With so many of the world's big cats and other great predators facing extinction, it's comforting to hope that captive breeding and cloning could stave off their end.

But producing ready-for-the-wild tigers takes a lot more than generating a living specimen from a test tube and letting it go in a suitable preserve. If you can kill but not disembowel your prey, you won't make it as a tiger in the wild. And who exactly will teach you the finer points of quadruped food preparation if you grow up in a lab?

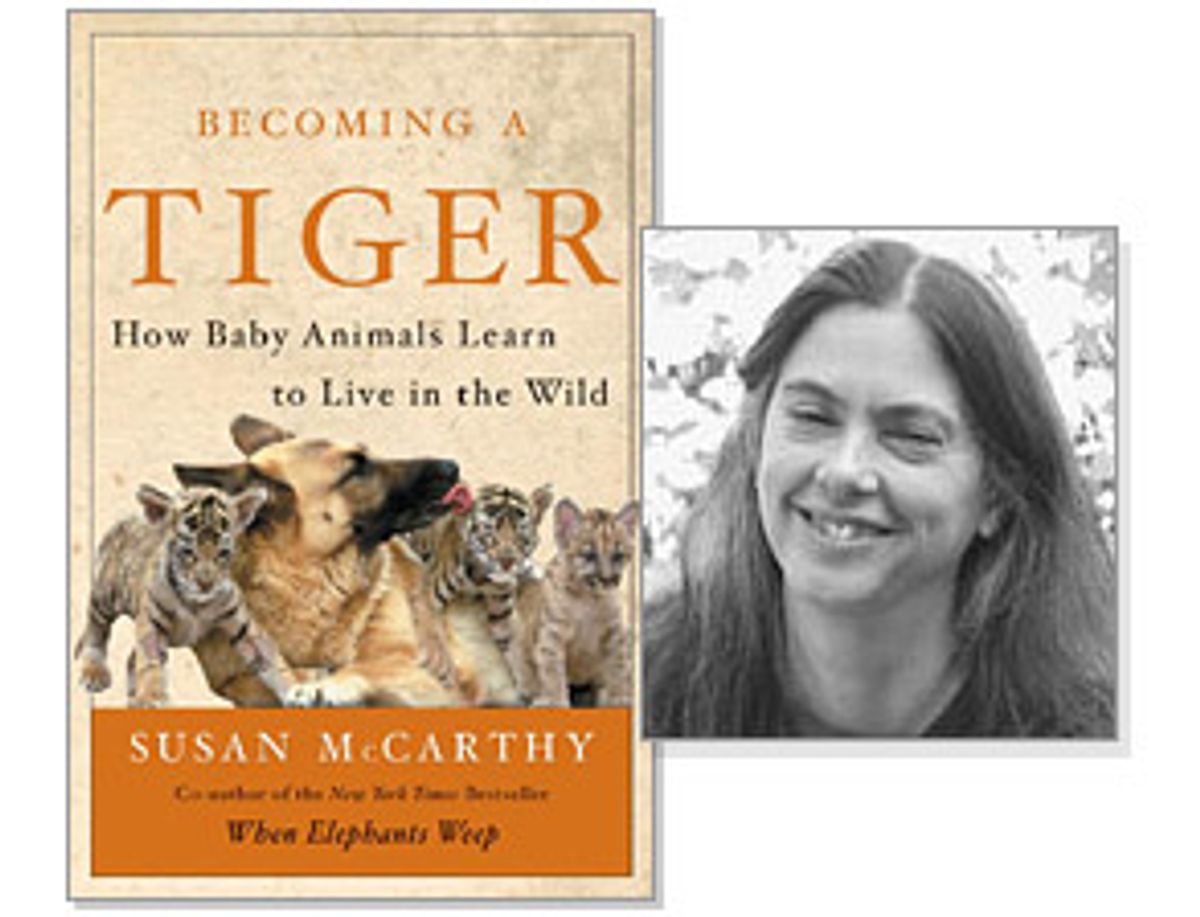

In "Becoming a Tiger: How Baby Animals Learn to Live in the Wild," Susan McCarthy explores the ways that innate and learned behaviors interplay in the lives of elephants, zebra finches, otters, leopards, tigers and other wild things. She finds that despite the irrational yet oddly tenacious human fantasy that animals "just know" how to thrive in their natural habitats, there's much that baby animals have to learn to survive, including skills and knowledge apparently as basic as foxes are not my friends. Even some invertebrates, such as the octopus, have the ability to acquire new skills over the course of their short, solitary lives.

The coauthor of "When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals, " with Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, McCarthy is a frequent contributor to Salon, who has tackled everything from grease rustling to the search for immortality, in our pages. In an interview at Salon's San Francisco headquarters, where she also keeps an office and worked on this book, McCarthy explained why it may be easier to breed and raise many animals in captivity than to equip them for life in the world their parents came from.

What animal behavior were you most surprised to find is learned and not innate?

Recognizing water. Baby chicks can be insanely thirsty and standing in a puddle, and not realize that they are ankle deep in a substance that would quench their thirst. This never causes a problem, because chicks instinctively peck at specks, so they soon peck at a speck floating on water, get a beak full, and instantly realize what great stuff water is.

What is the biological advantage to learning versus being "hard wired"?

Learning is a much faster way to get behavior that tracks a changing environment than evolution is. In Oakland [Calif.], there's a market with a big fish department, and black-crowned night herons have taken to perching on the awnings by the dumpster, waiting for fish to be discarded. Awnings and dumpsters are recent features of the environment, and if herons had to wait to evolve a dumpster-recognition module in the brain, they'd be missing out on a great food resource.

Instead they learn -- and noticing where other night herons are perching is probably part of their learning process. They learn and eat.

How hard is it for wildlife rehabilitators to really teach orphaned animals what they need to know to function in the wild while trying to keep them from becoming habituated to humans?

Wildlife rehabbers do it out of the goodness of their hearts. And when you're doing something out of the goodness of your heart for a darling baby animal, it's really hard not to become friends with that baby animal. But in many cases, that's the worst thing you can do for that baby animal if you're planning for it to be an adult animal living in the wild. So they really have to fly in the face of their natural inclinations.

And if you're trying to teach a baby predator how to disembowel another animal...

If you're trying to teach a great big predator how to kill prey, that's a pretty difficult thing for a human being to teach. Because we don't have those skills and tools. We're terrible at disemboweling antelope.

That's a perfect example of something that sounds like it would be innate but apparently is not.

That's a very interesting way in which innate stuff and learned stuff interact. The little cats we live with and the big cats that live in the wild, like the tigers, have hard-wired behaviors involving being interested in little sneaking, scuttling things. They crouch, stalk, sneak up and pounce. But it's really quite another matter to put that together into a whole suite of behaviors where you've identified creatures that are good to eat and not fatal to attack, and then put all those behaviors together, and actually kill the animal, and kill prey often enough to make a living.

There's a story of the orphaned lion who was raised by rangers in a South African game preserve, and who took as his role model their Australian cattle dog. And was very, very interested in wild antelope and learned to herd them.

His interest in wild antelope was hard-wired. He had lots of innate behaviors, like sneaking, crouching and pouncing. But he had no idea at whom to direct that, so he pounced on his friends when he was playing with them -- the dog and the people. He was very interested in impalas, but the dog, his role model, herded them, so he herded them, too. Not a good way for a lion to make a living.

So, if the lion was learning in the wild, it would learn by watching what its parents do?

Lions are a good example, because they go around and hunt things in the daylight in open spaces, so we can observe them. There's a lovely account of a lioness killing a zebra, and being watched by cubs as she does it. And they can't all have been her cubs, because there were 13 cubs, all lined up.

It's like zebra-killing school. You write at one point: "It may be possible to save a species through captive breeding but to lose its culture when no wild individuals are able to pass what they have learned to subsequent generations." What animals do you most fear this happening with?

Well, it's very likely to happen with a lot of tigers. For example, the South China tiger appears to be completely extinct in the wild. China has plans to fence off a huge area as a nature preserve, reintroduce prey species that have been wiped out and reintroduce the South China tiger from zoo animals.

But, of course, those zoo animals are going to be pretty clueless. So that's going to take some kind of program to teach South China tigers how to make a living.

What things are the hardest for humans to teach animals?

There is so much that we don't understand. For instance, creatures that live in the water, like a dolphin. It's very hard for us to teach echolocation, which we haven't got. It can swim so much better than we can, it's as if we can't swim at all.

One of the nice cultural behaviors that I found out about in doing the research were these dolphin/human fisheries in southern Brazil, where wild dolphins go into the murky water where human beings can't see the fish, and they essentially point to the fish.

The human beings throw nets over the fish, and they get the fish that they catch in the net, but some of the fish try to escape by swimming out under the net. So, the partnership helps the dolphins catch fish, too. It's been going on for more than 150 years, according to local records. And no one teaches the dolphins except for their mothers.

And if that was something, hypothetically, that we wanted to teach dolphins, we're just not equipped to do it. And there must be all kinds of things that dolphins and whales do that we haven't detected, haven't seen, know nothing about.

It's interesting to read about people trying to teach young birds to fly. We can't fly. You may have noticed that. But parts of the behaviors of flying are hard-wired in young birds, but other things they have to learn. Young birds should learn to land into the wind. Because if you land with the wind behind you, the wind is liable to push you right off your feet, and you'll fall on your beak. And it's hard for people to demonstrate that to birds. But if they're raising goslings, as Konrad Lorenz did, they can summon them in such a way that they land into the wind.

And the Durdens, who raised a golden eagle, were particularly well equipped to teach an eagle, because they had experience as small-plane pilots. So, they knew a lot of stuff about small planes and wind that they were able to try to pass on to Lady.

But there are other things that they can't teach her, like, "That branch is too small. If you land on that branch, you'll fall off." That she had to learn for herself.

What was the most improbable creature that you found actually learns things? The most apparently stupid?

Octopus and squid. They're invertebrates. They're not closely related to us at all. And they lack some of the things that are usually associated with learning ability. Most of the animals that are able to learn a lot learn when they are children, sheltered and protected by their parents. By the time an octopus hatches out of the egg, its mother has died. It has no parents to take care of it.

A giant octopus may live, like, four or five years. An animal with a short lifespan that isn't protected by its parents -- why would it have as much learning ability as octopus do? And they can learn quite a bit. They can learn by observing other octopus, which doesn't seem like something they would get much chance to do in the wild. So the fact that they can learn as much as they do is somewhat mysterious.

What sort of things does an octopus have to learn?

I don't think we really know much about what octopus have to learn. In the lab, they can learn from looking through a tank wall and seeing another octopus doing it. "Aha. So, that's how you open the jar and get the crab out." It may be that an octopus has a very complicated body. It's got 50,000 muscles and no bones to bounce them off of. They've got very complicated skin -- they can change the shape of features and patterns on the skin.

They also have, in some cases, many forms in their life. So a baby octopus is a little teeny thing you could hold in the palm of your hand, and a Pacific giant octopus gets to be a great big thing. And they catch different foods when they're at different sizes in their lives. So maybe they're using the learning to adapt to their constantly changing body shape and size, but that's just speculation.

Another thing that really surprised me that had to be learned is the very idea that you live in the forest. These animals that are raised in captivity and then are released don't just jump into the nearest trees, and go swinging off.

"Oh look, it's my natural habitat!"

Maybe it's a childish or romantic notion that of course they would just be free, run free!

Oh, absolutely. I was really amazed that Arjan Singh, who raised this leopard cub -- the first time he took this leopard into the jungle, its eyes got big. And essentially it said: "Let's go back to the house. This is scary. There could be monsters in there."

This happened to me when I was in high school. One of my teachers correctly surmised that I was just the sort of sucker to raise three orphaned possums whose mother had been hit by a car. And I raised them, at home, and one day I took them out into the woods thinking that they would love their natural habitat: the woods. And they took one horrified look at the woods and swiveled around and raced up my leg. Because the woods are scary. There are things out there that might want to eat possum.

That's another one: the idea that certain animals will prey upon you. The fact that you have to learn which ones they are, in some cases, seems so counterintuitive. Isn't knowing that one of the basic ways you stay alive?

Yes, it is. And I think that what is hard-wired in children and baby animals, I speculate, is a generalized fearfulness. I think we see that in children a lot, where we have children who are incredibly protected, and we try to make sure that no danger ever comes near them. And there you have a child who is terrified of fire trucks, who is terrified of bugs, who is terrified of imaginary creatures, bogeymen and werewolves.

I think that children -- human children -- have a natural need to be afraid, and if they're not supplied with bears and rattlesnakes, they'll find things in their world to be afraid of. Baby animals also have fearfulness, but they also have to be taught what to be afraid of. And this is something that people reintroducing baby animals into the wild have a terrible problem with. Because most baby animals are just like me. They say: "A fox! How cute!" And they don't think: "A fox! It's going to eat me."

They need to learn what to be afraid of. In the wild, they learn by watching their parents' reaction. If their parents shrink down to the ground and freeze when they see a fox, the baby animal instantly knows that the fox is bad news. If their parent freezes when they hear an alarm call, then the baby animal knows that the alarm call means something is scary. Seeing your parents afraid -- that's a very impressive thing to a baby animal.

Human beings are like some other animals in that we're not born afraid of snakes and insects, but we're born very easily able to learn to be afraid of snakes and insects. A monkey is not instinctively afraid of a snake, but if it sees another monkey act afraid when it sees a snake, then the monkey instantly learns. Whereas if it sees another monkey act afraid when it sees a flower, it won't. It's just not as easy to learn to be afraid of flowers as it is of snakes.

Speaking of monkeys, can you please debunk the "100th monkey" theory? Where does this idea have its genesis, and what does it really mean?

This is this great story that has been told different ways by different people. Basically, there are Japanese primatologists on an island studying the wild macaques. And in order to get good looks at the macaques they had gotten the macaques used to their presence, and one of the ways they did this was with bribes -- by putting out food on the beach -- so the monkeys would come to get the food and the primatologists could spy on them.

So the monkeys stared coming down to the beach to get food, and the primatologists started putting out sweet potatoes. And as you know if you've ever had a lovely picnic at the beach, sand gets on your food, and it's very annoying. After a while, one of the monkeys, a young female named Imo, started taking her sweet potatoes to the stream that ran down the beach and rinsing them off.

And her playmates learned this from her. And then her mother learned this from her. And her mother's friends learned it from her. And the information gradually spread throughout the troop. The kids who were Imo's age learned it first. And then the mothers learned it. And then the older males who didn't hang around with the women and children that much learned it last. Gradually they stopped taking them to the stream, but washing them in the ocean instead, allegedly for the salty flavor.

Then, later, the primatologists offered the monkeys grain, which they threw on the sand. And of course you get a lot of sand when you scoop up grain off the sand and try to eat it. So, Imo -- the same monkey -- developed the custom of taking up a handful of grain and sand and throwing it in the water. The sand would sink, the grain would float, she'd scoop it off the water and eat it. And the other monkeys copied this from her.

This was a very well-documented and interesting case of cultural learning, of imitation. Some scientists came up with various arguments for why it wasn't as smart as it looked. And other people celebrated Imo as a monkey genius. Imo was apparently a smart monkey and an innovator, but the stuff she invented was not that hard for macaques. And other macaques are capable of inventing it. And, in fact, some of the macaques on the other nearby islands also came up with these ideas.

Then a book was written called "The Hundredth Monkey" [by Ken Keyes Jr.]. And this book -- which is, I believe the technical description is woo-woo -- postulated that once a certain number of monkeys had learned techniques like washing sweet potatoes or throwing sandy grain in water, that all of a sudden all the monkeys knew.The theory was that the monkeys on the other islands didn't get to see Imo and the others doing it, so they must have learned it, like, through ESP or infinite race memory or something like that. So the idea was that if enough monkeys knew something then all the monkeys knew it. And just for fun, they took the number 100. If 100 monkeys slowly and laboriously learned something, then suddenly all the monkeys would magically know.

And the way that this was extended to humans is that if enough of us became enlightened and good and sweet and un-warlike and so forth, if enough of us were really nice people, then suddenly all of us would be really nice people, which is a really easy, relaxing way to effect social change.

Because all you have to do is get your 99 best friends to also be really nice?

Exactly. And it's not true about monkeys, and I'm pretty sure it's not true about people.

Why are juvenile or younger animals, like Imo, often innovators who invent new ways of doing things?

Well, this is the period in life when they have to learn a lot. So it is the period when they are inclined to learn a lot, when they are interested, when they are curious, when they have an insane amount of energy, when they're not busy making a living because their mothers and fathers are feeding them and protecting them. So they have lots of spare time and lots of interest.

Scientists used to think that certain practices separated humans from animals, like the ability to use tools. But now we know that's not a true distinction. Do you think it's just hopeless to try to draw these lines in the sand like that? Or is the difference between humans and animals more of a question of degree?

That's my hypothesis: that it's quantity, not quality. As you say: "Man uses tools." OK. "Man makes tools." OK. "Man, uh, teaches others to use tools. Oh wait."

It's always possible that there is some behavior that we've got and no other animals have, even one little bit. But so far I haven't seen any evidence of it. It mostly seems to be a matter of degree. They've got the same stuff that we have, but we've got a lot more of it.

How can animals be superstitious?

Animals develop superstitions the same way that we do, which is to say that they do a behavior, and it's followed by something rewarding or something negative. And we assume that there is a cause and effect. If you wash your car, that doesn't really make it rain. But if you wash your car and then it immediately rains, that's extremely noticeable. You, the human, are developing a superstition.

My dogs bark hysterically every time the package delivery truck comes. This has gotten more extreme with the years. Basically, they have a superstition, which is, if they bark loudly enough they will scare away the guy in the package delivery truck, and he will leave. Sure enough, he comes. They bark. After a while, they scare him badly enough that he leaves. They don't realize that he is just leaving because he delivered a package. They're not scientists. They never do the control experiment and say, "Oh, what happens if we don't bark?"

Are species that survive the loss of their natural habitat especially good learners? I think about raccoons and coyotes and crows and ravens, animals that do well in cities. Or does that have more to do with being willing to eat a lot of different foods?

Well, certainly the animals that survive in different habitats and changing environments tend to be generalists. And a lot of the generalists are smart: coyotes, jays, ravens, crows, raccoons and rats. But they're not all smart. I was very fond of my possums, but they're not real bright. An opossum will eat rotten fruit, kibble that it finds on your back porch, and anything it finds in the dumpster. So, while lots of learning ability is really helpful if you're a generalist, it isn't mandatory.

What did you learn about teaching from studying animal learning?

In all these cases where we're trying to teach things to animals, it turns out we're actually not very good at teaching things to animals. We make a lot of mistakes. We're always trying to drill them and give them lessons and lectures, and show them educational films. It works terribly.

One simple example that really impresses me is with baby zebra finches who have been raised in isolation by humans who tried to teach them zebra finch song by playing them tapes. And they didn't learn. Who likes to listen to educational tapes? They found if they let the baby finches press the buttons on the tape recorder themselves it made all the difference. They would play the songs. They would flutter up and down in front of the loudspeaker like somebody dancing in front of the amp at a rock concert, and they would learn, because they had some control.

It causes me to wonder if we're not really bad at teaching things to people. I think if kids get to push the buttons -- it works for animals, and it seems like common sense that it works for people.

There's no wildlife equivalent to the eight-hour classroom day?

No, in the forest there are no blackboards. Oftentimes, animal parents teach by letting their children watch or by providing learning opportunities. The mother animal will bring a prey antelope to her cubs and let the cubs try to deal with it. A father bat-eared fox will catch a sun scorpion, and put his foot on it, and then take his foot off, and let his cubs try to catch it themselves. There are killer whales that ride onto shore and catch seals, and demonstrate it for the young ones.

There's also a tremendous amount of eavesdropping that goes on in the wild. Wild animals are always spying on other animals to see what they're doing, even when the other animals aren't trying to teach them. It's a survival mechanism. It's good to know what is going on.

Shares