At 8 in the evening on Friday, a cloud of black smoke rose up from the western part of the city, drifting over the shrine of Imam Ali. This cloud hung over Najaf and we saw it miles before we arrived in town. The sun dropped through a screen of dust, but there was still light in the sky. At the amusement park, where we turned west, the black stain had grown and seemed to hang over the entire medina, but this was an illusion. The cloud came from the westernmost part of the city just before the floodplain called the Najaf sea.

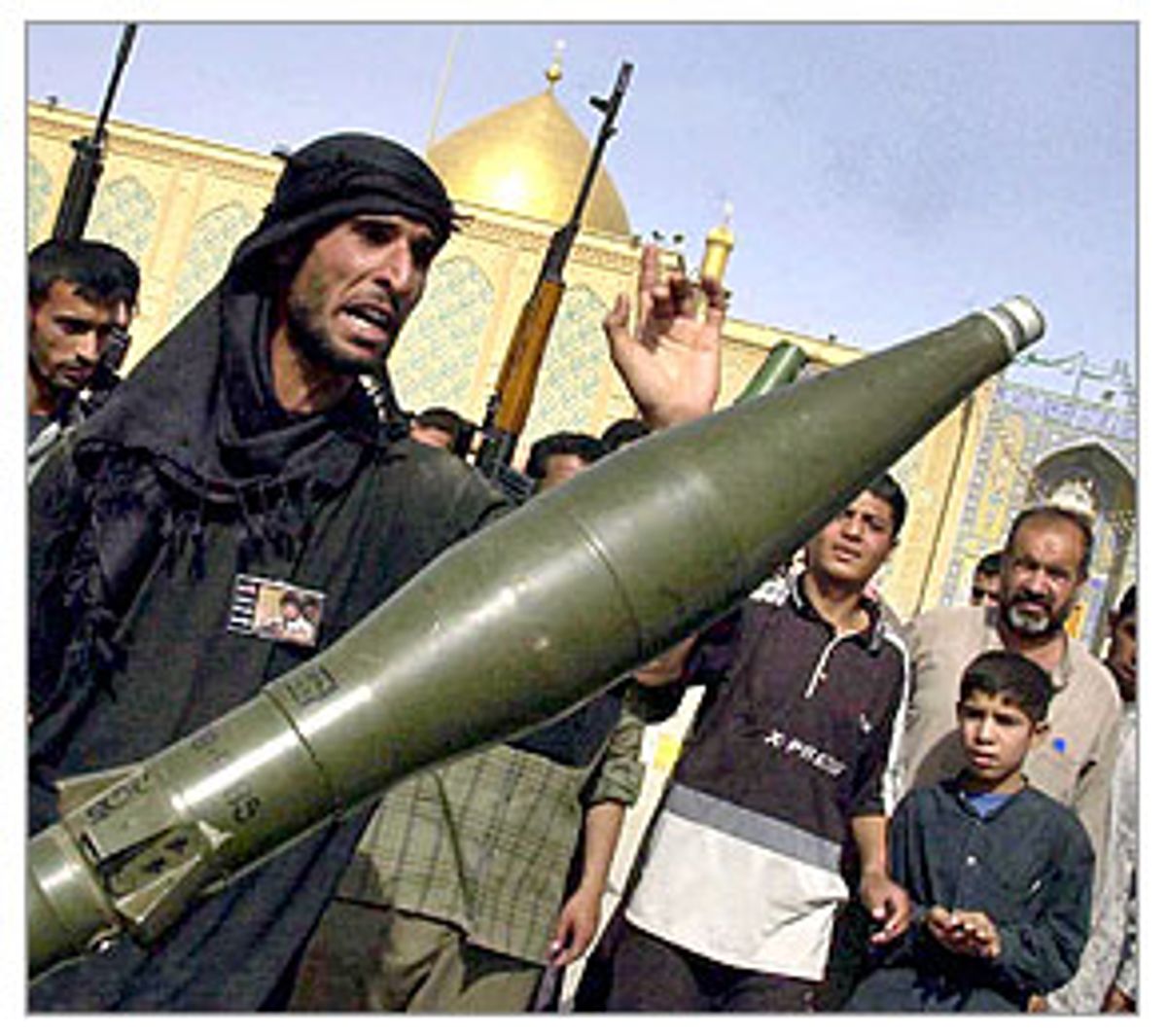

As we turned to make our approach, an old car with a blanket-covered coffin tied to the roof passed us heading away from the fighting. The cabbie tried to speak to the other driver, to ask if it was safe to proceed. One older man looked at him with a blank expression and waved us on. He had just buried a family member in the sacred soil near the shrine of Ali, and his relatives had made a desolate pilgrimage in the middle of a battle between U.S. forces and Muqtada's army. When has the West known faith of such intensity? Not for centuries. We turned to enter the cemetery from the secondary road and then we saw them: young Al-Mahdi Army fighters with rocket-propelled grenades standing near the gate, a hole in the wall where the road goes up a slight hill to the city streets. They were covered in dust and walked slowly. The fighters didn't speak.

My cabdriver, who is their age, called to them, but they did not look at his decrepit car, they looked at nothing. They were not interested in the passengers entering the holy city, which is not normal. We should have been challenged, hauled out of the taxi and interrogated, but it never happened. The fighters waved us on into the tombs and we could see that there had been explosions and fighting in the graveyard. U.S. forces came with tanks and Apaches into the place where the Al-Mahdi Army stored their weapons and laid ambushes. Four holes, each approximately 12 inches long and 8 inches wide, could be seen on the golden dome of the Imam Ali mosque, burial place of Imam Ali Ibn Abu Talib, the Prophet Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law and the Shiites' most revered saint.

You could see what happened from the rubble, but understanding came only after seeing the faces of the young fighters, the distance and emptiness. After what happened to them, they didn't care about anything. We drove into the city following a road through a million graves.

At least four Iraqis were killed and 26 wounded Friday in Najaf, and one coalition soldier was wounded, U.S. officials said. At least three militiamen also were killed, and their coffins were brought to the Shrine of Imam Ali for family and friends to pray for their souls.

"America is the enemy of God," fighters shouted.

In the past week, the U.S. has attacked Muqtada al-Sadr's militia in the three places where it is strongest: Sadr City in Baghdad, Karbala and Najaf. The old system, where the U.S. forces respected Ayatollah Sistani's advice and stayed away from the holy cities, has been abandoned in favor of a military offensive, a series of moves designed to increase the pressure on Muqtada until he gives up. U.S. forces now regularly move into positions inside the cities, fight fiercely, and then withdraw to their bases. Despite rumors of negotiations, Muqtada al-Sadr, at his regular sermon last week, urged his supporters to keep fighting. He mentioned the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

"We have now entered a second phase of the resistance, and our patience is over with coalition forces," Muqtada al-Sadr spokesman Qais al Khazali explained the strategy to Reuters. "Our policy now is to extend the state of resistance and move it to all of Iraq because of the occupiers' military escalation and crossing of all red lines in the holy cities of Karbala and Najaf."

This is what Muqtada needs most -- to lure the U.S. forces into bloody battles near the shrines, battles that are taking place now. After the holy sites are damaged by the Americans, the Al-Mahdi Army is counting on a widespread uprising of the Shia Muslims in Iraq that will push the occupiers out for good. But it might not happen that way. It appears that Ayatollah Ali Sistani and the senior Shia leaders changed their minds about keeping the U.S. away from Karbala and Najaf; they said as much in a May 4 meeting in Baghdad. What is happening now is the U.S. making a final attempt to destroy the Mahdi Army. It could mean that the revolutionary conditions Muqtada al-Sadr wanted to create have come to pass. But it could also represent a bitter end to a gestating Islamic state, not a glorious beginning. Muqtada's support in Najaf is crumbling, the pilgrim economy shattered by constant fighting. Respected Shia religious figures here have called on him to leave the city. Karbala, where his support was never that strong, wants the fighting to stop.

On Saturday night in Baghdad, just after U.S. forces arrested two senior Al-Mahdi Army leaders. I spoke to a 24-year-old Al-Mahdi Army official, Saeed Hisham al Mousawi, who said that the Shia Islamic parties brokered a sell-out deal with the coalition. "After the Islamic parties met, the U.S. forces closed all negotiations. I am sure that some parties gave the U.S. the green light to attack." Al Mousawi meant that the U.S. got the green light to destroy the Al-Mahdi Army at their meeting in Baghdad on May 4. The young revolutionary, who is still living with his parents, was bitter about the betrayal. I wanted to know which party had betrayed them and he wouldn't come out and say the name. But it seemed clear that it was the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq, which is close to Ayatollah Sistani. The next day the U.S. destroyed the al-Sadr heaquarters in Sadr City, attacking with tanks in another fierce battle. In 24 hours, the al-Sadr headquarters was completely rebuilt.

"They could come and destroy this place a million times, and I will rebuild it a million times," Sheikh Mustapha al Askari said on Monday, and he grinned at me in an ecstatic way. His hands were covered in plaster dust from building a wall. "The al-Sadr office is in my heart, it is not here." Fifty young volunteers working on the building shouted their agreement. But Muqtada has forgotten to appease the old men, and the old men were turning against him.

Lately the fighting has evolved from small clashes at the edge of towns to long firefights in the center of cities, and it took no time at all. This is the aftermath of the understanding between the U.S. and the Shia figures, their bid to destroy the Al-Mahdi Army. It suddenly became impossible to chase the wire reports; we didn't know where to go, so we drove from one city to the next, from Sadr City to Karbala and now to Najaf. By early Wednesday morning, the U.S. had destroyed the al Mukhayam, an al-Sadr mosque in Karbala, and was busy fighting Al-Mahdi Army soldiers 200 meters from the shrine of Imam Hussein. In the afternoon when I arrived in the city, it was still going on. A group of young boys near a checkpoint had video cameras and showed their own footage of the attack on the al-Sadr mosque. They were intensely proud of what they had captured.

On the small camera display, a cityscape brightened and faded with the explosions of missiles from Apaches. One thin boy said, "Whenever I go to take pictures of the Americans, they shoot at me." The boy was still shaking when he said it, because he had just been down the road where the tanks were waiting. It took a second to realize that the boys weren't in any militia, al-Sadr's or anyone else's, they were out watching the firefight because they were curious. It would have been interesting to stay with them, but Abu Hussein was nervous and wanted to move our car.

We drove past the shrine toward the al Mukhayam until we couldn't move because of the shooting along the street the alley opened into. Abu Hussein felt pinned by the small streets; he kept talking about the car and keeping the car safe and he wanted to leave Karbala immediately. In the medina, we heard the deep sounds of the U.S. weapons and the small arms of the Al-Mahdi fighters reflected off the houses. I went up on foot to see where the shooting was coming from and ran into an angry mob. Abu Hussein pulled the car around the corner, and once we were out of the first alley he met an old friend, a pharmacist who was visiting his uncle who lives nearby. We talked on the street corner as the fighting went on in the medina. Alla Mohammed was incredibly reasonable as the world came apart around him. "You can talk to him, he speaks English, " Abu Hussein said. We spoke English.

I wanted to know why, if there was so much fighting going on in Karbala, there wasn't a flood of refugees. "Nobody is leaving, where can we go?" Alla Mohammed said. "In 1991 we left and Saddam bombed the entire city." Above all, Alla Mohammed believed in peace; he wanted the fighting to stop so his children could go back to their exams. "We want to work with the Americans, we just don't know what they want exactly. We are suffering and want something good for our future, but do you see any development in a year of occupation?" I agreed that there wasn't much to see. "My economic situation is good, but if I had to feed my family and I was unemployed, for a hundred dollars, I would fight," he said. We had to stop talking because Alla Mohammed wanted to evacuate his uncle's family from the medina. So they piled into our car, three women in their abayas and a 4-year-old girl sitting in the middle between them. Alla Mohammed's uncle didn't come with us, he stayed with the house to protect it from looters. As we turned the corner he waved at us in a cheerful way. If he was sick with dread, he didn't show it.

"The house is much safer from the looters if it's close to the fighting. The thieves won't go near it," the pharmacist said. Iraqis have a particular disdain for thieves and looters because there are so many of them. Alla Mohammed and his extended family got out of the yellow Caprice and disappeared into his house, a bit farther from the fighting.

Abu Hussein's family is from Karbala, so we went to visit them on the outskirts of town. Like Alla Mohammed's family they were huddled inside the house and had been for 48 hours. No one had slept at his father's house either. All the brothers had come from their houses with their families, and they were cheerful given the circumstances. All the men ate fruit and smoked cigarettes in the guest room. It was in Abu Hussein's house that I learned that his brothers do not idolize the Mahdi Army like he does; they are Sistani people, and they look down on Muqtada. As we talked about the situation, Abu Hussein got angry and said that the sounds of shooting we heard in the medina were tape recordings, which made me think he was losing his mind. There was no choice but to come back to Baghdad.

On Friday, two directionless days later, Najaf exploded and became the next destination. In the Badr hotel, a place that I cannot leave for the time being, there is a small generator running and the steady drone is interrupted by the outside world. Now, at 2:50 in the morning, there are detonations from tank shells and bursts of small arms fire to the east. If this is supposed to be the decisive U.S. offensive against the Al-Mahdi Army, it isn't over yet. I thought of what Alla Mohammed said to me on the street corner in Karbala. "I don't think it will end now."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Shares