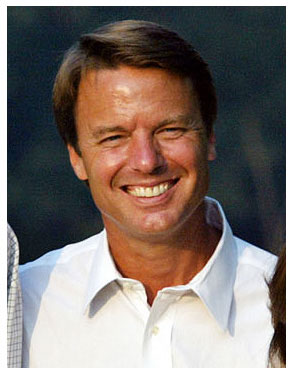

John Edwards carries his log cabin with him. The son of a millworker in Robbins, N.C., he bears the memory of his family going to a local restaurant after Sunday church, only to leave when his father realized they could not afford the prices on the menu. It was hardly a contradiction that he became a plaintiff’s attorney winning multimillion-dollar decrees against large corporations and becoming wealthy himself, and a U.S. senator, without ever holding a lower office. His unbridled ambition was further apparent in the first-term senator’s run for the presidency; his theme of “two Americas” was affirmed, not belied, by his biography, lending him the fervently sought but ineffable political quality of authenticity. By his turns of phrase and obvious pleasure in the arena, he was effortlessly able to make his populist message seem buoyant. In his short career the misimpression that he is a Bambi, a “Breck girl,” ridiculed by his opponents for his full mop of hair, has only enabled him to become the fair-haired boy, the favorite Beatle.

Edwards might well have been the Democratic standard-bearer if John Kerry hadn’t early locked in the most seasoned operatives in the Iowa caucuses; as it was, Edwards finished second. The Democrats decided to avoid their characteristic factional warfare and to support the figure they believed could win. It was no judgment against Edwards, whose campaign was indefatigable, appealing in small towns and rural areas that had fallen off the map for Democrats, and he was utterly lacking in bitterness when he was defeated. At the big Democratic dinner in March, where former Presidents Clinton and Carter anointed Kerry, Edwards raced to center stage to lift his arms alongside the next nominee — as public an announcement as he could make that he was campaigning for running mate.

When Kerry chose Edwards their complementary natures were obvious, down to Edwards’ succinctness. By virtue of having Edwards, Kerry also acquired his “two Americas” theme as one of his own. But that simply suggests the larger consequences of Edwards.

Just as Edwards underscores the endurance of the Southern Democratic tradition, so does he underscore the dead end of conservatism in the person of Dick Cheney. The thread of the Southern Democratic tradition that now runs through Edwards opposes the one represented by President Bush and Vice President Cheney. These Southern politics have been in conflict since President Andrew Jackson split with his vice president, the original theoretician of Southern reaction, John Calhoun. The Jacksonian slogan was “opportunity for all, special privilege for none.” But the Calhoun wing of the party triumphed, leading to the Civil War, eventually the end of Reconstruction, and the long rule of the Bourbons, or local oligarchs, who maintained their power under the rubric of states’ rights against federal authority. African-Americans were disenfranchised under Jim Crow, and poor whites, sharecroppers and mill hands like Edwards’ father and grandfather were manipulated by racial fears and a hatred of intruding Yankees like Kerry’s ancestors.

The Bourbon Democratic Party of the South came to an end with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Republicans, no longer the party of Abraham Lincoln, absorbed the new conservatism that followed, converting the once solid Democratic South into the solid Republican South. But the Republican project was never as stable as it seemed. In 1976, Jimmy Carter carried most of the South, and twice Bill Clinton broke off important states and moved them into the Democratic column. Now this mantle, worn by Clinton and Carter, and before them Lyndon Johnson and Harry Truman, falls on the shoulders of Edwards.

Bush’s strategy is a supra-Southern strategy involving the exploitation of patriotism, resentment and fear. The threat, real enough, is external, and it is brandished to maintain the status quo. His compassionate conservatism is an updating of planter paternalism. But his agenda is deregulation, low taxes and hydrocarbons. His politics in the South fundamentally rests on a division between godless them and God-fearing us. Beneath that, he requires a nearly unanimous white vote to compensate for the Democrats’ nearly unanimous African-American vote. If more than one-quarter to one-third of the white vote goes into the Democratic coalition, depending on the state, the Republicans lose.

The solid Republican South must have a solid white vote in every Southern and border state without exception to maintain a Republican in the White House. A crack anywhere topples the entire edifice. That fragility accounts for the ferocious struggle in Florida.

The instant Kerry announced Edwards, the Republicans opened an attack on him as a trial lawyer, supposedly the mark against him. Yet in 1998, when Edwards first ran for the Senate in North Carolina, his Republican opponent, a tool of the Jesse Helms political machine named Lauch Faircloth, spent $2 million on advertising depicting Edwards and hate-figure Clinton with Pinocchio noses as “two tobacco-taxing liberal lawyers who are well known for stretching the truth.” The ads backfired; Edwards won handily.

In one of his prominent cases, involving a girl left brain-damaged by hospital neglect, Edwards told the jury: “She speaks to you. But now she speaks to you not through a fetal heart monitor strip; she speaks to you through me.” The tradition for which Edwards now takes his stand is as open to demagogues as to statesmen, but in the mouth of a statesman it can undo a demagogue.