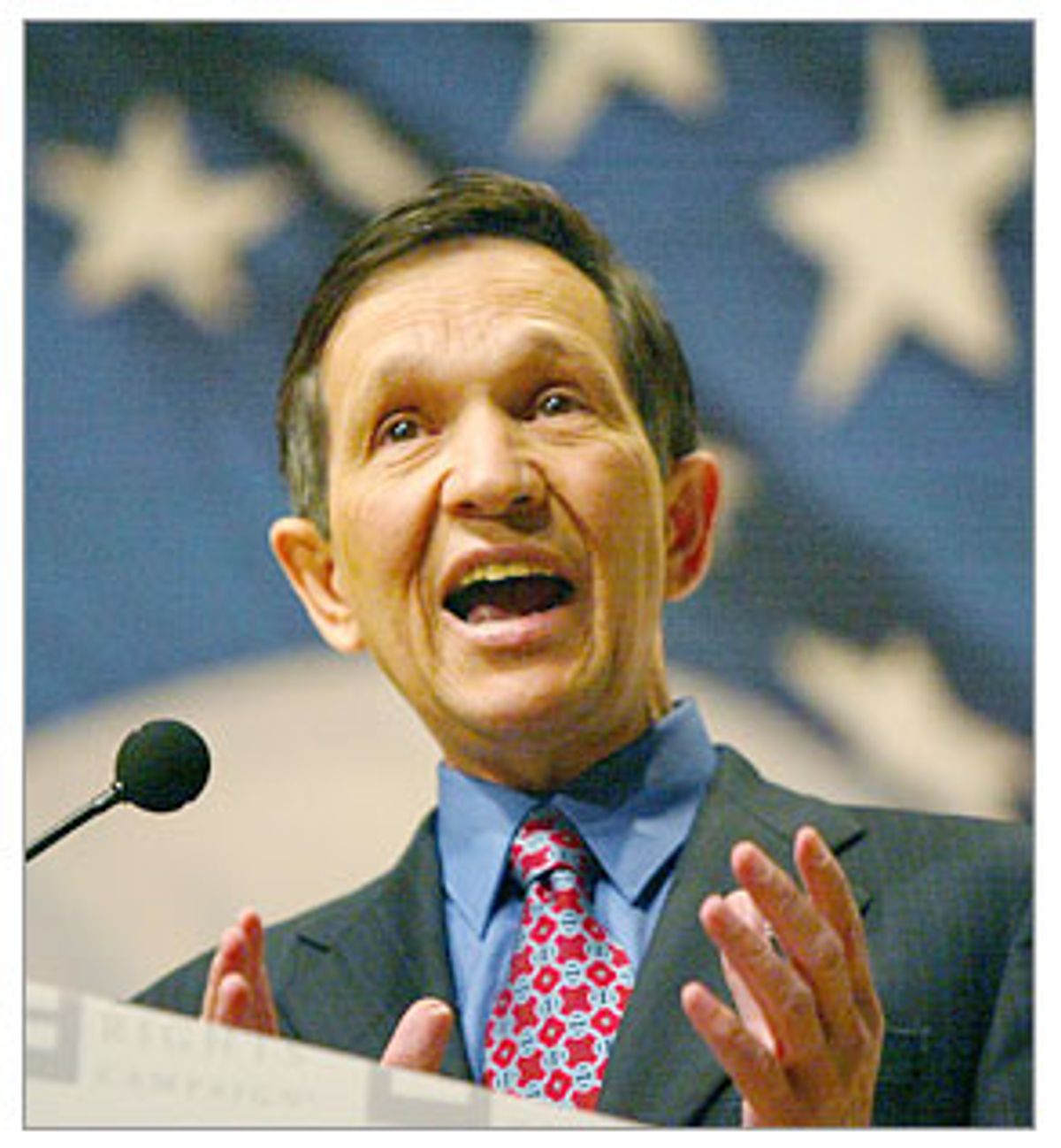

Rep. Dennis Kucinich caught presidential fever about 20 months ago. He had quickly written an impassioned speech, "A Prayer for America," about the evils of the Bush administration and his own hopes for the nation, which he gave to a conference of the Southern California Americans for Democratic Action. Without his knowledge, ADA leader Lila Garrett began circulating the speech on the Internet. Within weeks Kucinich received more than 25,000 enthusiastic e-mails. Last February, precisely a year and many speeches later, he initiated his presidential campaign at a labor union conference in Iowa, promising to deliver "a government you can call your own, a people's government, a workers' White House."

This week, with more attention to his Cleveland roots in a poor, transient, blue-collar family, he gave speeches relaunching his campaign with an equally undiluted progressive message as he flew around the country.

But if Kucinich initially felt the draft of political movement winds, those gusts haven't turned into a hurricane. Often dead-last among the nine contenders in national polls, such as a Washington Post/ABC poll released this week, Kucinich also has not yet succeeded in recruiting the support of many activists who agree with him on issues. He was an early opponent of war against Iraq and played the lead role in organizing 126 House members to vote against authorizing Bush to wage war. But Gov. Howard Dean and even Gen. Wesley Clark, both of whom have been somewhat less consistent war critics, have mainly benefited from Democratic antiwar sentiment. It has also been Dean, not Kucinich, despite Kucinich's closer ties to progressive movements, who has sparked a popular uprising so far with his campaign.

"It's fair to say progressives haven't consolidated around Dennis," acknowledged Kucinich campaign consultant Steve Cobble, who argued that the party's fractious left has rarely consolidated around any candidate, especially this early. Judged on the issues alone, Kucinich can convincingly lay claim to being the most authentic progressive standard-bearer in the race. Besides his hallmark opposition to the war, the PATRIOT Act and continued U.S. presence and military spending in Iraq, Kucinich has argued for single-payer universal health insurance (an expanded "Medicare for all"), vowed to withdraw from NAFTA and the World Trade Organization, pledged to cut military spending to fund education (starting with universal pre-kindergarten classes), and proposed rebuilding the manufacturing sector and using government research to create new high-tech industries. He promises to promote labor unions, break up corporate monopolies, fight privatization of government, and stimulate the economy with new public investment in roads, bridges and new energy systems.

But the liberal wing of the party wants something more, or at least different. "Dennis is a working-class hero," one labor leader said as he left a meeting to endorse Rep. Dick Gephardt. "I'm a huge Dennis Kucinich fan, but Dennis is an issues candidate." And this year a yearning for pragmatism dominates even among the more ideological activists -- even when what passes for hard-headed realism is often a finger-in-the-wind hunch about a candidate's so-called electability.

Kucinich's gut working-class sympathies and resistance to corporate power have brought him both political success and ruin. As a young mayor of Cleveland in the late 1970s he fought against the local banks and corporate elite that tried to force him to sell the city's municipal electrical system. The city was plunged into bankruptcy when Kucinich refused, which precipitated his defeat in the next election. After spending years in the political wilderness, Kucinich was eventually lauded as a hometown hero for saving Muny Light. He then upset Republican incumbents in "Reagan Democrat" districts on his way to a comeback in politics. Now in Congress he is the leader of the Progressive Caucus, and back home a leader in community and labor battles, such as saving both a local hospital and a steel mill from closing.

Yet Kucinich's low poll numbers reflect misgivings about the candidate and his political style, his failures to match Dean's grass-roots organizing, and a desperate desire among progressives to pick someone who seems likely to beat Bush. He seems trapped in the gap between ideological enthusiasm and political realism. He gets warm responses at diverse gatherings, from labor union conferences to meetings of yoga enthusiasts, vegans, animal rights activists and various New Age believers. When 2,000 sophisticated Democratic activists gathered last June for the progressive Campaign for America's Future's "Take Back America" conference, Kucinich "got by far the best response of anyone," said co-director Roger Hickey. "He was practically carried out of the hall on people's shoulders. If the people in that room voted their heart, most of them would be with Dennis. On the other hand, very few in that room saw him as a realistic nominee."

That's a recurring theme. "You get a lot of this, 'If I thought he could win, I'd vote for him,'" said Iowa Federation of Labor president Mark Smith. "I say if enough of you who think that way voted for him, he could win, but there's no traction in the polls. No traction. That's the brutal truth." Jeff Blum, executive director of U.S. Action, a national coalition of community and statewide citizen groups, said, "It's a fairly simple calculation people are making, that George Bush and his administration are so destructive to what this country is built on, back to the New Deal and the Progressive movement, that people are ranking winnability higher than they would have otherwise."

Kucinich, whose campaign won praise from Ralph Nader, has attracted Green Party leaders, some of whom have registered as Democrats to vote for him. "I love Dennis," said Medea Benjamin, founding director of Global Exchange, a San Francisco antiwar, anti-globalization group, and Green candidate in California for Senate in 2000. "He's so genuine, I wonder how he survives in Congress. He's one of the few people in Congress who understands, appreciates and works with activists ... But then it hits the reality. Dean has much more momentum. For some strange reason, he's been labeled 'electable' and Kucinich is labeled not electable, and these things have become almost self-fulfilling prophecy. Word gets out that Dennis' ears are too big or clothes don't fit, and people say I better put my bet on a winner and defect to the Dean campaign."

Soren Ambrose, policy analyst at 50 Years Is Enough, a Washington group critical of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, urged Kucinich to run last January to give voice to antiwar sentiments. "It was not that I perceived Kucinich would be president in a year and a half, but that we needed to change the center of political debate in the country," Ambrose said. But many antiwar and global justice movement activists who might seem likely ground troops for Kucinich's campaign are not interested in electoral politics, Ambrose noted.

"I am a supporter," he said. "If I could get bumper stickers, they'd be on my car. But right now as a national candidate for national office he has yet to find the right combination of message and style to make it stick." He needs to be "less shrill," Ambrose said, echoing a common observation that Kucinich often gets overly excited -- as if he's "on speed," some say (the clean-living Democrat is not) -- and combative when speaking, falling short of people's presidential expectations of authoritative demeanor and personal gravitas.

"Rather than coming across as a statesman for the progressive movement, he has come across more as a critic," argues TransAfrica Forum president Bill Fletcher, who adds that the campaign has also seemed "relatively weak on racial justice."

Kucinich clearly is not a cool, Clintonesque political figure. His speeches, all of which he writes, are artful throwbacks to a grand age of political oratory that inspire some but seem overwrought to others. He's a pre-ironic figure who takes both ideas and people seriously. While he has a sense of humor and playfulness (which can veer off into the unexpected as he breaks into a chorus of "Sixteen Tons" in the middle of a union speech), he rarely matches the quick wit that Sharpton demonstrates. Given their devotion to ideas, it clearly pains many progressives to discount Kucinich's campaign for personal qualities, but privately many comment that he doesn't look or sound presidential enough. "Maybe it's a question of charisma rather than substance," one activist said. "I wouldn't want to be quoted that Dennis is not the ideal national candidate, but I wouldn't deny it."

Then there's Kucinich's flirtations with New Age gurus and some policy proposals, like a Department of Peace, that strike many hardcore political types as intolerably flaky. "It pains me to say it, but Dennis needs to reach beyond the converted," Ambrose said. "He sounds a little out there and doesn't realize he's out there ... The Department of Peace idea I find the kind of thing guaranteed to keep you marginalized." One liberal union strategist argued that Kucinich's strong positions -- from single-payer health insurance to canceling NAFTA -- make him seem "unrealistic" and hard to take seriously. "I think that the Democratic left is a lot broader than Dennis Kucinich's left," she said.

But Kucinich campaign advisor Jeff Cohen, founder of FAIR (Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting) and a TV producer/commentator, insists that many supporters of Dean, Dick Gephardt, John Kerry and others prefer Kucinich but have doubts about his campaign. "If all of these people who are saying Kucinich is best, I like him on the issues, but -- fill in the blank -- if they quit letting the media impose assumptions that might not be true and went out and worked for Kucinich, you'd have a social movement on your hands." Cohen argues that the media, with a bias favoring free-trade policies and a lack of sympathy for the labor and peace movements with which Kucinich identifies, have not taken Kucinich seriously.

Campaign strategists see Kucinich trapped in a vicious and reinforcing circle of limited coverage, low name recognition, difficulty raising money, and low poll numbers. "If we don't raise money, we don't get press," Cobble said. "The press starts with the presumption that the liberal candidate won't win." But they rightly see the field as extremely unsettled, with no clear leader, and they claim that there are signs that Kucinich could break out. Fundraising was up for the quarter (though Kucinich's $1.65 million pales in comparison to Dean's $14.8 million), and the relaunch drew some good crowds, including 2,000 at a rally in Minneapolis.

Though he gets little press coverage, Kucinich arguably has pushed the rest of the Democratic field to be more critical of the war in Iraq and more supportive of fair trade rules. After Kucinich came out strongly against Bush's request for $87 billion more for the occupation and reconstruction in Iraq, both Kerry and John Edwards also shifted into the opposition camp. For some supporters, it's worth having Kucinich in the race simply to set a higher standard for what counts as progressive. "It's real important for Dennis to be in the race because of what he does to the other candidates," argues Iowa Public Policy project director David Osterberg. "Somebody needs to say that's where we ought to be, even if it takes a couple of elections to get there."

Kucinich also is developing a growing band of volunteers, but they're not always the typical enthusiastic college student or recent graduate. For example, Sue West, a 52-year-old United Auto Workers member from a factory in Rockford, Ill., and Margie Jessup, a 64-year-old computer programmer from Milton, Wis., devoted their summer vacation working together in Iowa for Kucinich. West liked Kucinich's antiwar stance, but she was also impressed when he joined her and fellow workers on their picket line last summer after their employer locked them out in a contract dispute. "I don't think there's one issue I don't agree with him on," West said. "I know he has a chance to win against Bush. He's so different. How can these other candidates win against Bush when they voted with him half the time?"

Back home in Cleveland, where he announced his candidacy to a city council room full of appreciative supporters, Kucinich seems salt of the earth, not flake of the month. "We love Dennis," said Cleveland Federation of Labor president John Ryan, who has worked closely with Kucinich for many years and sees his compassion, optimism and dogged determination as rooted in his hardscrabble family origins. "He calls me all the time with advice, suggestions, talking about how we should be involved in this or that issue. He is a wonderful set of eyes for working people. I can't say enough about him." He dismisses the idea that Kucinich is any less electable than the other candidates. "If anyone can end up being a contender in three or four months," Ryan said, "it's this guy," who can organize grass-roots efforts on the cheap and, with expectations so low, get a boost from even a middling early performance.

Kucinich argues that he can best beat Bush because he strikes the greatest contrast. But it's difficult for a progressive presidential candidate to go beyond ground prepared by popular political movements. The increasingly robust labor, global justice and antiwar movements have helped to make it politically popular, even necessary, for Democrats to be more supportive of unions, critical of free-trade agreements, and skeptical about the war than the centrists of the Democratic Leadership Council might like. Even if Kucinich were a stylistically stronger messenger with a better-organized and richer campaign, there are limits to how much a presidential candidate can reshape public opinion without popular movements having first laid the groundwork.

Shares