The year in sports was one of bad behavior, malfeasance, wrongdoing.

There were errors, screwups, bad calls and sour notes, same as always, and all that was mixed as usual with the uplift and glory that sports are so good at providing. In that way, 2003 wasn’t unique.

But there was also evil. There was behavior so foul that thinking sports fans had to ask themselves just what kind of enterprise it was they were supporting with their money, their time and their emotions. 2003 was an awful year to be a fan.

There’s lying, cheating, stealing and worse in all walks of life. In any culture, bad behavior is part of the story. But for the year in sports 2003, bad behavior was the story.

It started and ended innocently enough, with football officiating snafus, a terrible pass interference call that decided the national college championship game, an uncalled penalty that cost the New York Giants a chance at a win in the playoffs, a controversy that had a majority of fans, according to polls, grumbling about the choice of teams in the upcoming college title game. The stuff of barstool debate, no big deal.

But between those teacup tempests a scandal that began with murder swept over Baylor University, and before it was over the actions of basketball coach Dave Bliss were revealed to be so depraved as to make even the year’s unusually dense crop of college sports misbehavior seem quaintly innocuous. Bliss’ attempt to derail the investigation into the killing of Patrick Dennehy, his own player, in order to protect his dirty program made the many on-field controversies in 2003 seem downright folksy in comparison. (Carlton Dotson, Dennehy’s former teammate, has pleaded not guilty to the murder and awaits trial in Waco, Texas.)

Bliss resigned after an assistant coach taped him trying to persuade Baylor assistants and players to lie and say Dennehy had been dealing drugs to pay for his tuition, an attempt to cover up illegal payments made to Dennehy in lieu of a scholarship. The subsequent investigation turned up a host of NCAA violations at Baylor, a perennial basketball loser. Given Bliss’ willingness to defame the memory of his own player to protect a losing program, it’s almost impossible to imagine the lengths to which he might have gone to protect a winner.

The shameful episode at Baylor dwarfed the pedestrian amorality of the rest of the sports world, even in a year when the college ranks were defined by scandal:

While Clarett balanced on the very thin line that separates college and pro sports, two stories dominated the latter, especially in the second half of the year. Both were particularly depressing.

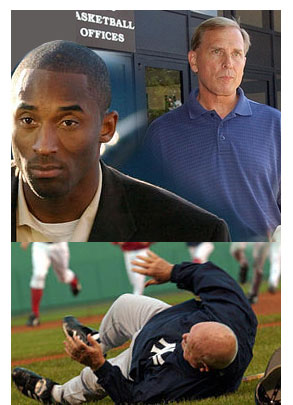

One of the sporting world’s most popular stars, Kobe Bryant, was accused of rape in Colorado. He denies it, saying the sex he had with a 19-year-old hotel employee was consensual. He ends the year shuttling between his job with the Lakers and court appearances in Eagle, Colo., where he faces trial next year. Even if he’s cleared of the rape charge, the facts that have already been established in the case — that the superstar cheated on his very young wife, the mother of his very young child; that even after seven years with the Lakers, he’s remained aloof and unable to be one of the guys; that he’s shown little apparent remorse for the way his legal troubles have affected the team, opening the season with a bizarre verbal attack on Shaquille O’Neal — have forever diminished his appeal.

And in a story with far broader consequences, a parade of superstars including Barry Bonds and Jason Giambi testified in front of a federal grand jury investigating the Bay Area Laboratory Cooperative (BALCO), a Burlingame, Calif., dietary supplement company suspected of providing the newly discovered designer steroid THG to athletes. Four Oakland Raiders and dozens of other high-profile athletes are reported to have tested positive for THG, which in October was declared an unapproved new drug by the Food and Drug Administration.

THG was uncovered by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, which polices drug use by Olympic athletes, after an anonymous track coach sent a used syringe to the agency, which reverse-engineered a test to reveal the previously unknown drug. The coach said the contents of the syringe came from BALCO, which BALCO owner Victor Conte denies.

The THG revelation roughly coincided with news that more than 5 percent of major league baseball players had tested positive for steroids in anonymous testing, which triggered a clause in the collective bargaining agreement: Players will be systematically tested for steroids beginning in 2004 and punished if they test positive. This was all in the same year that witnessed the ephedra-related death of Orioles pitcher Steve Bechler.

Though the 5-7 percent figure released by Major League Baseball was far lower than the level of steroid use alleged by Ken Caminiti, Jose Canseco and David Wells in recent years, it and the THG revelations confirmed many fans’ long-held suspicions that steroid use is a common, mostly undetected fact of life in professional and Olympic sports. Where once fans had to learn about split-finger pitches and zone defenses to stay current, now they must be experts in pharmacology, a class for which — much like salary “capology” — most never signed up.

But using illegal steroids isn’t the only way to cheat. Another beloved superstar disappointed his public this spring when Sammy Sosa’s bat shattered in a game, revealing an illegal cork filling. Sosa apologized, saying he’d grabbed a batting practice bat by mistake — an excuse few who have ever handled a bat for a living went on record as believing — served his suspension, and returned to have a fine, cork-free season. But the incident cast a shadow for many fans over Sosa’s prodigious home run output of the last six years, even though it’s doubtful that corking a bat actually increases a hitter’s power.

Bad behavior was so prevalent this year that it even carried over into the next life. The children of the baseball legend Ted Williams squabbled over the disposition of his remains, leading to the dismally comic image of the slugger’s disembodied head sitting on a shelf in a new-age cryonics facility in Arizona. The steady stream of late-night talk-show jokes about the situation disproved the old saw that dying is easy, comedy is hard.

A few of the cast of characters who found themselves in hot water in 2003 for offensive or inappropriate comments were shooting for comedy, but most were simply expressing themselves, which is all the more depressing.

Football players Jeremy Shockey and Garrison Hearst and executive Matt Millen made or shouted homophobic statements. Mike Tyson, who denies that he raped Desiree Washington, a crime for which he served prison time, said he now wishes he had. Cubs manager Dusty Baker and radio host cum football commentator Rush Limbaugh made ignorant racial comments.

Golfer Vijay Singh sounded like a petulant 2-year-old, at best, when threatening to withdraw from a tournament at which Annika Sorenstam — a girl! — had been invited to play. Masters chairman Hootie Johnson sounded about the same in his continued public whizzing match with activist Martha Burk over allowing women to become members at Augusta National. Burk didn’t come off looking much better.

And then there were those who let their actions do the talking. Randall Simon of the Pittsburgh Pirates playfully whacked a woman in a racing sausage costume with a baseball bat in Milwaukee. Bill Romanowski of the Raiders — one of the four reported to have tested positive for THG — not so playfully beat the tar out of teammate Marcus Williams, sidelining him for the season and prompting a lawsuit. During a playoff game, elderly, rounded Yankees coach Don Zimmer took a less than sane run at Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez, who had just beaned Yanks journeyman Karim Garcia, and Zimmer paid for it with a body slam to the turf.

He stood nearly alone among the bad actors in apologizing later and appearing to mean it.

Even Pete Rose, that old gambler, reemerged, the debate about whether he should be reinstated to baseball and elected to the Hall of Fame rising to the level of both an ESPN mock trial and rumors that Rose had reached an agreement with commissioner Bud Selig. It was as though Rose were brought onstage to remind us that misbehavior’s not a new thing, misbehavior started long ago.

The Portland Trail Blazers, meanwhile, seemed to exist solely to remind us that it’s alive and well in the present.

But it wasn’t all darkness. Championships were won, legends begun and ended, reputations polished, brilliant performances turned in.

Septuagenarian baseball trouper Jack McKeon came out of retirement to lead the Florida Marlins from a dismal start to a dashing World Series upset of the Yankees, the bigger upset being that the club wasn’t broken up at the trading deadline. Along the way the Marlins, especially rookie flash Dontrelle Willis, rejuvenated star catcher Ivan Rodriguez and McKeon, reminded us that hardball can be a mess of fun.

And so did the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox, who both tantalized their fans by falling just short of the World Series. The Red Sox, a rough-and-ready bunch that scored runs in bunches, may have been the most entertaining team of the year in any sport as they fell one win short of the Series, where they would have had a chance at their first championship since 1918, when Babe Ruth was their star. In the end they were beaten in extra innings by a far lesser figure, Aaron Boone, who won the pennant with a home run that will take its place in the one-sided history of the Sox-Yankees rivalry.

Cubs fans, without a title since 1908 or even a pennant since 1945, shook their heads and muttered about curses after Walkman-wearing fan Steve Bartman entered the language by trying to catch a foul ball that Cubs outfielder Moises Alou had a chance of snaring in Game 6 of the National League playoffs. The Cubs, five outs away from the pennant, melted down and blew their lead in that game, then lost Game 7 to the Marlins. But since Bartman only did what any fan would do, he’s not on our list of the year’s misbehavers. And neither is Cubs shortstop Alex Gonzalez, the real culprit for Chicago’s collapse in that fateful eighth inning for booting a crucial ground ball. He can thank Bartman for Cubs fans not wanting his head on a platter, but his was a physical error, not a bad act.

The Tampa Bay Buccaneers hardened into a juggernaut at playoff time in January, culminating in a Super Bowl dismantling of the Raiders that was nothing short of breathtaking. But both teams wheezed through the 2003 season.

Goalie Jean-Sebastien Giguère put the Anaheim Mighty Ducks on his back and led them to an improbable Stanley Cup Finals berth, where they lost in seven games to the New Jersey Devils, the masters of a defensive system largely responsible for NHL hockey becoming nearly unwatchable in recent years. It’s not unwatchable outside, though, at least according to the 57,000 fans who showed up last month in Edmonton at the first outdoor regular-season game in NHL history, one that seems likely to signal the start of a trend.

Andy Roddick emerged as an American tennis superstar. Michael Jordan’s career ended, with a fizzle more than a splash, and then he was unceremoniously fired as an executive by the Washington Wizards, but we did get the odd flash of greatness. Eric Gagne of the Los Angeles Dodgers had a nearly perfect season as a relief pitcher. Albert Pujols of the St. Louis Cardinals had a third straight astonishing year at the start of his career. Barry Bonds had something of an off year for him, though it was still better than most of the years almost anyone else ever had, especially considering he put it together while dealing with the final illness and death of his father, Bobby.

The Connecticut women’s basketball team, led by Diana Taurasi, had its win streak ended at 70 but still won its second straight NCAA title, and underdog Syracuse rode freshman Carmelo Anthony to the men’s crown. Rice won its first NCAA championship of any kind when it took the College World Series.

The nice story of the year was David Robinson, elder statesman and upstanding citizen, winning the NBA championship with his San Antonio Spurs in his last season. Robinson served as a complement to the brilliant Tim Duncan, also a model of comportment and the Spurs’ leader.

But the basketball story of the year was LeBron James, first as a barnstorming, nationally televised high school star, then as the top draft pick of the Cleveland Cavaliers. The 18-year-old was the flag bearer for what might be called the Year of the Child. Because of him regular-season high school games were nationally televised for the first time. He’s a pro now, but the practice has carried over to the new season. Michelle Wie made the cut in six of seven LPGA tournaments and Freddy Adu signed a multimillion-dollar contract to play for D.C. United of Major League Soccer. They’re both 14. ESPN televised nearly the entirety of the Little League World Series, the preteen players approaching both the games and the surrounding media crush like pros. Mark Walker signed a shoe contract with Reebok. Mark Walker is 3.

James has so far been a delight, living up to his advance notices and revitalizing a long-moribund franchise in every sense other than, so far, wins and losses. But even King James edged close to a life of sporting crime. He flirted with suspension or banishment throughout his senior year of high school, obviously benefiting as he was from his status as a star athlete. The $50,000 Hummer his mother managed to buy him will be a part of his legend long after it’s been replaced by several generations of much pricier rides.

But the memory of 2003 that we should carry into the future is that of the Detroit Tigers, who in their bumbling way provided the best example of what’s good about sports when sports are good. Thanks to years of incredibly bad management, this team was so thin on talent that it spent the entire season rocketing toward a record-setting level of futility, the most losses in the modern history of baseball, more even than the 1962 New York Mets, who fell 120 times and became literally synonymous with losing.

But it didn’t happen. With six games to go, two against the Kansas City Royals and four against the Central Division champion Minnesota Twins, the Tigers were 38-118 and had to go 4-2 just to tie the ’62 Mets in the loss column. (The Mets were rained out twice and finished 40-120.) The Tigers had to go 5-1 to avoid the record books. They’d lost 10 straight games, all by at least two runs and all but two of them by at least four. It had taken them 24 games to collect their most recent five wins. In short, this was not a team capable of winning five times in six games.

They beat the Royals twice and won the opener against the Twins before losing for the 119th time, one shy of the record. On the second to the last day of the season, they fell behind 8-0, then rallied to win on a wild pitch in the bottom of the ninth. They won again in the season finale to avoid the record. It was the most inspiring rally of the year, even though the games were entirely meaningless in the standings.

Watching the Tigers celebrate as though they’d won the World Series, especially after that penultimate game, offered a lesson for sports fans depressed by this year of malefaction and delinquency: No matter how bad things get, sports can still provide those amazing moments of joy, release and celebration.

It was a necessary lesson, because in 2003, things got really, really bad.