In his new book "The Road to Whatever: Middle-Class Culture and the Crisis of Adolescence," Elliott Currie, an internationally recognized authority on youth and crime, says that irresponsible adults are responsible for the current epidemic of troubled, drug-addled teenagers. In an angry indictment of middle-class culture, Currie claims that punitive and uncaring parents, hands-off institutions and a societally pervasive "sink or swim" attitude are largely responsible for the problems suffered by many American teens. Woe is the teen that becomes addicted to drugs or alcohol, Currie says, because there is shockingly little support available.

Currie's conclusions are based on in-depth interviews with over four dozen white, middle-class young people who are, as he puts it, "suffering through a desperate period of their adolescence, or looking back at that period from the vantage point of a few months or a few years later." Many came from a separate study of teens in treatment for substance abuse that Currie conducted on behalf of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and others were students or former students of his. Currie feels that too much of our knowledge of adolescents come from adults, so in this book, he includes long, unedited passages in the teens' own words.

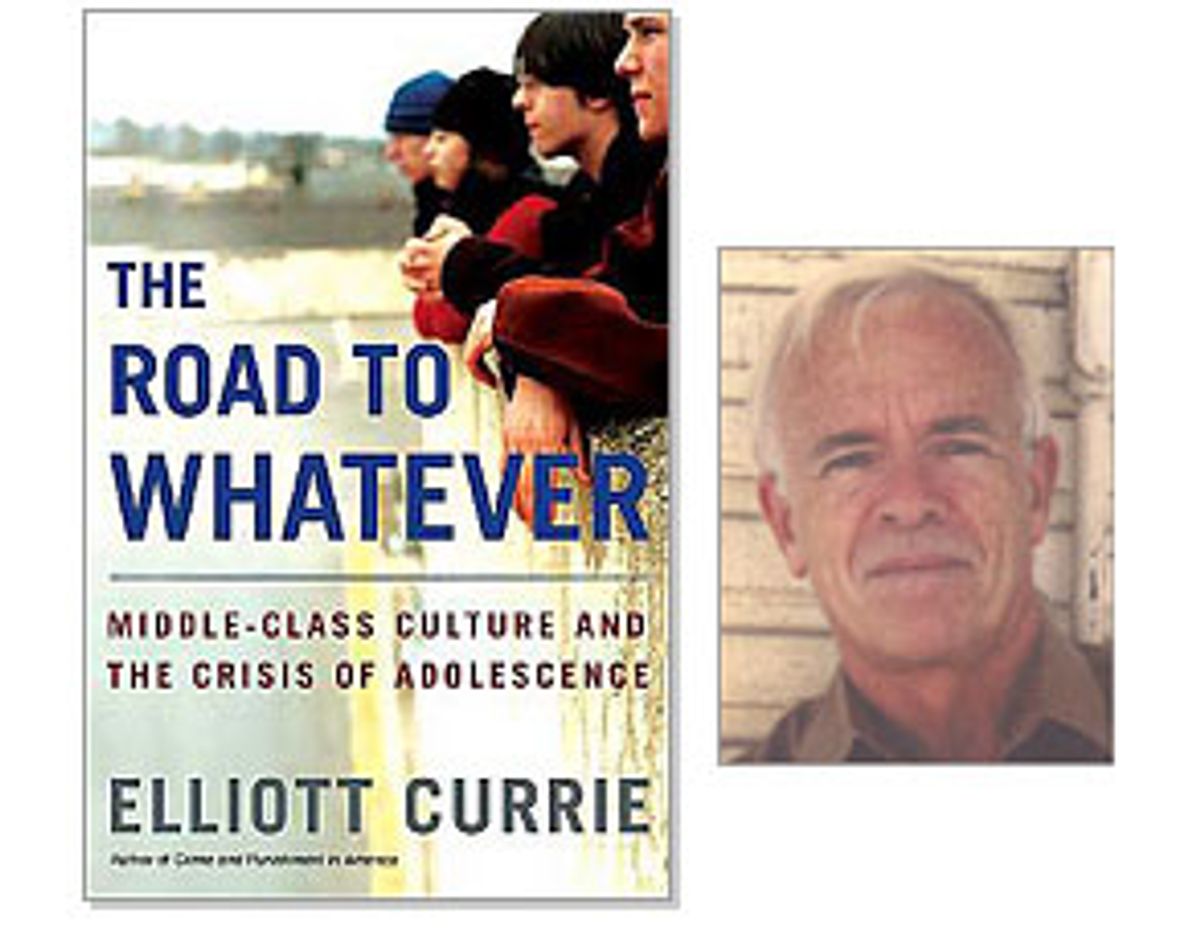

A professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California at Irvine, Currie is also the author of "Crime and Punishment in America," a finalist for the 1999 Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction. Currie spoke with Salon by phone about parents who don't have time for their troubled kids, teachers who don't bother to help their floundering students, and teens who don't care about anything.

You write that troubled teens become jaded and often distrustful of adults and authority. How did you get these teens to open up to you?

I spent a lot of time developing a rapport with them. I've done a fair amount of that kind of work before -- I once worked with kids in a juvenile hall -- and over the years I have found that if you can convey that you really want to hear them out as opposed to preaching to them, then they open up.

Let's talk about this "crisis" of middle-class adolescence. Do teens have more problems today than they used to?

One of the things I try to argue in the book is that middle-class kids have always had it rougher than we nostalgically think. We've been in denial of the state of middle-class youth since back when I was a teenager in the late 1950s and early 1960s. There have always been more problems and pressures than we were willing to confront. Even scholarship has ignored them, has not tried to understand their problems and what causes them.

However, I do think there are several ways in which things have gotten worse: There are the school shootings, the emergence of white gangs as a suburban phenomenon (that existed when I was a kid, but not on a level they do today), and especially, the prevalence of drugs.

What made you focus on troubled middle-class teens?

When the high school shootings took place, it almost seemed as if no one had ever thought about these things before. A major newsmagazine put the perpetrators of the Columbine massacre on the cover with the headline, "The Monsters Next Door." We were throwing up our hands and saying, "What is going on here? How can the kids next door do these horrible things?" One of the things I wanted to prove with the book is that we have a very good idea of how this can happen -- and the kids themselves can articulate that for us.

You talk about a state of the teenager's mind that you call "care-lessness." What do you mean by that?

"Care-lessness" is coming to a state where you really, truly don't care what happens to you -- you don't care whether you live or die. You don't care what happens to anybody else, either. I got that word from interviews with the kids. It came up again and again.

But isn't it characteristic for teens not to have a sense of mortality, to ignore the threat of death when they're doing dangerous things?

I'm skeptical of the notion that kids have an ingrown sense of invincibility. I think it's kind of true, but we lean on it too much. I think when you see a kid who is acting as if they have no sense of mortality, or believing themselves to be invincible, it's because they don't care. The kids themselves would bring out that distinction. "It wasn't just that I didn't think it could happen to me," they'd say. "It was that I wouldn't care if it did."

How do you justify the scale of your conclusions about the "crisis" of middle-class adolescence considering you spoke to a relatively small sample of teenagers?

I got to know these kids really well, and I interviewed them five or six times apiece. I developed a striking level of rapport with them. They come from all over the country (Florida, New York, California, Texas, etc.), and they are from all parts of the middle class. Some were quite affluent; some were children of police officers and department store clerks. When you have so many kids touching on the same themes again and again, you can safely say you're on to something.

There are a limited number of people you can get to know really well to do the kind of interviewing that I think produces the best work. That isn't the only strategy for learning: You can send out thousands of surveys to high school students, but their answers will be shallower and more structured. For example, there is an important annual survey that is done through the University of Michigan about drug use. It is cut and dried, and it doesn't really get into things like, How does it feel to get really wasted? Why do you [abuse drugs]? It's a much more distant kind of study. Of course, that type of research is very valuable. But that's not how you get to know what kids are really thinking about.

A major impetus for this book was that we do a lot of pontificating about what's wrong with kids, but the voices of the kids are missing. I feel quite pleased with the richness and complexity of the information that I got when I talked to kids.

You write that while our society assumes that teens with alcohol or drug problems must come from a lenient, overly indulgent family, the truth is the exact opposite.

There may be kids who decide to drink themselves into oblivion because people are too nice to them, but I haven't met them. I've talked to plenty of kids who get to that place in their life because people treat them badly.

It is not just the parental pressures to do well. It's growing up in a family where if you don't do well, you get thrown out of the house. And if you don't do better than everyone else in school, your parents tell you that you are a piece of crap. This combination of harshness and responsibility from adults has increased. The specific abnegation of responsibility for the child on the part of parents, schools, helping agencies -- that was a constant theme. I would argue that is new. On the level we experience it now, it's qualitatively worse than it used to be.

Do a lot of parents threaten to throw their kids out of the house?

An extraordinary number of kids in the book were thrown out of their home at least once. In addition, a study [by the Family Research Laboratory at the University of New Hampshire] found that nearly one parent in five had threatened to throw a teenage child out of the house during the previous year. This seemed to be the default response of parents to their kids when things got really bad.

You note that the kids you spoke to were frustrated with social workers, therapists and counselors who kept emphasizing personal responsibility. You write, "Since it was generally assumed that people's difficulties in life were due to their own 'bad choices,' the job of the helping agencies was ... to offer them the tools to help themselves." In defense of the helping agencies, doesn't that response play into the ideas of developing self-sufficiency and empowerment?

Of course we want kids to ultimately become self-reliant and capable of charting their own path. But that doesn't mean you can set them loose and say "sink or swim." The "tools" that the treatment agencies give kids tend to be the moral exhortation to "look inside" themselves and "stop being a bad person," "make better choices." Those are not tools to negotiate the kinds of situations these kids face. In fact, the very notion that there is some tool that you can just give people and they can stand on their own two feet for the rest of their lives -- that is a very peculiar way of looking at human behavior and dealing with it as a society. You need social support and institutions that are there to help.

What are some better examples of "tools" that would actually help these troubled teens?

Effective and powerful education, so that they have some philosophical view of world challenges. Serious aftercare and follow-up programs, where they can get additional counseling after they come out of rehabilitation or an institution. We, as adults, have to help teens direct their own lives and become self-reliant. You can't kick them out of the nest and expect them to do that all by themselves. What I saw going on with the helping agencies mimicked what was going on in schools and family: Everyone was just shrugging their shoulders and looking away.

What about medication? In the book, you talk to a number of teens who became fed up with all of the medication they were on -- the ones most commonly mentioned were Prozac and Depakote -- and eventually rejected the pills. "B.J.," who had problems with drugs, self-mutilation and depression, criticized her doctor because "he was like, 'Well, we'll just give you this pill.'"

Drugs are, among other things, a cheap, easy, un-engaging way to deal with people's problems. The kids would say, "It's not that some kids don't need medication; they need a whole lot more than that." They need people to listen to them, ameliorate some of their problems. If your only response [as a doctor] is to "shit out the pills," as B.J. put it, that really is kind of a cultural tendency toward a quick fix.

In the book, you describe the way we deal with our troubled adolescents, with an attitude of "harsh individualism" and sink-or-swim "social Darwinism," as being particularly American condition.

That attitude is more extreme in America than anywhere else. It goes along with other things we see in us that differentiate us from other industrial societies. We are the country that doesn't provide much of a safety net to our people. We are the quickest to incarcerate people if they break the law. We have no universal health program. We don't give family allowances.

What are family allowances?

Family allowances are social-policy measures that many European countries have. Families are automatically provided with a certain amount of money that is supposed to go toward child-rearing expenses. It's a grant that is designed to provide a floor under every family. It's not welfare. It's more of a resource like universal health care.

Back to what I was saying: In America, we force people to rely on themselves and their wits to get by in their life, and we, as a country, explicitly reject the idea that we should be helping them. It's not accidental that we see these characteristics in their more intense form after a period of almost 25 years during which the hard right dominated our country's social and cultural institutions. This individualism is an essential part of how they look at the world.

What role did religion play in lives of the teens you talked to?

There are strands of religion in American (and elsewhere) that create this "either/or" situation for kids. You're either a good little kid on the right side of the Lord, or you're a sinner on the side of a devil. If you're on the side of God and you screw up even a little it means you're bad. As "B.J." said in the book, "If I'm already bad, I may as well be even badder."

We hear so much about the negative effects that the media has on teens. But the media and pop culture never come up in your book.

The reason the media isn't in there is because the kids didn't talk about it. When I asked them about their problems, the media didn't factor into their response, and so I didn't push it.

The kids in this book make high school sound like prison, and their teachers sound like wardens at best and evil sadomasochists at worst. "Zack," an aggressive, confrontational teen who "got in a couple of fights [with] his teachers once or twice," complained that the teachers at his high school "treat you with no respect" and that some unfairly prejudged him. But was Zack easy to have in the classroom? What is the responsibility of the teachers in dealing with difficult, disruptive, teenage addicts?

It shouldn't be their responsibility alone. Right now, they're the only adults outside the family who have the responsibility for keeping kids under control. They don't have any backup. They don't have any support system themselves. There need to be other adults in the community who can take some of the load off the school in the first place, like community-based programs that could provide help for kids having trouble in school. This would take some of the pressure off teachers.

I say the same things about the parents. These parents are put in a bad situation. There is so little help for them. Where do you turn when you have a kid who is a real handful? In many places in America, there isn't anywhere to go.

You talk about the things that schools, teachers, treatment centers should do, but don't: identifying troubled kids, establishing aftercare programs, setting up safe havens for kids to run away to. But these things would cost a lot of money.

Many of these things need not cost a lot. We could think of making use of volunteers. I talk about the possibility of enlisting retirees, for example, or college students. The students I met who were troubled adolescents said they would want to help that troubled community. There are so many people who would be willing to take on that role, who wouldn't need a salary if they feel like they're doing something important for people who need them.

It's very expensive to deal with kids the way we do now: Neglect is very expensive. The kid who doesn't have a decent, honorable counselor in high school may turn up again and again in emergency room, or he may crack up or kill people -- that situation will cost a lot of money when it reaches that phase. But you can head that off with relatively modest interventions like aftercare programs, safe havens, mentors. It's not rocket science. Most of these kids just need someone who pays attention, gives advice, gets them on the right track, helps them with their schoolwork.

How realistic do you think these ideas really are?

A lot of people [in the current administration] talk about mentoring and volunteering, they talk about all some of the same solutions that I do -- as long as it doesn't involve money. They could make some of those programs happen. If they actually did it, if they put their energy where their mouths are, we might see some improvement.

You come down very hard on parents, treatment centers, mental health professionals -- pretty much everyone in the adolescents' lives except the adolescents themselves.

I wound up being harder on parents and school personnel than I expected. That's partly because when I talked to some of them, I was appalled at the way they perceived parenting. We have to realize that there are a lot of parents out there who don't want to do the job of parenting. It's hard. It involves sacrificing your own pleasures, taking on a very responsible role, which is beyond the capacity of a lot of American parents.

Why do you think contemporary parents have such a difficult time parenting?

In the book I provide two answers: One, it's a problem of resources. Parents are pressed for time and money. In addition, there are very few sources of social support for parents. We're continually taking away money for childcare, school counselors, things that could help parents do a better job of parenting. We don't provide resources the same way many other countries do: universal childcare benefits, vacation time, family allowances.

One of the reasons these problems are getting worse is the hardening of the culture that lies behind this. Careless individualism has become our modus operandi. This behavior has roots in our individualist heritage, but it is sharpening in the 20th and 21st century. People are unwilling to take responsibility, unwilling to think about the consequences of their actions, whether it be barreling down the freeway in a Hummer and not caring about other drivers, other people, or the environment -- it's the same mentality.

Shares