"Pulp Art: Vamps, Villains, and Victors from the Robert Lesser Collection," at the Brooklyn Museum of Art through Aug. 31, fairly sings with what Nabokov called the exhilaration of Philistine vulgarity.

It's not seeing these works of eminently disreputable beauty in a bona fide art museum that's thrilling (like watching the Marx Brothers demolish "Il Trovatore" in "A Night at the Opera") but the works themselves. The show is a trove of oil paintings that adorned the covers of pulp detective and western and sci-fi magazines -- illustrations that have bled into our subconscious through reproductions and imitations, representing one of our most fragile pop-culture artifacts.

It's estimated that less than 1 percent of all the paintings done in the heyday of the pulps have survived. Robert Lesser, the collector from whose collection the Brooklyn exhibit has been culled, owns about 750. There are other collectors, but the stories of the paintings that didn't survive are sad ones. A fire at the Bronx warehouse of Popular Publications destroyed that company's collection. More telling is what happened when, in 1961, Condé Nast acquired the pulp publisher Street & Smith. Cramped for space in its new digs, the publisher contacted artists about reclaiming their work. Most said no. An auction failed to attract any bids. Condé Nast employees turned down the chance to take the paintings home for free. Finally, Street & Smith's enormous trove, maybe the largest collection of pulp art in existence, was literally hauled to the curb.

In his book "Pulp Art," Lesser answers the question "Why?" For the purposes of this piece, the reasons Lesser provides are an implicit answer to the question of what pulp art has to do with sex. "Pulp art," Lesser writes, "is, to many, offensive art ... Your spouse and other family members would balk at hanging it in the house: the neighbors might see it and it's not nice." (In fact, Lesser told me at the exhibit that he met the daughter of a pulp artist who has saved her father's canvasses in her attic. When he asked her why she didn't display them, she told Lesser the ladies from her church would disapprove.) "Landscapes, seascapes, a bowl of fruit, a vase of flowers, a dog or a cat or a horse, an emotionless canvas of abstract colored shapes, and Norman Rockwell's 'Saturday Evening Post' paintings are nice."

I'd argue that Rockwell is a more complicated case than Lesser implies -- especially his later work of a little black girl being escorted to school with the graffito "Nigger" clearly visible on the wall behind her, or the painting inspired by the Freedom Summer murders of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney -- but I take his point in terms of Rockwell's reputation.

That simple but undeniable explanation of why so much pulp art was junked, and the fact that even many of the artists were embarrassed by this work, is the same explanation people would give for not hanging a piece of erotic art in their house, or for even admitting to an interest in the erotic. Like porn and erotica, pulp art does not reach the "nice" areas of our brain. It aims for the gut and the groin, awakening our unacknowledged fantasies, creating the immediate need to possess the object in view, to devour the secrets it promises, assuring us that this visual tease only hints at what's inside. In that way, the covers of pulp magazines functioned as the box covers of porno tapes and DVDs do now (which is why porn producers spend so much time and money on the box cover).

Parents, ministers and the clergy may have characterized pulp as the equivalent of a dark stranger crooking his finger and luring you into a path of vice, but the visual and visceral impact of the covers really did operate like an unsavory come-hither. It's not hard to imagine respectable people surreptitiously buying pulp magazines at the newsstands in the same way that people buy skin mags today.

There is, of course, a line that the pulp magazines would not cross and that, in the '50s, EC comics, with their covers of dismembered limbs and cannibalism, would (in the same way that a Varga girl shows a lot less than an explicit centerfold). But the appeal here is still the lure of the forbidden. This exhibit is necessary. Noir and westerns and detective fiction have all been accorded the respect of being taken seriously. Pulp art has not. The Brooklyn Museum exhibit of selections from Lesser's collection feels like a step on the road to giving these artists their due.

It's inevitable that the paintings will still strike some people as distasteful, or that their exhibition at a serious museum will be seen as a further eroding of the boundaries between high and low art. But one of the functions of museums should be to give the public a glimpse into its own culture. Apart from that, there is the sheer fact that these paintings are ravishingly beautiful. To respond to them, you have to have a taste for the unsubtle, you have to be willing to be seduced by the brightness of color and the dramatic impact of the nasty scenarios they represent.

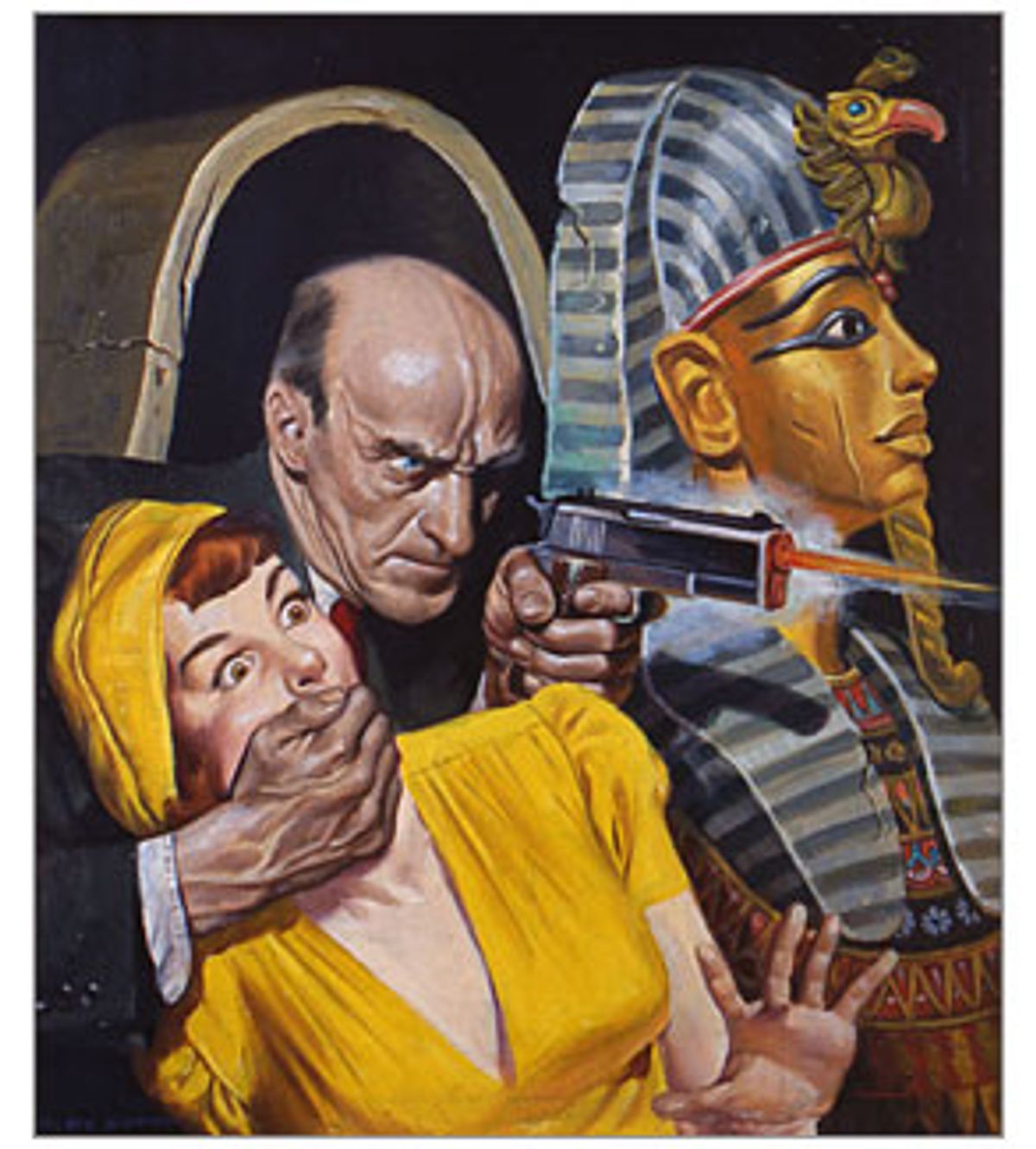

I don't want to put pulp art on a par with the masters. But purely in terms of subject matter, and leaving questions of technique aside, the reasons not to make the comparison become trickier. There is no good reason why anyone should recoil from Norman Saunders' canvas (for "Ten Story Detective") of a woman being kidnapped at gunpoint while a newsreel photographer swings his camera at the thugs' heads, yet blithely accept "The Rape of the Sabine Women" or the pain and suffering that is rendered with an undeniable sexual arousal in the work of Caravaggio. You could argue that our refusal to "see" or even acknowledge the violence in certified great art represents more of a coarsening of the senses that pulp art has been responsible for. (One of the strongest parts of Camille Paglia's "Sexual Personae" was her argument that we have denied the sheer violence and pornography of great art -- particularly her reading of Donatello's "David" as a chickenhawk hustler, which seems obvious just by looking at it.)

Lesser has preserved and presented these canvasses in a way that makes the colors pop out. They are often accompanied by a copy of the magazine on which the illustration appeared, allowing us to see a faded print against the vibrant original, and displayed against colored satin that corresponds to the primary colors of the painting. Color itself might be the subject of H. Winfield Scott's "The Oklahoma Kid" (1938) in which the cowboy hero's face is obscured under the brim of his ten-gallon hat and the emphasis is on his canary yellow shirt and read neckerchief. Of course on a real cowboy, or even in a John Ford movie, this would look more Village People than Dodge City. Here it speaks to the pulp artists' preoccupation with fantasy -- and with aesthetics -- rather than verisimilitude.

Some, like Rafael de Soto's "The Bookie and the Blonde" (1940), look like a deliberate subversion of the Americana of Rockwell and commercial illustration. A cop eats his lunch at a roadside counter, framed in a box of sunlight, while out of his view a thug with a pair of handcuffs dangling from his wrist holds a gun on the waitress, forcing her to pour poison into the coffee she's about to serve the policeman. There's no getting around the fact that women in peril were one of the pulp's biggest selling points, and that often the women have had their clothes ripped to reveal the lingerie underneath. In H.J. Ward's "Two Hands to Choke" (1934), a redhead in shredded clothes digs her nails into the face of the brute trying to subdue her.

In the 1938 "Black Pool for Hell Maidens" -- you know it's good just from that title -- a women is chained in the foreground while an evil-looking dwarf advances on her, and in the background another lovely is lowered into a vat of some boiling liquid. Some of the pulp readership was bound to get off on these images of women in distress. But I'd argue that the real appeal for the largely male pulp audience came from the next frame they conjured up in their heads -- the one where the rescued female offers up the charms we've glimpsed to her gallant rescuer. That was the role that the pulp readers wanted to imagine themselves in, and it seems even more obvious in the paintings where no women are present, where just one lone, usually good-looking hero moves in to finish off the usually brutish (or even deformed) villain. De Soto's "Revolt of the Underworld" (1942), an illustration for "The Spider," shows the eponymous hero swinging down on a rope to crash his feet into the throat of a nearly skeletal baddie. A spider web fans out on the wall behind the Spider and the shadow of a wolf, its jaws bared as if moving in for the kill, is also visible.

The fantasy covers are not usually so explicitly violent, but they represent some of the wildest flights of pulp art imagination -- not just the futuristic "Metropolis" architecture and the robots and flying saucers, but the figures. In Virgil Finlay's "Burn, Witch, Burn!" (1942) a naked women, her body spangled in stars, rises above a scene of villagers who appear to be thrashing a burning field. Behind her, the face of a green demon floats in the sky. The realistic figures here are literally dwarfed by the comely apparition, and no matter what the story it was meant to illustrate holds, you can't imagine cheering for them over this floating goddess. One of my favorites, "Creep Shadow," also by Finlay and also from 1942, shows a nude Jean Harlow-like blonde reclining on the backs of some frog-like sea creatures bearing her up to the crest of a wave. It's art nouveau gone gaga, a mix of sexual enticement and the delicacy of the lines forming the pattern of the waves.

For sheer visual impact and pleasure, I don't know when I've enjoyed an exhibit as much as this one. The paintings may have no depth; they are made to yield up their pleasure at once. But it would be foolish to underestimate how deeply they reach into our brains and our libidos. They inspire a lustful greed in the viewer, a sheer appetite for adventure and flesh that's bracing precisely because it's the opposite of politeness and refinement and taste. Pulp art was an open secret, a brazen display of the appetites we didn't acknowledge there on the newsstands every month. They were also among the most vibrant and colorful and exciting works of American commercial illustration. They should be celebrated for that, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art exhibit should be appreciated for shunning the hypocrisy that has long characterized the way they are regarded. Our spiciest, most violent fantasies are up on the walls for all to see. It's as if long-buried American desires are finally declaring themselves and saying, "Look how beautiful."

Shares