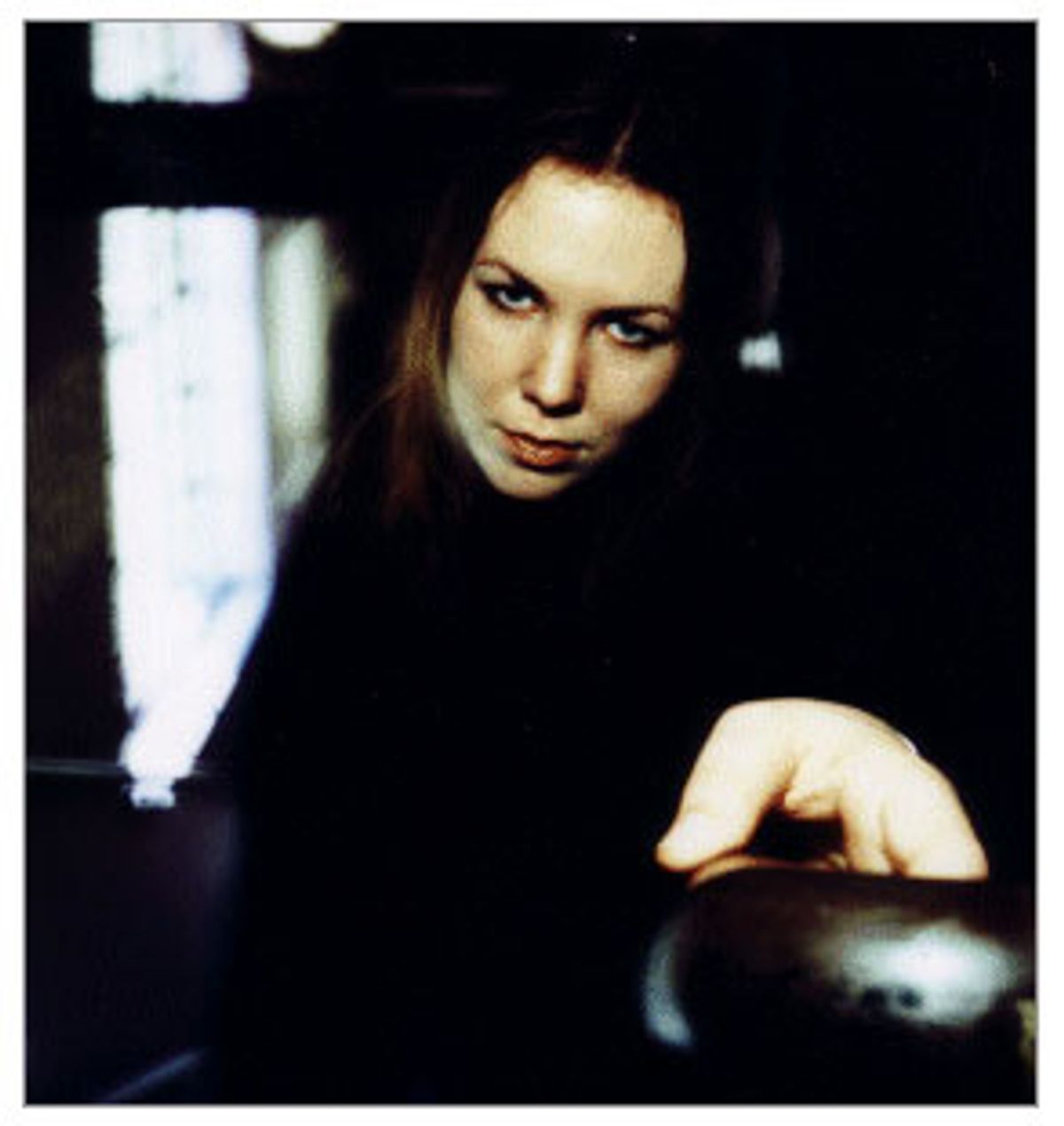

Thea Gilmore matters. Thea Gilmore is the real thing. Not just because this 23-year-old woman-child is a brilliant acerbic songwriter. Nor because she sings her verse with a voice you could imagine Emma Peel possessing if that black-leather secret agent could indeed sing. No. Thea Gilmore is important because her quirky five-CD oeuvre (her best and perhaps finest album, "Avalanche," released in mid-September) documents a prolific precocity we haven't witnessed since Elvis was a kid (I mean the British Elvis, of course).

Thea is also British, born in 1979. She began recording her own songs in 1995, when she was just 16. This teenager was no Britney, singing about puppy love and navel rings. Instead, she wrote lyrics like some delinquent Sylvia Plath: "I am like a bitch in heat"; "You fucked your way in, you can fuck your way out"; "You tattooed my image on the lips of all your friends/ As some tight cunt to fuck and leave and fuck again ..." Yet her sound wasn't punk. Gilmore's first records were produced with that guitar/keyboard ethereal Brian Eno-begat-Daniel Lanois-begat-Malcolm Burn high-tech whoosh sound (think Emmylou Harris' last few albums), the kid's lyrics sound elegantly dangerous, not juvenile -- the difference between a spotty girl with a Mohawk lugging an axe vs. a Hitchcock cool blonde in a evening gown hiding a razor between her legs.

By the time Gilmore hit 20, what had been juvenile and bombastic in her music matured into serious beauty. Terrible beauty. Her last three records -- recorded over a period of 18 months -- are just a notch below masterpieces. The three discs are "Rules for Jokers" (2002), the double CD "Songs From the Gutter" (2002; only available on the Internet) and the just-released "Avalanche." As we speak, she is recording a record of covers. She has just finished recording Neil Young's "The Old Laughing Lady" as she takes my phone call.

"On your new song 'Juliet,'" I say, "you sing, 'There's something so beautifully chic/ About burning out so young.' Can you tell me your life story before music?"

"I was born in Oxfordshire of hippie parents of Irish origin," she says. "It was a leafy upbringing. My mates were a few sheep and some cows that lived up the green. Horses were a massive part of my life. My mother does falconry by horseback. My father was a chiropractor who preferred treating horses to humans. I grew up on Bob Dylan records and ska. It was expected that I would be an accomplished rider, but I was excited by words at a young age. I shunned the equestrian life. I started writing songs and met my producer at 16. When you hit that age in England they make you go out and spend two weeks somewhere in what's called Work Experience. There was a recording studio near my house [Fairport Convention's Woodworm Studios]. I loved listening to music so I thought, 'Let's go hear how it is made.' I met this guy who walked in and we struck up a quiet, profound relationship about music."

That "guy," Nigel Stonier -- the girl's senior by at least a decade -- was a knockabout on the U.K. folk scene, writing songs for Fairport Convention and gigging with Lindisfarne. "I got to know Thea gradually through hanging out after sessions," he e-mails me. "She had this quiet intensity about her, and striking intelligence. I guess you kinda knew she was someone who'd be successful in whatever field she chose. She sent me a tape of five songs some time later. The first song was called 'Hydrogen,' and I'm not prone to dramatic pronouncement, but I can honestly say that 50 seconds in I knew I was hearing someone exceptional."

He produced Gilmore's first EP. Another elder named Sara Austin heard it and became her agent. Both have remained with their girl since. What a juicy story if these three had some kind of pseudo-Lolita ménage à trois going on! I only suggest it because it would fit the sexual dynamics of Gilmore's lyrics. What we know positively is that Nigel and Sara were junkies for Thea's talent. "I met Thea at the end of '96, when she was just turning 16," Austin tells me via e-mail. "The gig was a bit ropey but even then Thea had an awesome presence, and the songs were amazing."

Gilmore's "amazing" songs were hard for British critics to pin down from the jump. Since she was definitely not a neo-punk, she must be a "folk singer."

"Some people write me off as some waily folky woman," Thea says. "Other people think I'm rock. In terms of an image, if you want to be cold and corporate about it, it's hard to decide who my target market is. There isn't one. There is no box that I can be put in."

If Gilmore can get pissed at men in her songs, she gets even more enraged at the pop music industry. "There's a lunchtime radio show/ there's the shit that they play" goes one. "Tell me when did you get so safe?" goes another. "Oh those veiled love songs that you play/ Have you really got nothing better to say?" The centerpiece on "Avalanche" is "Mainstream," which is either a pastiche or an homage to Dylan's immortal line, "Johnny's in the basement mixin' up the medicine," only Thea attacks "angels in the abattoir junking up a good guitar," asking "Who's gonna train us, can you really blame us?/ If we grow up we're all going to be famous."

"Mainstream," the first single from "Avalanche," was released with a cover mocking Barbie. The Mattel Corporation saw red and lawyered up. Ian Brown, the self-proclaimed "pig farmer-turned-indie mogul" who runs Gilmore's small label, Hungry Dog Records, said in a press release: "I've had to retract all my existing artwork and delay the release of a new disk from the hottest thing to hit the English charts since I flicked my cigarette ash on them ... At a time when America is hurling fey singer songwriters at us at a dime-a-dozen, the glory of Gilmore is ever more telling."

Gilmore refuses to be marketed as product, of course. But as you listen over and over to "Avalanche," you hear flashes of femmed-up Tom Waits. Tin Pan Alley/the Brill Building. Lots and lots of Dylan. It is like seeing the influence of "The Seven Samurai," Buster Keaton, "Singin' in the Rain" and the entire history of Hong Kong cinema in a single shot of "The Matrix." Welcome to the post-influence era.

"Post-influence era?" Gilmore repeats with a chuckle. "Post-feminist. Post-post. There are so many new next big things. It's only the old next thing. There are so many bands that are really fantastic. You go, 'Yeah yeah yeah.' They're not doing anything different. They're trading on someone else's glories in a way." We speak of the dangers of high-tech production. "You can kind of lose things in the wash," Thea says. "Daniel Lanois is almost like the next big Phil Spector -- a big wall-of-sound guy. I think there are people it works for. I think Emmylou Harris' 'Wrecking Ball' album was just extraordinary."

Because I am writing an introduction to Thea Gilmore, I have to tell you that after playing "Avalanche" along with last year's "Rules for Jokers" nonstop for several months, I can't tell which one I love the most. "Rules'" production is more delicate, and in a way more masterful. In a song called "Keep Up" (about hanging out a window over a motorway) the voices of a background choir are compressed in such a way that they sound like a squeeze box made of crucified vocal cords. "Rules" also mocks high-tech production by including a goofy musical saw on many of the cuts, as if the record was the soundtrack to a cheesy 1950s drive-in ghost movie.

Gilmore's ghostplay is more overt on the album's centerpiece, "Holding Your Hand," when she promises over and over, "I'm gonna haunt you. I'm gonna haunt you. I'm gonna haunt you." The song is as high a work of art as Henry James' entire manuscript of "Turn of the Screw."

No examination of Thea Gilmore will be complete without discussing the CD that Thea released between "Rules for Jokers" and "Avalanche." "Songs From the Gutter" is a wonderful everything-but-the-kitchen-sink record, a bit like an unplanned pregnancy. It just happened. Gilmore and her band lucked into two days of free studio time, and she wrote and recorded seven songs on the spot.

"We were recording Dylan's 'Saint Augustine' for a Dylan tribute disc," she says. "I wasn't supposed to be recording an album. The 'Augustine' track went down really quickly, so everyone went out to the pub while I started writing some lyrics down. When the band came back, I asked them to play what I'd written. It was recorded in two days. We didn't intend it to come out until the point where it was sitting on the table in front of us and we said, 'What are we going to do with this?'" The second disk of "Songs" is a collection of a dozen B-sides going all the way back to Gilmore's teenage days. The album is a monument to the gods of prolificacy.

"I'm prolific and lucky," she remarks. "If there was an act out there that was writing songs at the rate that I am, they wouldn't be allowed to release them because their record company wouldn't be open to the fact that someone would want to release more than an album every three years. I can make as many records as I want." She pauses. "If I wanted to make five a year they might sort of object. They're fantastic. They're one bloke, actually, who has a heart of gold." (That would be Ian Brown, the former pig farmer.)

As for Gilmore's first two records, the first, "Burning Dorothy" (1998), is the lost disk. Her second, "Lipstick Conspiracy" (2002), is a sophomore effort and sounds like it. Start with either "Rules for Jokers" or "Avalanche." You won't be disappointed. Then order "Songs From the Gutter." I must warn you that when you first listen to this woman-child you will be struck by her caustic lyrics (think of her as the British Elvis' kid sister). She is the cynic who thinks Bogart and Bacall mythology is bullshit: "All those movie kisses just last too long yeah ..." She's a smirking siren in all her publicity photos. Yet, as you get familiar with her music, it is Gilmore's melodic songs that begin to dominate each CD. I have walked the streets of New York for blocks, playing a particularly melodious cut from either CD over and over on my Walkman. "Hey yeah I'm going home/ With the pirate moon."

"And oh my darling, oh my darling, oh my darling Benzedrine ... "

"There is cash on the table, here's a tapestry alphabet/ There's the moon and the tide and all the songs not written yet ... "

"I think the second half of 'Avalanche' is sweet," I tell Thea Gilmore.

"You think it's sweet?" she says, sounding incredulous.

"Yeah. The lyrics are kind of sweet. And so is your voice."

"Wow," She gasps and pauses. "I've never heard that one before." Pause. "I think I'm pleased with 'sweet.'"

Shares