Computer graphics made Peter Jackson's "Lord of the Rings" trilogy possible, and for that we should always be grateful. Even a generation ago, no one would have tried to adapt J.R.R. Tolkien's fantasy epic as live-action cinema. (Someone might have given it a whirl in the 1920s, had the tale existed then, but that was another age and another kind of movie.) Without digital wizardry, we'd never have seen Jackson's fearsome Wargs and mighty Ents, the pits beneath Isengard where Saruman bred the Uruk-hai, the Ringwraiths on Weathertop, the mines of Moria, the white city of Minas Tirith or the terrible creature who guards the pass of Cirith Ungol -- none of it.

And we'd have been poorer for it. With "The Return of the King," Jackson, his remarkable cast and his enormous ensemble of collaborators have found victory at the end of their improbable quest. Like the indomitable hobbit heroes Frodo (Elijah Wood) and Sam (Sean Astin), who eventually find their way to the Cracks of Doom where Sauron, long eons ago, forged the Ring of Power (in deference to those of you who haven't read the books, I won't discuss what happens there), Jackson and company have accomplished the near-impossible. While remaining true to the spirit (if not the letter) of Tolkien's books, "The Lord of the Rings" is also a prodigiously exciting film entertainment, a redemption of the spirit of popular spectacle that has seemed so cheapened, corrupted and bastardized in recent years.

Packed with passion and heroism, the grimness of death and the hope of salvation, this final chapter flies past with the speed of Shadowfax, Gandalf the wizard's legendary white horse. None of us is ever again likely to encounter a 200-minute movie we are so reluctant to see come to an end. Expectations for "The Return of the King" are of course outlandish -- if it does not become the highest-grossing film in history and win the best-picture Oscar, it may be considered a disappointment -- but as unfair as they may be, I expect to see them fulfilled. Although I'll always have a soft spot for "The Fellowship of the Ring," which made us all believe that this implausible endeavor might actually work, this one is Jackson's crowning achievement. It marks "The Lord of the Rings," without any serious question, as the greatest long-form work in the history of mainstream cinema. (Do I hear any other nominees?)

By their very nature, endings are occasions for sorrow, and Jackson honors the elegiac spirit of Tolkien's epic by infusing the triumphant tale of "The Return of the King" with a deepening sense of sadness and loss. As the author's devoted fans know already, the end of this saga marks the passing of much of Middle-earth's beauty (symbolized by the doomed magic of the Elves) and the beginning of the Age of Men -- in other words, the inauguration of our world, with all its grime and mess and morality in murky shades of gray.

As we walked out of the theater, my viewing companion expressed a more direct sadness: There will be no new "Lord of the Rings" film next Christmas! (There are rumors that Jackson may make a film of "The Hobbit," Tolkien's prequel, but I suspect that may be the denial that marks the first stage in the Kübler-Ross process of grieving.) Yes, these movies, like Tolkien's books, will be with us forever -- and the DVD versions may last forever -- but the vast popular audience that has embraced this amazing series will now share that Baggins-like bittersweet sensation of travelers who have ventured to the edge of the world and find themselves with no new lands to conquer.

More than Tolkien's books, Jackson's movies are first and foremost grand entertainments; in his screenplays (co-written with Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens) the high-flown rhetoric and mythological heavy lifting have, thankfully, been kept to a minimum. But Jackson hasn't lost sight of the fact that the "Lord of the Rings" universe is not entirely imaginary, and that its realism -- its sense of distant but tangible connection to our own world -- is what lends it much of its power. So while this series would never have come to fruition without the magic of the digital age, that does not begin to account for how riveting -- how real -- Jackson's portrayal of Middle-earth is.

In fact, I'll go further than that: The special effects in these movies are something like the One Ring -- perhaps a necessary evil, but a great evil nonetheless, one that constantly threatens to undermine the creative spirit. Sure, some of the series' effects are absolutely essential: the thrilling battle scenes in "The Two Towers" and in this film, the marvelously pathetic creation that is Gollum, the ancient and horrible Shelob (literally, in Middle English, "female spider"), who brings Frodo and Sam to their darkest hour of the entire saga. The list could go on.

But, listen, as much as I love these movies, it's time to be honest. We're among friends here. We can admit that the cheeseball factor is set at least 10 percent too high.

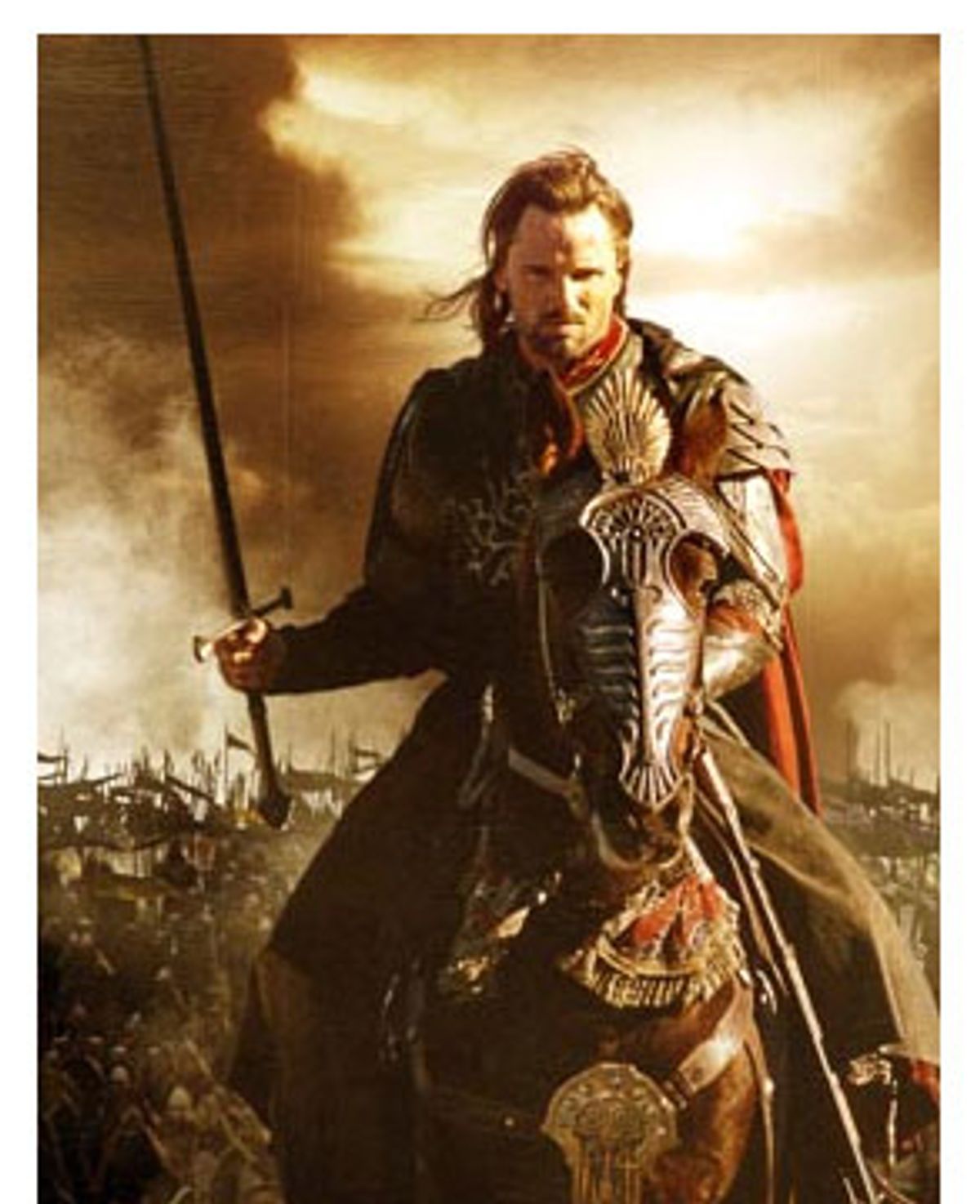

Didn't you actually feel a little let down by those ghostie Shroud of Turin night-vision Nazgûl in "The Fellowship of the Ring"? Or by their flying goofball dinos, straight out of Raquel Welch's 1966 "One Million Years B.C.," in "The Two Towers"? It's OK, I thought so. Well, wait till you get a load of the translucent army of spectral swordsmen conjured up by Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) in "The Return of the King." We're talking Pirates of the Caribbean here, folks, and I mean the Disneyland ride rather than the Johnny Depp movie. I kept waiting for them to dance a cheerful skeleton hornpipe, or play soccer with each other's heads.

Then there's that big-ass cartoon Eye, oscillating inside that tuning fork or radio antenna or whatever it is on top of the Dark Tower. No, I don't think it's crucial that Jackson stick to the books in every detail (in Tolkien, the evil Sauron actually has a blackened and disfigured physical form, although he never appears in person). And maybe there's an argument for taking Sauron's symbol, the Lidless Eye, and making it literal. But every time I see it -- and you see it a lot in "The Return of the King" -- I get bummed out. This wobbling, ectoplasmic searchlight-thingy is the Dark Lord himself, the embodiment of evil? OK, maybe it's scary at first, but the more you see it scouring the landscape and doing exaggerated double takes, the more it becomes, well, scary-cute, in a Tom-staring-down the-mouse-hole in-search-of-Jerry way. What's ol' Saur going to do with the Ring if he ever gets it back? Balance it on top of his googly, eyeball-jelly head? "Blass-st you, wretched halfling! I have no fingersss!"

But I love Jackson's "Rings" saga despite his propensity for whimsical animation whenever he tries to strike a chord of dread or menace. Above all else, I love it for its sense that these extraordinary adventures are happening to ordinary folks in real places, not in some airy-fairy, mystical-fantastical sphere. There's a remarkable scene about midway through "The Return of the King" when Gandalf (Ian McKellen) and the hobbit Pippin (Billy Boyd, one of the stars of this installment) stand at the walls of Minas Tirith, capital city of the land of Gondor, and look out at the landscape. In the middle distance, the ruined city of Osgiliath, overrun by Orcs, burns along the riverbank. Further off, behind the dark mountain range that marks the boundaries of Mordor, Mount Doom belches red into the sky.

It's a scene of thickening, oppressive tension -- a momentary calm before the devastating siege to come -- and it makes you see, in a way the books can never convey, the early-medieval closeness of this world. Travel happens only on foot or on horseback, and it's no more than a few days' ride from Minas Tirith to Sauron's Barad-Dûr. These are not the nation-states of the 20th century, flinging bombs and missiles and great seaborne armies at each other across vast geographical distances; these are the warring fiefdoms of premodern Europe, jammed together in a corner of the globe and massacring each other in hand-to-hand combat. (Of course, much of this awesome landscape is digitized, while some of it is the real New Zealand -- but I don't exactly know which is which and I don't want to.)

As we know from "The Two Towers," the fellowship appointed to carry the Ring into Mordor and cast it into the fire whence it came has split apart. The crosscutting between these two (and soon three and then arguably four) different story lines, which can sometimes feel like a narrative liability in the books, is tailor-made for the movie screen. Frodo and Sam, accompanied by the increasingly untrustworthy Gollum (the voice of Andy Serkis, attached to that amazingly creepy techno-creature), are struggling over the Mountains of Shadow, hopelessly alone, with almost no weapons and almost no food. Frodo is carrying the most important single artifact in the entire world, and the weight of his burden is making him look thinner, more haggard and more Gollum-like every day.

Pippin and Gandalf ride for Minas Tirith, rendered here as a pseudo-Italian hill town in white marble, where the steward of the city, Denethor (John Noble), devastated by the death of his son Boromir (in "Fellowship"), is facing an imminent Orc-invasion and radically losing his grip. In the horsey, rough-hewn realm of Rohan, whose early Anglo-Saxon design is one of this series' great visual triumphs, Aragorn -- the King of Gondor, coming to reclaim his throne -- along with Legolas (Orlando Bloom), Gimli (John Rhys-Davies) and Merry (Dominic Monaghan), must convince the reinvigorated King Théoden (Bernard Hill) to assemble his rustic crew of cavaliers and ride to Gondor's rescue before Sauron's forces can overrun Minas Tirith.

Beginning with the film's very first episode -- the story of two long-ago hobbits named Sméagol and Déagol, and the beautiful golden ring they find one day on a river bottom, glowing like a giant donut -- Jackson sustains a pulse-pounding pace and a mood of mounting eeriness. Frodo and Sam pass the Nazgûl dead city of Minas Morgul, which glows phosphorescent, like an especially evil version of the Mormon Temple. (Hold those cards and letters, LDS people; I don't actually think you're soul-destroying undead warlocks.) They head up the Winding Stair into the mountains, through a secret pass that Gollum is just a little too enthusiastic about. Meanwhile, the senile and demented Denethor sends his surviving son, Faramir (David Wenham), into battle against an overwhelming force of Orcs. In a scene of Orson Welles-like grandeur, Pippin sings for Denethor as the old man messily eats fruit -- and the young men he has dispatched ride to their deaths. In fairness, this expresses a contemporary antiwar sentiment unlike anything found in Tolkien -- but as pure cinema, it's the equal of any moment in this series.

As the forces of evil lay a terrible siege around Minas Tirith, as Frodo's burden becomes too much for him to bear, as the men of the Riddermark (and, yes, one woman) saddle up for war, so much is going on you can hardly follow it. There's the quiet, soulful way that Mortensen, as Aragorn, can anchor a scene while hardly saying anything. There's the supernatural beauty of Liv Tyler as Arwen, Evening Star of the Elves, who must decide whether to stay in Middle-earth and help her beloved Aragorn or sail to immortality with the rest of her race. There are Sam and Frodo, now just barely alive, struggling across the rock-strewn plains of Mordor in stolen armor like a pair of lost baby Orcs. (Do Orcs in fact have babies? If so, are they cute?)

Few film directors in any style, or at any point in the medium's history, have had Jackson's eye (aided immeasurably by cinematographer Andrew Lesnie) for the sweeping, Shakespearean gesture and his affinity for the fine details of an intimate composition. (I'm serious. D.W. Griffith? Welles? Kurosawa? Martin Scorsese? That's about it.) The two massive battle scenes in "The Return of the King," with their trolls, their giant elephants and their flaming-boar battering rams, may be the finest spectacles of their kind ever set on celluloid. But there are other things here you will remember just as long: The tender scene between Sam and Frodo when they become certain they will never see their beloved Shire again, the moment when Aragorn finally convinces Éowyn (Miranda Otto) that he doesn't love her and never will, the gradual realization of Elrond (Hugo Weaving) that he will lose his beloved daughter Arwen to a human.

Tolkien purists may be less happy with "The Return of the King" than with the other chapters of Jackson's trilogy. Several subplots have been dropped entirely, like the fate of Saruman and the miniwar that follows the hobbits' return to the Shire, and others, such as the romance between Éowyn and Faramir, have been whittled to almost nothing. In some alternate universe, Jackson could have made a 30-hour miniseries to make such people happy. In this universe, he has merely made the grandest and most delicate of pop spectacles, an epic that is heroic but almost never grandiose, a story of war that understands that within every great victory there lies a kind of defeat.

Shares