In François Dupeyron's cinematic confection "Monsieur Ibrahim and the Flowers of the Koran," Omar Sharif plays an old Muslim shopkeeper in 1960s Paris who dispenses sweet nuggets of wisdom to a young Jewish boy slightly lonelier and much, much sadder than he. (The film, in French with English subtitles, is now playing in New York and Los Angeles and thus will be eligible for the 2003 Oscars; a modest national rollout is due next month.)

"Smiling is what makes you happy," Sharif's M. Ibrahim tells young Momo, tenderly played by Pierre Boulanger, who drinks in his advice like nectar. "Try it, you'll see."

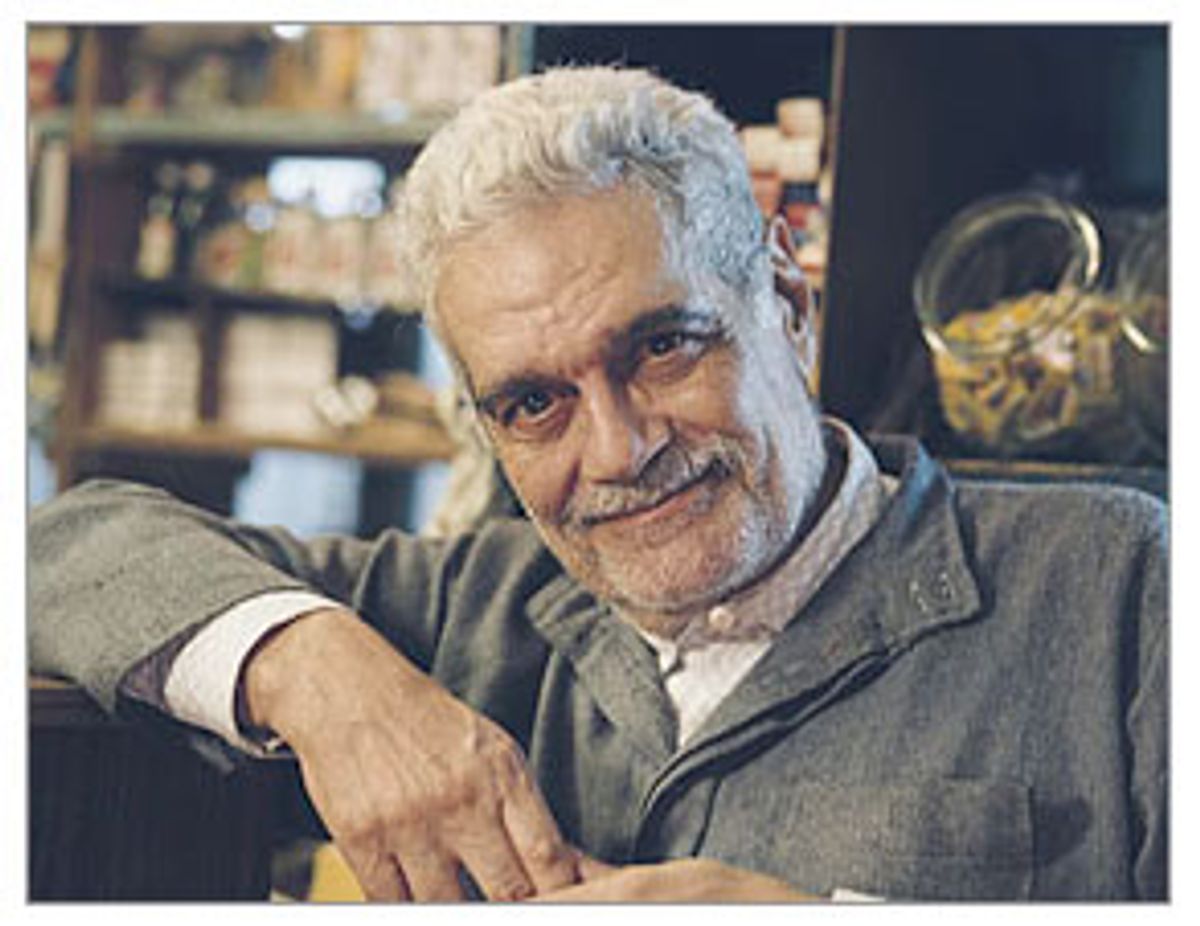

Sharif himself takes a similar don't-worry-be-happy view of life. Now 71, the roguishly handsome Egyptian actor, who dominated the box office in the early 1960s with hits like "Lawrence of Arabia," "Doctor Zhivago" and "Funny Girl," is looking back on a life lived passionately -- drinking good wines, dining on rich foods, romancing beautiful women, traveling the world, gambling much of his money away in casinos, competing at bridge and even getting into the occasional headline-making scuffle.

"I cannot stand the idea of having money in the bank and not spending it," he says. "It tempts me ... makes me want to do something exciting, rich."

Recently Sharif, who now lives in Paris, decided to renounce all passions in order to spend time with his family. He also decided to take a break from making bad films -- "25 years of rubbish," he says, "not one decent film" -- in order to wait for a role he could really feel proud of. When "Monsieur Ibrahim" came along with its message of religious tolerance and unlikely brotherhood, he knew he'd found just the role to sink his trademark gap-teeth into.

Grayer and growlier than he was in his heartthrob heyday, but no less charming, elegant and charismatic, Sharif met with Salon over coffee at a New York hotel one recent afternoon. (He does not do mornings, he says: "When there's no more light out, I'm happy") He looked deep into our eyes and told us a few of the things he's learned over the years.

"Monsieur Ibrahim" is your first movie in four years. Why this movie now?

There's too much violence around and this is a small but tender and gentle movie, and I really loved making it. I made it for my soul -- I didn't expect it to come to America. I thought it might stay two weeks in a cinema in Paris and that's it. But I liked the film and also I hadn't made a statement yet about the Middle East situation, and I felt I should because I am a loved person in the Middle East. I wanted to give my opinion -- that we can live together, we can love each other, it is not impossible. Stop killing each other. Sit and talk and be together. Making this movie might not change anything, but at least I know I said what I had on my mind.

So you felt like the film carried a message you'd been longing to convey?

Yes, but it's a fable. It's not reality, although it's based on the author's life. When I was thinking about my character, I wondered, how come this guy has had this grocery for maybe 40, 50 years and when the other customers come in, he never talks to them? He doesn't say, "How's your mother? How's your sister? How's your son?" He speaks only to this boy. When the boy isn't there, he doesn't exist. We never see him except when the boy walks in, as if his existence is tied to the boy's life. And he reads his mind. When the boy at the beginning is thinking, "Oh, he's only an Arab." Monsieur Ibrahim says, "I am not an Arab, Momo. I come from the Golden Crescent."

I wanted to make Ibrahim light and like a child. Obviously this man was lonely, but he was waiting for a child to play with, to be young with. When after a while, gradually, Monsieur Ibrahim and Momo become friends, they have fun together: they take the car and take driving lessons and go traveling. It's happy -- real happiness -- like two children having fun. That's what I wanted to put in this film.

Do you feel you succeeded in getting across what you wanted to?

Well, we needed to put one more little thing into the film. We needed one scene during the voyage where we are totally happy. Where the boy is laughing and is really having a good time, just laughing his head off, because he's very somber and life was so miserable. It needed just this one more little scene. I didn't notice it when I read it nor when I was shooting it, but when I saw it, I realized it needed this one scene.

At one point, your character does say, "I'm happy, Momo."

Yes, when I'm dying. It is the last lesson that I'm giving to the boy: How to die, that dying is not something terrible. "I am not dying," he says to Momo, because Momo is crying. "I'm just going to the immensity." It's something to smile about, not to be sad.

Did you bring anything from your own life to the role?

I don't know whether he brought it to me or I brought it to him, because we ended up being exactly the same. I mean, I have now the same opinions as M. Ibrahim. Something happened in that film that made me agree with everything he says.

You see, I have this relationship with my grandson. I have two grandchildren. One is 20 and he's Jewish, and one is 4 and he's Muslim. They're brothers and they love each other. My son married an Orthodox Polish Jewish woman, and then he married a Catholic who didn't have children and now he's married to a Muslim girl and he's got this little boy. And I play with my grandchildren like mad, like a child. I risk breaking my back sometimes -- I roll on the ground. So maybe this is it, I love children, love to play with them, and M. Ibrahim obviously was waiting to have a child.

And you were waiting for this film. You were retired for a while, weren't you?

I had decided not to work anymore just to earn money to eat. I decided that I would not work if I didn't find something good. I decided to stop unless something good came along, something that I liked, that I wanted to make an effort for, and do it with pleasure, with passion.

What was the last worthwhile film you made?

It was years ago. See, what happened was after I made my three famous films -- "Lawrence" and "Zhivago" and "Funny Girl" -- I made good choices. I had five films with great directors; they were flops. And after five flops in the movie business, it's very difficult to find parts, especially since I'm a foreigner. I'm not a Spanish foreigner and I'm not an Italian foreigner and I'm not a French foreigner. I'm a foreigner -- to everyplace. When I was a box-office draw, they used to cast me as anything -- I played German officers, I played Russian poets, I played a New York Jew. As long as you're a box-office draw, you can play anything. But once you aren't so big at the box office, they're not so interested, or they only ask for you if they need an Arab. If they need an Arab, they call me, but Arab parts are often in bad films and caricatures -- so uninteresting. And I had to work to support my family. I was exiled, myself, from Egypt, because I was working only with Jewish people. And I was worried that they would take it out on my parents, so I took everybody out -- my father, my mother, my sister, my son, my nephews, my nieces -- and I resettled them. So I had a big family to look after and I had a secretary and a housekeeper and cook -- all the big expenses to keep a big family like that.

That's a big responsibility.

Well, that's normal. Everyone has responsibilities.

Not everyone has to take care of their entire extended family.

Yes, but I was making a lot of money, so it wasn't a problem as long as I kept working.

So you were working in order to support them and you no longer have to do that?

I have enough money to live for three or four years without working, so I will do that if nothing good comes along. And then, if I am still alive, I will have to do something, I don't know what, to make some money. And I hope that my son -- he's 46 and I set him up with a beautiful shmata business, you know; he makes shirts and clothes for men -- and I hope that he will make some money so that he can support me when I'm old.

That's right. At 46, the parent-child balance shifts a little.

But he's a lousy businessman. He's as bad at business as I am -- except he thinks he's good. I'm bad, but I know I'm bad. He's bad and he thinks he's great.

That sounds dangerous. Let's talk about bridge for a little bit.

I've given that up.

Why?

I don't want to be a slave to any passion any longer. I gave up all the things that I was passionate about, so that I can be -- if a good film comes, I can be passionate now about it. I am now passionate about being with my family, because I haven't spent enough time with them. I live in the moment now. I don't want to think of the past and I don't want to think of the future. I want to concentrate on every instance of my life because that's what's important. When I talk to you, I don't think of anything else except our conversation, nothing that came before and nothing that comes afterwards.

How long did you play bridge?

I started when I was 21 and then bridge became very important to me, especially in this period when I was making these bad films. I became a great bridge player and therefore I kept some self-esteem -- that I was good at something that I was doing, that I was successful at something. And I went to casinos and I gambled and I led a very crazy life so that I would not think about the lousy films I was making and wouldn't be humiliated by it.

So now you're not playing at all?

I play for charities. I have some charities that I work for, so when I want to raise money sometimes I organize a bridge tournament and auction off professional bridge players and myself. People pay money to play with me and it goes to support charity.

And you wrote a bridge column for a while, right?

Yes, but that's not me. It was by friends of mine who wanted to make some money. They asked me if they could borrow my name so that they could be published and I said OK. I never got money for it. It was one of the largest syndicated columns in the world. It ran in hundreds of daily newspapers, but I don't know how many papers ran it in the States, because I never got money for it.

It was written under your byline, but you didn't make a cent? Your friends made all the money?

Yeah, they made some money. Why not? I want to earn my money from acting. I don't want to earn money any other way. It doesn't interest me. I don't invest, for instance, in the stock market or in anything. I don't have a house. I earn money, I spend it.

What do you spend it on?

On crazy things. I have to spend it. On dinners. I buy racehorses. If I can't find any other way I go and gamble it away or something. I cannot stand the idea of having money in the bank and not spending it. It tempts me. The fact that I have money makes me want to do something exciting, rich. You know, to have the best wine and the best food. But if I'm poor, when I don't have money, I don't mind having a sandwich and a beer.

It sounds like you've gone through a tremendous amount of changes in your lifetime.

You have to. People don't stay always the same. No one is always something. You can't be the same at 20 as at 70. It's impossible. It's stupid. If you don't change, then you're very unhappy. See, the great secret of happiness is something very simple: to be satisfied with every age you are. Not to be 20 and want to be 30. Not to be 50 and want to be 40. And not to be 70 and want to be 16. Because all these ages have their own pleasures. I have my pleasures. If I was not my age, I would not have two grandchildren whom I can love and talk to and play with and be proud of. See? All these things are part of pleasures that I couldn't have had before when I was younger. And if I had not made 25 lousy films, I wouldn't be happy to make one little film that I like.

That's a very M. Ibrahim-like thing to say. What's your next good film going to be?

I made a film for Walt Disney ["Hidalgo," with Viggo Mortensen] which I had a very nice part in, long dialogue scenes. I like to work out how I'm going to speak them and what the rhythm should be and how quick it should go and how slowly. You know, it's fun. Acting is fun. The film doesn't have to terrific, but at least my part has to be interesting, or I have to be interested in playing my part. That's all I need. I can't guarantee that every time I'm going to be able to make a good film.

Do you go through a specific process in order to inhabit a role?

Once I decide to play something, I think about it all the time, even while I'm eating. I try to get the visual image of the character, first of all, a physical sense of him. You know, for instance, with this film, I realized my shoulders are too broad to play an old man, and so I tried first of all to keep them in, like this, and also, I put on some weight down here [stomach] so that I would be more triangular, like a man who sits on a stool all day. So, you've got to work out the physical thing. Once you've got the physical down, then you start behaving like the character. It inspires you to walk in a certain way. And then come to the part where you have the lines and you imagine what kind of person you are: Are you happy or unhappy, young or old? It's a technical thing. It's for acting schools. It's not for you.

Do you still get recognized a lot and treated like a heartthrob wherever you go?

Not like a heartthrob. I'm too old to be a heartthrob, but yes, I get recognized. The only difference between now and before is that a lot of girls come to ask me for autographs and say, "My mother loved you," "My grandmother loves you." But it moves me much more than if a girl asks me for herself. It moves me because mothers move me, grandmothers move me. When you say, "for my mother or my grandmother," it touches me profoundly, because people love their mothers and their grandmothers and they love the people that their mothers and their grandmothers love, so that by proxy, they love me.

How did you hold onto your sense of self through your years in Hollywood?

That is a matter of education, darling. You know, I never changed since I was 10. I am the same person. I never changed my personality in any way, nor what I think of myself. I never thought that I am a genius or that I was important just because I had success. It didn't go to my head in any way. But that is upbringing. I was lucky because in my time, parents didn't divorce. They stayed married all their lives, my parents. My mother was always there when I was eating and when I was doing my homework and she used to put me, when I made mistakes, on the sofa on my tummy and take her slipper off and gave me a little spanking. It didn't hurt so much. It's nice to know that someone is there, caring for you, wanting you to be good, wanting you to improve yourself, to be perfect. My mother helped me to be somebody. She had decided that I had to be somebody.

Were you able to be there in the same way for your son?

Well, you see, I divorced my wife when my son was 8 and a half. And my wife [Egyptian actress Faten Hamama], who was a wonderful woman, was very clever, and as I was leaving Egypt, and she was staying because she is a great actress, she said, "Take your son with you, because you'll be able to give him a better education in Europe and in America than I can give him in Egypt." She sacrificed that. So I lived with my son alone. That's why I never remarried and I never wanted a woman in the house. I never wanted him to have a stepmother like the one from "Cinderella." And of course, he missed the maternal affection. So my son, contrary to me, cannot live without a girl with him, because he didn't have his mother around too much.

Whereas I, who had a tremendously motherly mother, a real Jewish mother type who was always on top of me, am not in need so much. The women that I've liked in my life were never the type that were servile. I like a woman who works and then can come back and talk about what she did all day, what I did. I like independent women. I don't like these women who are always there, always cooking. I can't stand that.

The description you have of the contrast between you and your son is remarkably like the two characters in "Monsieur Ibrahim": Momo, who's desperate for parental love, and M. Ibrahim, who's very satisfied with his lot in life.

Yes. It is like that. And it's beautifully written. If you understood French, the language is beautiful. He's a great writer, that guy [screenwriter Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, who also wrote the book and play on which the film is based]. It was so moving to me, this whole relationship between this lonely, unhappy boy and this lonely old man.

How many languages do you speak?

I speak five languages, but I don't have a mother tongue. I have an accent in all five.

Even in Arabic?

I have an accent. When I used to make Egyptian films, the critics used to say, "He's got a little bit of a foreign accent." But you know, the Egyptian women loved my accent. One of the things the women there loved me for was because I didn't speak the way other Egyptians spoke. I have a softer accent and a softer voice. So what was a defect became a positive quality for me.

You clearly work hard at your craft. Were you ever tempted just to coast on your good looks?

No, I have never done that. In fact, I never look in a mirror, unless I have to shave or something. On sets, I never have the makeup person come and hold the mirror. I never look. I am not interested in my looks. I had good looks, I knew it. It's not that I didn't know it. I knew that when I was young I was very good-looking. There's no way of not knowing it. But that I consider a gift from God, a piece of luck. And I never really understood why -- I mean people who believe in God, believe in this -- why should some people be so favored in life and other people be so not favored? I mean, people who are born poor in Bangladesh or in Rwanda with no food and famines and floods and all sorts of bad things happening in their countries, or they're crippled or they're ugly.

And then you create someone who's handsome, and my parents were wealthy. I always thought it was so unfair because I was born in a country where you saw people who were poor, you saw them dying of hunger. That's why I almost didn't want my beauty, my good looks. I resented the fact that I was so lucky in the middle of unlucky people.

Shares