What a sober year it was, this year in sports. An upstanding law-and-order year, a do-the-right-thing year. It was a year of new rules and regulations, stiffer penalties, the bad guys getting theirs. Humble lunch pail brigades took home championships this year while flash and self-glorification were sent into exile.

Except for Reggie Bush. The Heisman Trophy-winning tailback from USC was so spectacular that even this hat-in-hand, nose-to-the-grindstone annum couldn’t dim his luster.

Maybe the sports world was chastened by the Brawl of Palace Hills in November 2004, the consequences of which were felt well into ’05.

Maybe it was the prospect of playing games in the face of a wave of worldwide disasters, of tsunami aftermath and earthquake, war and, especially, Hurricane Katrina, that injected a note of humility to the proceedings and had athletes, coaches and the commentariat talking again and again about “perspective.”

Maybe it was just one of those years, and with one or two things breaking differently — high-flying Dwyane Wade staying healthy and leading his glamorous Miami Heat into the NBA Finals, say, or the New York Yankees going on one of their October runs — this theme wouldn’t fly at all.

Thank heavens for small favors.

The year began, as sports years tend to do, with college bowl games, and a massacre at the Orange Bowl. But the lasting memory from that National Championship Game wasn’t Southern Cal toying with Oklahoma on the way to a 55-19 smithereening. It was Ashlee Simpson getting booed off the stage at halftime.

It was as if sports fans were serving notice that this was a new day. Keep in mind this was the Orange Bowl, which is to impossibly cheesy halftime entertainment what Siberia is to ice. The assembled crowd had only moments earlier had no problem with Kelly Clarkson, a minimally talented, manufactured product of the instant-celebrity hype machinery.

And now they rose up as one to say no — they pronounced it “Boo!” — to the amateurish keening of Simpson, who isn’t even a minimally talented, manufactured product of the instant-celebrity hype machinery. She’s the untalented sister of one. “That’s where we draw the line,” the people declared: “Boo!”

What does this have to do with sports? Everything. It was a harbinger, a signal that 2005 would be a year of no nonsense. A few weeks later, that no-nonsensiest of football teams, the New England Patriots, won the Super Bowl for the second straight time — and with nary a costume malfunction during the forgettable halftime show.

The Patriots have won three of the last four Super Bowls without benefit of a superstar other than quarterback Tom Brady, a good-looking but unassuming fellow who is not going to make the popular culture forget Joe Namath. Or even Dan Marino. This blue-collar year saw a TV ad campaign make Brady’s offensive linemen almost as famous as he is.

In between those two championship football games, Minnesota Vikings wide receiver Randy Moss elicited outrage when he pretended to moon the crowd in Green Bay after scoring a touchdown and pitcher Randy Johnson, then the newest New York Yankee, was filmed acting imperiously and roughly with a TV news cameraman.

Those served as opening acts. By the fall the outrageous behavior of an NFL wide receiver and the assault of a cameraman by a major league pitcher would be two of the biggest sports stories of the year, but Moss, traded to the Oakland Raiders over the summer, and Johnson, who couldn’t fix the Yankees’ pitching problems, weren’t involved.

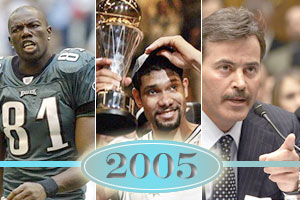

It was that other brilliant but temperamental receiver, Terrell Owens, who overshadowed Moss in 2005. He began the year by heroically returning from a broken ankle in time to play well in the Philadelphia Eagles’ Super Bowl loss to the Patriots, completely scuttling his reputation as an egotistical, team-poisoning jerk.

By August, he’d gotten himself thrown out of training camp for whining about his year-old contract and bad-mouthing teammates, particularly popular, good-guy quarterback Donovan McNabb. 2005 was not a year for taking on the good guy. In November Owens was suspended for the maximum four games and deactivated for the remainder of the season following his latest round of carping.

By that time, the Indianapolis Colts had taken over the NFL, winning their first 13 games and clinching home-field advantage throughout the playoffs before finally losing a game without stakes for them to the San Diego Chargers on Dec. 18.

The Colts launched their assault upon the Miami Dolphins’ 33-year-old record of being the NFL’s only unbeaten, untied champions behind an unabashedly spectacular offense — but one led by their own aw-shucks quarterback, Peyton Manning, and by receiver Marvin Harrison, as brilliant as he is unflashy, a sort of anti-Terrell.

But the Colts have had offensive firepower for years. They finally turned themselves from pretenders tormented by the Patriots to contenders streaking toward a title the old-fashioned way: with a tough, bruising defense. Only fitting for a team coached by Tony Dungy, who is, of course — this being 2005 and all — a no-nonsense, defense-minded boss.

Sadly, the Colts’ glorious year was marred by tragedy just before Christmas, when Dungy’s 18-year-old son, James, was found dead of an apparent suicide.

The pitcher who went one better than Randy Johnson was Kenny Rogers of the Texas Rangers. Johnson at least had the excuse, however lame, that he’d been accosted by a camera on a city street. Rogers was in uniform, on the field before a game, and the local news cameraman he attacked had as much right as Rogers did to be where he was.

Rogers became a pariah, booed at the All-Star Game and savaged in the press, which makes sense, one of its own having been attacked. But when a celebrity can’t get the people on his side in a beef with the intrusive media, something’s afoot.

Another important thing happened in that busy month of January, between those two championship football games: Major League Baseball announced a new steroid testing plan with stiffer punishments for offenders. It was the start of baseball’s Year of the Steroid.

In February, Jose Canseco confessed to — or bragged about — having been the Johnny Appleseed of steroids in the late ’80s and early ’90s. In his book, “Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant ‘Roids, Smash Hits, and How Baseball Got Big,” he wrote of teaching teammates such as Mark McGwire and Rafael Palmeiro all about performance-enhancing drugs, and even about shooting up some teammates with hypodermic needles in bathroom stalls.

At the time, Canseco was largely dismissed as a bitter attention whore telling tall tales. Within a few months, he was starting to look like the only honest man in the room.

The new program yielded suspensions for steroid use for the first time. Journeyman outfielder Alex Sanchez of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays was the first to get dinged for 10 days. Every few weeks another no-namer’s name would be announced, he’d issue a wan denial — must have been something mixed up in the stuff I got at the GNC — and then he’d serve his 10 days. It looked for a while like the program would only catch small fish.

But only for a while.

In March, not long after Yankee Jason Giambi, whose steroid use was made public in a December 2004 leak of grand jury testimony from the case against suspected steroid lab BALCO, issued a heartfelt apology to fans, teammates and the rest of the world without mentioning what it was he was apologizing for (it was his steroid use — Shhhh!), a group of current and former players, including Canseco, appeared before a congressional committee that was grandstanding about steroids.

At the hearing, McGwire, the retired, Bunyonesque slugger who had done a lot to help baseball recover from a devastating strike by breaking Roger Maris’ single-season home run record in 1998, refused to answer questions about whether he’d used steroids. “I’m not here to talk about the past,” he kept repeating.

In a matter of minutes, McGwire’s reputation as an American hero was destroyed. A few months later, McGwire, who’d worn a Cardinals uniform when he broke Maris’ record, was booed in St. Louis. No former Cardinals get booed in St. Louis. That fans there booed McGwire, who a few years earlier had had a section of interstate highway in town renamed for him, showed how badly he’d crashed.

But among the men sitting shoulder to shoulder in that congressional hearing room on that March day, McGwire got off easy compared to Rafael Palmeiro. The Baltimore Orioles star pointed his finger at the committee and said, “I have never used steroids. Period.” On Aug. 1, baseball announced that Palmeiro had tested positive for steroids.

He was suspended for 10 days like the others, but he was no Alex Sanchez. Earlier in the year — after his positive test but before his appeals were exhausted and the results announced, timing that some found fishy — Palmeiro had reached the 3,000-hit mark, which combined with his 500 home runs all but assured him of a spot in the Hall of Fame.

Now that enshrinement appears unlikely. Booed at home and on the road, Palmeiro was eventually sent home for the rest of the season by the Orioles, ostensibly to nurse a sore leg.

In September, Major League Baseball and the players union were again renegotiating the steroid testing plan, in hopes of avoiding threatened congressional imposition of a tougher standard. While this was going on, Barry Bonds returned from a knee injury that had sidelined him for the entire season.

Bonds had been a key figure in the BALCO case. He was a client of the lab and one of the defendants had been his personal trainer. His steroid use also came out in the leaked testimony, though he’d denied knowingly using. Now, 41 years old and with the sports world waiting for him to prove his doubters right, to show that he couldn’t do anything without steroids, he hit five home runs in 14 games, leaving him six shy of Babe Ruth’s career total.

Did that performance mean his astonishing hitting prowess of this century hadn’t been steroid fueled after all? Or merely that whatever he was juicing with wasn’t detectable by the current tests?

Or maybe he was just in that same period Palmeiro had been in when he’d hit his 500th home run, the time before his first positive test. The reality of the year of the steroid, of the whole steroid era, is that we just don’t know.

In November, the players and owners agreed on yet another, stiffer testing program, with a 50-game suspension for a first offense and a possible lifetime ban for a third. Congress backed off. Law and order had won the day.

In the meantime, getting back to the lunch pail side of our thesis, the Chicago White Sox won the World Series. This scrappy, superstar-free bunch — Paul Konerko hardly transcends the sport in Derek Jeter- or Johnny Damon-like fashion — brought the hard-working, blue-collar South Side its first championship since 1917.

And the Sox did so by beating the Houston Astros, who’d beaten the more glamorous Cardinals and Atlanta Braves to win the National League. The Braves, in turn, won the National League East only after the surprising, underdog Washington Nationals had spent much of the summer in first place. It was a stylish way for baseball to make its return to the capital, where it had been missing for 33 seasons.

Style was something that was missing from the NBA Finals in June. The fundamentally sound, defense-first San Antonio Spurs beat the fundamentally sound, defense-first Detroit Pistons for their second championship in three years and third in seven. Nose to the grindstone stuff, hard work and playing the right way paying off.

TV viewers stopped complaining about the lack of fundamentals in the modern NBA long enough to stay away in droves.

The only diva in sight for those dozens who tuned in was Pistons coach Larry Brown, who spent the team’s playoff run flirting with other clubs and ended up taking the head coaching job with the Knicks. In other words he was sent into a sort of exile, to a place far from the mainstream in this humble, down-to-earth year: New York.

The NBA had limped into 2005 stinging from a disastrous public-relations year highlighted by Kobe Bryant’s rape trial in Colorado — charges were dismissed in September — and the infamous November brawl between the Indiana Pacers and Detroit Pistons that spread into the stands.

Commissioner David Stern, who’d slapped instigator Ron Artest with a full-season suspension, scuttling the Pacers’ hope for a championship, pushed through two image-polishing initiatives in 2005. As part of the new union contract, the NBA now has a minimum age of 19 for players — Stern had been hoping for 20.

The new rule was supposed to encourage kids to stay in school for at least another year and reach the league with that much more seasoning and maturity. Of course it won’t hurt that they’ll arrive with a year’s worth of free NCAA publicity behind them too, but that’s surely nothing more than a happy side effect of doing the right thing by our nation’s youth.

Stern’s other innovation, a new business-casual dress code for players when on league business, such as traveling to games, got some laughable criticism from the millionaire players — Denver’s Marcus Camby said he wanted a clothing allowance — and, like almost everything that happens in the NBA, led to an interesting conversation about the role of race in a league of mostly black players that’s overwhelmingly run by and played for whites.

A group of elderly former players who had been NBA pioneers in the 1950s pushed hard during the labor negotiations to be included in the NBA’s pension plan, from which they’d been excluded since its formation in 1965.

Though NBA players and teams sent tens of millions of dollars to disaster relief during the year, they declined to shake loose the few hundred thousand that would have taken care of the 80 or so men, some in desperate financial straits, who had helped create the league’s wealth. Doing the right thing wasn’t universal in 2005.

Prospects for a more glamorous 2005-06 increased a little with Brown bringing some star power to New York’s long-dormant squad and the return of Phil Jackson to the Los Angeles Lakers’ bench, though neither team figured to still be around in June.

It might have been a perfect four-sport parlay of lunch pail-toting champions if some grinding, checking, superstar-free team had won the Stanley Cup, but the Stanley Cup wasn’t awarded. The NHL, in a lockout since September 2004, in February became the first North American sport to lose a season to labor trouble when it announced the 2004-05 campaign wouldn’t be saved.

The players eventually capitulated to the owners, agreeing to the salary cap they’d earlier refused to negotiate about. It was a total loss for the players, who got a worse deal than they could have without losing a year off their careers.

A positive side effect of this embarrassing disaster, the loss of a season because a group of a few hundred people couldn’t figure out how to divide up $2 billion, was that the NHL felt the need to win fans back by fixing the on-ice game, a move that was about a decade overdue. Liberalized rules led to an increase in scoring of about a goal a game in the early going of the new season. No longer was a two-goal lead insurmountable. Real progress.

“Disaster” is obviously a relative term. Poor decision-making in a contract negotiation is nothing compared to real-world disaster, and the sports world didn’t escape the effects of Hurricane Katrina.

The Superdome, home of the New Orleans Saints, the Sugar Bowl and numerous Super Bowls, was a briefly notorious relief shelter. Teams, leagues and players donated money, goods and time to disaster relief. Two major pro teams, the Saints and the NBA’s New Orleans Hornets, were forced to relocate.

The Saints moved their headquarters to San Antonio, playing home games there and in Baton Rouge. Already a struggling franchise, they may never return to New Orleans. The Hornets moved temporarily to Oklahoma City, a town that hopes to use the team’s presence to showcase its readiness for a franchise without appearing to capitalize on a tragedy.

And many college sports programs throughout the Gulf Coast region were affected. In New Orleans, Tulane “suspended” eight sports as a cost-cutting measure as it tries to recover. But Tulane was also responsible for a first, small flowering of good news: On Dec. 18, the Green Wave beat Central Connecticut State in women’s basketball. It was the first sporting event, college or pro, in the city since the hurricane.

As always, there were stars and heroes outside the four major North American sports. Lance Armstrong, chief among them, won his seventh straight — and, he says, last — Tour de France, though he remains under a cloud of doping accusations, charges he insists are false and motivated by European antipathy toward him. He remains a lavishly admired figure at home.

Tennessee’s Pat Summitt became the winningest college basketball coach ever, and Baylor won the women’s NCAA Tournament, a surprise that finally brought good basketball news to a campus that two years earlier had been home to one of the most sickening scandals in the history of college sports.

North Carolina survived a dazzling, thrilling Elite Eight round and beat Illinois — which had been undefeated before losing to Ohio State in its last regular-season game — for the men’s championship. Then the Tar Heels had four players taken in the first 14 picks of the NBA draft. Andrew Bogut of Utah, a slick-passing Australian center, was the top pick in the draft and began his pro career playing well for the Milwaukee Bucks.

In college football, while USC and Texas were No. 1 and No. 2 wire to wire and will play for the national championship in the Rose Bowl, Notre Dame and Penn State made headlines with huge comeback years.

Joe Paterno, the subject of “How do we get Joe to retire?” talk as he coached Penn State to a 26-33 record from 2000 through 2004, opened up the offense at long last and led his Nittany Lions to a 10-1 record and a Big Ten championship, the only loss coming at Michigan.

He was named Associated Press Coach of the Year the day before his 79th birthday. Ranked third in the nation, Penn State will play in a Bowl Championship Series game for the first time in the BCS’s 8-year history, meeting Florida State in the Orange Bowl Jan. 3.

In South Bend, former Patriots assistant Charlie Weis took over a program that had had only two winning seasons in the last six and immediately energized it. The Irish went 9-2, losing only a pair of thrillers at home, to Michigan State and, in the game of the year, Southern Cal. Notre Dame will play Ohio State in the Fiesta Bowl Jan. 2.

Speaking of comebacks, a 50-1 shot came from way off the pace to win the Kentucky Derby. Of course. In what other year should the little-known Giacomo roar down the stretch and win, rather than the much-hyped Afleet Alex, with his ready-made, heartwarming back story involving a brave little girl who died of cancer?

Afleet Alex overcame a trip at the start to win the Preakness, then took the Belmont Stakes too. Of course, because 2005 was all about doing the right thing, and who better to win two Triple Crown races than a horse donating a chunk of his winnings to pediatric cancer research?

Danica Patrick became the first woman to lead a lap at the Indianapolis 500, and more importantly returned that race, possibly temporarily, to the A list of American sports events, though NASCAR, whose Nextel Cup was won by former bad boy Tony Stewart, continued to dominate the world of speed.

It’s too late for such a figure to return the sad sport of boxing to the front pages. Here’s an example of how far the sweet science has fallen: On Dec. 17, a 7-foot Russian won the WBA heavyweight championship on a disputed decision over John Ruiz in Germany.

This whole thing, a freakishly huge Russian winning a questionable decision in a heavyweight title fight, barely made the papers in the U.S. If you can summon the name of the giant who now holds a share of what was, during this not-yet-old writer’s lifetime, the most important title in sports, you are in a tiny minority. It’s Nikolay Valuev.

And there was more crime and punishment as well. Temple basketball coach John Cheney suspended himself after he ordered a player to commit hard fouls against St. Joe’s in response to officials not calling moving screens, and that player broke an opponent’s arm, ending his career.

The BALCO case, the eye of the steroid hurricane for most of 2004 and ’05, fizzled, with founder Victor Conte and two others copping pleas and getting short jail sentences or probation.

The Minnesota Vikings, off to a terrible start in a season in which they’d been picked by many to win their division, made headlines with a bye-week bacchanal on a pair of Lake Minnetonka charter yachts that was cut short after the crew complained of players and their guests engaging in public sex and aggressive behavior.

Four Vikings players, including quarterback Daunte Culpepper, who was injured in a game shortly after the party, were charged with misdemeanors.

Unfortunately for the thesis of this piece, all of this was followed by the Vikings turning their season around, winning six straight games to launch themselves into the thick of the playoff picture, though they were eliminated from contention Sunday night with their second straight loss.

And the sports story from 2005 that will have the longest-lasting and farthest-reaching consequences for the most people had nothing to do with good or bad, right or wrong, humble or egocentric. It simply was what it was, a business story with no heroes or villains. But it meant the end of an era.

In April, the NFL announced two new television deals: “Monday Night Football,” the cultural icon that had brought the NFL to prime time in 1970, was moving from ABC to cable in 2006, to corporate partner ESPN, where one out of five American households wouldn’t be able to see it.

NBC would take over the Sunday night game, which the Peacock says will become the big prime-time game of the week. Disney, which owns ABC and ESPN, begs to differ, but there’s no denying that that little slice of Americana created by Howard Cosell and Don Meredith was in its last days as the year ended.

A sober, serious year. A nose-to-the-grindstone year. One with no place for Dandy Don serenading us, however appropriate the sentiment would have been, with “Turn out the lights, the party’s over.”

This story has been corrected since publication.