On Monday, Illinois Sen. Barack Obama told a home-state audience how the Democrats would use their new power in the House and Senate to help deliver the United States out of the wilderness in Iraq. In a speech to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs titled "A Way Forward in Iraq," Obama called for "a phased redeployment of U.S. troops from Iraq on a timetable that would begin in four to six months."

"Redeployment" is fast becoming the rallying cry for Democrats, who have new power in Congress and are getting fresh attention from the media. Obama was echoing several prominent Democrats who floated the word in last week's electoral afterglow, including new Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid but starting with Sen. Carl Levin.

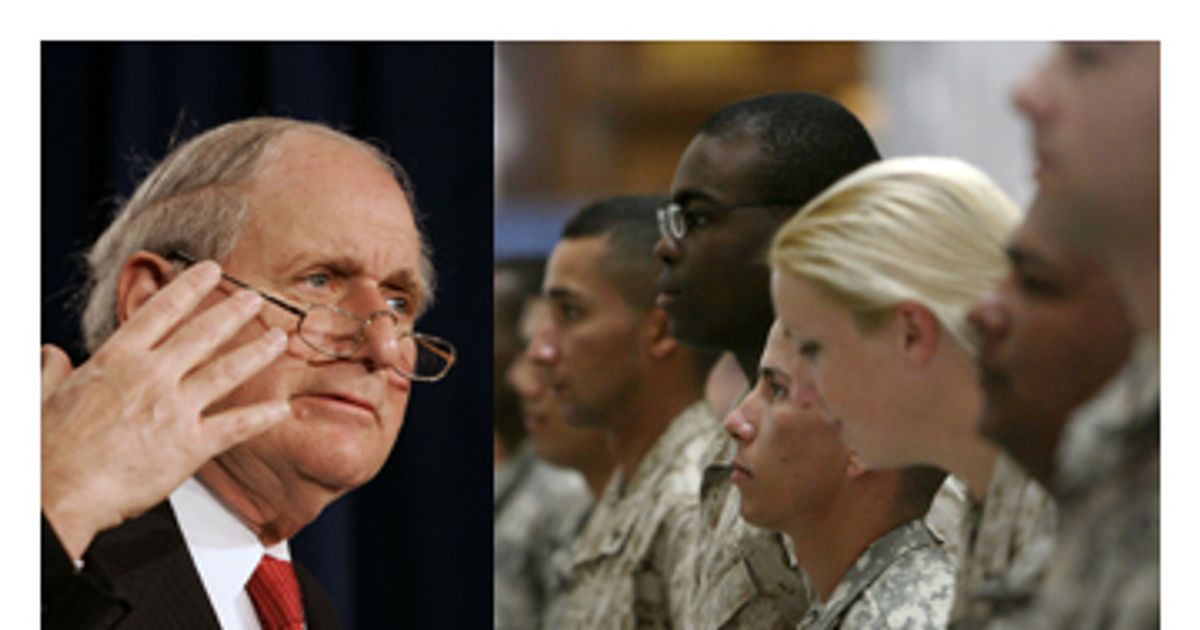

At a standing-room-only press conference in the Senate Radio-Television Gallery last Monday, Levin announced his priorities as incoming chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. "The first priority would be to find a way forward to change the course in Iraq," Levin said. "Most Democrats share the view that we should pressure the White House to commence the phased redeployment of U.S. troops from Iraq in four to six months." Levin told reporters that the centerpiece of the Democrats' plan for Iraq was to pass a resolution to start getting out of that war-torn country within half a year.

Democrats have seized on what they say is a mandate from the public to alter the strategy in Iraq, mixing tough talk with promises of action -- of "redeployment." But if the voters who gave them control of both houses of Congress think a real change in policy is imminent, early signs suggest that the Democrats won't be delivering very much very soon. The proposal that Levin outlined remains vague, is modeled on an earlier proposal that failed, and leaves key decisions in the hands of President Bush. With their slim majority in the Senate, the Democrats may not have the votes to force a radical change in direction, and have limited powers to accomplish that goal anyway. The Democrats' current approach, some political experts say, seems to be aimed at keeping Bush saddled with the Iraq problem, and forcing him to be the one who loses the war.

What the Democrats are advancing is a "non-binding resolution." It is an articulation of majority opinion in Congress, but it carries no real legal weight. Second, while the plan may call for a "phased redeployment" of troops, Levin told reporters that the resolution would not specify what redeployment really means -- whether one soldier would come home in the next four to six months or 50,000 would be boarding planes. That would be left to the White House.

There is nothing on paper yet, but Levin said the proposal might be similar to a resolution he tried to push through the Senate in June that called for the "phased redeployment of United States forces from Iraq this year." It was defeated in a 60-39 vote. Six Democrats voted against it -- Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, Bill Nelson of Florida, Ben Nelson of Nebraska, Mark Dayton of Minnesota, Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut, and Mark Pryor of Arkansas. Dayton has been replaced by a different Democrat, and Bill Nelson appeared with Levin at his press conference, but Levin will still need new Democratic votes -- and, almost certainly, some GOP support, to pass the resolution.

And Democrats have been sketchy on whether they will try to force through the resolution at all when they do take over Congress next year. Instead, they want to see what other alternatives present themselves first. Levin said Democrats want to hear about ideas on Iraq from the Iraq Study Group led by former Secretary of State James Baker. Democrats also want the results of an internal, ongoing Pentagon strategy "scrub," or policy review, that is supposed to generate some new notions as well. (The Washington Post reported Monday that the closely guarded "scrub" has boiled down to three options: sending more troops, reducing the size of the force but planning to stay longer, or pulling out.)

The truly cautious nature of the Democratic approach became apparent in a chat Levin had with a bevy of reporters after his press conference, when the TV cameras had been turned off. Levin seemed to admit that the focus of the proposal was not to get a substantial number of U.S. troops out of Iraq quickly. Instead, Levin said it was more important that the Iraqi government get the "message" that the U.S. might begin to leave Iraq sometime soon. Faced with the prospect of a full-fledged civil war likely to follow a U.S. withdrawal, the threat of that redeployment might force the Iraqis to cut a political deal to save the country from the abyss.

The goal, Levin said, was to put "pressure" on the Iraqis. "What they need to hear and what the American people need to hear is that we are darned impatient," he explained. In other words, the resolution is more of a suggestion to the president that he threaten the Iraqis with a withdrawal, rather than a push for a significant withdrawal anytime soon.

Obama emphasized that message when he reiterated the Democrats' plan on Monday. "I have long said that the only solution in Iraq is a political one," he said. He argued that the United States must "communicate clearly and effectively to the factions in Iraq that the days of asking, urging and waiting for them to take control of their own country are coming to an end."

Obama also tried to establish a degree of separation between his party and any real action on the ground in Iraq, noting that the president should take the lead, the military should help decide how many troops should leave and when, and the timetable for the plan should not be "overly rigid."

"The president should announce to the Iraqi people that our policy will include a gradual and substantial reduction in U.S. forces," Obama insisted. "He should then work with our military commanders to map out the best plan for such a redeployment and determine the precise levels and dates."

The cautious Democratic approach is partly based on cold mathematical and legislative reality. Given their razor-thin majority in the Senate, it is unlikely that the Democrats could pass through Congress anything more than a non-binding statement. "The non-binding resolution is a proposal that the president admit that he had been wrong," explained David Rohde, a professor of political science at Duke University. "Trying to impose that on the president given the numerical balance of Congress is not possible." And there are few instruments Congress can use to force a change even if one could be agreed on by both parties, since tactical control over the war rests in the hands of the president. Democrats could cut funding for the war and thus force a pullout, but they've already admitted they have little appetite for that gambit.

Not only is there a limited amount that Democrats can do, political experts said Democrats don't necessarily want to do much either. The war in Iraq runs the obvious risk of becoming a total failure, and Democrats, long called weak on defense by their Republican opponents, don't want to be the party that "lost the war" come future elections. Through a non-binding suggestion, Democrats leave the real decision-making up to the president -- and the black mark goes on his record if and when the United States officially loses.

"Basically, what they are saying is lay down a marker, but put all the substance in the hands of the president," remarked Douglas Foyle, a political science professor at Wesleyan University. "I think it is politics." Foyle said polls show that 60 percent of Americans are in favor of "some level of troop reductions. This is the Democrats running with that sentiment and taking political advantage." Added Duke's Rohde, "Like any other politician, the members would like to achieve their objectives without potentially taking the blame for it."

And by keeping their position on what to do in Iraq both aggressive-sounding but ambiguous, Democrats hope to maintain the political momentum they generated during the elections without much risk of making the wrong policy choice. "They basically ran on a platform of change, saying, 'We are going to be different.' But they were very vague on what 'different' was," explained Christopher Gelpi, another political science professor at Duke. "So they are wary of boxing themselves in. They do nothing but hurt themselves by making a commitment now."

"Politically it is a pretty astute policy," noted Foyle. "There is a question of whether they can pull it off."

Shares