Sixty miles east of Columbia on the Strom Thurmond Highway, the Darlington water tower rises high above cedar swamps and cotton fields. The word "Darlington" is painted high on the water tower, right next to the NASCAR logo.

There's a raceway here in Darlington, and on every Labor Day for 54 years race fans have poured into town for the Southern 500. It brings in a lot of money, that race, and the town is grateful for it. Signs all over Darlington say "Race Fans Welcome Here." The police cars are painted with checkered flags.

But you don't find a lot of NASCAR dads here, at least not on a February day when the raceway is quiet and the Southern 500 seems a long way off in the rear-view mirror. What you find are guys like Bernard Ervin: He's 43, a father of five, and black. Ervin used to work in the factories and mills around Darlington. But since George W. Bush became president, he has been laid off three separate times.

"Ever since Bush has been in there, it seems like having a job don't mean nothing anymore," Ervin says. "You can have a job one day, and you can get laid off the next day." Ervin works as he talks, dishing out barbecue and slaw inside his parents' ramshackle little restaurant where he helps out, waiting for something better to come along. He's hoping the Democrats bring it.

This is the good news for Democrats in the South. As the race for the Democratic presidential nomination goes national this week with primaries from South Carolina to South Dakota and from Delaware to Arizona, black Southern voters are focused sharply on the troubled economy -- the loss of jobs, the lack of opportunity -- and they're holding George W. Bush responsible for it.

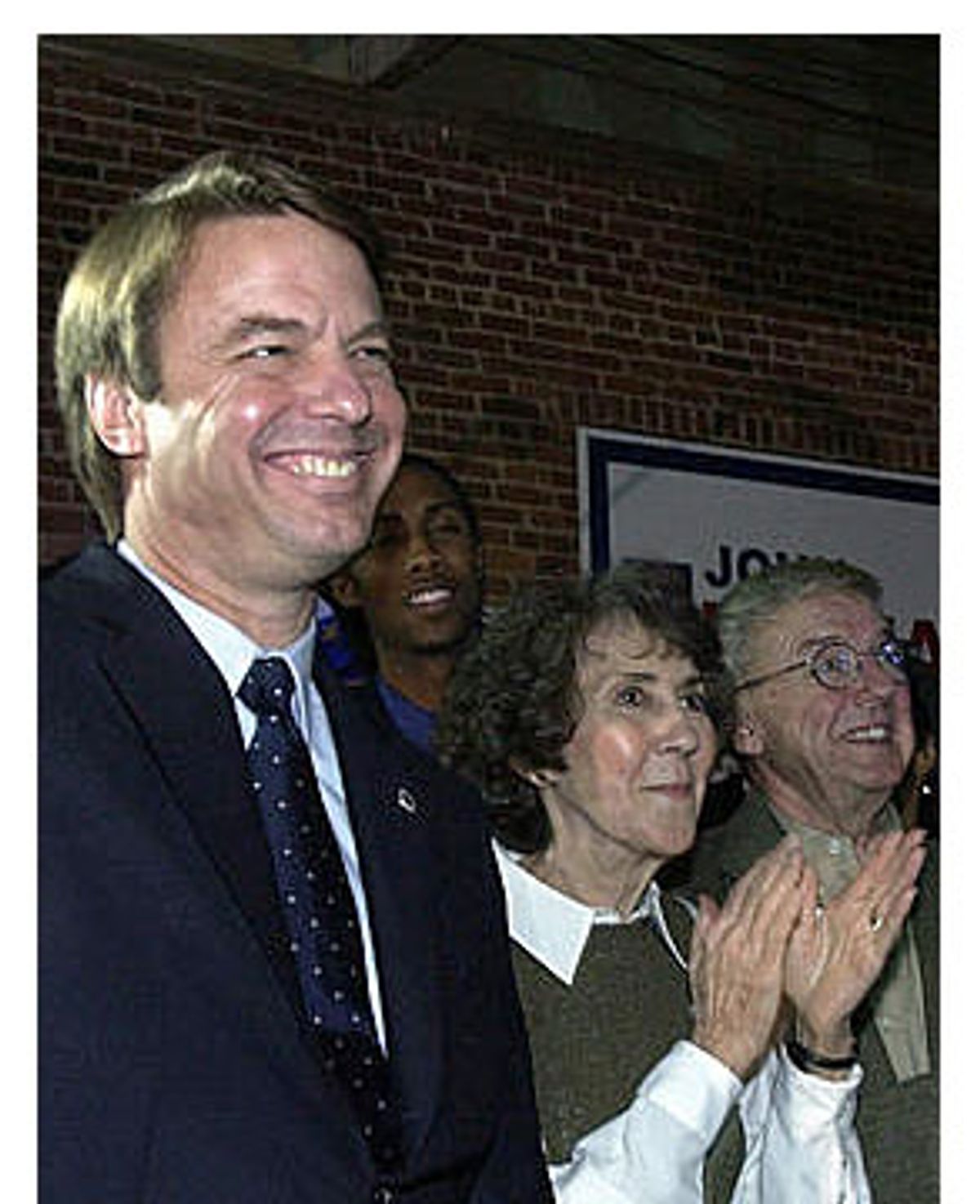

But that's only half the story. People like Chris Newman are the other half. Newman is 21, white, and a senior at Francis Marion University in Florence, S.C., just up the road from Darlington. North Carolina Sen. John Edwards pulled into Francis Marion for a campaign appearance last week. But as Edwards fired up a couple hundred supporters with his "two Americas" stump speech, Newman was picking up his baseball glove and heading off for practice. "I voted for Gore, but I'd probably vote for President Bush if I had to do it again," Newman says. "I like that he's a Christian and that's he's not afraid to admit it. I can relate to that."

And that's the problem for Democrats in the South this election year. While African-American voters may be solidly on the "Anybody but Bush" program, many white Southerners -- even some who voted for former Vice President Al Gore in 2000 -- can "relate" to Bush and plan to vote for him in November. They see in the president a man like themselves: a Christian who shares their political views on issues like abortion and homosexuality, and a red-white-and-blue patriot who stands with them in supporting the men and women in the U.S. military.

"Bush is immensely popular with white voters in the South," says Jack Fleer, professor emeritus of political science at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C. "He makes a big issue of his religion, and that's a very big thing in the minds of many Southerners. And despite his limited service in the military, he really buddies up to the military, and that's important in the South."

And what's important in the South, Fleer says, ought to be important to the Democrats. While it's mathematically possible for the Democrats to win the presidency without winning the South -- a point Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry made last month in language that caused some to speculate he would ignore the region in his campaign -- it's a whole lot easier to win the White House with the South than without it. And appealing to voters here is important for at least two other reasons, Fleer says. First, the sort of moderate views needed to win the South will also help win over swing voters elsewhere. Second, he said, if the Democrats run a candidate who can't compete in the South, they'll risk losing not just the presidency in November but also five Southern Senate seats the Democrats hold but that are in danger of going Republican.

"Democratic candidates ran away from Dukakis in 1988 and McGovern in 1972," Fleer said. "It could well be the case that you would make the campaigns for the Democratic Senate candidates much more viable if you had a presidential nominee with whom people can comfortably run."

That may be easier said than done. The Republicans have dominated Southern politics since the 1960s, when the party began distancing itself from its prior support for civil rights for African-Americans. Jimmy Carter took the South in 1976, and Bill Clinton carried four Southern states in 1992 and 1996. The South has been otherwise impenetrable for Democrats since the reign of Lyndon Johnson. Al Gore couldn't even carry his home state of Tennessee in 2000.

Traveling through South Carolina in the weeks leading up to Tuesday's primary, it's hard to miss reminders that the South remains distinctly different -- more religious, more patriotic in the flag-waving sense -- than bicoastal, blue-state America, a place where it will be hard for even a moderate Democrat to play well.

Jesus seems to be on every other radio station, and Dr. Laura Schlessinger is on the rest. Newspaper editorial pages feature daily Bible quotations, and the dreamy teen making lattes in Charleston is wearing a church T-shirt over his low-slung corduroys. In a funky coffeehouse in a Columbia basement, a hipster kid with a guitar is doing a mock-earnest version of Kenny Rogers' "The Gambler" that somehow comes out achingly beautiful, but he's playing on a stage that sits under a huge American flag.

The differences are subtle, sometimes, and then sometimes they're not. Outside the Democratic presidential debate in Greenville last week, two burly guys walked up and down the street carrying Confederate flags. Another stood silent sentry a few feet away from a pack of Kerry supporters, literally wrapped in the Southern Cross. A young family moved through the crowd carrying signs that said, "God save Dixie from D.C."

Joshua Greenwood, a 24-year-old mortgage broker, stood his ground outside the debate holding a sign in which he listed people who had run on "the hate ticket": Adolf Hitler, Saddam Hussein, Howard Dean, John Kerry and John Edwards. "I support George W. Bush," Greenwood said, just before he began jostling for position with a supporter of Sen. Joe Lieberman who tried to block Greenwood's sign from the view of TV cameras taping Lieberman's arrival at the debate site. "The Democrats are trying to tear down the morals of this country."

You hear a prettier version of the same story on Sunday morning at the Forest Drive Baptist Church in Columbia. It's about half an hour before services are to begin, and a few women are sitting around a table in the immaculate church hall. Ask them what issues are important to them in 2004, and they say "issues involving people." Ask them if members of the church are mostly Republican or mostly Democrat, and they say they have absolutely no idea. But spend a few minutes with them, and their opinions and their allegiances become clear. They like the president -- they pray for the president -- because he's a man of God. "Without having a man who can hear from God, the country can't be run right," says Melissa Penney. Do any of the Democratic contenders hear from God? Penney says she doesn't know. "If they're Christians, they do," she says.

Forest Drive Baptist is a mixed-race church, but Penney is the only African-American in the small group of women talking around the table. After she walks away, Anne Abel begins to talk about her thoughts on the Democratic primary Tuesday. It's an open primary. And while Abel generally votes Republican, she is thinking about crossing over to vote for what she considers the lesser of the evils among the Democratic contenders.

"There are a couple of candidates I strongly oppose in that I think that their positions would be dangerous for our country," says Abel, who works in an assisted living facility for senior citizens. "So if I feel that the Lord gives me the freedom to [vote in the primary] and I feel like I can do that, I would probably vote for one of the other ones."

She doesn't name names at first, but she eventually says that she's particularly concerned about Sen. John Kerry because of his "liberal stance on gay marriage and abortion." Told that Kerry -- like all of the major Democratic contenders -- actually opposes gay marriage, she points to the fact that the highest court in Kerry's home state of Massachusetts has ruled in favor of gay marriages. And, she says, "The fact that Senator Ted Kennedy has endorsed him highly concerns me."

With the exception of Al Sharpton, who isn't going to be his party's nominee, there isn't a Democrat in the field who can outdo George Bush when it comes to God-talk, at least in the eyes of the born-again Christians who play such an influential role in Southern politics. Howard Dean and Wesley Clark have both tried, without much success. Lieberman impresses Southern Christians as a serious religious man, but the wrong kind. While John Edwards plays up his status as a Southerner -- in his stump speech, he says that the South "isn't George Bush's backyard, it's mine" -- he has not wrapped his rhetoric in the language of the faithful. And Kerry mentions faith nearly never. Indeed, he has said: "I don't make decisions in public life based on religious belief."

Kerry supporters hope they can win over Southern voters in other ways. Kerry's campaign has flooded South Carolina with veterans and firefighters who support his candidacy, hoping that their presence in the state will give comfort to Southern voters who sometimes see the Democrats as the party of wimps.

And Fleer says that Democrats may be able to make inroads with white Southern voters if they can begin to persuade them that it is Republicans -- not Democrats -- who are fiscally reckless. Howard Dean made just such an argument at the debate in South Carolina Thursday night, pointing out that recent Republican presidents had run up huge deficits while Bill Clinton balanced the federal budget. Fleer would like to see more of the same, even as he acknowledges that it's a "counterintuitive" argument for voters conditioned to think of Democrats as "tax and spend" liberals.

The trouble is, economic issues don't seem to trump the cultural issues that are important to many Southern white voters. In part, at least, that's because some of them have simply not suffered much from the nation's economic woes. At Forest Drive Baptists, for example, the women gathered around the table say that most of the families in the church continue to do relatively well. There's a reason for that, says Susan Thomas, an elementary school P.E. teacher who is married to the church's senior pastor. "There's a verse in the Bible that say the righteous, you'll never see them begging for anything," says Thomas. "Honestly, God has been very gracious to many of our people, in preserving them. We find that yeah, we have some tough times and some tough stuff ... but God has been so gracious, and our church has been very blessed."

Those same blessings haven't reached everywhere. The unemployment rate hovers around 20 percent in some South Carolina counties, especially in places where mills have closed or companies have taken jobs overseas. At campaign stops in these places -- where the audiences are mostly if not exclusively African-American -- no one seems interested in hearing about anything other than the economy.

"I'm looking for a president who's for all the people," says Shenell Floyd, a 28-year-old college student and call-center worker who turned out to see Edwards and a representative for Rep. Dennis Kucinich speak at Allen Temple AME Church in Greenville last week. "I want to see where the candidates really stand on getting jobs and helping people."

Even questions about the war in Iraq come wrapped in economic worries. At a candidates' forum in Greenville last week, Elaine Johnson held a framed photograph of her son, Darius, a soldier in the U.S. Army killed last November when a missile struck his helicopter near Fallujah. Johnson is angry about the war -- she referred to it as "unjust" -- but that's not what she wanted to discuss with the candidates. She wanted to ask what they were going to do about the economy, how they were going to make sure that a young man or woman graduating from high school has options other than military service. "Young people should join the military because they want to be soldiers, not because there are no jobs," Johnson said when she had the chance to put a question to Edwards.

And out in Darlington, Bernard Ervin is also concerned about the war in economic terms. He knows that Congress has given President Bush $87.5 billion to fight in Afghanistan and Iraq -- that number, that $87.5 billion, has a way of sticking in the minds of people who otherwise don't pay much attention to federal budget issues -- and he wonders why there isn't money like that to help people like him.

"All that money going by in the war," he says, shaking his head. "When small businesses around here go looking for loans, it's not there. When people around here go looking for help, they can't get it. There's something wrong with that."

Shares