We have suspected for more than 15 years that North Korea has separated plutonium from nuclear reactor fuel for use as the core of a nuclear bomb. If the test there on Monday of a nuclear device proves to be authentic, North Korean scientists will have demonstrated that they have designed an explosive casing that can compress plutonium to critical mass, triggering an explosion. North Korea will have become the world's ninth nuclear-armed state.

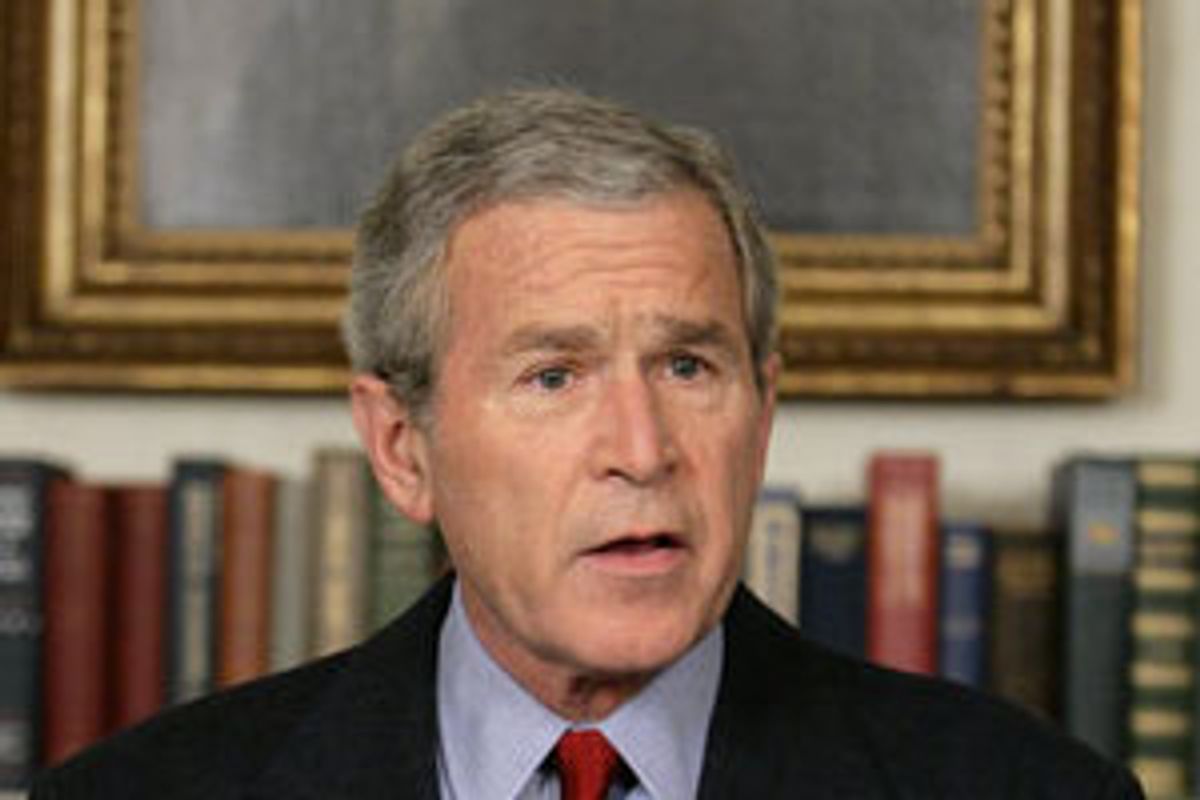

The Bush administration appears divided over how to respond. Yet, despite some internal dissent, hard-liners in the administration have controlled the U.S. approach to North Korea since Bush took office. That approach has brimmed with tough talk and threats, while scorning diplomacy as a badge of weakness. The White House refuses to negotiate directly with North Korea -- but it has no viable plan, military or otherwise, for stopping further tests. North Korea's provocative move is the latest evidence that Bush's strategy for preventing the global spread of nuclear weapons has failed.

The greatest danger is not that North Korea would attack us or our allies with this new capability, or even that they would provide a nuclear weapon to terrorists. Kim Jong Il would know that the response to the use of a North Korean bomb by him or his surrogates would end his life, his regime and a good part of his country. The greatest danger is what happens next in the region -- and the specter of a new arms race that could fast spiral out of control.

South Korea and Taiwan had nuclear weapon programs they ended only under U.S. pressure in the early 1970s. In fact, South Korean scientists, we now know, were still conducting secret nuclear experiments in the 1970s, 1980s, and as recently as 2000. Surely North Korea's latest move has at least some in South Korea and Taiwan thinking about restarting their programs.

Japan, also in range of North Korean weapons, may be even closer to a flash point. Shinzo Abe, the new, rightist prime minister of Japan, will certainly use the test to push for a more assertive Japanese military, and the strong antinuclear sentiment held by the Japanese public could evaporate. Japan has separated more than 23 tons of weapons-usable plutonium from reactor fuel and could have a nuclear arsenal within a few months of a decision to do so.

The fallout from an escalating arms race in the region could quickly spread across Asia. In India, where officials conducted five nuclear tests in 1998, scientists could push to test again. Pakistan could follow. The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty would be left in tatters.

Iran, another top target of the Bush administration, is watching closely. If North Korea gets away without punishment, the Iranian government will likely accelerate its "peaceful" nuclear program, which it claims is only for use as a source of energy. With the technology it has, Iran is five to 10 years away from the ability to make nuclear weapon material -- but it will be much more difficult to limit the Iranian program in the wake of an accepted nuclear North Korea.

How did we get to this dismal point? The divide over North Korea, and indeed Bush's entire approach to proliferation, has existed from the administration's first days. On March 6, 2001, Secretary of State Colin Powell said he "would pick up where President Clinton left off" with North Korea -- negotiations that had frozen for years both plutonium production and missile tests. The very next day President Bush cut Powell down, saying that any negotiations in his administration would have a "different tone" from those of his predecessor. Thus began the redefinition of diplomacy, from a process involving give-and-take to a policy of trying to coerce our adversaries into submission.

The Iraq war was the first implementation of this new approach to proliferation -- one that explicitly aimed to eliminate regimes. Ostensibly, the war was intended to both remove Saddam Hussein and show other states the heavy price they would pay for pursuing weapons programs the United States opposed. When then-Under Secretary of State John Bolton was asked what lesson Iran and North Korea should draw from the war, he said, "Take a number."

But the strategy has backfired miserably. Each member of the "Axis of Evil" is more dangerous to America today than when Bush labeled the group in January 2002. Iraq had no nuclear weapons, but it has been plunged into chaos and become a breeding ground for terrorists. Iran has advanced more in its nuclear program in the past five years than it did in the previous 10. North Korea ended its freeze and increased its estimated supply of plutonium from enough for two weapons to enough for perhaps 12. If it reprocesses another load of reactor fuel, as it recently threatened, the stockpile goes up by another five or six. If it continues its tests, it could perfect the design and shrink the package to one that a plane or medium-range missile could carry.

We must recognize Bush's utterly failed policy and reverse course by putting diplomacy back at the center of our strategy. We can no longer afford the split between realists in the administration, like Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Assistant Secretary Christopher Hill, who want to negotiate with North Korea (and Iran), and the ideologues, led by Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, who want to overthrow both regimes. Hill negotiated a deal to end the North Korean program last September -- only to have it torpedoed by sanctions imposed under Cheney's direction. The sanctions hurt enough to infuriate the North Koreans but not enough to force them to capitulate. The deal collapsed.

The new United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki Moon, could help change the dynamic swiftly and dramatically. A South Korean, he has offered to mediate, and he may be ideally positioned to do so. He might offer to visit Pyongyang as long as there are no further tests. China could play a key role in negotiating this arrangement -- and could apply its own pressure. China will never squeeze North Korea hard enough to force a collapse of the Kim regime; that would send millions of refugees streaming north and south. But China has shown it will press North Korea to come to the table -- if China knows that the United States is committed to real bargaining and not just blustering.

This time President Bush must tell Cheney and Rumsfeld to back off. He must end the misguided diversions of John Bolton, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, a man whose pompous proposals have encouraged proliferation, not stopped it. Bush must free negotiators to follow the Libya model, where we change a regime's behavior, not the regime.

The 2003 Libya deal, hinging on negotiations, cost us little in funding, nothing in lives, and was 100 percent effective in ending that nuclear program and reintegrating Libya into the world community. Even if such an effort fails with North Korea, we will have kept faith with our allies and laid the groundwork for an effective containment strategy, one that could isolate North Korea and possibly prevent the chain reaction of nuclear proliferation.

It is time to restore some realism to America's relations with foreign powers -- including our enemies -- and to back our negotiators with the full range of American military, political and economic power. We have to take our national security policy back from the ideologues and speechwriters, have faith in our diplomats, and let them complete the job they have been aching to do for six long years.

Shares