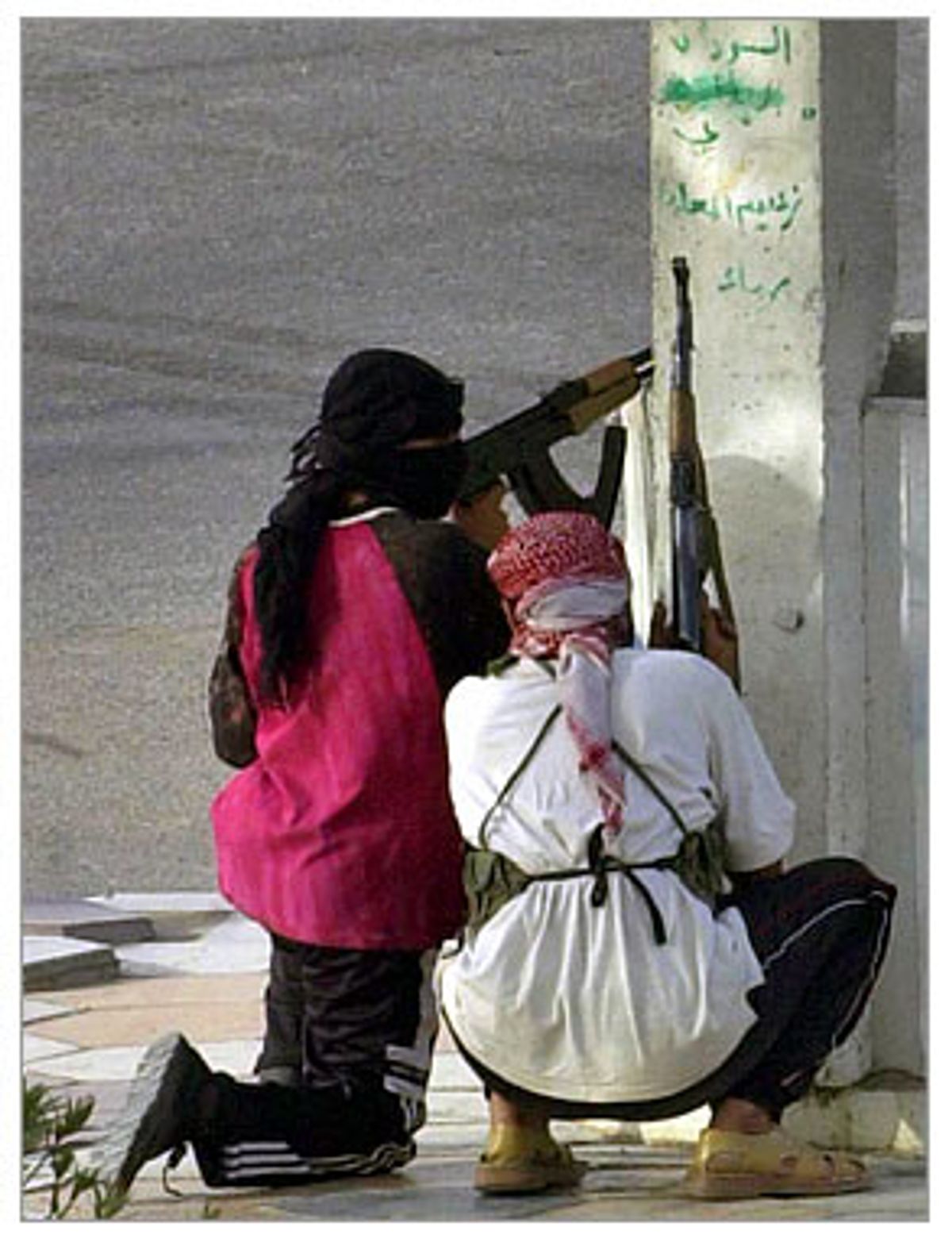

On Friday afternoon, shortly after Muqtada al-Sadr gave a Kufa sermon that sounded like a goodbye message, Iraqis were running down the main street near the Tho al Fikar hotel. They were running because an intense firefight had broken out between U.S. forces and the al Mahdi Army. Or at least that is what started it. Al Mahdi snipers had taken their places on the tops of the hotels so they could get a good shot at the Americans and they were shooting east, toward the police station. Then fighters came inside the hotel and told journalists that if they went up to the roof they would be killed. Everybody ignored them. The snipers fired all afternoon and part of the evening, and from the roof of the Tho al Fikar, we saw a gas station throwing out a long skein of smoke into the sky.

In his Kufa sermon Muqtada had told his followers that they should fight on even if he was killed or captured, and the young leader took the time to thank various organizations, like the Sunni cleric's association, for their support. When I heard about the speech from a journalist who'd been there, it sounded like a retirement address, or a goodbye. Muqtada al-Sadr is getting ready. His photograph in Ansar al Mahdi, one of his official papers, shows an assistant dressing him in martyr's white, while the headline reads, "The Eagle of Benihashim Prepares to Die." The Benihashim are the descendants of the prophet Mohammed.

Just as the sermon was starting in Kufa, I walked down the long street that separates the Najaf medina from the new city until it hit a ramshackle market. I had been trying to get to al-Sadr's sermon, but it was impossible to drive to Kufa because a battle had started at the edge of town and the road was closed. Under a patchwork of orange tarps and ragged sheets, swarms of flies lit on rickety butcher counters, some still wet with blood. Friday is the traditional day that sheep are slaughtered in Iraq and the market had been full a few hours earlier. A moment later, a young al Mahdi fighter approached Mustapha, the translator, and insisted that it was forbidden to go any farther without permission. So we took a detour through the reeking market and listened to the sound of firing from an American gun, interspersed with rocket-propelled grenades. We ignored the al Mahdi fighter's instructions and headed toward the al Fikar, which was much closer to the fighting. Close to the market, we saw men huddled under the sheets in deep conversation. We were greeted politely, which is something of a miracle under the circumstances.

The city is gradually slipping into chaos; the fighting is longer and less predictable than it was two weeks ago. Najaf is polarized between two groups, one violent and one that advocates peace. I returned to try and understand the relationship between these two groups of Najafis and what had changed in the last month. Ayatollah Ali al Sistani, the most respected Shiite religious figure in Iraq, lives in a modest house near the Shrine of Ali. The house is on an alley just off Rasul Street, one of the rambling walking streets that lead to the gold-domed shrine at the center of the city. It is also off limits to visitors. At the entrance to the narrow alley, five dour men with rifles were waiting for Sistani's house to be attacked by the gunmen from the al Mahdi Army. Directly across the Rasul Street entrance to Sistani's alley, there is an al Mahdi Army checkpoint and the young fighters who were searching pedestrians on their way to the main square were only a few feet from the men who guard Sistani. They were busy pretending to ignore one another.

In the past week, fighters of the al Mahdi Army shot at Sistani's house several times in an obvious effort to scare him into keeping quiet. It's a desperate move. Other clerics in Najaf got the same treatment. Sheik Ali Najafi said that his father had received threats all the time, either unsigned notes or bullets. Everyone knows who is doing it. The Muqtada people don't appreciate what the clerics are saying about them. Recently, Ayatollah Ali al Sistani, who is originally from Iran, called for the al Mahdi Army to leave Najaf along with the American forces and take their fight elsewhere. It was a dangerous thing to ask Muqtada to do. If he withdraws from Najaf, the al Mahdi Army is finished. Muqtada al-Sadr, who has said in the past that he will obey all orders from the religious authorities, simply refused to go when the order came down.

Sistani and Sadr, through spokesmen and armed supporters, are now in a kind of low-level war. But by shooting at Sistani's house as well as the offices of other senior clerics in Najaf, Muqtada has lost most of the support he had in civilian Najaf, leaving only the armed boys and the younger clerics backing him. The city has seen the religious pilgrims, its major source of income, scared away and the citizens who depend on them are getting angry. In a town where religious life and daily life are identical, attacks on respected clerics amount to nothing less than crimes against Islam. Muqtada al-Sadr's father, Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr, was killed by Saddam Hussein in 1998, and following his death the Shiite community in Iraq convulsed. There will certainly be more violence if Muqtada dies at the hands of the Americans, but he is not a marjah -- a religious elder -- and does not command the respect his father did. Muqtada al-Sadr cannot issue fatwas, for example. His wake will be violent for different reasons, and everyone in Najaf is waiting for the hammer to fall.

On Wednesday afternoon, a few feet from the Sistani checkpoint, a middle-aged Iraqi man was walking to his small bookstore. Al Mahdi Army fighters have made a point of threatening his life, so it is better to just call him Ali. Ali was tired; there were dark circles under his eyes, which I noticed when he rolled his glass display case toward the sidewalk. He was opening up shop and rolled the display case out on small ingenious rails of his own design. Ali built them so the store could be folded up and put away when business was done. It reminded me how many Najafis had learned in the past few months to retreat from the fighting without leaving town. They had adopted a lower profile, pulled the doors closed and disappeared. Ali, the notable exception, was opening his shop while everyone else was closing theirs. He is living in fear for his life and he is not sleeping well. Things are breaking down.

"The Al Mahdi Army are all barbarians, they are mindless, they can kill anyone and no one will say anything," Ali explained under shelves full of dusty Islamic volumes. He took me back to the Internet cafe and pulled up a digital snapshot of the newspaper Ansar al Mahdi, and it showed a man in Iraqi clothes who had been hung, the rope still around his neck, the head forced into an unnatural angle. He craned his neck toward the ceiling. The man's body was slumped in a chair. The executed man was holding a large yellow placard that described him as a collaborator. "They are proud of it, look, they published it themselves," Ali said in disgust when he brought up the image. He told me that they had probably executed people suspected of spying in the Islamic court a few blocks away. The picture looked authentic; the paper was dated the 28th of April. "Najaf is dying," Ali said.

I asked Ali if he was getting threats from the al Mahdi Army. He nodded. It happened all the time. Ali said a Muqtada gunman recently told him, "We know you are a spy for the Americans. You are worth $10,000 if we kill you." This threat was one of many they had made against the bookseller. That is their style. The al Mahdi fighters think everyone is a spy who is not part of their organization, and now that people are turning against them there is a certain amount of truth to it. They are suspicious of foreign journalists, but they are far more worried about the people of Najaf. After my conversation with Ali, it was easy to see why. Ali hates the al Mahdi people in a visceral way and walks down Rasul Street with his haunted look without trying to hide from the packs of armed men.

When Ali brought out the cold soft drinks, he came out and said that the al Mahdi Army was receiving new shipments of weapons from outside Najaf -- he thought from Iran. I asked him how he knew about the guns. "I saw them unpacking crates of rifles near the Sadr office," Ali told me. "The roads are open, anyone can bring them in." I have heard the story about the weapons shipments many times in the last few days, but it's hard to track down the details. A number of observant people are certain that arms are coming in, but they aren't sure where they are coming from. It is also true that there are unfamiliar, new-looking rifles held by some of the checkpoint soldiers. These weapons are much better than the old Kalashnikovs which are everywhere in Najaf.

Before leaving, Ali gave me an important tip. He told me that the sheiks were convening a meeting to demand that Muqtada leave Najaf. The meeting would take place the next morning, out in the country, at a place called Misha'ab. Muqtada's support was about to take another blow.

On Thursday in Misha'ab, a farming village near the Euphrates River, sheiks from large and small tribes filtered into the large hall in the mosque. There is a throne at one end of the long room and the congregation of men wore the black cord over the black checked kaffiyehs. All wore their white dishdashas and thin woolen abays, a tribal symbol of rank. One old sheik sat with great dignity, holding a walking stick made from a piece of rebar. Another man brought coffee in small cups and was careful to offer a drink to every one of the several hundred men who were waiting for sheik Haider al Fatlawi to make a statement. Fans on long poles stirred the air in the room. The sheiks, who are famous for shifting allegiances, chatted with one another and seemed to be in a good mood. They weren't there to negotiate; they had come in an act of solidarity, and to send a message to the al Mahdi Army and Muqtada al-Sadr. After several hours, al Fatlawi appeared and called for the militias to leave Najaf and Karbala, which was expected, since Sistani has said it several times before.

Al Fatlawi is not only the highest-ranking tribal leader in the area, but also an important advisor to Sistani. It seemed that Sistani had called the meeting, and the sheiks had responded with their support. In the tribal meeting hall, the Husseiniya, Al Fatlawi, handed out a printed statement, made a few restrained comments for the cameras and then vanished. We expected a speech but didn't get one. The printed statement, which repeated all the familiar requests that Sistani had put to Muqtada, ended by saying that attacks on the religious elders would not be tolerated. Tribal authorities and police should take control of Karbala and Najaf as well as guard the marjahs. All other military forces should leave. Sistani's office had also countered Muqtada's request for help from fighters outside Najaf, saying that they shouldn't come, that they weren't welcome in the city. It was a problem only for Najafis to solve.

After al Fatlawi handed out the sheet of paper, the sheiks filed slowly out of the hall and assembled on Misha'ab's main street for a demonstration. They walked under the burning sun, chanting that they would defend their religion. It was a rhythmic song like Muqtada's but with none of the anguish and requests for divine intervention. Their voices weren't raw like the fighters'. Around them, thin men from the tribes, armed with Kalashnikovs, guarded the demonstration. A pickup truck of Iraqi police went down the main street. Out in the country, they were safe from attack by the al Mahdi Army and they seemed relieved to be doing a useful job without the threat of assassination.

Back in Najaf that afternoon, I tried to visit Sistani's house to see how it had been attacked by the gunmen, but the dour men at the Sistani checkpoint were not interested in showing the bullet marks to journalists. They were following instructions to keep the press away from the marjah. If I wanted to speak to a representative, I was supposed walk down Rasul Street to the Sistani office. At the home of another cleric, I was told to prepare questions in advance and never bring up politics. "The community of elders is above politics and will not speak about them," the representative explained. But politics in its most explosive form was all around us.

The war between the al Mahdi Army and the coalition forces has created an environment of merciless self-censorship among the clerics. Sheik Ali Najafi said at one point in the interview, "Please ask your question in a more indirect way." But it was ridiculous to formulate it in an indirect way. I wanted to know what kind of threats they were getting from the al Mahdi Army. What sort of pressure were they under? If we couldn't talk about what was happening, there was nothing to talk about. Just as our talk ended, a fighter fired a rocket-propelled grenade nearby and it made the characteristic kettle-drum sound when it detonated. Still, we were not allowed to talk about it.

At the Sistani office, where I expected to have to prepare questions in advance and promise not to ask about current events, I met the editor of Holy Najaf, a Sistani-run magazine. He was young and willing to talk. Saeed Raith Shabbar, a slight, handsome man in a black turban, admitted that someone shot at the roof of Sistani's house but couldn't say anything else. He didn't want to further inflame the situation. "We hope that the American government respectfully takes the advice of Saeed Ali Sistani to leave Najaf. If they do it, they will prove to the world that they are civilized. If there is damage to the shrine, it will be the responsibility of the groups who are fighting," Shabbar said. He knew that neither force would withdraw from the city because Sistani and the other marjahs requested it. "If someone does not obey your request, you cannot give him an order," he observed and shrugged.

I asked him if he wanted to say anything else and he made this observation: "When I watch the news from all over the world, I feel that we have returned to the Stone Age. The people fighting cannot stop and return to peace." This observation had been on his mind and he wanted to make sure the translation was correct. "All of humanity is suffering right now because of fanatics." This is exactly what he wanted to say and he had written it down to make sure we got it right. For Shabbar, Bush and Muqtada were manifestations of the same fault in human nature, the mysterious blown fuse that leads people to destruction. We considered what it took to make such a person, the banishment of doubt, the ugliness of absolute belief without reason. Najaf and Karbala were two places where the fanatics of the world were duking it out, a small stage that represented the greater world.

"When they pick up a gun, they become monsters," Shabbar said when I was leaving. He made the intensifying war in Najaf simple by showing that it was ultimately pointless. I was sorry to go. As I walked out the door with my translator Mustapha, the al Mahdi fighters watched us carefully. On Friday, when I came back through the al Mahdi checkpoint, they said to me, "We know you're against us."

From the roof of the al Rasul hotel at 11 o'clock that night, we watched the U.S. and the al Mahdi fighters engage in a two-hour battle. There was a long line of bright flashes that stretched from the western boundary of the city near the Najaf sea all the way to 1920 square on the east side, an electrical storm brought to the earth. There were flashes and detonations from the direction of Kufa. Red tracers floated up in perfect arcs while al Mahdi snipers fired away, sometimes at nearby buildings. Someone was shooting at the al Mahdi fighters inside the city, but we couldn't see it and it was difficult to move down the dark streets.

From the roof of the al Rasul, we knew that most of the battle took place at the northern edge of the vast graveyard for the shrine, but there were shots from other places in the city as well. American machine guns have a deep, froglike sound that Russian weapons do not, so it is easy to know where the Americans are. We also know that the shots we heard were not only directed at the Americans because there are also sounds of Iraqi weapons firing and answering. This means that other, hidden battles are taking place in Najaf; armed forces are attacking the al Mahdi fighters from rooftops and cars, anti-Muqtada men moving through Najaf looking for easy targets.

Two new men have moved into the al Rasul tonight. They have come from Basra and they are volunteers for Muqtada's militia. They are here because they responded to his appeal for help. The two men did not come with their guns -- they will pick up their weapons tomorrow after the al Mahdi officials give them their IDs.

After visiting the shrine and praying, they went out for a bite to eat. The two men didn't stay out late, because tomorrow will be a long day.

Shares