When a car bomb ripped through the Mount Lebanon Hotel in Baghdad, Iraq, Wednesday morning, you might have expected the Secret Service to shuffle Dick Cheney off to a secure undisclosed location somewhere -- not because there was any immediate threat to the vice president, but because Wednesday seemed like the kind of day when the architects of the war on Iraq might prefer to be outside of the public view.

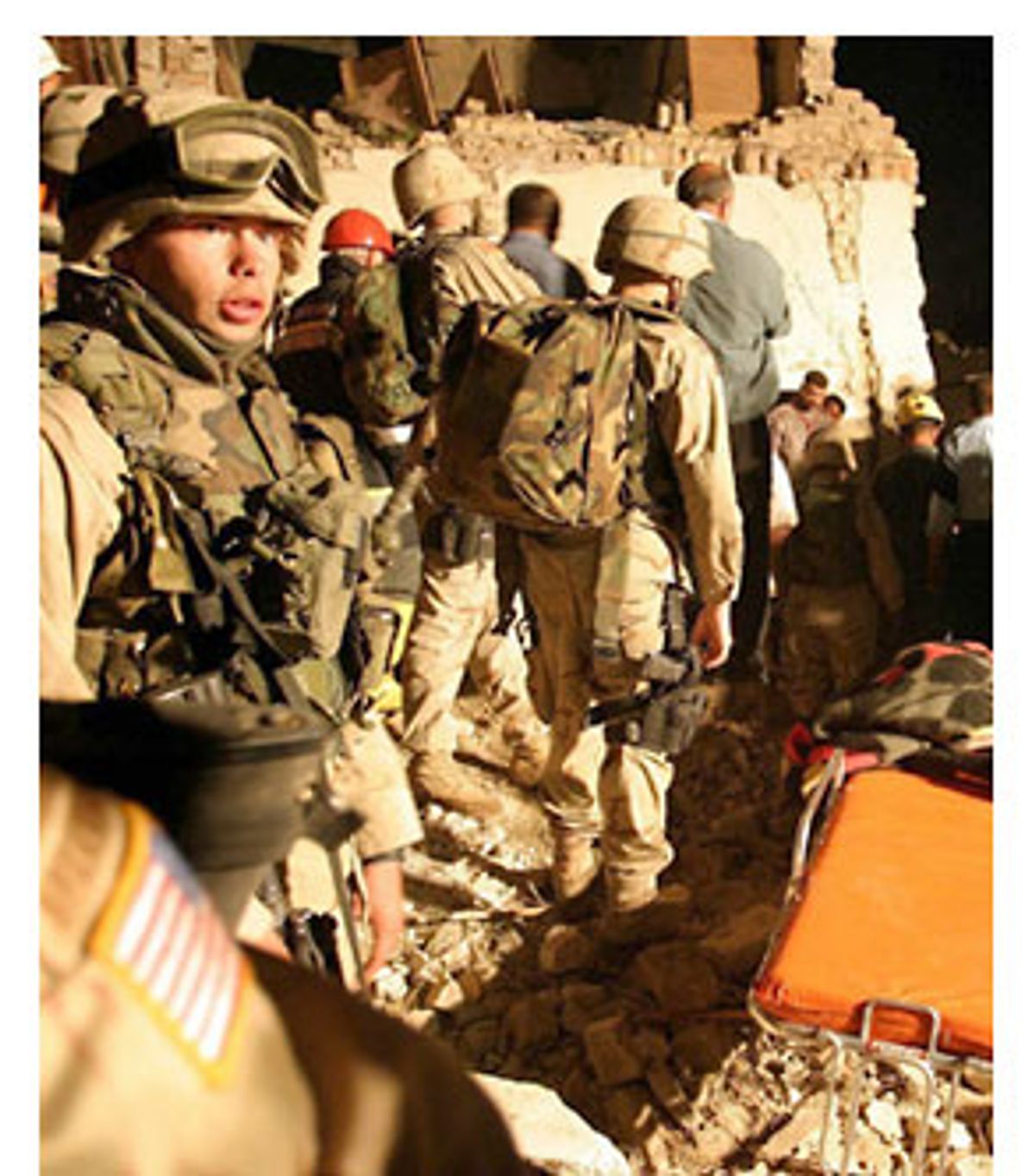

Not so. Minutes after the attack, which killed seven people and marked a bloody beginning to the one-year anniversary of the Iraq war, Cheney took to the stage for a previously scheduled speech at the Ronald Reagan Library in California. On one half of CNN's split screen, rescuers pulled bodies from the rubble in Baghdad; on the other half, Cheney blasted away at Sen. John Kerry's record on Iraq.

Chutzpah? Maybe, but there's more. On Thursday, George W. Bush himself traveled to Fort Campbell, Ky., to trumpet his administration's success in the war on terror on the eve of the anniversary of the beginning of the Iraq war. On Saturday, Bush will hold his first full-fledged political rally of the election year. The location: Florida.

From the blue state perspective of the MoveOn and Meetup world, it all seems exactly upside down. From that vantage, the war on Iraq has been an unmitigated disaster and international embarrassment -- 565 U.S. soldiers have died in a war whose primary proffered justification appears to have been false -- and it's a reason to vote against George Bush, not for him. But that's clearly not how they see things at Bush-Cheney headquarters. White House political strategist Karl Rove plans to run his client as a steadfast leader in dangerous times, and events like Wednesday's bombing in Baghdad and Thursday's attack in Basra may, paradoxically, help set the stage for such a campaign. New violence in Iraq pushes the war back to the top of the TV news, and it blows talk of a stagnating U.S. economy right off the air.

An all-war, all-the-time strategy is clearly a risky one for Bush: If Iraq goes south, Bush may go down with it. And every time Bush mentions Iraq, a significant percentage of mistrustful voters will be reminded of the misrepresentations the administration made in the run-up to the war. But given the sad state of the U.S. economy, what other issue can he hope to exploit? "I think this is the only path he can take," Rutgers University political science professor Ross Baker said Wednesday. "The problem is, it leaves him at the mercy of a lot of crazy people. If Bush wants to take credit for defending the nation against terrorism, he also assumes the burden of anything that may happen."

As the nation heads into a weekend of looking back at a year in Iraq, both Bush and Kerry are establishing general-election campaigns predicated on the idea that something will happen between now and November. In a speech delivered just before the bombing Wednesday, Kerry attacked the administration for not doing enough to make American citizens and American soldiers safer. It was Kerry's most detailed discussion to date of the war and terrorism, and he used the moment to slam Bush for not working more closely with other countries, for leaving the military stretched too thin, and for sending soldiers to Iraq without the body armor they need to protect themselves. If terrorists attack the United States or if the U.S. begins to suffer massive losses in Iraq, Kerry has laid the framework for blaming Bush.

The new White House campaign, meanwhile, almost seems designed for the moment when things get much worse. If dangerous times require the "steady leadership" of George W. Bush, as Bush's TV commercials say, then really dangerous times must require his help even more.

Last week's terrorist train bombings in Spain may or may not have led to regime change there, but the Bush team is betting that a new terrorist attack in the United States is unlikely to lead automatically to the president's demise in November. Americans tend to rally around their leaders during times of crisis -- Bush's approval ratings soared after the Sept. 11 attacks -- and even Democrats concede that voters might embrace Bush once more if terrorists strike here again.

"No one can answer that question until it happens," said Will Marshall, president and co-founder of the Progressive Policy Institute, a centrist Democratic think tank. "If it looks like a lapse in homeland security erected since 9/11, then the public will demand answers and it could really put the administration on the spot. But if the terrorists find a new way to hit us, I think the public will not blame the administration for that."

The effect of another attack may also depend on timing. "If an attack happens a week before the election, Bush wins," says Baker. "If it happens next week or in the middle of summer or on Sept. 11, it will give the Democrats time to say, 'You said you were going to protect us and you didn't.' The rally effect is intense but short-term."

Smaller setbacks in the war on terror or more trouble in Iraq may actually serve to help Bush's cause. While the blasts in Baghdad and Basra this week certainly underscored the fact that the U.S. mission still isn't accomplished there, they also focused the media on what is -- relatively speaking -- Bush's strong suit. A recent USA Today/CNN/Gallup poll shows that voters care more about the economy than they do about the war on terror right now, and they believe that Kerry, not Bush, would be the better leader on economic issues. While various polls show voters split or slightly negative on Bush's handling of the war in Iraq, the USA Today/CNN/Gallup Poll nonetheless shows that voters believe that Bush is better equipped to handle Iraq, terrorism and foreign policy generally than Kerry is.

As former Clinton advisor Dick Morris wrote in the Hill this week, Kerry and Bush "each owns an issue." Kerry wins on the economy; Bush wins on terrorism. Whoever can force the other to run on his issue may win the election. To the extent that Wednesday's attack forced Kerry to talk about something other than the economy, it's a good thing for Bush.

Marshall doesn't buy that. Focusing exclusively on the economy, he says, is the old Democratic approach, the one that proved devastating in the 2002 midterm elections. Kerry has got to engage on both the economy and national security. "War and security are on everybody's minds, and I don't care what the polls show," says Marshall, whose "third way" think tank has urged Democrats to take a more muscular approach on foreign policy. "Everyone is going to say that they care about the economy, but we're only one incident away from it being the No. 1 issue again."

Kerry may understand that, or he may feel compelled to speak out on the war to correct the lies the Bush camp is telling about him, or he may simply believe that he can fight Bush on two fronts at once -- hammering away on the economy while reminding voters that, if they can't trust the president to tell the truth about war, they can't trust him to tell the truth about anything else. That argument should resonate with a substantial portion of the electorate: A CBS-New York Times poll released last month shows that 57 percent of the public believes that the administration exaggerated intelligence in order to build support for the war.

That makes Bush's reliance on Iraq a little dicey, and it underscores the need for him to conflate the tainted Iraq occupation with the more popular war on terror. The administration tried to do that before the war, stretching to create some sort of meaningful linkage between Iraq and al-Qaida. While Bush seems to have disavowed those sorts of claims, some members of the administration persist. And Wednesday's bombing in Baghdad and Thursday's attack in Basra give the administration a bit more ammunition. Saddam Hussein may not have had anything to do with al-Qaida, but car bombs aimed at civilians in hotels certainly suggest that the United States is dealing with "terrorists" in Iraq now. "Whatever you thought about the wisdom of getting into Iraq, most Americans now believe that it has become a front on the war on terror," says Marshall. "And if it wasn't a front on the war on terror when we went in, it is now."

Cheney pushed that linkage hard Wednesday, calling the war on Iraq an "essential step in the war on terror" and claiming that the Spanish train bombings "may well be evidence of how fearful the terrorists are of a free and democratic Iraq."

While some of Cheney's speech was devoted to bolstering Bush's bona fides as a wartime president, Cheney spent most of his time at the Reagan Library assailing Kerry for this record on Iraq in particular and military affairs more generally. Cheney attacked Kerry by name 25 times. He mentioned Osama bin Laden exactly once.

Delivered with a biting sarcasm that went beyond Cheney's usual involuntary smirk, the speech was the administration's most detailed critique yet of Kerry's foreign policy views. In a line of attack that will resonate even with some Democrats, Cheney criticized Kerry for his evolving -- Cheney would say contradictory -- positions on Iraq. Kerry voted against the resolution authorizing the 1991 Persian Gulf War, then voted for the 2002 resolution authorizing Bush to use force in Iraq, then voted against legislation providing $87 billion in funding for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"Whatever the explanation, whatever the nuances he might fault us for neglecting, it is not an impressive record for someone who aspires to be commander in chief in this time of testing for our country," Cheney said.

The White House plainly sees a target of opportunity in Kerry's record on Iraq. By attacking Kerry's "nuanced" views on Iraq, the Bush-Cheney team hopes to persuade voters that Kerry is all over the map on all sorts of issues -- a finger-in-the-wind politician who cannot be trusted to shepherd the country though dangerous days.

Of course, Kerry sees similar opportunity in the administration's handling of Iraq. In his speech at George Washington University Wednesday, Kerry said the nation is "still bogged down in Iraq, and the administration stubbornly holds to failed, unilateral policies that drive potential, significant, important, long-standing allies away from us." The result: "a steady loss of lives and mounting cost in dollars to the American taxpayer, with no end in sight."

While polls suggest that going head-to-head with Bush on Iraq may not be in Kerry's best interest -- at least not yet -- there are collateral benefits to be gained. Democratic staff for the House Government Reform Committee released a report and database this week cataloging 237 "misleading" statements the administration has made to support the war in Iraq. If voters believe that Bush misled them about the need to go to war, they may also begin to question his honesty and trustworthiness on a broad variety of issues.

Kerry's campaign believes that the process has already begun. A senior adviser to the Kerry campaign told Salon this week that Bush's credibility with voters took a "body blow" when former U.S. weapons inspector David Kay announced in January that he had found no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Earlier this month, Kay told the Guardian that it was time for the Bush administration to "come clean" with the American people and admit that it was wrong about the threat of WMDs. Says the Kerry advisor: "I think perceptions have changed. The president used to be seen as someone who was honest and forthright, and that has changed with the WMD issue. People are beginning to see it in other areas: the deficit, having been misled about the Medicare bill. They realize that, on all these things, there has been a tremendous amount of misleading,"

The trick for Kerry is in making the mendacity stick to Bush. Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, said that Bush may benefit sometimes from the same sort of perceptions that protected Ronald Reagan: "People always assumed Reagan to be innocent by reason of stupidity, and Bush gets some of that, too," Sabato said. "People really don't think that Bush knew; they assume he simply believed what he was being told by Dick Cheney and other advisors."

Sabato thinks Bush is smarter that that. And in an odd way, it's in Kerry's interest to convince voters that Sabato's right. Recent polling shows Bush's much-vaunted reputation for honesty slipping, and that voters find Kerry -- not Bush -- the more trustworthy candidate. While Bush isn't anywhere near Nixonian levels yet, Sabato says the experience of that era may serve as a cautionary tale for this one. "In 1960, people were already calling him 'Tricky Dick,'" Sabato said. "It always caused you to think whether or not he was telling you the truth. You wouldn't accept anything he said at face value."

It will be hard for Kerry to saddle Bush with that kind of reputation, particularly since the biggest selling point of George Bush over Al Gore in 2000 was that he was a likable and honest guy. But the race is young, the campaigns are already nasty, and Kerry may just teach Bush something he missed while serving in the Texas Air National Guard: War is hell.

Shares