In a recent article in Dissent magazine, Paul Berman -- the quixotic American intellectual and self-defined leftist who has loudly supported the Bush war in Iraq -- proclaims that he is not in fact alone. His views are shared, he writes, by British Prime Minister Tony Blair, "who is a socialist, sort of."

One might uncharitably argue that this is just more evidence that Berman has snapped the tether. Or, to be more specific, that he has drunk so much of Paul Wolfowitz's Kool-Aid he's starting to hallucinate. (He goes on to explain that Saddam Hussein is indeed connected to al-Qaida, and that the secret link between them is, more or less, Adolf Hitler.) But the "sort of" suggests that Berman is trying to be funny. He's too smart not to understand this as a sort of macabre political joke. It's like observing that George W. Bush belongs to the party of Abraham Lincoln -- it possesses a certain technical or historical correctness, without actually meaning anything.

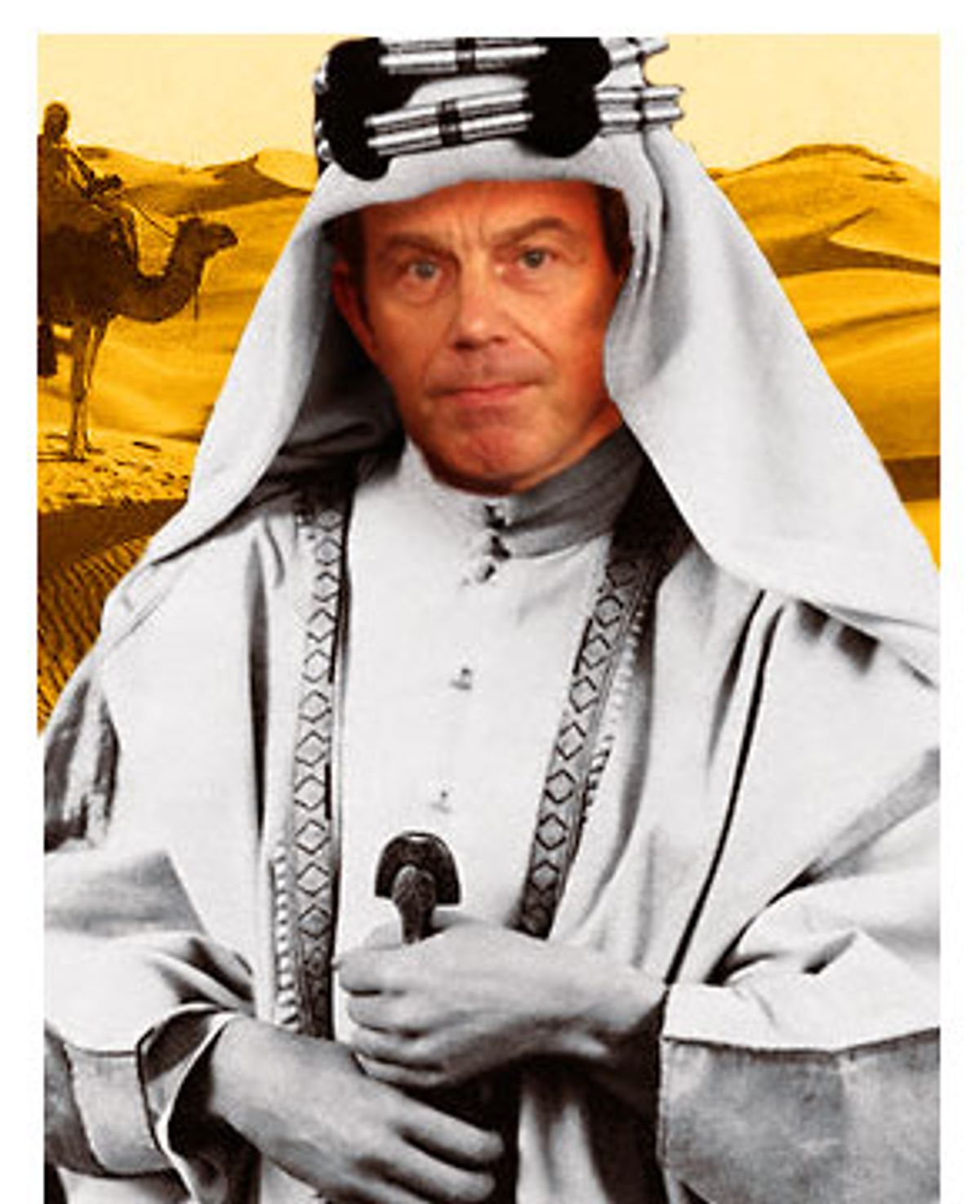

If the beleaguered Tony Blair might be flabbergasted to be described as a socialist at this late stage, it's better than some of the other things he's been called lately. This Clintonesque warrior of the center, an Oxford-educated lawyer who breathed new life into the moribund Labor Party and presided over a British mini-Renaissance at the end of the '90s, wound up loyally following George W. Bush into Baghdad, and may have scuttled his impressive political career along the way. In the vernacular of the ever-vicious Fleet Street press, Blair has become Bush's "poodle."

Blair's government has been exonerated, at least officially, of the charge that it "sexed up" intelligence documents regarding Saddam Hussein's alleged weapons of mass destruction. But the fact remains that the British intelligence dossier of September 2002 that was used to argue that war was necessary -- and was heavily relied upon by Bush and Colin Powell -- was profoundly flawed, and was presented in what may generously be described as a distorted and misleading fashion. The charge that Iraq had tried to purchase uranium from Niger was almost certainly false (and would have been insignificant had it been true). The headline-making allegation that Saddam could have biological or chemical weapons ready to launch in 45 minutes referred only to battlefield tactical weapons, not to missiles aimed at Israel or the West, a distinction Blair now says he never understood. (And as far as anyone can tell now, that one wasn't true either.)

Blair's masters in Washington, counting on the ever-distractable nature of the American voter ("You're such a cute baby! Now look over here -- ooh, what a scary gay marriage!"), are pretending they never said anything about WMDs. But Blair has remained out there by himself, shivering in the wind, pathologically unable to let go of all the misinterpreted and half-baked evidence that paved the way for George and Tony's not-so-excellent Iraq adventure.

Some point of pride is clearly involved: Rather than apologizing or prevaricating, Blair keeps insisting that he was right all along and that the truth will come out, even as scandal after scandal -- a plagiarized Ph.D. dissertation, a scientist dead in the woods, evidence of Anglo-American spying at the United Nations -- crashes over his government.

Yet Blair's former foreign secretary, Robin Cook, who resigned from his Cabinet position to protest the Iraq war decision, suggests that the prime minister is not being honest about his own beliefs. In the most damaging passage of his extraordinary memoir "The Point of Departure" (a book that should be read by anyone interested in the global fortunes of the electoral left), Cook writes that he told Blair, on March 5, 2003, that "Saddam did not have real weapons of mass destruction that were designed for strategic use." Blair made no effort to contradict him. "What was clear from this conversation," Cook writes, "was that he did not believe it himself."

What is clear from Cook's book, and from Philip Stephens' fascinating new Blair biography aimed at American readers, is that Blair has compelled himself to believe he did the right thing in Iraq, and did it for the right reasons. If he is misleading the world, and perhaps even himself, about what he knew and when he knew it, it's because he needs to think of himself as an independent-minded liberal interventionist driven by "a melding of strategic calculation and moral fervor," in Stephens' phrase, rather than, say, a spineless transatlantic toady who got steamrollered by the neocons in Washington. (In much the same way, Paul Berman needs to see himself as the last noble leftist fighting global fascism, rather than, say, a lonely crank who believes that no one understands the world except him and Christopher Hitchens.)

Using the standard British synecdoche for the prime minister's office (located in the 18th century townhouse at 10 Downing Street in London), Cook writes, "Number 10 believed in the [September 2002] intelligence because they desperately wanted it to be true. Their sin was not one of bad faith but of evangelical certainty." That certainty has characterized Tony Blair's entire career. It catapulted him to the leadership of the rudderless Labor Party, drove him to remake it in his own image and brought him, in 1997, to the doorstep of Downing Street. It tied him first to Bill Clinton and then to George W. Bush. Now it might be his undoing.

Recent polls indicate that two-thirds of Britons believe Blair lied to them about the reasons for war, and half think he should resign. For the first time in Blair's seven years in office, the battered Conservative Party is back in a semi-competitive position; it may mount a credible challenge by the next general election (in 2005 or 2006). It's undoubtedly too soon to write Blair's political epitaph, but public trust in his government has been chewed to splinters, and any further scandal could lead his own party to depose him. His Iraq escapade drew open opposition from 139 Labor members of Parliament (about one-third of the total), but the de facto dissent was much higher than that, and dissatisfaction at the Labor grass-roots is widespread. For a politician until recently seen as an untouchable golden boy, who seemed likely to be one of the longest-serving prime ministers in modern British history, the fall has been dizzying.

Cook and Stephens (who is an editor at the Financial Times) have both known Blair for years, and the portraits they paint of this ambitious and accomplished politician are generally consistent. Both seem to admire and respect him, almost despite their better judgment. Both believe that his impressive domestic accomplishments have been all but obliterated by the Iraq debacle, and that Blair has become so estranged from the core supporters of his own party that his political legacy is problematic at best.

Both authors agree that the roots of Blair's current predicament lie in the contradictions of his personal and political character. Inevitably, though, his crisis also results from the tenuous position occupied by any British prime minister of the post-World War II era, poised uneasily between America and Europe. Faced with a confrontation between Bush on one side and the U.N., Europe and the overwhelming weight of world opinion on the other, Blair bet everything on his ability to defuse the conflict and find common ground. (Compromise and an almost miraculous ability to enfold opposing points of view, after all, have been the hallmarks of his political style.)

Needless to say, there was no common ground to be found between Dick Cheney and Jacques Chirac (except for the fact that both, it seems, dislike Blair intensely). When the United States and Britain failed to win a U.N. resolution authorizing war last March, Blair was left with no way out. In the "special relationship" between the two Atlantic allies tied together by blood, history and language, it's always been clear who's the daddy and who's the punk.

In his brisk and judicious "Tony Blair: The Making of a World Leader," Stephens argues that the prime minister saw himself as a crucial member of the Bush coalition, a rational multilateralist who could counterbalance the cowboy recklessness of Bush, Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld. In this account, Blair held out hope until late in the process that Saddam might capitulate to the U.N. in a manner that would satisfy the Americans and avert war; Blair says he told Bush they had to be prepared "to take yes for an answer." But Blair deluded himself, Stephens writes, about the amount of influence he actually possessed, and violated two cardinal rules of politics: "Never take risks when someone else determines the outcome, and avoid responsibility when power resides elsewhere." (That actually sounds like two ways of stating the same rule, but never mind.)

In Cook's wide-ranging, humble, funny and wise memoir -- if only we lived in the alternate universe where this urbane Scottish leftist, and not his sanctimonious former boss, was a "world leader"! -- he agrees with this analysis, but only up to a point. In the same March 2003 conversation mentioned above, Cook writes, Blair defended his role by saying, "Left to himself, Bush would have gone to war in January. No, not January, but back in September."

But Cook's entire book -- which comes, after all, from an insider -- is underpinned by his more cynical perception that Blair always knew how all this would end. Bush and his cronies had made up their minds, and the British government would do as it was told. The role of the eloquent Oxonian was to be the coming war's friendly face, and to make it look as much as possible like a noble cause supported by a genuine multinational coalition. In Cabinet meetings, Cook writes, "Tony made no attempt to pretend that what Hans Blix might report would make any difference to the countdown to invasion." In other words, contrary to everything Blair ever said in public, the U.N. inspections of late 2002 and early 2003 were strictly for show.

Cook believes it never occurred to Blair that a prime minister who dared to defy a warmongering U.S. president -- as Harold Wilson did in the late 1960s by refusing to send British troops to Vietnam -- would be viewed as a hero at home, in Europe and around the world. As always, his thinking was both moral and strategic. No one disputes Blair's conviction that the world would be a better place without Saddam Hussein's regime. His credentials as a humanitarian interventionist, unlike George W. Bush's, are genuine. A few years earlier, Blair was perhaps the principal architect of NATO's war against Slobodan Milosevic, gradually coaxing Bill Clinton into the sustained bombing campaign -- and the threatened ground invasion -- that finally forced the Serbian leader to yield.

But unlike Stephens, Cook does not think Blair was primarily motivated by a grand global purpose in Iraq. The real mortar in the improbable alliance between Blair and Bush, to use his metaphor, is political power. "It is a fixed pole of Tony Blair's view of Britain's place in the world that we must be the No. 1 ally of the U.S.," he writes. "I am certain that the real reason he went to war was that he found it easier to resist the public opinion of Britain than the request of the U.S. President."

Tony Blair's distinctive combination of somewhat priggish moralism and raw political calculation, coupled with his lack of an identifiable ideological base, constitute both his greatest asset and greatest liability. If that sounds familiar to American observers, it should.

Consider the following. Blair was a brilliant young lawyer married to another one, a splashy, controversial woman who is sometimes deemed to be the ideological driving force in the household. (Cherie Blair was openly upset about her husband's decision to befriend George W. Bush after the divisive 2000 election, wondering aloud during a flight to Washington why the Labor government should be nice to "those people.") Both had political ambitions, but the couple decided the electoral realm had room for only one of them at a time. (The Blairs agreed that the first of them to be elected to Parliament would get the other's support. Both ran in the 1983 general election, but Tony was awarded a solid Labor district, while Cherie faced an unbeatable Conservative incumbent.)

Whatever his faults may be, Blair is a born politician, an energetic and charismatic performer. He quickly rose to the top of a listless center-left political party that had spent a generation in the doldrums, while right-wing radicals had reshaped society. He drove out the party's most ossified elements, put a halt to its endless infighting and brought it back into power. His manner is personable, ingratiating and non-ideological; his message is carefully calibrated to appeal to the expanding middle class that thinks of itself as neither liberal nor conservative. His stated goal, however, was ambitious: the creation of a new social compact, focused equally on rights and responsibilities, that will split the difference between the social-democratic vision of equality and the free-market vision of unfettered individualism.

OK, you know where I'm going with this. But wait, there's more. Blair's first term in office was strategic and cautious, mainly focused on establishing confidence in his government's competence. It worked, or at least it worked enough. Although beset by minor squabbles on both the left and right, he was reelected comfortably. But in his second term, when a political leader is supposed to be set free from narrow political concerns to build his historical legacy, the wheels came off.

Maybe this is forcing a point too far, but Blair has now been enmeshed in a crisis that is largely of his own creation (but has been magnified by his enemies). He has barely survived a humiliating legislative vote and now seems to be limping, gravely wounded, toward the end of his political career. His once-vaunted "Third Way" politics now look like a set of buzzwords past their sell-by date. Many in his own party wonder whether he has led them into a bottomless swamp of compromise where they have lost touch with their core values and core supporters.

As alluring as these similarities between Tony Blair and Bill Clinton may be -- and as much as these two friends tried to cultivate the notion that together they commanded a new political tide -- the differences between them may be more instructive. Clinton's presidency was undone by his own personal failings, and by the ruthless attacks of ideological opponents who gleefully seized upon his philandering and mendacity. Blair, by all accounts, is a man of tremendous rectitude, who until recently has faced little serious political opposition.

Under Britain's parliamentary system, Blair has had full control of government for seven years, something Clinton could only dream about. As a result, even his worst enemy of the right or left would have to agree that his accomplishments have been impressive. He transformed the national mood, helping to create an optimistic boom climate in the late '90s that led to London's international recognition as a vibrant capital of fashion, design and (incredibly) cuisine.

With Clinton's help, Blair forged a provisional peace in Northern Ireland after 30 years of civil war. Regional assemblies for Scotland and Wales, and various wonky but significant constitutional reforms, have brought Britain's antiquated mode of government into the modern age. Under the radar, there was even some "old Labor"-style socialism (as Cook calls it, "social justice by stealth"). Funds were quietly poured into public education and the National Health Service -- repairing at least some of the sabotage of the Maggie Thatcher-John Major era -- and new government subsidies have lifted thousands of low-income children and elderly people out of poverty.

As Cook discusses, Blair, like Clinton, has had a tendency to rub left-leaning grass-roots activists of his own party the wrong way. This may be a necessary corollary of mainstream electability, but it has had the peculiar effect that both men have neither claimed nor received credit for some of their most progressive endeavors. (Here again, though, the difference between the political cultures of the two nations is striking: No serious participant in British political life could support the death penalty, oppose legal abortion or argue for any healthcare system other than the government-run National Health Service.)

Blair has exacerbated the problem by deliberately distancing himself from the great tradition of the 20th century Labor Party. His hero is not Harold Wilson, or James Ramsay MacDonald, the illegitimate son of a servant who became Britain's first socialist prime minister, or Clement Attlee, the architect of the postwar welfare state. It isn't even David Lloyd George, the Liberal Party radical who pointed Britain on the road to industrial democracy after World War I.

Instead, as Stephens discusses at length, Blair's professed model is William Gladstone, the ruling-class Tory-turned-Whig who became the great social reformer (and great international interventionist) of the Victorian age. Now, Gladstone was a remarkably progressive figure -- by the standards of the 19th century British Empire. Blair's grandiloquent self-comparisons to Gladstone smack simultaneously of Kipling-esque nostalgia, an inflated sense of his own significance and a startling lack of historical perspective. Gladstone was the political leader of a mighty military empire on which the sun never set; he was clearly among the two or three most important world leaders of his day. Tony Blair is the premier of a cute little island nation on the edge of the Atlantic that can't decide whether to be an American adjunct or the third most important country in Europe.

The Gladstone analogy suggests that Blair's strategic decision to hew close to George W. Bush, and perhaps moderate the wacko policies of the neocons around him, went hand in hand with Blair's desire to be a force on the global stage and make his mark on history. The tragedy of Tony Blair lies in the fact that the very qualities that allowed him to revamp Labor and rescue Britain from the Tory death-grip also led him to defy the U.N., his own public, the great mass of world opinion and probably the wishes of his own wife, and bet everything on an ill-considered war that was almost guaranteed to make him look bad. (One Machiavellian possibility, which Cook briefly entertains, is that the Bush White House predicted that one way or another Blair would come out of Iraq with egg on his face -- and was delighted at the prospect.)

During Bill Clinton's last, rueful presidential visit to Chequers, the prime minister's country house, in December 2000, Stephens reports that Blair asked Clinton how he should deal with the incoming President Bush. "Be his friend," Clinton reportedly told him. "Be his best friend. Be the guy he turns to." Not even the genius political mind of Clinton, one suspects, could have imagined where that friendship would lead. Many people on both sides of the Atlantic have been mystified by the close relationship between the English social-democrat and the Texas born-again. (Both are practicing Christians, which makes Blair something of an anomaly in modern British politics, but Stephens and Cook both underplay this potential connection.) Cook reports telephoning former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright in the fall of 2002, as the Iraq crisis thickened. She asked him in disbelief: "Just what does Tony Blair think he's doing?"

As Cook muses repeatedly, if any other Labor politician had been living at No. 10 -- or, alternatively, had the hanging chads in Florida shaken out differently -- we would have had no war in Iraq, or at least not the disastrous one we got. (The question of whether any other Labor politician could have been elected in the first place can never be answered.) A passionate lifetime advocate for the power of international law, Blair has now done more than almost anyone on the planet to undermine it. "Nobody in their right mind would dispute that Iraq is a better place without Saddam," Cook writes. "But the world is most certainly not a safer place now that we have reasserted the unilateral right of one state to invade another."

It is far too early to render any final historical judgment on Tony Blair -- or on Bill Clinton. Historians and political scientists will publish books for decades to come about these two friends, their joint and separate efforts to respond to new political realities and fight for the political center, and their respective crises. But Blair's case is the one we see before us now, and in some ways it is the more dramatic and interesting of the two. No one interested in what will become of the left in the 21st century can ignore the story of his rise, and his fall.

Shares