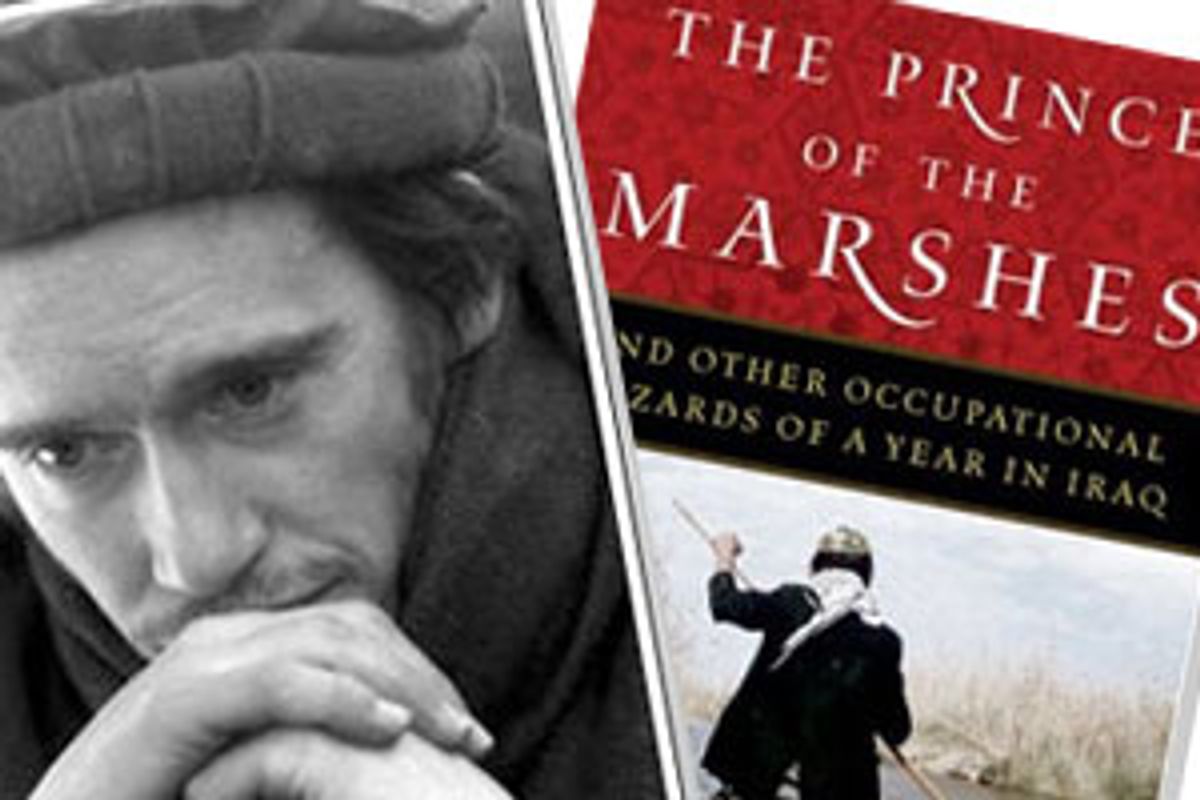

Rory Stewart rejects the label "pundit," but turn on the radio and there's a good chance you'll hear him commenting on the situation in Iraq. And not without reason. In 2003, having recently retired from Britain's Foreign Service, Stewart, 33, took a taxi from Jordan to Baghdad hoping to secure a job with the Coalition Provisional Authority and participate in the reconstruction of Iraq. Successful, he was assigned the governorship of Maysan Province, a remote, mostly Shia region of 850,000 people in the eastern part of the country. Yet, as the author of two highly praised books that tell the stories of two different war zones, Stewart could be mistaken for a renegade journalist who occasionally moonlights as a foreign aid worker instead of the other way around.

Just after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, Stewart walked 800 kilometers (or about 500 miles) across Afghanistan, from Herat to Kabul. The villages between the two cities, from the rich valley of the Hari Rud (river) to the mountainous Ghor region, gave him the name for his first book, "The Places in Between." Part traveler's journal, part history, the book traces Stewart's arduous journey, introducing us to Afghanistan's major ethnic groups and the often devastating conflicts among them. This strange walking tour of Afghanistan -- in winter, in wartime -- brings us to places so remote that villagers have never traveled more than a three-hour walk from their homes.

With his fluent Farsi and decade-long experience in the Muslim world, Stewart is an able guide. Other than noting his body's aches and pains, and describing his appreciation for the land, its quiet and his ability to walk ("I thought about evolutionary historians who argued that walking was a central part of what it meant to be human"), he rarely writes about himself. Instead, he focuses on the Afghan people and their lives -- from meals to mosques -- as well as their history. Amazingly, you never doubt his sanity for undertaking what is, in the end, a journey far more dangerous than most of us can imagine.

Stewart's second book, "The Prince of the Marshes," is another remarkably detailed account, this time relaying his year as a governor in Iraq. Stewart writes as much about the particularities of Iraqi greetings and the color of rationed juice as he does about the grittier details of war, like a chilling attack on the governor's compound -- an assault so brutal that it's shocking Stewart even survived.

"Marshes," more than anything else, is a civil servant's notebook, a kind of Westerner-caught-in-the-headlights how-to guide to running an occupation. As he writes, Stewart is well aware of the absurd situation he is in -- in his 10-month stint as governor he is expected, among other things, to create tens of thousands of jobs, rebuild hundreds of schools, organize a functional police force and oversee democratic elections, all while gradually handing responsibility to Iraqis, whose intentions he does not know. If there is one idea that runs throughout "Marshes," it is that foreigners -- who often know so little about the countries they are traveling to -- would do best to listen to and be as humble as possible toward the local people they encounter and must work with. Indeed, as a foreigner more often than not, this is what Stewart has spent the last 10 years of his life attempting.

I spoke with Stewart by phone from his home in Scotland as he was preparing to return to Kabul. We discussed why he thinks civil war is unlikely in Iraq, why corruption is sometimes necessary in democracy building, and how Afghanistan has changed in the last five years.

You've criticized the effectiveness of policy wonks and relief workers who spend just brief stints -- a couple of months at most -- in a country or region before moving on to the next one. You've made it a point to spend as much time as possible trying to understand local customs and societal structures in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

Well, I think that a necessary part of any kind of approach in a post-conflict society is to put a huge amount of effort into understanding local political structures. And that involves hundreds of hours spent asking hundreds of people about tribal structures, new political parties, people's biographies and histories. And, equally, a lot of time invested in understanding the manner or the politeness of a culture -- the way in which people greet each other, the way in which people sit in a room -- in order to sense what it is that can work politically, what is likely to engender a popular response, what's likely to offend people.

My guess is that the reason why a lot of international development work fails -- particularly in post-conflict situations -- is that security regulations prevent people from spending much time in rural communities or even interfacing directly with communities. Therefore development organizations like the United Nations, the coalition [Coalition Provisional Authority] -- tend to fall back on more abstract theoretical models which fail to take into account that it's the local, it's the particular, which defines the success or failure of an intervention.

Has there been a push to better understand local and political customs in Iraq?

Well, I think there's a lot more talk about it, but I think in practice it hasn't happened and it isn't likely to happen because our societies are so complacent, so isolated from the realities of rural life in the developing world that it doesn't seem to me credible that young American or British development workers are ever going to develop that kind of sensitivity and sympathy toward traditional structures. And development workers have a strong ideological reason to not want to get too involved in cultural systems because they would perceive this as much too political, even, in their mind, colonial. They would prefer to see development work as a very impartial, neutral economic process and they are uncomfortable with the whole business of engaging with local political structures.

So there's a guilt factor.

Yes, there's a very strong guilt factor. There's a very strong guilt factor that underlies any kind of attempt by foreigners to intervene in somebody else's society.

And yet when it comes to something like drafting the constitution, arguably the fabric of a society, there are these foreign law professors and academics coming in to offer expertise. Is that not perceived as colonial?

Well, for some reason those kinds of things are framed as though they're abstract and universal. Somehow, at least in a certain academic vision, constitutions and democracy have been viewed as a technocratic exercise based on the assumption that all humans, in terms of their rights and legal structures, are the same. That there's a single thing called democracy and the rule of law. And that you can bring it to somebody else's country.

And can you? Does that ever work?

Well, it works well if you're setting up a central bank or stabilizing the currency. It does appear that foreigners can do those kinds of things relatively easily. Which implies to me that these are relatively technocratic, value-neutral interventions. But I think that drafting constitutions and human rights laws turns out to be considerably more culturally inflected and controversial than we acknowledge.

If you could generalize, what are the primary needs of Iraqis, let's say in Maysan Province, right now?

Well, in somewhere like Maysan I think people would talk firstly about security. And they are very disturbed both by the continuing level of criminality and by the militia groups which answer to the elected politicians and which still continue to intimidate and occasionally kill citizens on the streets openly with impunity. They're also obviously very worried about terrorism and by the number of people who are being killed by bombs or dragged from their cars and shot on the major highways. People are barely visiting Baghdad at the moment because they see the highways being too dangerous and Baghdad itself as being too dangerous. So, security first.

Then I think they would worry a great deal about what they see as corruption and injustice in government. A collapse in moral standards, a return to tribalism, immorality in general, lack of economic progress.

So not so much gender equality.

Well, of course for women that's a very serious issue. Particularly for educated women from more middle-class backgrounds. They feel that the departure of Saddam has led to a very serious decline in the state of the women, that they were much freer in terms of their social codes and their dress and their behavior under Saddam than they are now under a more Islamist government.

You mentioned corruption being one of the main concerns. However, right before the Maysan elections it becomes clear that one of the more extremist, Islamist groups is probably going to win. And there's an instance, which you discuss in the book, where you realize that in order for the more moderate group to have a chance they need more funds. So you decided to give them money from the CPA bank, essentially allowing the CPA to intervene in the fate of the election. Can you explain your decision to give this group money, which could be perceived as quite contrary to the democratic values the West is trying to build.

I think it was a very difficult decision that I made there and it's still not a decision that I'm entirely comfortable with. But my sense is that the extremist groups, the Islamist groups who hated the coalition, who wished to impose extremely conservative, oppressive codes, who were supported by violent, armed militias, were dominating the province partly because they were the only parties with access to funds. They were funded by the Iranian state covertly and by Syrians covertly and even by independent businessmen from other parts of the Middle East.

The moderate Islamic groups had a much more tolerant, pluralistic vision of Islam and a much more pragmatic and cooperative attitude toward the international community. They were not supported by violent armed militia groups and therefore resembled more closely the kind of democratic society that we were trying to establish, but received no funding or support at all. So the extreme Islamist groups could hire entire rioting crowds of 3,000 or 4,000 people and pay them, and the moderate groups were unable to rent a tea boy and communicate their message.

So my sense was that providing a small amount of funding to new political parties with moderate, human rights-friendly agendas was necessary in terms of the creation of a pluralistic democracy.

You've said that you don't see the likelihood of civil war in Iraq -- even if, or when, the U.S. troops eventually withdraw. But at many times throughout "Prince of the Marshes" you highlight major divisions among Iraqis -- even from province to province or town to town there will be an "official council" and then an "alternative council." And there's a perception in the U.S. that, if anything, civil war has already broken out.

In 2003-2004 I thought civil war was very likely. Not civil war in the sense of two huge factions fighting each other up and down the country, but a collapse of authority and a disparate group of local and tribal militias and parties squabbling and fighting it out town by town. That changed at the end of 2004 and by the elections of 2005. I know in southern Iraq, basically, the government has authority and keeps control, and the only two groups really squabbling outside the law are the armed militias of the Sadrist party and the Badr Brigades, which are the two big elected parties.

I think those militia groups are kept mostly under control by their political leadership and I think those political groups have proven again and again a real ability to negotiate compromises and find resolutions -- even with their Sunni opponents. Most Iraqis I know -- in fact all Iraqis I know, who are Iraqi Arabs as opposed to Kurds -- have a strong sense of being an Iraqi, which trumps their sectarian divide. Therefore, my intuition is that were we to withdraw, rather than collapsing into a terminal civil war between Sunni and Shia factions, Iraqi society and Iraqi politicians would be able, relatively rapidly, to reestablish control and a unitary nation with an exception of the Kurdish area.

Do you think there will eventually be an independent Kurdish state?

I think the Kurds probably will eventually press for greater and greater autonomy and perhaps eventually independence, yeah.

You've been calling for troop withdrawal.

I think first of all one has to negotiate very strongly with the Iraqi government to make them understand why we're doing this, to get their full support for this decision. And that's not going to be easy because at the moment a lot of the Shia politicians are nervous and perceive us as the only thing that stands between them and anarchy. So we need to develop their sense of self-confidence and autonomy. And then we need to immediately draw troops back into bases and limit the number of operations they undertake to allow these areas to settle themselves. And to accept the fact that often the way these areas settle will be far from ideal.

In Southern Iraq -- that's the model I'm following here -- there are very few troops outside their bases. They are not patrolling very much, they are not intervening much in the political process, and what's actually happened is quite an authoritarian government has reasserted control -- but it's an Iraqi government. And that's probably what will happen in the rest of the country, and we'll have to accept that in Fallujah and Ramadiyah and Tikrit that will include the consolidation of power by Baathist groups or even anti-foreign insurgent terrorists.

So this is a very unpleasant, difficult decision to make, and it's very much a decision which is choosing the lesser of two evils. I'm not trying to whitewash; I'm not trying to say this is going to be an easy, attractive option. I'm just trying to say that of all the options available it's the least bad one. I don't believe there is any sustainable, credible future in keeping the coalition there simply to keep the lid on a society and a political process which is fundamentally at odds with the vision of the coalition. And then eventually that needs to be followed by complete troop withdrawal.

You've talked about how invading and occupying Afghanistan was much easier in many ways because Afghans were already living in desperate conditions before the invasion, whereas in Iraq, in many instances, things have become worse. Have you noticed considerable improvement in Afghanistan in the last few years?

Yes, I think I have, particularly in the central and north of the country. If you're a Hazara the departure of the Taliban has led in the first place to a massive increase in your own security. I walked for four days to villages that had been burned to the ground, places like Yakawlang where 400 villagers had been executed against the village wall. For those people the removal of the Taliban has been a great improvement because their own ethnic group is now in charge of administering their own ethnic areas and their government is more humane, more just, and delivering more prosperity than what was available under the Taliban.

The economy is growing by 18 percent a year, there is no civil war in Kabul nor is there an extremist conservative religious government executing people in the main stadium. So I think things have improved in Afghanistan. But of course it's still a very poor, fragile, traumatized country. And as people point out, there are warlords and there is drug growing and the Taliban is resurgent in the South. On the balance, yes, a great improvement, but far from perfection.

It's astonishing that you weren't killed, or didn't die in a snow drift, on your walk across the country. What inspired you to make that walk just after the invasion, in the dead of winter?

I'm very, very bad at answering that question. To some extent I'm fascinated by countries emerging from warfare. I'm particularly interested by a country as remote and detached from the region as Afghanistan was in 2001. Villages where there was no electricity, where people had never been a three-hour walk from their village in their life, are increasingly unusual in the modern world and seem to reveal a great deal not just about Afghanistan but about human society. So what started as a walk really concerned with landscape and physical adventure became increasingly an opportunity to study societies, to study village life, to have the privilege of sleeping every night in a different village house.

Many of the villages in Afghanistan were so remote that people had little concept of the World Trade Center or why the U.S. was bombing the country in the first place. And yet you were never turned away by anti-Western sentiment; it is frankly surprising how well you were treated in the villages.

With incredible kindness! The hospitality and dignity and generosity of my hosts was extraordinary. They basically passed me like a parcel across Afghanistan. I made it alive because they wanted me to live. It's a real revelation how even a society which has been through 25 years of war with no government, no police, no justice systems or rule of law can still operate with such restraint and generosity and actually maintain a real level of security.

You'll be returning to Afghanistan on Friday.

I will be there for most of the next couple of years. I run a foundation called the Turquoise Mountain Foundation and we're working to help the community restore part of the old city of Kabul and we're training Afghan craftsmen in woodwork, ceramics, calligraphy, illumination, masonry, and supporting Afghan craft businesses and export. We're hoping to combine an investment in Afghanistan's traditional culture with delivering real economic opportunities for living Afghans.

And will you be going on more walks when you're over there?

[Laughs] I will spend most of my time walking around the old city six, seven hours a day. But that's because our project is to some extent a building project.

And the Turquoise Mountain, that's named after --

It's a lost ancient city in the central Ghor region of Afghanistan.

Just after the invasion there was massive looting of the ancient city, which was later named a "world heritage site." It seemed that the West had very little interest in making it a priority to stop the looting.

It's something I pushed for at the time very strongly and was really surprised by the lack of interest or engagement by UNESCO [the U.N. body responsible for cultural heritage]. I think Western governments tend not to think in terms of history and culture. They tend, in these emergency situations, to focus on issues like health and education and it's very difficult to get people interested in issues, which I think in the long term, often prove to be very central to how a country like Afghanistan rebuilds its identity and views itself in its own history. The tragedy of the looting of the Turquoise Mountain is that this stuff is gone and gone forever in an instant.

Shares