of the most famous in Court history — and echoes powerfully today, as the controversy simmers over Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction: “And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.”

In today’s climate of acquiescence to the commander in chief, when the establishment and much of the country apparently finds the idea that the president could have lied to the country too frightening or unseemly to entertain, it is difficult to imagine a Supreme Court justice flatly accusing the government of lying about why it sent American troops “off to foreign lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.” But Black had actually wanted to use still stronger language. As Roger K. Newman recounts in his biography of the justice, while working on his opinion, Black woke up his wife, Elizabeth, in the middle of the night and asked her: “How would it be if I said that the press should be free to prevent presidents from sending American boys to foreign lands to be murdered?” She wisely told him she thought that would be a bad idea. So instead, in a twist of historic irony, he drew inspiration from one of his favorite songs, a fire-breathing old Southern ditty called “I Am a Good Old Rebel.” “Three hundred thousand Yankees lie stiff in Southern dust/ We got three hundred thousand before they conquered us/ They died of Southern fever, Southern steel and shot/ And I wish it was three million instead of what we got.” Black had formerly sung the song to friends and family, but stopped when George Wallace started fighting integration. Now he made use of the old Confederate song to defend the right of the press to reveal information about a war he opposed.

Black held no particular affection for the press itself. It was freedom he cherished — the freedom to speak that he believed the Founding Fathers had granted Americans in perpetuity and virtually without exception, freedom that he wrote was the last best check against governmental tyranny. Which makes his extraordinary tribute to the Times and the Post doubly meaningful: “In my view, far from deserving condemnation for their courageous reporting, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other newspapers should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly. In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam war, the newspapers nobly did precisely that which the Founders hoped and trusted they would do.”

At issue in the decision was prior restraint — the power of the state to prevent the press from publishing something, as opposed to punishing it after it has published. One of the seminal Supreme Court cases involving prior restraint was a 1931 case, Near vs. Minnesota. Minnesota courts had enjoined a scandal sheet called the Saturday Press from publishing future issues. Chief Justice Hughes reversed, stating that the “chief purpose” of the First Amendment was to prevent prior restraints on publishing and making it clear that after-publication punishment was greatly preferable. This and other legal precedents imposed what the court called a “heavy presumption against [the] constitutional validity” of any governmental attempt at prior restraint and thus a “heavy burden of showing justification for the imposition of such a restraint.”

But Near vs. Minnesota also contained a brief passage that included a potential exception, on grounds of national security, to its ruling against prior restraints. Writing that the “protection even as to previous restraint is not absolutely unlimited,” the court said that the “government might prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops.”

The issue of national security would weigh heavily on the minds of at least five of the justices — and contribute to deep divisions not only between the six justices who voted with the majority and the three who opposed, but within the majority itself.

Six justices — Black, Douglas, Brennan, Marshall, Stewart and White — found that the United States had not met the heavy burden required to impose prior restraint. But the number is misleading: In fact, the consensus was extremely fragile. This is reflected in the fact that the ruling itself was extremely brief, said almost nothing substantive and was handed down per curiam, or “by the court,” rather than as an opinion written by a justice speaking for the rest of the majority. The fact that the ruling was issued per curiam reflected the fact that although the majority agreed that the government had not met the burden of justifying prior restraint, no five justices could agree on why it had not. As for the ruling itself, it was remarkably terse: It merely recited the precedential boilerplate that prior restraints come with a heavy presumption against their constitutional validity, and then added, “We agree.” As First Amendment expert Rodney A. Smolla points out in an illuminating study of the case in his excellent book “Free Speech in an Open Society,” “It is difficult to imagine an opinion of the Supreme Court in a landmark case saying less.”

The court’s inability to say anything substantive — an inability that severely limited the case from serving as a precedent in future decisions — clearly proceeded from the deep split within the majority. Only two justices, Black and Douglas — the two most noted First Amendment “absolutists” in court history — took the position that prior restraints could never be justified. A third justice, Brennan, allowed that there might in extremely rare circumstances be a national security exception, but he made it clear that the executive branch would have to come up with hard proof of immediate harm, not vague assertions. Justice Marshall steered a middle course.

The “absolutists,” Black and Douglas, argued that the court should not even have heard oral arguments in the case — it should have simply entered a summary judgment against the government. As Black wrote, “I believe that every moment’s continuance of the injunctions against these newspapers amounts to a flagrant, indefensible, and continuing violation of the First Amendment.”

On the opposite side of the spectrum, three justices — Chief Justice Burger, Harlan and Blackmun — dissented, arguing that the First Amendment’s protection of speech was limited by another equally compelling interest, what Burger called “the effective functioning of a complex modern government and specifically the effective exercise of certain constitutional powers of the Executive. Only those who view the First Amendment as an absolute in all circumstances — a view I respect, but reject — can find such cases as these to be simple or easy.” The dissenting justices argued that the court had heard the case in “irresponsibly feverish” haste, making it impossible to determine whether the documents would actually harm national security. And in the dissenters’ view, the executive branch’s right to conduct foreign policy carried far more weight than the majority allowed.

Just as Black had issued a remarkable, personal rebuke of the executive branch, so Chief Justice Burger singled out the New York Times for harsh moral criticism. “To me it is hardly believable that a newspaper long regarded as a great institution in American life would fail to perform one of the basic and simple duties of every citizen with respect to the discovery or possession of stolen property or secret government documents. That duty, I had thought — perhaps naively — was to report forthwith, to responsible public officers. This duty rests on taxi drivers, Justices, and the New York Times.” In sharp distinction to Black, who stated that the press’s role was to “censure” the government, Burger argued that the Times, rather than disgracing itself by receiving stolen goods, should have played ball with the president — what Smolla calls a “we’re all in this together” position. In Burger’s view, the press should work together with the executive branch — which Burger implicitly argued could be trusted to behave honorably and honestly — to determine whether national security was in danger.

That today Burger’s position is more accepted and observed by the press itself than by the court is a development that does not bode well for those who share the Founders’ views that a fair but independent and even adversarial press is the best bulwark against governmental abuse.

The dissenters took very seriously the government’s claim that national security could be compromised. Ominously, Justice Blackmun closed his dissent by writing, “I hope that damage has not already been done. If, however, damage has been done, and if, with the Court’s action today, these newspapers proceed to publish the critical documents and there results therefrom ‘the death of soldiers, the destruction of alliances, the greatly increased difficulty of negotiation with our enemies, the inability of our diplomats to negotiate,’ to which list I might add the factors of prolongation of the war and of further delay in the freeing of United States prisoners, then the Nation’s people will know where the responsibility for these sad consequences rests.”

But it is the opinions written by the two justices who voted with the majority, but disagreed with their four brethren about the reasons, that truly reveal the fragility of the ruling. Justices White and Stewart both wrote that if Congress had passed specific and limited legislation upholding the government’s right to prior restraint in such cases, they might have upheld the lower court’s injunction. White wrote, “I do not say that in no circumstances would the First Amendment permit an injunction against publishing information about government plans or operations. Nor, after examining the materials the Government characterizes as the most sensitive and destructive, can I deny that revelation of these documents will do substantial damage to public interests. Indeed, I am confident that their disclosure will have that result.”

White was wrong. The real-world consequences of the publication of the Pentagon Papers (not just the Times and Post but other publications also ran excerpts or synopses) vindicated the court’s decision and undermined the arguments of those who said that publication of the papers would damage the public interest. The near-consensus among scholars and analysts is that the publication of the Pentagon Papers only embarrassed the government — it did not damage America’s security. Like the boy who cried wolf, the Nixon administration’s heavy-handed invocation of national security only succeeded in raising skepticism about this all-too-convenient recourse of the executive branch — and at least for a time, perhaps, tilted public, legislative and ultimately judicial opinion away from deference to such claims.

But the fault lines running beneath the court’s murky decision remain, and could crack open at any time.

In one sense, that is as it should be. There is not, nor should there be, an unlimited right to free speech. As Justice Blackmun noted in his dissent, “First Amendment absolutism has never commanded a majority of this Court.” The notorious case cited by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes of someone falsely shouting “fire” in a crowded theater is the most obvious type of unprotected speech. Others include obscenity, false commercial speech, incitement to unlawful behavior, and defamation of a private person. But of all these exceptions to First Amendment protection, executive-branch claims of national security are perhaps the most difficult to evaluate, and thus reveal the most about justices’ attitudes toward free speech and the state — not just its right to suppress speech but its trustworthiness. Such claims pose a difficult question: Do the press’s right to publish, and the public’s inherent right to know, as a matter of principle outweigh generally untestable governmental claims that publication will harm national security?

For conservative jurists, this question throws into sharp relief the same tension or ambiguity that besets conservative politicians: the schism between a libertarian ideology rooted in Jefferson, Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill and an authoritarian ideology rooted in Christianity, nationalism and patriarchy. Whenever a judge is torn in two directions, the decisive factor is often his or her attitude to the parties or concepts involved in the dispute — whether a given administration, a war, or the notion of free speech.

(The case of Justice Scalia vividly illustrates this point. Scalia bitterly opposed the court’s landmark decision last week striking down Texas’s sodomy statute, arguing that the majority overreached the law in their desire to accommodate the “so-called homosexual agenda.” But Scalia himself has not been averse to bending the rules in a far more troubling way — and departing from his entire previous judicial philosophy — to accommodate the more immediate agenda of putting a fellow right-winger in the White House. Just as Scalia’s lofty arguments about judicial restraint proved dispensable when Gore was threatening to become president, so his rage at the Texas ruling proceeds more from his deeply rooted belief that gays do not deserve the transcendental, historic rights the court saw fit to give them, than any grand principle.)

The Pentagon Papers case did create a precedent in support of free speech. But it is a murky and shaky precedent, subject to the vicissitudes of history, the willingness of future justices to defer to the executive branch, and the tough-mindedness of journalists. (That governments will continue to use national security to attempt to restrict civil liberties is a foregone conclusion.) And optimism is not warranted.

Justice Black’s argument that the public has the right to all information, because only the marketplace of ideas assures the security of the nation — a notion that ultimately goes back to John Stuart Mill’s “On Liberty” — may have resonated for the Founders, but it is increasingly out of step with our security-obsessed age. Today, when the president’s spokesman tells us we should “all watch what we say,” John Ashcroft is in charge of law enforcement and the PATRIOT Act in force, Black’s statement that “the guarding of military and diplomatic secrets at the expense of informed representative government provides no real security for our Republic” sounds positively radical.

History shows that governmental claims that unfettered press freedom will harm national interests are unfounded. Transparency is a virtue the civilized world rightfully insists is a prerequisite for good governance. The United States has long been the world leader in free speech. Even now, during the endless “war on terrorism” — especially during that war — it must continue to practice what it preaches.

The moral of the Pentagon Papers case is that constant vigilance in defense of the First Amendment is necessary — all the more so, as Chief Justice Hughes wrote many years ago, in time of war. The six justices who stood up to a sitting administration during wartime were the last line of defense against the unwarranted use of governmental power. There were powerful forces pulling at them: the siren songs of flag and war, the power of the presidency. But, though divided, they did not abandon their posts. And by so doing, they provided a signpost and a beacon for all Americans, who, in an age of fear, need to be reminded that presidents come and go, wars come and go, but the right of the press to publish, and the people to know, must not be allowed to perish.