For a sex farce to be any good, it has to risk offending somebody. And since there are a lot of people who can't loosen up enough to laugh at the idea that what turns us on may upset our most deeply held notions of who we are, it's often not hard to offend people.

With "She Hate Me" (lousy title) Spike Lee, who co-wrote the movie with Michael Genet, has a good, potentially inflammatory comic idea. John (Anthony Mackie) is a successful young black executive who loses his job and makes ends meet by becoming a stud to prosperous lesbians who want to get pregnant -- at $10,000 a pop. He gets started when Fatima (the luminous Kerry Washington, who deserves better), the ex-fiancée John found in bed with another woman, turns up at his apartment wanting to get both herself and her lover, Alex (Dania Ramirez), pregnant, and offers to pay John for his services. Sensing a great business opportunity, Fatima becomes John's pimp, trumpeting his abilities to her "glam dyke" friends and taking a 10 percent cut. Soon the Sapphic elite are lining up at John's plush apartment and leaving happily, as the Brits say, up the spout.

The problem with "She Hate Me" is that there's no playfulness in Lee's provocations. He doesn't have the style or the naughty joie de vivre that you need to make a sex farce. The idea of directing with a glancing touch is alien to him. He wants to score points -- and if he has to slug you to do it, he will. Lee seemed to be moving beyond that in his last picture, "25th Hour," a near-great American movie. In "She Hate Me," he's back to his ham-fisted, insensitive style. I don't agree with the advance reviews that have labeled the movie homophobic, but it's easy to see why some critics have misread "She Hate Me" as saying that all lesbians, no matter what they claim, are really hungry for dick.

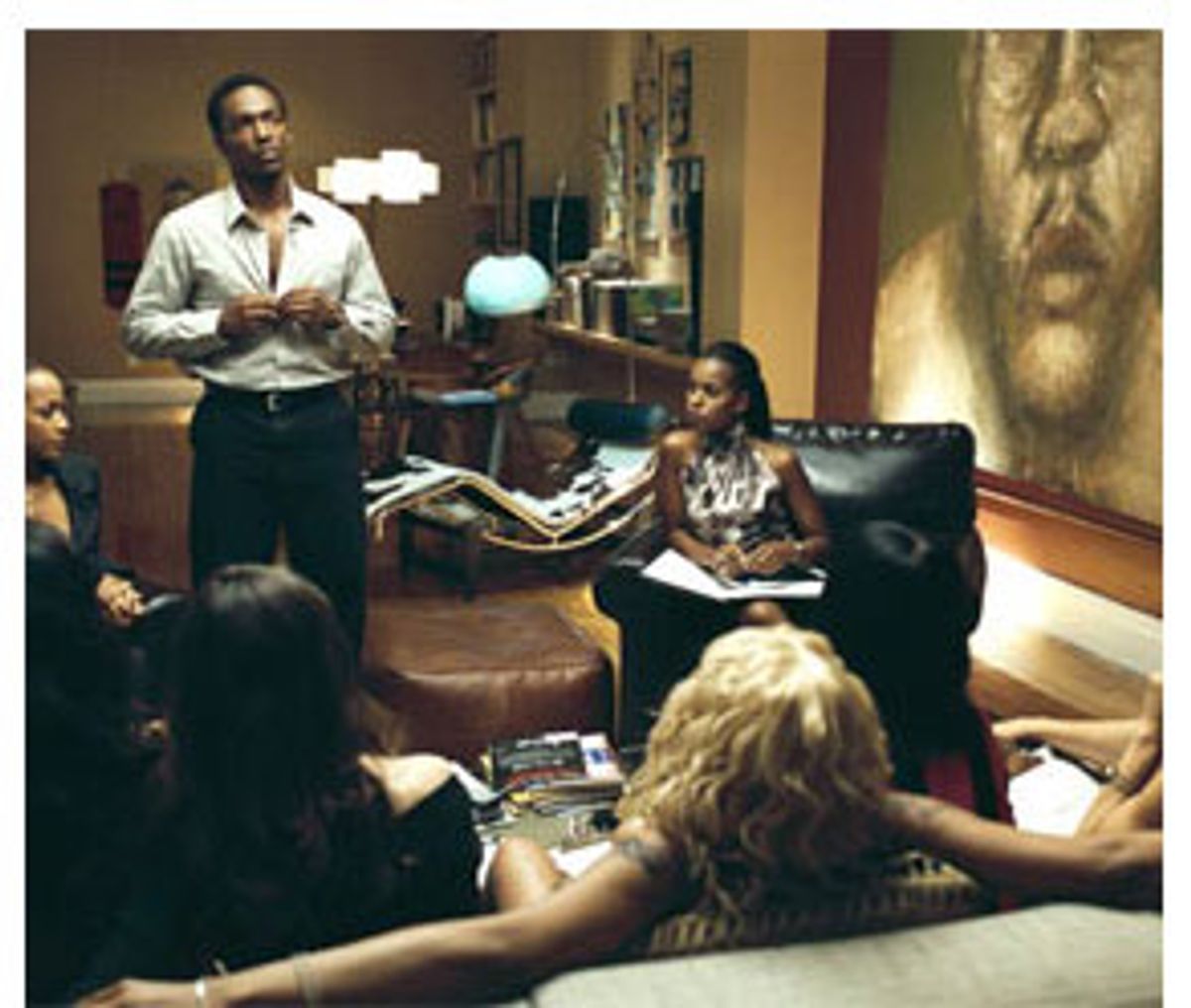

Certainly, Lee does what he can to make lesbians appear predatory. When Fatima and Alex first turn up at John's digs, they fondle and leer at each other on his expensive sofa as if they were prepping for a scene in one of Andrew Blake's designer pornos. When Alex brings her first batch of prospective customers over to John's apartment, they check him out like the crass, boorish young execs you sometimes see at strip clubs. This role reversal isn't played for laughs (the way it is when women leer at a solitary man on the subway in Bertrand Blier's "Femmes Fatales"). You feel that Spike Lee resents seeing a man in a position usually reserved for women.

It should be funny when John's customers are happily bouncing their way toward orgasm and mommyhood, but Lee directs the scenes as if the women's sexual happiness were a foregone conclusion. Lee doesn't allow them to show surprise at their pleasure because he's not surprised by it. (It doesn't help that Terence Blanchard's make-out mood music is slathered over the soundtrack.) And showing John popping Viagra and quaffing Red Bull to service the four of five women Fatima brings him each night reinforces the image of the evil lesbos draining the man of his juices.

But midway through, there's a scene between Mackie and Washington that suggests a smarter movie than the one we've been watching. John, who has never gotten over finding Fatima in bed with that woman, spews his resentment at her for not telling him she was gay. Fatima talks of how she denied her sexuality to herself for years and how she had to find out before she married him. It's one of those irresolvable arguments nursed by years of wounded pride and resentment. John rails against black men on the down low and against the idea of a gay gene. Fatima calls him a homophobe.

What's striking about the scene is that it's directed to be far more sympathetic to Fatima than to John. John, who we've assumed to be speaking for Lee, is presented as a man who can't bring himself to understand the very concept of being gay. The key to the exchange, and I think the thing that has upset some critics about "She Hate Me" more than the plot, is the moment when Fatima tells John that she can't define herself as gay or straight or bisexual solely for the purpose of making him comfortable, that she rejects putting herself into narrow categories.

If you're paying attention to the undercurrents of the scene, or to the undercurrents in the debates over sexual identity, that line can make you gasp.

Somewhere along the way, the idea that sexual identity can be mutable stopped seeming a reasonable assumption of those who favored sexual freedom and started being treated as a tool of those who want to limit sexual freedom. We've all heard the right-wing and the religious right trumpet stories about "reformed" homosexuals as a way of bolstering the notion that if you choose to be gay, you can choose to be straight. And it's easy to see why gay men and lesbians who have built their identity on their sexuality are so opposed to the idea of sexual preference -- as opposed to sexual orientation.

The problem is that those arguments, useful as political tools in arguing for or against gay rights, have next to no value in art, which, at its best, seeks to explore the mystery of human behavior rather than shut it down. (And even politically or socially speaking, insisting that sexual identity -- or sexual relations -- must be fixed and immutable, no matter what ideology that's coming from, is an intrinsically repressive notion.)

As "She Hate Me" goes on, the characters of Fatima and Alex become fuller, more human -- not because becoming pregnant changes them and makes them more like "women" but because, the movie suggests, John is finally able to see them as human beings. The critics who have argued that the end of the film says that lesbians will always feel incomplete without a man and will sacrifice their independence to have one in their lives are naively expecting fictional characters to act in ways that fall within their own political comfort zone. (Similar nonsense was at work in the reviews of Mike Hodges' "I'll Sleep When I'm Dead," the story of a London gangster who goes after the man who raped his brother. Critics derided the hero's quest to redeem his brother's masculinity as homophobic -- as if a macho London gangster should be expected to share the values of liberal critics, some of whom talked as if rejecting male-on-male rape were the same as rejecting gay sex.)

I have to admit to being moved by the end of "She Hate Me," which has the grace to allow for the possibility of change and growth in its characters and which suggests that human behavior is not always predictable and that life makes nonsense of exactly what it is we think we know. This is the section of the film most in tune with the inclusiveness that marked "25th Hour." But to get to it you have to wade through nearly two hours and 20 minutes of Lee fomenting divisiveness. And if critics aren't recognizing the contingencies and ambiguities of the end of "She Hate Me," it's because they've been paying attention all too well to what comes before.

Lee does damn near everything to cripple any sense of nuance. He has John spend most of the last scenes apologizing for his irresponsible behavior -- as if a man providing sexual services to adult, financially independent women who have paid for it is the same thing as a man indiscriminately impregnating any woman he can get into bed. He makes John out to be such a stud that one of his clients (Monica Bellucci) even feels the moment his sperm fertilizes her egg. He has John's ball-busting boss (Ellen Barkin) talk about how much she loved being pregnant, even the morning sickness.

Lee isn't a precise or disciplined enough artist to pull off the tone shift that would define the change in the way John views Fatima and Alex. He's content to let the audience laugh at John's perception of them as predatory dykes, and so he seems to be milking black homophobia as much as castigating it. Though Lee is finally compassionate toward Fatima and Alex, he's got too much macho in him for me to believe he'd be capable of showing as much compassion to gay black men.

And instead of John's losing his job being a mere pretext for the plot, Lee turns it into his comment on corporate corruption in the era of Enron and WorldCom. John blows the whistle on the dirty goings-on at his company and finds that he's suspected of wrongdoing by the SEC. His company somehow (it's never clear) gets the government to freeze his assets, and the organization's slimy chairman (Woody Harrelson) puts out the word that John is untrustworthy and can't be hired.

This is the preachy side of Lee -- and the kind that liberal audiences tend to swallow because they believe what he's saying without questioning the plausibility of what he's showing us. So the existence of corporate racism is used to justify the scene where Harrelson trumpets his hiring of people from the "darker nation." Does anyone believe an exec facing scrutiny from the SEC would risk talking like that? For that moment -- or a scene purporting to be a reelection ad for Bush -- to work, the tone of "She Hate Me" would have to be more wildly satirical than it is. But Lee, who always has an agenda, is fundamentally unsuited to satire, which has no sides, no friends, no agenda.

At times, "She Hate Me" feels like the clumsiest, most amateurish movie ever made by an acclaimed director. Matthew Libatique's cinematography looks almost purposefully ugly (especially the green-gray tones of the office scenes), the editing is rhythmless, the characters talk in topic sentences rather than to each other, and the repeated animated sequences of sperm bearing John's face are cheap looking and unfunny.

I wish I could say that the leaden, soapbox ranting of "She Hate Me" -- much of it delivered by actors staring right into the camera -- will put audiences off. But if "She Hate Me" comes a cropper at the box office, it won't be because of that. Along with "Fahrenheit 9/11" and Jonathan Demme's new remake of "The Manchurian Candidate," "She Hate Me" is part of the current group of political films that assume the audience is so stupid it has to be yelled at. Essentially, Michael Moore, Demme and Lee are no different from Ellen Barkin's scheming corporate exec, who says that the American people are so "fucking stupid" they'll believe what they're told.

There's a particularly depressing moment in Demme's slack, witless "Manchurian Candidate" when we see a newspaper headline that reads "Muslim Student Beaten to Death at Yale." Think about that. If Demme's point is that he fears for the safety of Muslims in America right now, then why not just "Muslim Student Beaten to Death"? The answer, I fear, is that Demme is implying this type of thing is what you'd expect in the Yahoo States of America under George W. Bush -- but if it happens at Yale, things must really be bad. It's an elitism I would never have expected of the man who made "Melvin and Howard" and "Something Wild." And it's an elitism that, in the political desperation people are feeling at the moment, seems to have become perfectly acceptable in the arts.

For a few years now, political pundits have been talking about how we can't gut our civil liberties in order to beat the terrorists. There's another danger afoot. It's time for critics to start speaking up against gutting our notions of good art in order to beat Bush.

Shares