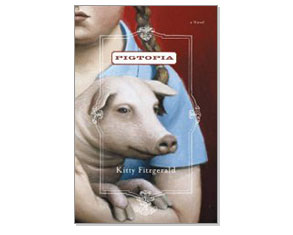

Jack Plum’s pigs can dance. They can also play the xylophone, walk at heel, find flowers and explosives by smell, relieve themselves in a chemical toilet and visit a sacred place, deep in the forest, where in ancient times persons or pigs unknown carved a “pigrelicstone.” If these sound like elements of a fairy tale or a fantasy novel, they are, sort of. But actually, pigs in the real world can do those things, or most of them (I’m not sure about the pigrelicstone). If Kitty Fitzgerald’s enchanting and tragic “Pigtopia” often feels like a fable — indeed, like a religious parable — it never completely departs from the realms of the possible or plausible.

Among domestic animals, the lot of the pig is a uniquely tragic one. They are strikingly intelligent and inquisitive creatures, more easily trained than dogs or horses, and are not naturally messy or dirty, despite their reputation. Pig farmers often view their charges with affection, but in the end there is only one destination for the pig; its usefulness to humankind is pretty much limited to breakfast, lunch and dinner. This may be why the pig plays such a potent and ambiguous role in literature: “Animal Farm,” “Charlotte’s Web” and “Alice in Wonderland” all testify to the strange status of the porcine race.

Jack Plum has those books, and refers to them often. He is a misshapen boy-man, an autodidact genius who has never been to school but has built a secret “Pig Palace” beneath his mother’s house in a northern English town. The story of Jack’s unlikely friendship with a lonely teenage girl named Holly Lock is always destined to end in sadness; Jack knows that the “outsideworld humanpigs” view him as a freak, and will destroy him and his pigworld on the slightest pretext. “Letting the outsideworld in to my Palace with Holly did give possibles access to all its despairs,” he reflects.

Once you get accustomed to it, Jack’s pig-patois is this novel’s greatest wonder. It seems a little precious at first, but eventually Fitzgerald makes clear that Jack’s invented language (vaguely reminiscent of those in Anthony Burgess’ “A Clockwork Orange” and Russell Hoban’s “Riddley Walker”) expresses not childlike innocence but rather a species-bridging combination of animal intuition and human wisdom. It’s Holly who innocently hopes that she can redeem Jack in the town’s eyes, and that one day they’ll be able to live together openly. “I know there is not one probable of longtime future things for me and Holly,” Jack tells himself. “There is just this momentness, this now time.”

Jack cares not just for his pigs but also for his mother, who is dying slowly in a welter of booze, tuberculosis and mental illness. Holly has a close and affectionate relationship with her own single mom, but a much more problematic one with her so-called best friend, the vain and damaged Samantha. Neither Jack nor Holly could manage all this without each other: Jack can provide Holly some insight into the puzzling adult world around her, while Holly can help Jack confront doctors, insurance companies, the post office and the Internet. (“It is extreme massive knowledge box what works from electrics and radio and phone things what you can ask great questions from.”)

But as Jack knows all along, their friendship must be kept an airtight secret and in the long run that won’t be possible. You could say there’s a kind of eroticism between Jack and Holly (and indeed their beloved “piggylets”), but there’s no sex; whatever their innermost longings may be, Holly is too young and Jack too careful for that. Needless to say, Samantha and Holly’s mother and the rest of the town’s “humanpigs” are likely to draw the wrong conclusions about midnight meetings in the woods between a deformed man in his mid-30s and a girl barely to the age of puberty.

Jack has consulted the Boar Star and murmured words at the pigrelicstone and dwelled on the subject in his long, lonely hours. He has a plan to save the pigs and himself too, after a fashion, now that “the big stones what will crush the Palace is rolling fast at us.” But the really important thing, he sees, is that Holly “must be total freed of the freak connection” if she is to go on and live her life in the outsideworld. If this sounds like an unutterably tragic direction, it is and it isn’t. In the end, Fitzgerald wants us to see “Pigtopia” as a tale of redemption and transformation, not of loss. Some may resist her conclusion, with its overtones of Christian mysticism, but there’s no denying this novel’s sweet-tempered blend of wonder, heartbreak and, of course, “pigsense.”