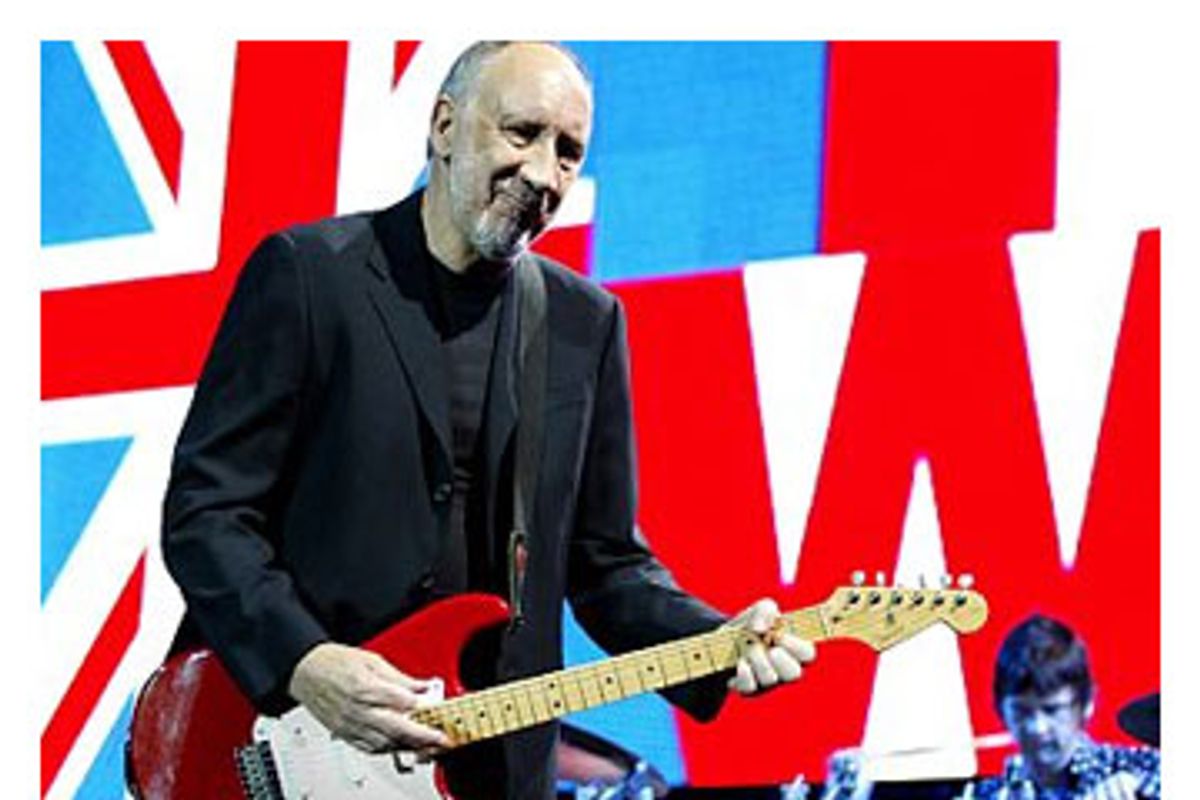

Power chords, rock opera, guitar smashing: Pete Townshend is the man to thank for all of them. As the main songwriter, guitarist and all-around driving force behind legendary rock band the Who, Townshend has contributed as much as anyone to the development of rock 'n' roll, from long-form narrative works like "Tommy" and "Quadrophenia" to three-minute bursts of adolescent angst like "My Generation."

"Endless Wire," released on Oct. 31, is the first album of all-new material to bear the Who's imprimatur in almost a quarter-century. Half devoted to thunderous rock songs and quieter, emotionally astute numbers and half given over to a dystopian "mini-opera" called "Wire & Glass," the album shows Townshend and lead singer Roger Daltrey working with a vigor and vitality that won't disappoint longtime fans, despite the absence of longtime bassist John Entwistle -- who died in 2002 -- and long-deceased drummer Keith Moon.

Currently on tour with the band, Townshend, 61, is giving only e-mail interviews. (Last month, he walked out of a planned radio interview with Howard Stern after Stern's sidekicks began joking about his 2003 arrest for child pornography. He was arrested for making a single access to a child porn site, which he claimed was for research for a book he was working on, and police later dropped all charges against him.) In his e-mail response to Salon, he wrote about his commitment to using pop songs as a vehicle for his larger ideas, how the Who fit into the current pop culture landscape and whether, in the light of his own troubles, the Mark Foley scandal had any effect on his thinking about the merits of online communication.

The new album shows that you're still committed to the idea that pop songs can be used to tell a complex narrative tale. What is it about pop music that you think provides such fertile ground for long-form storytelling?

It works for me in input mode; in other words it helps me focus and generate fresh approaches to old ideas. I'm not sure it always works in output mode, when it lands in front of you as pop music. Usually a pop song is like a child's fairy story -- it is something small and light that might well carry a very adult and serious idea. I often like the idea of a pop song that has a single function as a part of a wider brief.

How did the fact that this was a Who project affect your songwriting process?

I have never written for the Who -- I've just written. What happened here, after many years of waiting, albeit hopefully, was that suddenly I had a collection of songs I felt would indeed work as a Who album. Once that decision was made, to collect these particular songs for a Who project, I presented them to Roger -- now the only person I have to involve at an early stage -- and he began his business of rubber-stamping certain songs, or asking for minor changes, or making editorial comments. It's an enjoyable creative place to be back to after so many years of working alone.

Your own history has shown that the accessibility and openness of information and content on the Web can be a dangerous thing. Yet at the same time your work seems to hold a hopeful attitude toward the Internet. Do you have any ambivalence about the Internet?

I have no ambivalence. I am very clear that the Internet is a mirror of society and will reflect both extreme good and extreme bad. It is legally almost unpoliceable at "input," so it is vital that we don't allow shame or political correctness to prevent us from commenting when we find something shocking for fear of being punished (as I was) as a receiver. I think that as with society as a whole, the good far outweighs the bad. We mainly focus on the bad news, and there are billions of us in society who do not exploit the vulnerable, steal, rape, abuse or murder. There are as many who find time to spread positive ideas in our blogs rather than hate and bile. I think we do OK.

The narrative of the "Wire & Glass" mini-opera seems difficult to follow without being exposed to the online novella it was originally conceived as being a part of. Why offer listeners a "part" (the music) when they may not even realize a "whole" (the novella plus the music) exists?

There is no need for perfectly plotted narrative in pop music. The story that supports the music is the story and experience of the listener. Yes, if anyone really wants my version of the story they can go to my Web site and check it out. Beware, it may spoil the music for you. However, it may enrich your enjoyment of it -- it depends what you want your music to do. "Quadrophenia" was the story of a boy who had a very bad day, went out to a rock at sea and it rained. I've had people tell me it changed their life. Something was at work that was not the narrative. "Wire & Glass" is similar. Three kids form a band and take up where an old rock star gave up. They also give up, but it's a great ride.

Do rock and pop mean different things to you know than they did at the time of the last Who album 24 years ago? If so, what has changed?

It is still the same, amazingly. It is music with a clear function. But so was the music that came before the late 50s. My father's swing music was meant to soothe and encourage optimism and the possibility of postwar romance. My music is meant to confront trouble and pain, and through union and sharing (congregation) allow us to "dance" to a solution. I feel my music would be less valuable if there was a real world war. We would need different music then, maybe more like the music my father used to play.

Does working within the machinery of the Who feel cumbersome or stifling? Do the benefits outweigh the disadvantages?

It is cumbersome, but there are pros and cons of course. Yes, I think it has great value. How would I reach so many people with something like "Wire & Glass" without using the Who banner? I'd need to stage a big Vegas show, or do a very ambitious movie. This rock tour, rock CD thing, still works for me very well. I'm delighted to be here. It's also something I happen to be extremely good at and find easy to do.

The non-opera half of the new album features some of the simplest and most direct music of your career. Was that intended as a counterweight to the more musically complex and conceptually dense material?

Not consciously, but maybe when I came to sequence the songs I chose songs that counterbalanced the density of the mini-opera. I also think I'm trying hard to keep my songwriting direct today; I'm pleased you see it that way. By that I mean I want each song to have the potential to touch a certain listener deeply enough that it can work for them uniquely.

I exalt the audience, as you may know. I feel lucky as an artist to have a commission of sorts from the audience to write music they can perhaps use in their everyday lives. Whether it simply helps them on their way to work in their car (like "It's Not Enough") or challenges the assumed authority of their demagogic leaders (like "Man in a Purple Dress"), every song must have its potential to be adopted into the listener's life for me to feel I've done a good job. Not everyone means the same thing when they repeat "Meet the new boss, same as the old boss" or "I hope I die before I get old," but as long as the words are useful I feel vindicated as a writer.

Given that rock 'n' roll no longer holds the place in the culture that it did when the Who were at the peak of their popularity, where do you think your work fits in the contemporary musical landscape?

I don't worry too much about the mass audience. I focus on an extremely polarized group of music fans, and as I said, I feel lucky to have them because although their consumption of music may be narrow, their expectation of what it might do for them in their daily lives is vast.

In the light of both your own experiences and the recent Mark Foley scandal, why do you think it is that our society so swiftly moves to a state of near hysteria anytime the issue of children and sexuality comes up? Has it changed your thinking about the subject? Were you perhaps naive?

I saw myself as an Internet whistle-blower and it went very wrong for me. I keep away from stories that might reignite my anger. As I said earlier, the Internet is not entirely evil by any means. In daily life I still work to fund the counseling of adult survivors of childhood abuse, including sexual abuse. I find this work sublimely uplifting, but sadly not always successful. It is human nature to want to protect our young from the mentally sick.

What would you tell the Pete Townshend of 40 years ago? What would he say to you today?

This is a staple part of a 12-week workshop in a book called "The Artist's Way." So I did this a while ago when trying to find a way to get past a perceived "block" while in fact I was still very prolific. I think in my letter to young Pete I told myself that I shouldn't worry. There would be no nuclear holocaust. The planet would not become so polluted that we would all have to live in suits like they do in "Dune." I think young Pete told this old fart to mind my own business. I think he was right.

Shares