A perennial favorite in moviedom, the concept of love that extends beyond the grave is supposed to be deeply romantic. But ideally, shouldn't dead people mind their own business, instead of coming back to announce to the bereaved, "Just thought I'd check in, see how you're doing, and by the way, I'll love you forever -- feel better now?"

Setups like these usually mean we're headed for the zombie zone of movies in which a valuable and necessary lesson is about to be imparted -- "Life is for the living!" pretty much sums it up. The ghost, of course, isn't really a ghost at all, but a symbol of the bereaved's inability to let go and get on with things. And the ghost's love isn't love at all, but a screenwriter's construct. Ah, romance!

Still, there's a market for this sort of thing, and Jonathan Glazer's "Birth" is the latest to slither out of the canal. "Birth" is a little like the '80s crowd-pleaser "Ghost," but way artier. Nicole Kidman plays Anna, a young woman who, 10 years after suddenly losing her husband, reluctantly agrees to marry Joseph (Danny Huston), the nondescript, vaguely menacing suitor who has been poking her in the ribs for years, even as he's maintained an air of polite patience with his little filly's unabating grief. We know it's a mismatch, because we see Anna and Joseph making love (missionary position, natch), and we catch the glazed, detached "What is this guy doing on top of me?" look in Anna's eyes as Joseph dutifully grinds away.

But Anna's life is about to change -- again -- when a 10-year-old boy barges into a birthday party for her mother (the salty Lauren Bacall, as unlikely a mom for the ethereal Kidman as you could possibly cast) and announces that he's Sean, Anna's dead husband. This grade-school spudling gravely tells her not to marry Joseph, a dictum he reasserts by sending her little notes written in kiddie handwriting. She, and Joseph, try to make him go away, but he won't -- he repeatedly shows up, making bullying declarations like, "I love Anna, and nothing is going to change that. That's forever."

But this little, living Sean knows many intimate facts about big, dead Sean, and about Anna, as well -- things that only big, dead Sean could really know. And so Anna begins to wonder if, just maybe, this little Sean really is big Sean. Her doubts puzzle and anger those around her, particularly Joseph, who, at one point, scrambles over a baby grand piano to -- get this -- spank the disruptive little squirt.

There's a twist in "Birth," an implausible one. But it's all intentionally implausible. The fact that "Birth" doesn't make a whole lot of sense isn't its major flaw: Logic is overrated in movies. When a movie makes emotional sense, it doesn't necessarily need the other kind. But "Birth" is the kind of movie that keeps alerting you to its resonant emotional undertow without actually having one. It's completely different in tone and style from Glazer's first picture, 2001's "Sexy Beast" -- it has none of that movie's playfulness or crafty intelligence.

Shot in mushroomy tones by Harris Savides (much lauded for his work on "Elephant"), "Birth" moves along solemnly, at an obsessively controlled pace, holding its placard scrawled with meaning and portent stiffly before it. The movie was co-written by Glazer, Milo Addica (co-writer of "Monster's Ball") and Jean-Claude Carrière (who collaborated with Luis Buñuel on "Belle de Jour" and "The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie," among other pictures). Carrière's involvement suggests that we need to be open to threads of surreal consciousness buried deep beneath the movie's surface. But the picture, as a whole, never gets beyond its surface: It's like a painting that allegedly depicts the power of grief when what's most obvious is the artist's obsession with the texture of the paint.

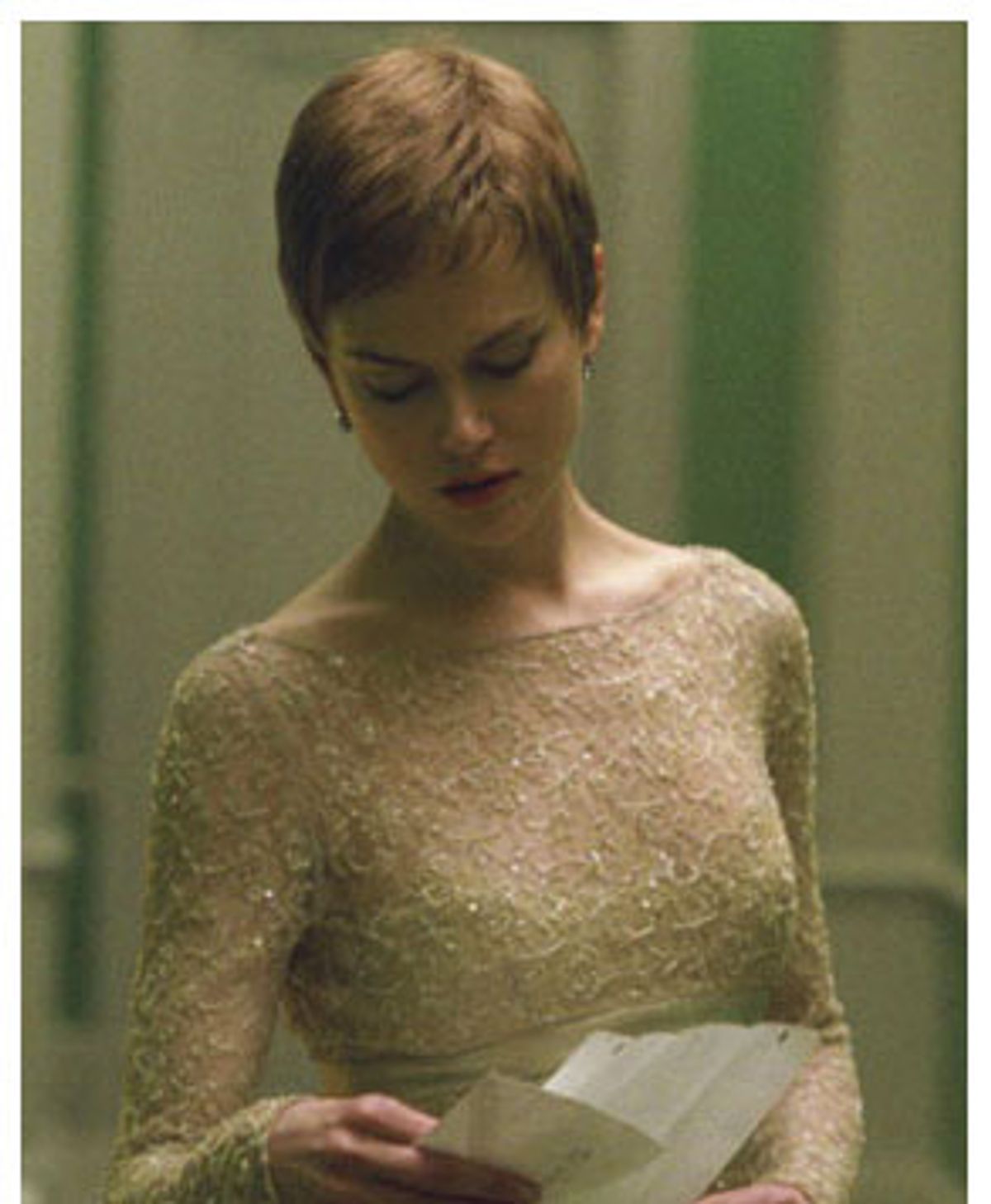

Kidman works hard here, as she always does: A respectful and thoughtful actress, she always bends, like a supple reed, to curve into the shape required by the material she's given. Here, she seems even more transformed by her short, dark pixie haircut than by the fake schnozz she wore in "The Hours," and as that nose did, the fringey crop momentarily jogs us into forgetting that it's Kidman we're watching on-screen (to the extent that such forgetting is necessary or even desirable).

But it's hard to know how to respond to Anna's character, because we can't quite understand what she's responding to. Young Sean appears at her doorstep, a good-looking kid who, by the movie's design, is a blank. But he's a creepy blank. His face is a round, flat moon that yields no light -- he may talk a good game about being the "real" Sean, but he has no aura to speak of. It's not the fault of the actor who plays him (Cameron Bright) -- in the movie's later scenes, we see glimmers of vibrancy in the kid, suggesting that most of the life has been purposely directed out of him.

I think we're meant to realize that Anna is so taken with what he's saying that she doesn't even see the boy in front of her. At one point, he enters the bathroom as she bathes, undresses with more quiet dignity than most 40-year-olds can muster, much less 10-year-olds, and slips into the tub opposite her, holding her gaze like a shaman. Even though the scene isn't at all overtly sexual, it should feel charged -- a scene like this one is, after all, pretty risky, given how people tend to react to anything involving kids and sex. But the sequence is drab and lifeless. It suggests how far Anna, in her confused desire to have her "real" Sean back, might possibly go.

But all of the potentially powerful feelings explored in the movie -- Anna's yearning for her dead husband; young Sean's love for Anna, which seems merely professed and not felt -- are rendered so blankly that they recede into oblivion. Kidman's big speech, in which she confesses to her friends that she knows this can't be Sean, but that she believes it anyway, is rendered with all the appropriate shifts in expression and vocal tone -- I'm not sure any actress could do better, but it's still not good enough. Anna's emotional fragility is putty in the hands of Glazer, his co-writers and cinematographer: There's nothing left for an actress to do but work the material into its predetermined shape.

Other actors' drift about listlessly: Anne Heche appears, mysteriously sans eyebrows. Arliss Howard plays a boring doctor-slash-brother-in-law. Bacall, as the matriarch of a very rich (and, we're to gather, somewhat sheltered) family, delivers a few lines loaded with crusty, if misguided, good sense, because, well, what else do you do with a presence as nakedly sensible as Lauren Bacall's? At one point her character, prompted by nothing, announces, "I never liked Sean."

This assertion, as well as many other bread-crumb clues left by the movie, makes us wonder: Was Sean really all he was cracked up to be in Anna's eyes? It's not important, really -- all that matters here is Anna's mirage vision of her late husband. But by the end of the movie, we start to think, Hey, I never really liked Sean, either -- and we never even knew him. The dead often have great power over the living. But it's all too easy for moviegoers, even without 3-D glasses, to see right through them.

Shares