I want to be Jeremy Wariner! I saw him smoke the competition in the 400 semis on Saturday night, and the dude was so cool with his mini-goat and his shades and long thoroughbred body and his impassive face, and mainly he was so damn fast, that I kept checking him out with the binoculars to see if he really was white. I know, we're not supposed to notice this, and if we do we're certainly not supposed to say anything, but ... come on. As a mongrel racial type myself who could shut down just about everybody of any color in my high school over 60 yards, I never had any truck with the idea that it's somehow indecorous or objectionable to notice that race matters in sports. The subject is so loaded in a bad way most of the time, it's nice to have a few subjects that you can just drop on the table with an innocent, loud thud.

According to the dictates of racial politeness -- as witnessed by this thread from a runner's forum -- pulling for a member of one racial group, particularly if it's your own, is evidence of racism. That may sometimes be true, but it doesn't have to be. Race isn't a zero-sum game, and the best way to restore some innocence and sanity to it is to allow there to be some places where you don't have to take it so damn seriously. So I'm all for bringing back the Great White Hope. Let a thousand pale-skinned, non-possession wide receivers blossom! You don't pull for Jeremy Wariner because you want to tear down Michael Johnson: You hope that the white kid can reach Michael's extraordinary heights. And identifying racially with a white 400 runner, or basketball player, or stud of all stud positions, cornerback, if there are any still in the NFL, is a very minor and benign form of group identification, one that doesn't preclude a deeper human identification with any great athlete of whatever race. It goes the same way with blacks crashing through barriers: At the 3-meter springboard diving yesterday (which I found strangely sleep-inducing despite the endless parade of virtuoso triple somersaults and tucks and twists), I found myself pulling for the black Brazilian diver Cesar Castro.

It isn't complicated: White people don't run fast. Not only do they not win the 400, they don't win the 200 or the 100 either. It's no secret that if you need to put the pedal to the metal, don't turn to the Caucasians. Sure, every now and then the U.S. will boycott an Olympics, or some pea-brained track coach will give his athletes the wrong starting time so that when they show up at the stadium after four years of grinding workouts, the race is already over. And when that happens, the Alan Wellses and Valerie Borzovs of the world get to have their little medals. (Oh yeah, there was also this Greek guy, Konstandinos Kenteris, who came out of nowhere in Sydney to win the 200. He's currently running faster than ever, being pursued by the Furies in an exciting, real-life production of "The Eumenides." More on him and the whole Greek drug hoo-hah in the next piece.)

But something is changing. Maybe it's just because of drug disqualifications, which knocked out the top black women sprinters. Or maybe white people are eating their spinach -- or something a little stronger. (The Olympics drug carnival, which now has reached Ionesco-like proportions, makes trying to figure out reasons for any athletic achievements futile: Any grand theory you advance is likely to be embarrassingly refuted by a cup full of pee.) Whatever the reason, in the women's 100 on Friday night, I and the rest of the crowd watched with mouth agape as a lanky Belorussian with bangs named Yuliya Nesterenko flew down the track to beat American Lauryn Williams and Jamaican Veronica Campbell for the gold. For skeptics wondering how the sleeper Nesterenko managed to win, let it be noted that she offered the following homely explanation: "First of all, we finally got our own apartment, me and my husband. Before we used to live with my parents and it wasn't comfortable." The Eastern bloc countries have apparently come a long way from the days when state apparatchiks doled out dachas, cars and steroids to a chosen race of superhuman hermaphrodites.

And then there was Wariner. In the semis Saturday, he came flying out of the blocks and cruised to a 44.87, faster than anybody else, and you could just feel a gazillion track fans around the world eyeballing him and saying, "Is that a tan, or what?"

That was just the semis, though. A 20-year-old white kid from Baylor was not going to win gold in an Olympics 400.

But he did.

For a spectator, every distance has its unique joys. The 100 is just pure predation, it shoots you through the heart. The 200 is a delirious double shot of the same. The 800 is almost too painful to watch; the 1,500 is the gold standard, requiring the perfect blend of speed and endurance. The longer distances conjure up invincible images of man tracking down his quarry across the plains, with strides implacable as the movement of the earth.

But the 400, for me, is the most heart-quickening race of them all. Anyone who was in Sydney and watched Cathy Freeman, with her gloriously fluid stride coming around the last turn, and Michael Johnson, with that unique, almost ungainly straight-up stance, his churning legs and mighty chest a force no power in the world could defeat, powering down the back straight to victory, will carry the memory forever. The 400 is a race for cheetahs or leopards, at once explosive and silky smooth, run most of the way at 95 percent. If you aren't stirred as they flash in front of you through that first turn, discipline, talent and beauty united, the embodiment of what the ancient Greeks called arete -- excellence -- you don't like sports.

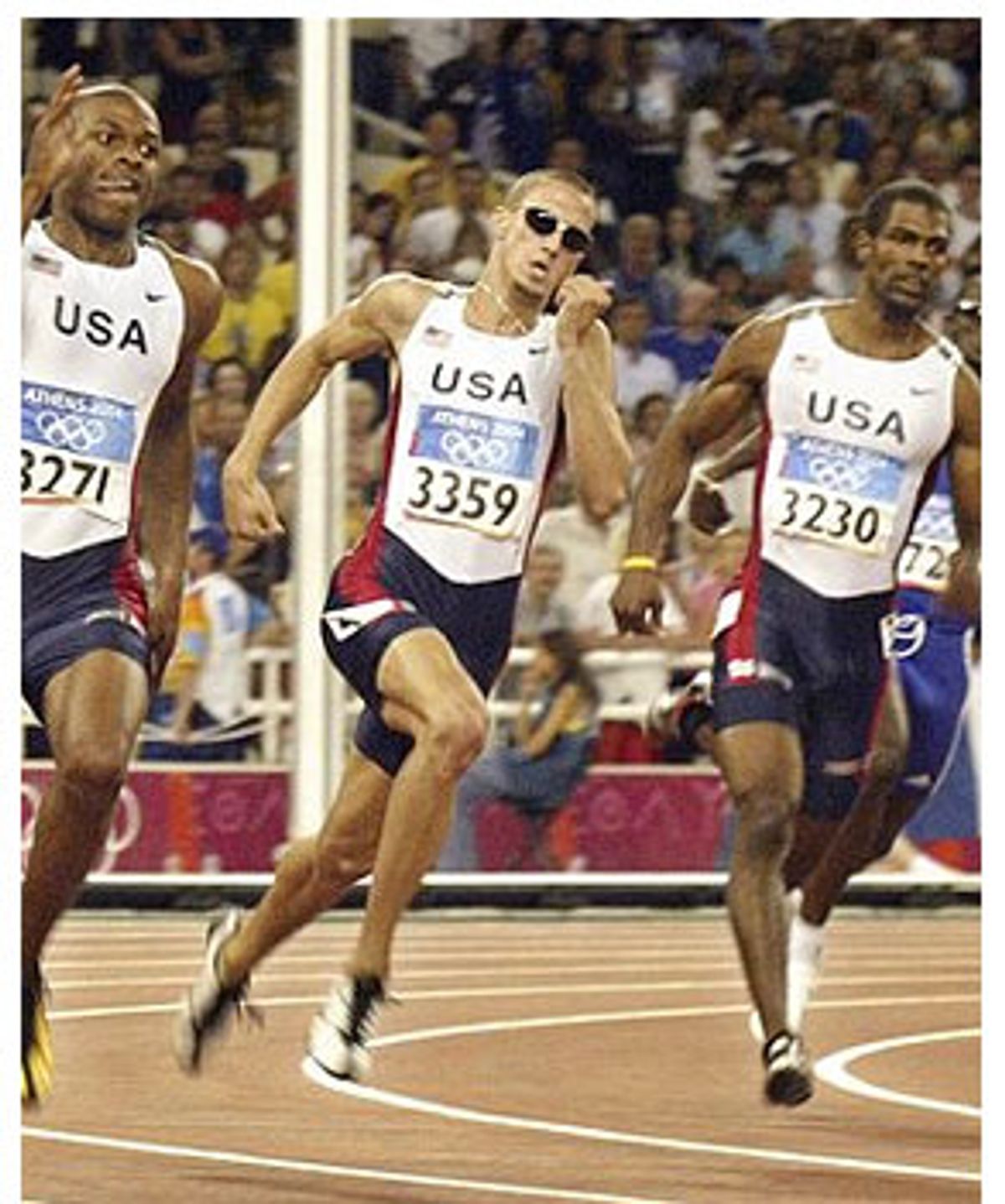

They settled into the blocks. At 6 feet, 170 pounds, Wariner has a longer, leaner physique than either of his two American teammates, Otis Harris and Derrick Brew. The field exploded away at the gun. Harris, who has a more muscular and powerful style, challenged Wariner for the early lead, but Wariner held position, with the crowd roaring, and on the home straight opened it up and showed why he was the class of the field. Harris pushed him all the way to the wire, but Wariner, whose viciously elegant, ground-devouring stride is so pretty you want to store it away somewhere so you can take it out from time to time and look at it, stayed in his own little Flash world, ignoring the express train a few inches away, and held him off to win in a fast 44.00. He was the eighth-fastest man ever to run the 400. Wariner didn't even seem to be breathing hard as he crossed the line, and his face behind the sunglasses was as blank as Apollo's.

When they announced that America had swept the medals, I let out a major scream, which was greeted with a just-barely-polite silence by the two very large Greek men squeezed in on either side of me and by the passionately flag-waving, Greek-rooting fans who surrounded me in my cheap-seat section in the corner of the stadium. There aren't a lot of American fans here, far fewer than at Sydney, and those who braved Osama's evil minions, totally incorrect rumors of Greek incompetence and the almighty euro to come here, are keeping a very low profile. Screaming loudly because the U.S. had swept the medals in an event, it suddenly occurred to me, could easily be interpreted by Greek fans as a vaunting, Dick Cheney-esque move, the Olympic fan's equivalent of Achilles dragging Hector around the walls of Troy. Oh well, too bad: As the three Americans took their victory lap, I yelled and screamed some more.

I have mixed feelings about the new U.S. restraint. It's true that the Ugly American Fan is tiresome, and it's useful for us Yanks, accustomed to blindly bigfooting the world at the Olympics and everywhere else, to find ourselves outnumbered and none too well regarded. (As is true throughout Europe and even the Middle East, the antipathy for America is for the Bush administration and its foreign policy, not for Americans. The Greeks, although a complex and not effusive people, have been more than friendly and helpful to me.) On the other hand, you've got to cheer for the home team -- why not? I cheer for everybody, especially the Greeks, who several times seem to have been lifted up by the enormous hand of their rapturous countrymen and moved several meters down the track, as happened the night before with unheralded Greek triple-jumper Hrysopiyi Devetzi, who was elevated by the crowd to a silver medal. And the truth is that American fans aren't any more obnoxious than any other fans.

Later, before an almost-deserted stadium, most of the Greek fans long departed, Wariner stood on top of the medal platform. He was blinking now, and with his shades off, he looked utterly confused, overwhelmed and young -- not the ultra-cool, racially ambiguous, wigger dude I imagined him to be. He was just a rangy boy from Texas who grew up running like the wind and had just run his way into history. The joy was left to be expressed by teammate Harris, whose deep, inward-looking smile, crowned by one of those glorious wreaths, was as easy and satisfying as Sunday morning.

It couldn't get much better than that, but then it did. On the big screen in the stadium, who should appear but Michael Johnson, the legend himself, taking a picture of the three young men who had just taken one step toward filling his golden shoes.

Miles from the great white Olympic Stadium, in the labyrinthine streets of the Plaka at the foot of the Acropolis, the 500-ring circus of the Games roars on. At 4 a.m. Saturday night, Monasteraki Square is the center of the world! It must be 85 degrees out and thousands of people, mostly young and in various stages of euphoria, lust and inebriation (a bar down the street has a huge banner reading "Citius, Altius, Fortius, Drinkius"), are milling around, looking for action or a souvlaki. At the closing ceremony in Sydney four years ago, the ritual call went out, summoning the "youth of the world" to come to Athens, and all of them seem to have heard it, these stylishly dressed Greeks and singing, yellow-draped Swedes and blond Poles in red and white capes and ruddy open-faced Aussies in absurd green and yellow leprechaun hats and maybe even an ingenuous, furtive American or two.

Four men wearing T-shirts marked "Iraq" careen across the square near the Metro station, one of them beating loudly with a stick on a drum hanging from his neck, celebrating their victory in football, letting everyone know, letting themselves know that they're here and happy to be here. An American and an Iraqi pass, under this silly and marvelous truce created so that 3-meter platform diving might peacefully endure.

It's a great feeling to realize that at this moment, in these streets, there are more people from more different places than anywhere else in the world. Maybe it's that, and the ever-ticking clock of the Games themselves, that gives the whole scene that uniquely joyous, sharp-edged Olympics buzz, that sense that big things are happening all around you, that these two weeks are blazoned and will never come back. The Olympic Games can be banal, and exhausting, but it's our planet's one and only block party, and at times it lets you see the earth a bit the way the astronauts do, whole and small and precious. Other times, you wonder why deodorant has not become universally accepted.

Then there is Athens. The Acropolis, much higher than you remember, is a constant affront, reminder, question, dream: It can't actually be there, but it is. You look over your shoulder, above the throngs, and it is still there, and it stops you in your tracks. Of all the monuments of antiquity, it is the most unsettling, because we are still in a conversation with the ancient Greeks, still moving down the questioning, probing course they charted 2,500 years ago.

And so the fact that the Games are here in Greece, where they began in 776 B.C., is endlessly beguiling. Sometimes it feels meaningless; other times almost unbearably evocative. What thread runs between that vanished age and this? Does the spirit of an ancient runner somehow reach out across the endless centuries to place a baton in our own hands? The answer depends on your mood. On Monday, you're a soaring Platonist, making connections between the ideal form of the games of ancient Attica and our own age. On Tuesday, you're an earthbound Aristotelean, denying that the alien culture of the ancient Greeks, and their all-male, religious, death-tainted athletic festivals, has much to do with us at all.

But the stones are still here, and when the wind blows just right through the ancient Kerameikos, the cemetery, long-vanished faces and never-vanished questions stir like ghosts, like memories -- of mocking Aristophanes and corrosive Socrates and proud Hector and cold-eyed Athena and the sad-faced little baby reaching out with stone arms for its dead mother, and that nameless red and black figure running on an urn, and all the rest of the gods and mortals who we do not understand, who we talk to constantly, who made us what we are.

Shares