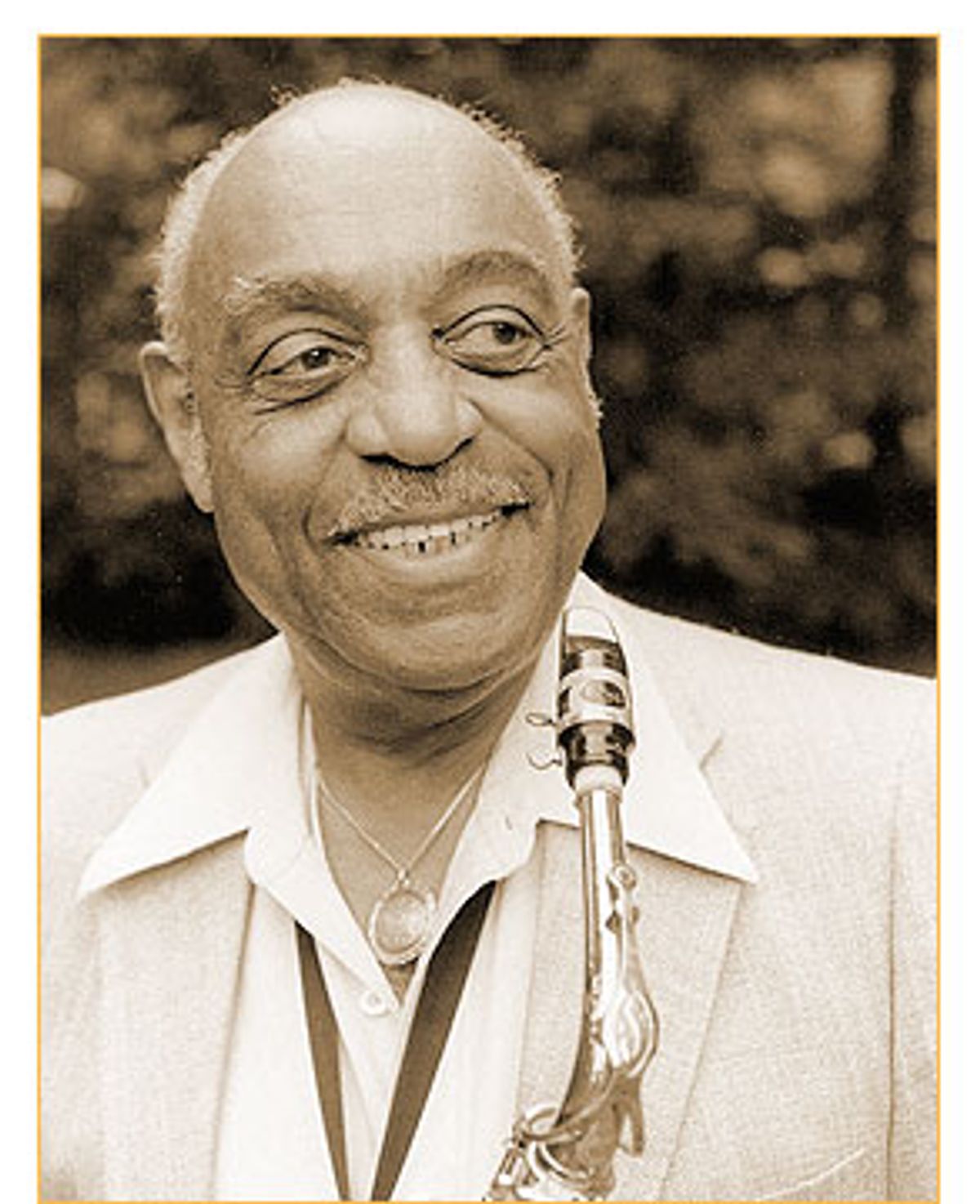

"It's better to be a legend than a myth." So said Benny Carter, the Apollonian of jazz, who died on July 12 at age 95. Carter had a 75-year career as an instrumentalist, arranger, composer and big band leader. Almost unbelievably, he began recording in 1928 and didn't stop until 1996. Raised in New York's San Juan Hill neighborhood, near what is now Lincoln Center, he was a founding father of the swing era, and remained in the jazz elite for the rest of his life. Nobody in the history of jazz ever did as many things as well. His music and life had a balance among lyricism, serenity and drive.

Carter was a peerless technician with a fluid sound. Along with Duke Ellington's sideman Johnny Hodges, he created the template for the jazz alto saxophone in the 1930s. Unlike Hodges, he also turned himself into a major jazz trumpeter, recorded on five other instruments, sang the occasional vocal and wrote more than 200 tunes -- and sometimes the lyrics for them. Carter was mostly self-taught. As a young player, he bought stock band arrangements and laid them on the floor to figure out how scores were put together. By 1930, according to jazz historian Gunther Schuller, he was the man that other jazz arrangers were following. With the rest of the swing generation, he helped change the clunky Western sense of musical time into something lighter and more surprising, and did it with a sophistication matched only by that other master of broken rhythms, Fred Astaire.

His arranging style, displayed on "Symphony in Riffs" (1933), laid down the big-band template of contending reed and brass sections. The saxophone section charts were based on his solo alto style, featuring long, sinuous lines played in harmony. Unlike Ellington's early arrangements, which focused on color at the expense of rhythmic movement, Carter's swung. And he anticipated later harmonic trends, like bebop's famous flatted fifth chord interval.

Carter's influence may have limited his success as a big band leader, since variations on his work were everywhere. But that iconic swing sound meant that his composing and arranging talents were in demand, from the BBC dance orchestra, during a mid-'30s European sojourn, to the American big bands when he returned before World War II. Hollywood called, beginning with his arrangements for the all-black musical "Stormy Weather" in 1943, and Carter became one of the first African-Americans to integrate the Hollywood studios. There's a glimpse of him in "An American in Paris" (1951), performing an alto solo on "Someone to Watch Over Me" during the cafe scene where Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron first meet. In addition to arranging for 33 movies and 20 TV series, Carter wrote huge numbers of vocal arrangements for top singers. In big-band settings, Ella Fitzgerald was often imprisoned by the soporific pop sound of her "Songbook" albums; in "30 by Ella" (1968), Carter's shifting medley arrangements freed her to improvise. Sarah Vaughan, whose two Carter albums are available as "Sarah Vaughan: The Benny Carter Sessions" (1962-63), once took a blindfold test to identify a recording. She couldn't identify the singer, but instantly recognized that it was a Benny Carter arrangement.

To keep up with the latest trends for Hollywood, Carter needed a capacity to change. Many star swing-era bandleaders, such as clarinetist Benny Goodman and vibraphonist Lionel Hampton (and even Louis Armstrong in his trumpet work), remained wedded to the styles that had made them famous -- they played for the nostalgia market. While the big stars sounded dated after bebop arrived in the mid-1940s, major swing soloists with less pop success, like Carter, tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and trumpeter Roy Eldridge, adjusted. To remain relevant to jazz audiences, they incorporated bebop's offbeat rhythms and more dissonant harmonies into their swing base, producing a hybrid that let them work with younger players, and that remains fresh 50 years later. Even in his last years, Carter remained open to new sounds. He liked avant-garde trumpeter Dave Douglas, and once telephoned the innovative post-swing singer Lea DeLaria out of the blue to compliment her on a radio performance.

In a music that often venerates tragedy, angst and pretension -- think Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Wynton Marsalis, respectively -- Carter's sunny spirit stood out. The bubbling "Pick Yourself Up" on the album "Cosmopolite" (1952) transforms his knotty rhythms into a clarion call celebrating resilience. Carter's ballad work was reflective, as on his composition "Blue Star" on "Further Definitions" (1961), where the tension between the solos and the lush saxophone choir communicates loss and yearning. But he rarely plumbed the depths of despair.

Carter's restraint led to the cliché that his playing was suave. This had a measure of truth -- he did albums titled "The Urbane Sessions" (1952-55) and "A Gentleman and His Music" (1985). In his personal life, he was erudite, overcoming, through force of will, an eighth-grade education. Carter developed an eye for African and African-American art, with a special fondness for Romare Bearden, though he characteristically denied any special expertise. Frighteningly sharp until the end, in his last months he was working through David McCullough's biography of John Adams. Carter's aplomb was unfailing. When a longtime fan talked of enjoying music by "you boys" back in the 1930s, rather than acting offended, Carter deflected the comment by asking, "And how much older am I than you?" (The answer turned out to be several years.)

As gracious and warm as Carter was, he was also driven. He needed to be, to deal with life on the road during segregation, spearhead the integration of the black and white musicians' unions in 1950s Los Angeles and succeed in the studios. An arranger had to be fast and service-oriented -- if you turned down one assignment, the client might not give you another. A tenor saxophonist and arranger from a later generation, Benny Golson, said that when he quit the studios to return to jazz, it felt like manumission. Given the press of Carter's arranging work from the late 1940s through the 1960s, he limited his public appearances to occasional Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts, but continued to lead some albums as an instrumentalist and composer. In later years, when he visited New York as a performer, he was always scrambling to complete arrangements for the next concert or recording session.

His move back to performing was partly Hollywood-driven. Studio work began to dry up in the 1970s, as rock displaced jazz and singers like Fitzgerald lost their mass-market record sales. Successful enough to have a house in the hills above Los Angeles, Carter could have gone into comfortable semi-retirement. But while jazz often ignores performers in mid-career, it promotes players over 70 as "legends." For the first time, Carter had hit a P.R. sweet spot, and he made the most of it. In the early 1970s, Princeton professor Morroe Berger organized a series of workshops and concerts for Carter at the university. By mid-decade they had morphed into a touring schedule that would take him around the world.

In 1976, as he approached the magic age of 70, Carter did his first album as a leader in 10 years. Playing what he liked, and acclaimed by the jazz public for it, he went on to lead 26 more big band and small group albums before retiring in 1997 at age 90. Few jazz musicians were as prolific in those years. In the late 1940s, it looked like bebop revolutionary Charlie Parker had passed him as the leading alto man, but Carter's resurgence made him more current than Parker, who had died young and recorded few LPs with modern sound quality. Ironically, the one Parker album that has remained central to the repertory, judging from radio airplay on WBGO, the New York metropolitan area's leading jazz station, is "The Charlie Parker Jam Session" (1952), a head-to-head-to-head between Parker, Carter and Johnny Hodges that displays their distinct styles at a peak.

Carter's playing retains its youthful buoyancy on "Central City Sketches" (1987), which marked his first American big-band album in 20 years, updating arrangements of older compositions and including the shimmering new six-movement title suite. He thickened his tone and simplified his rhythmic filigrees, which may have been concessions to both the newer hard bop sound and his distaste for long hours of daily practice. (Like Boston Celtics great John Havlicek, Carter had the gift of getting into playing shape quickly.)

After he turned 80, he used fewer fireball tempos and more sustained notes, which he shaded dynamically and tonally to convey emotion and build rhythmic tension. Carter avoided the modern tendency to play chord changes like a sewing machine -- the melody still shone through. The Grammy-winning "Elegy in Blue" (1994) vibrantly reworked the signature tunes of departed jazz greats, but it depressed Carter, by reminding him of all the contemporaries he had outlived. In the final years of his career, his tone became drier and his phrases shortened, but he remained adventurous. His last CD, "Another Time, Another Place" (1996), features an up-tempo, nearly unaccompanied alto duet with Phil Woods on "Speak Low" that would have made many younger players implode. At age 89, he flew to Thailand to play a command performance for King Bhumibol (an amateur jazz saxophonist).

Carter lived for whatever he was doing next. His Los Angeles house had a wall full of awards that spilled out onto nearby tables, including the Kennedy Center Honors and the National Medal of Arts, but he resolutely refused to dwell on the past. I talked with him regularly in his last years, and everything I learned about his era I learned from books. (These included the excellent Carter biography by Morroe Berger, Ed Berger and James Patrick, who somehow got him to reminisce.) Once, at a Lincoln Center tribute concert, Wynton Marsalis dredged up a 1930s Carter composition that its author couldn't remember. "At my age you start forgetting things," Carter said. "It's the things I want to forget and can't that are the problem."

Carter is an immortal in jazz, and by living to 95 in good health he even came close to that in the real world. But while mortality catches up with all of us, Carter's wit, elegance and propulsion live on, burnishing the American spirit.

Shares