"Tell me a story," a young girl asks at the beginning of Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie's dizzying graphic novel "Lost Girls." We can't see her; all we can see, for the entire first chapter, is a mirror with an ornate carved frame, and whatever happens to be reflected in it. On the first page, that's a wealthy woman's bedroom in Pretoria, South Africa, in 1913. "Oh, I don't know any stories," the older woman says. "Your little white breasts, they're so lovely. They'll never be as beautiful once you're grown. Will you touch them for me?" All we can see of the woman is her leg, stretched out as she masturbates.

To put it bluntly, the scene is totally creepy; naturally, it's also more complicated than it looks. As it turns out, the woman is Lady Alice Fairchild, a drug-befogged upper-class Englishwoman in her 60s, and she's just talking to herself. The girl is her reflection in the mirror -- or, rather, the lost self Alice imagines on the other side of the mirror. Alice has extensive experience with imagination and mirrors; you've probably already encountered her younger self, the protagonist of "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking-Glass."

The themes of "Lost Girls" are all right there on the first page: storytelling as a way of making sense of the transformations that sex brings about, children's sexuality and its adult exploiters, and an almost Modernist formalism -- the idea that working within interesting and rigorously defined structures, no matter how outré they are, will yield worthwhile results. (We get the very strong impression that this is what Lady Fairchild always does to get off.)

Moore and Gebbie began working on "Lost Girls" in 1990, when Moore had already written graphic novels like "Watchmen" and "V for Vendetta" but wasn't yet as famous as he's become. (The first six chapters were serialized in the early '90s; the rest has never been seen before, and the project itself has practically reached the age of consent.) The finished version is an exquisite physical object: a $75, slipcased set of three oversize hardcover volumes, reproducing Gebbie's mixed-media artwork in luminous color. (Its publisher, Top Shelf, sold the first 500 copies at July's Comic-Con International; it will be nationally distributed in September.) Moore has been telling interviewers that the point of "Lost Girls" was to make dignified pornography, rather than "erotica" -- to produce something that was beautiful and well-wrought, and also overtly, unblushingly about what happens behind bedroom doors.

Another way of putting it is that it's a really advanced version of slash fiction, a sort of "I Am Curiouser and Curiouser." In short order, Alice finds herself at a hotel on the Austrian border, the Himmelgarten, where she becomes entangled, figuratively and literally, with beleaguered English hausfrau Wendy Potter and Midwestern farm girl Dorothy "Dottie" Gale, late of, respectively, "Peter Pan" and "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz." All three women have stories of their own, though: They've built grand metaphors -- pornographic-utopian worldviews, really -- around their adolescent sexual experiences. Naturally, those worldviews look very much like Wonderland and Neverland and Oz, right down to the styles of those books' original illustrations, except that everybody's doing everybody else -- boys with girls, boys with boys, girls with girls, and a few other permutations. (Toto is virtually the only character from the source books who escapes with his innocence intact.)

It's a brilliant move: Moore and Gebbie have found a consistent, elaborate metaphor of sexual discovery in three books whose authors didn't put it there, or at least probably didn't deliberately put it there. Alice, for instance, tells the story of how her adult identity, and her fetish, began to form: As a girl, while being molested by an older friend of her family -- he had white hair and a pocket watch and spectacles and he was known as "Bunny" (of course he's the White Rabbit) -- she saw her reflection in a looking glass. That child, she imagined in that charged, hazy moment, was not just her older self but her true love, forever young and innocent. (And the suggestion is that she's attracted to actual younger women -- maybe children, maybe not -- because they remind her of that reflection.)

Moore has very often contextualized his comics within some kind of tradition, and "Lost Girls" devises, from a few scraps and hints, the idea of a legacy of pornographic fine art from the prewar era. In every room of the Himmelgarten, instead of a Bible, there's a white book of erotic tales and illustrations by famous decadent fin-du-siècle types like Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley (all, of course, pastiched by Moore and Gebbie). Gebbie's artwork is partly inspired by that era's artists even outside the pastiches -- her shapes and tones owe more to the ways early 20th century painters, especially Matisse, abstracted the human body than to the way most cartoonists do. She designs and decorates virtually every page with allusions to Art Nouveau; few comics artists care so much about wallpaper. Gebbie sometimes succumbs to the froufrou soft-focus eroticism of a David Hamilton photograph or an old "Emmanuelle" movie, but most of the time she avoids the clichés of both coy pastel "erotica" and clinical, sodium-lighted hardcore, and her sense of color and shade is unparalleled in comics.

So "Lost Girls" is shocking, it's lovely, it's ambitious, it's grandly clever -- but is it any good? Yes: It's very, very good, if flawed. Parts of it are some of the most extraordinary stuff Alan Moore has ever written; parts of it made me want to tear my own eyes out. (Some of them are the same parts.) Moore loads every line with thematic weight until it groans, his idea of what an American farm girl talks like is ridiculous, and the timeline is a mess: A few weeks' worth of events are spread out over a year, just so the narrative can encompass the May 1913 premiere of Stravinsky's "Le Sacre du Printemps," the June 1914 assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, and the subsequent outbreak of the Great War. Still, even some of Moore's stylistic tics work to his advantage here, like the elevated language he resorts to whenever he's got a point to make, with its da-dum da-dum iambic meter and lofty, elaborate diction ("An unseen hand undid my blouse, then moved inside and I sank gratefully into a fauve delirium; the drugging cherry warmth of her").

There's a lot of that high rhetoric here, because Moore's got an epistemological ax to grind. He wants to make very sure we get the difference between representation and reality, since he knows perfectly well that, as protectively fond as he is of Dorothy, Wendy and Alice, a lot of people are going to be extraordinarily unhappy about his setting them up with strap-ons and opium pipes. In one later scene, the Himmelgarten's unctuous manager Monsieur Rougeur explains that the fictions in the hotel's White Book "are uncontaminated by effect and consequence. Why, they are almost innocent. I, of course, am real, and since Helena, who I just fucked, is only thirteen, I am very guilty. Ah well, it cannot be helped." He's in the background of a sequence of panels as he delivers his monologue; the foreground is a series of close-up penetration shots, and the top half of the page is a scene of pedophilic incest, lovingly rendered in the style of the Marquis Franz von Bayros, with text pastiching Pierre Louÿs.

All of this is terribly uncomfortable to read; it's meant to be, obviously, because the argument is no fun if it's too easy. "Lost Girls" flirts openly with the idea of adults having sex with children, in everything from the premise of the book to its key sequences to Rougeur's coy admission of guilt as protestation of innocence. If there's a single sexual taboo that still pushes everyone's buttons, it's pedophilia. But one of the strongest effects art can have is a sort of inductive shock -- carrying you along someplace you don't want to go -- and as Moore and Gebbie underscore at every turn, no matter what their characters claim, what "Lost Girls" is showing isn't real. It's imaginary scenarios involving imaginary characters famous for their imaginations. The children's books about them haven't been violated; they're safe on the nursery bookshelf.

For that matter, if Moore and Gebbie have no time for prudes -- Wendy's husband, Harold Potter (whose name appeared in "Lost Girls'" early chapters long before J.K. Rowling finished her first book), a stuffy, frigid sort, is humiliated in a handful of rather-too-nasty, farcical scenes -- they've really got it in for adult molesters of children. Without giving anything away, a pivotal moment of each girl's story comes when the great and terrible authority figures who've taken advantage of their nascent sexuality are revealed as the tiny men behind the curtain they are.

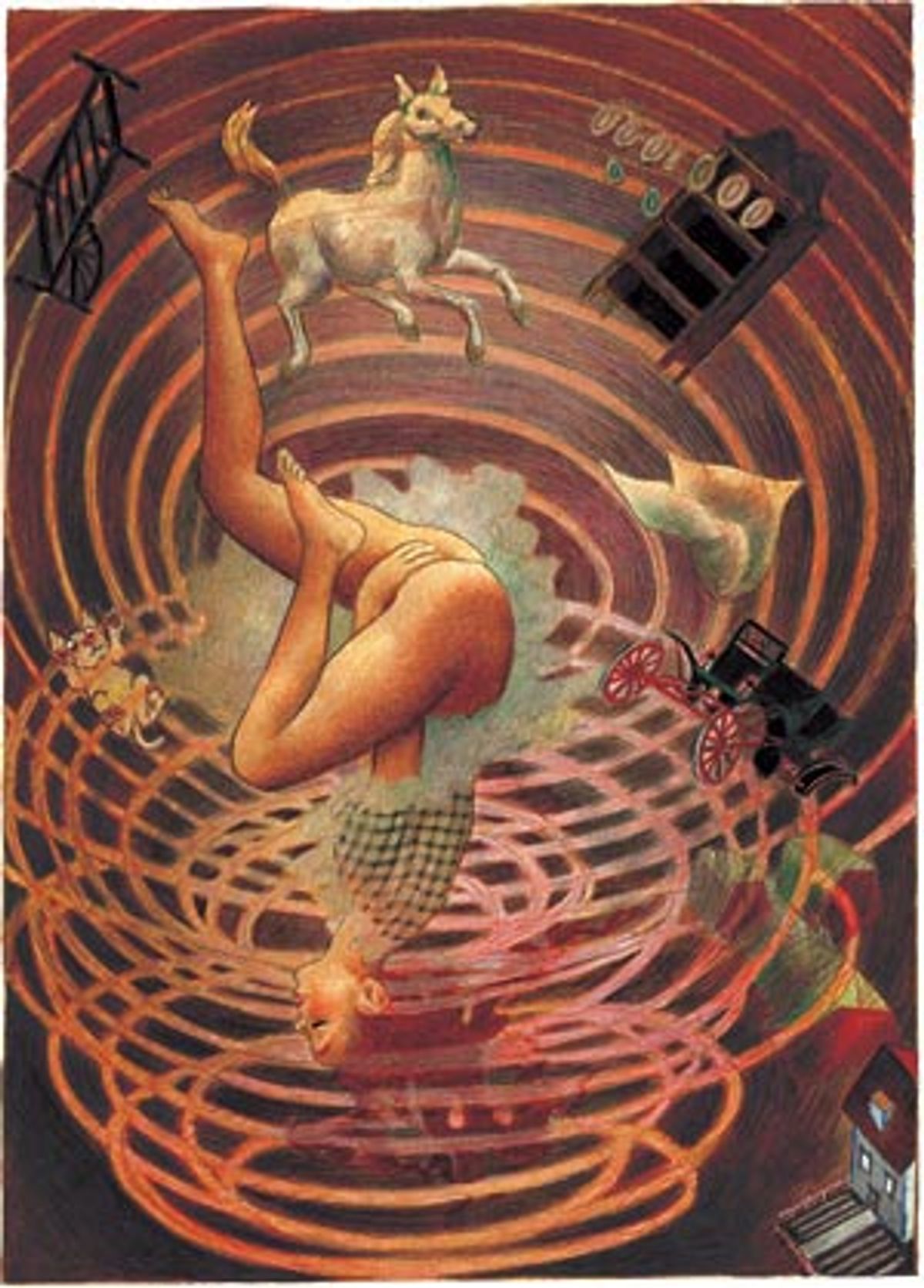

Moore has always been a formalist, from the clockwork structure of "Watchmen" to the Kabbala-map organization of "Promethea," but the structure of "Lost Girls" takes his formalism to the point of fetishism. (At least it's formally appropriate.) Each volume is named after a line from one of the source books, and contains 10 chapters, two of them devoted specifically to Wendy, two to Dorothy, two to Alice, and two including excerpts from the White Book. Each chapter has its own title and title page; each chapter in the second and third volumes in which one of the women tells her story includes one wordless full-page image directly inspired by a scene from that girl's original book.

More or less every other page in Vol. 1 has some kind of sexual content; that's ramped up to every page in Vol. 2, and practically every panel in Vol. 3 is flat-out hardcore. But by that final volume, the former child stars are fucking against the apocalypse. The war ("that which is most great, which is most terrible") is about to break out, the soldiers are off to the front, and there's nothing left for the hotel's remaining residents to do but lock the doors and screw themselves insensible until they have to run away.

The third volume is the roughest in more than explicitness: The characters enter the sort of pornotopian frenzy they've always imagined, and discover that coming back out of the sexual Wonderland is difficult and painful. The final sex scene is curiously feeble -- and it's followed not with any kind of afterglow, but with a sorrowful awakening into the world outside the boudoir, as the flames rise across Europe. Whatever awful realities come out of sex, Moore suggests, are a thousand times less awful than the violence that its energy can be perverted into.

The curious -- or curiousest -- thing about "Lost Girls" is that while it's enormously powerful and gorgeously executed, it's not actually all that sexy, or likely to inspire many fantasies on its own. The kind of release it offers is a fetishist's release: the sense that a ritual has been completed precisely. If it fails as smut, though, it's a victory as art, which is not a bad condolence prize. Like any number of boundary-pushing, button-pushing works before it, it may well require some kind of scandal, or at least a high-placed moralist's denunciation, to find the audience it deserves. It's spoiling for a fight, and it's worth fighting for.

Shares