On Tuesday, Dec. 20, Washington Post polling editor Richard Morin participated in an online chat with readers. The liberal blog MyDD urged its users to take part, and evidently they did. In previous days, legal experts had declared that Bush had committed a federal crime by authorizing the surveillance of American citizens without a court order, and Morin was grilled about the issue of impeachment.

First, someone from Naperville, Ill., asked Morin why the Post hasn't polled on public support for impeaching Bush. "This question makes me mad," Morin replied. Someone else repeated the question and Morin typed, "Getting madder." It came up again, and he wrote, "Madder still."

Finally, a fourth person asked it, and he answered: "[W]e do not ask about impeachment because it is not a serious option or a topic of considered discussion -- witness the fact that no member of congressional Democratic leadership or any of the serious Democratic presidential candidates in '08 are calling for Bush's impeachment. When it is or they are, we will ask about it in our polls."

Morin was wrong. It may be exceedingly unlikely that President Bush will be impeached, but in the past few days, the I-word has become a topic of considered discussion among constitutional scholars, former intelligence officers and even a few politicians.

"If you listen carefully, you can hear the word 'impeachment,'" curmudgeonly commentator Jack Cafferty said on CNN. "Two congressional Democrats are using it. And they're not the only ones."

Indeed, speaking on the Diane Rehm show on public radio, Norman Ornstein, a scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, said, "I think if we're going to be intellectually honest here, this really is the kind of thing that Alexander Hamilton was referring to when impeachment was discussed."

On Dec. 17, after the story of Bush's domestic spying broke in the New York Times, the president conceded that he had ordered the National Security Agency to intercept Americans' communications without seeking judicial approval. Unrepentant, the White House insisted that Bush had been granted such authority by the post-9/11 congressional resolution authorizing "all necessary force" in the fight against terrorism, and that the president would continue to order warrantless searches.

The next day, during a public discussion with Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., former Nixon White House counsel John Dean called Bush "the first president to admit to an impeachable offense." Boxer took Dean seriously enough to consult four presidential scholars about impeachment.

"This startling assertion by Mr. Dean is especially poignant because he experienced firsthand the executive abuse of power and a presidential scandal arising from the surveillance of American citizens," she wrote to them. "Given your constitutional expertise, particularly in the area of presidential impeachment, I am writing to ask for your comments and thoughts on Mr. Dean's statement."

Boxer has not made public any of the responses yet. But other political scholars have weighed in. "The American public has to understand that a crime has been committed, a serious crime," Chris Pyle, a professor of politics at Mount Holyoke College and an expert on government surveillance of civilians, tells Salon. "Looking at this controversy objectively, you inevitably end up with a question of impeachment," says Jonathan Turley, a professor at the George Washington University School of Law.

On Dec. 18, Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., the highest-ranking Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee, released a 250-page report detailing Bush's misconduct and, on his Web site, called for the creation of a select committee to investigate "those offenses which appear to rise to the level of impeachment." Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., said in a radio interview that he would support trying Bush. "If there is a move to impeach the president, I will sign that bill of impeachment," he said.

Assessing the controversy, Newsweek columnist Jonathan Alter wrote on Dec. 19, "This will all play out eventually in congressional committees and in the United States Supreme Court. If the Democrats regain control of Congress, there may even be articles of impeachment introduced. Similar abuse of power was part of the impeachment charge brought against Richard Nixon in 1974."

It was bracing to see impeachment mentioned as a possibility in the mainstream media. But experts say it's not unreasonable. According to Turley, there's little question Bush committed a federal crime by violating the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

The act authorizes a secret court to issue warrants to eavesdrop on potential suspects, or anyone even remotely connected to them, inside the United States. The bar to obtain a FISA warrant is low; more than 15,000 have been granted, with only four requests denied since 1979. In emergency situations, the government can even apply for FISA warrants retroactively. Nevertheless, Bush chose not to comply with FISA's minimal requirements.

"The fact is, the federal law is perfectly clear," Turley says. "At the heart of this operation was a federal crime. The president has already conceded that he personally ordered that crime and renewed that order at least 30 times. This would clearly satisfy the standard of high crimes and misdemeanors for the purpose of an impeachment."

Turley is no Democratic partisan; he testified to Congress in favor of Bill Clinton's impeachment. "Many of my Republican friends joined in that hearing and insisted that this was a matter of defending the rule of law, and had nothing to do with political antagonism," he says. "I'm surprised that many of those same voices are silent. The crime in this case was a knowing and premeditated act. This operation violated not just the federal statute but the United States Constitution. For Republicans to suggest that this is not a legitimate question of federal crimes makes a mockery of their position during the Clinton period. For Republicans, this is the ultimate test of principle."

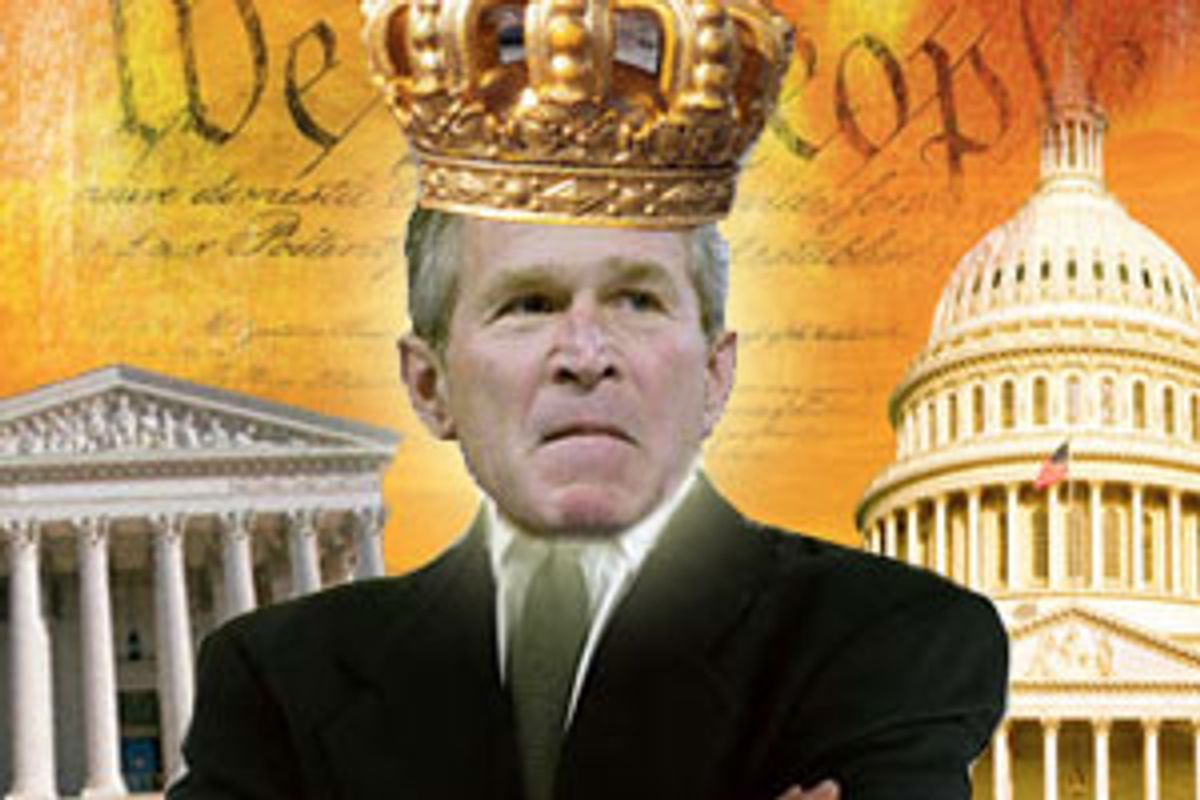

Of course, that may be exactly the problem. While noted experts -- including a few Republicans -- are saying Bush should be impeached, few think he will be. It's not clear that the political will exists to hold the president to account. "We have finally reached the constitutional Rubicon," Turley says. "If Congress cannot stand firm against the open violation of federal law by the president, then we have truly become an autocracy."

Similar fears are voiced by Bruce Fein, a former associate deputy attorney general under President Ronald Reagan. Fein is very much a member of the right. He once published a column arguing that "President George W. Bush should pack the United States Supreme Court with philosophical clones of Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas and defeated nominee Robert H. Bork."

Suddenly, though, Fein is talking about Bush as a threat to America. "President Bush presents a clear and present danger to the rule of law," he wrote in the right-wing Washington Times on Dec. 20. "He cannot be trusted to conduct the war against global terrorism with a decent respect for civil liberties and checks against executive abuses. Congress should swiftly enact a code that would require Mr. Bush to obtain legislative consent for every counterterrorism measure that would materially impair individual freedoms."

What alarms Fein is not only that Bush has broken laws but also that he has repeatedly shown contempt for the separation of powers. Fein wants to see congressional hearings that would explore whether Bush accepts any constitutional limitation on his own authority.

"The most important thing to me, in terms of thinking about the issue of impeachment, is to recognize that the Constitution does place a value on continuity," Fein says. "We don't want to have a situation where you make a single error, and you're exposed to an impeachment proceeding."

Fein says Congress should probe Bush on whether he plans to keep "skating the edge" of federal law by trying to concentrate power in the executive branch. "That's the key. It's that probing that's essential to knowing whether we're dealing with somebody who's really a dangerous guy. If he maintains this disregard or contempt for the coordinate branches of government, it's that conception of an omnipotent presidency that makes the occupant a dangerous person. We just can't sacrifice our liberties for ourselves and our posterity by permitting someone who thinks the state is him, and nobody else, to continue in office."

In fact, though, that may be exactly what America is permitting Bush to do. "Politically, I see no possibility that impeachment will succeed," says Jonathan Entin, a professor of political science and law at Case Western Reserve University.

"The Democrats are a minority in both houses of Congress," Entin says. "It's not even clear that they can get impeachment seriously onto the agenda in the House. Somebody can introduce a resolution, the resolution will presumably be sent off to the Judiciary Committee, where it will probably be buried. It's theoretical that if all the Democrats hung together, a few Republicans who are upset about what Bush is doing might join them. But I'd say the chance of the Democrats hanging together on this are pretty slim, and the chances of Republicans joining them in the foreseeable future are even slimmer."

"The only question here is the political one," says Pyle of Mount Holyoke College. A former military intelligence officer, Pyle blew the whistle on the U.S. Army's domestic spying program during the Vietnam War. He believes that Bush has committed an impeachable offense -- and that right now there's no prospect he will be impeached. "This president has admitted committing the crime. He just claims he's above the law," Pyle says. "So the issue is: Is the president above the law?"

If so, Pyle continues, "then we need not argue over the PATRIOT Act. We do not need the PATRIOT Act, because the president can do anything he wants in time of war. He can ignore all the criminal laws of the United States, including the laws against indefinite detention and against torture. I don't think we want to go down that road."

But aren't we already down that road? "We may be," Pyle says. "Maybe it's time to call a halt."

Shares