He was dressed all in fur from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot.

There is no Santa Claus. Not in the poem now known as "The Night Before Christmas" published anonymously in 1823 and credited to Clement Clarke Moore, whose verses feature a weirdly elvish figure named St. Nicholas. Not in Charles Dickens' 1842 "Christmas Carol," with all its sanctimonious sermonizing about Tiny Tim and the true meaning of Christmas. For all practical purposes, there is no Santa Claus before 1862, the year that Rowland H. Macy took the gift-giving gnome known around New York as Sinterklaas (from the Dutch "Sint Nicolaas"), used an Anglicized name, had him impersonated by a reassuringly full-size human, costumed him in a nice, clean cloak, and installed him in the store as a means of snaring more Christmas shoppers.

True, there was St. Nicholas, an early Catholic saint from Asia Minor who went on to become the all-purpose patron of Greece, Russia, children, spinsters, brides and workers ranging from bootblack to brewer. Old Nick had survived the Reformation by ingratiating himself with prosperous Protestants as an unthreateningly unclerical dispenser of presents and punisher of naughtiness. But by the time Washington Irving, writing as the pseudonymous Diedrich Knickerbocker, put him in the fictional 1809 "History of New York," the Dutch settlers' St. Nicholas had shrunk to a small folkloric figure wholly without canonical clout.

That St. Nick, however, was still a long way from Santa. In 1841, Philadelphia store owner J.W. Parkinson hired someone to pose as St. Nicholas climbing the store's chimney, thus becoming the first retailer on record to sense the sales potential of Moore's much-published poem. (Though decades ahead of Macy, Parkinson unfortunately missed Macy's insight that the payoff comes from luring shoppers inside a store.) During the 1860s, Bavarian-born illustrator and war correspondent Thomas Nast featured Moore's version of St. Nick in a popular series of woodcuts made for Harper's Weekly. But Nast, who gave America its Republican elephant, Democratic donkey, and Uncle Sam, followed the verse descriptions and depicted a pot-bellied fairy figure wearing a tight fur jumpsuit and smoking a long clay pipe.

It took another German immigrant, Louis Prang, to Americanize the appearance of the character who, thanks in part to his annual appearance at Macy's, was fast becoming more famous as Santa Claus. Though stationers had started the custom of sending Christmas cards well before the Civil War, Prang, a chromolithographer, recognized the money to be made from postwar improvements in the U.S. postal system. Alongside his season's greetings showing bonny tykes frolicking in the snow and darling kittens sitting down to the dinner table, Prang came up with a Santa Claus so cute, so cheery, so chubby and charming, that it set the standard forever after. Santa was now identifiable by his white beard, his colorful red coat, his stocking hat, and his sturdy belt and boots. Trimmed in tasteful winter ermine, unsoiled by ashes and soot, the reformed goblin was now well-suited for welcome into middle-class Victorian households. Nast stuck close to the original and died more or less broke. Prang sanitized Santa and died a rich man.

A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a peddler just opening his pack.

Today, Macy's remains Santa's longest-running gig. "Macy's has postcards showing Santa in the 1870s: In one, Santa is coming down the chimney wearing a red suit without fur and carrying a white bag with the Macy's star on it," says Bob Rutan, director of event operations and thus the man in charge of readying Santa for this year's 144th round of in-store appearances as well as his TV time as grand marshal of the annual Thanksgiving Day Parade.

At Macy's, Santa Claus sticks to two versions of the same suit, which is a 7/8 coat worn over matching pants cut extra-roomy (so that hundreds of thousands of kids can perch comfortably on his knee and tell him what they want for Christmas) that stay on Santa by means of a bib front and straps (a modification made decades ago when a little girl tugging on Santa's pants tugged them off on national television). On Parade Day and on Christmas Eve, when he comes prepared to fly out of the store at the stroke of 6 p.m., Santa wears what is known as the "flight suit." It's trimmed with real rabbit fur, comes with a coordinated quilted cotton greatcoat and weighs about 40 pounds. For everyday duties in Santaland, where he saw 238,000 Macy's shoppers last year, his costume is a fake fur-trimmed wool twill that weighs around 18 pounds.

Because no one wants to sit on the knee of a smelly, sweaty Santa and because quite a bit of body heat builds up when the line snaking through Macy's eighth-floor maze hits 500 or more on a holiday weekend, Santaland got its own air conditioning system in 1998. Even so, each time Santa takes a break, he changes the white blouse he wears under his suit jacket, and the suit itself lasts only a couple of days -- at most -- before being dispatched to the dry cleaner's.

"It's a big job to keep Santa sparkling. We have a dry cleaner sworn to secrecy," Rutan explains. Ever conscientious, Santa also changes gloves constantly. "We try to stop the germs spreading from one kid to another. The same parent who pulls a kid out of school for no reason, thinks nothing of sending a kid with a 103-degree fever to see Santa," Rutan says. "We use the same type of white gloves they use for the West Point cadets: They're flexible, sturdy, and stand up to lots of washing."

Seemingly ubiquitous -- Macy's Santa has the magical ability to appear simultaneously at up to six different workshops inside the New York Santaland alone -- and supernaturally spotless, Santa relies on 30 identical everyday suits and four flight suits in steady rotation from Thanksgiving through Christmas Eve. "We select the materials for durability. One outfit will last three or four years," says Rutan, a veteran of Christmas at Macy's since 1991. "We stock five fresh outfits every year."

Though the elves' outfits come and go, the last major revamp of Santa's costume came in the late 1970s, when Macy's then vice president and director of special productions, Jean McFaddin, updated Santa to look more old-fashioned. Since then, Macy's brass has repeatedly rejected attempts to put Santa in closer touch with his times. Rutan recalls that "back when we were doing Spiderman and Batman, there was also a modern superhero design submitted for Santa."

That was nixed too. "People relish the tradition. We've been doing the parade since 1924, and people have a certain expectation," says Rutan, although he willingly admits that Santa's suit hasn't always been the same. "Back in the teens and '20s, his robe was almost ankle-length. Going back to the 1800s, I have postcards of him wearing green or blue or brown or even yellow ... Ultimately Santa's image is now ingrained in the American consciousness."

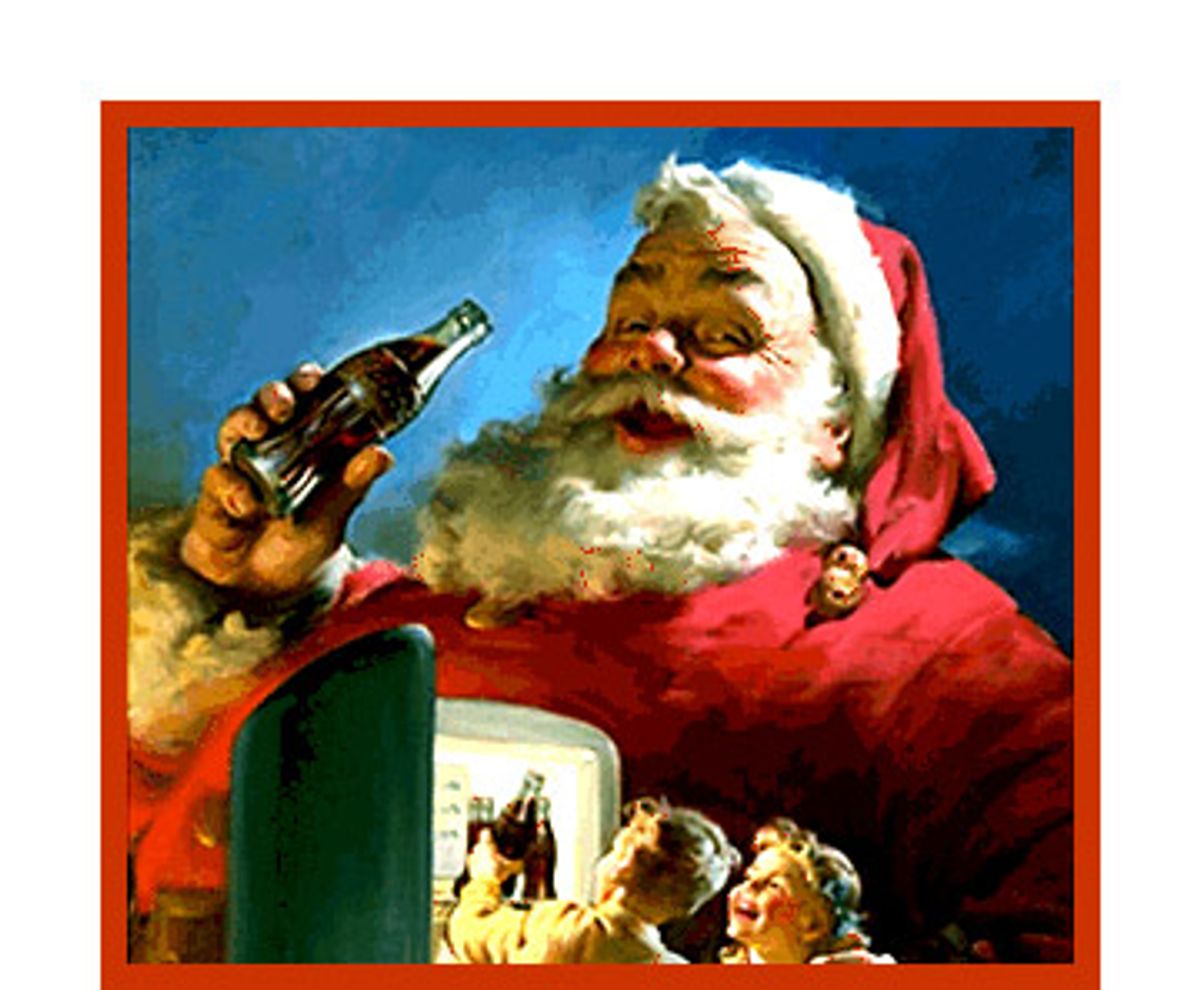

Macy's doesn't attempt to take all the credit for that. As Rutan says: "It was really the Coca-Cola advertising of the 1930s that solidified the red suit and spread the image."

His eyes how they twinkled! His dimples how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

"The Coca-Cola Santa is not an elf," explains Coke archivist Phil Mooney. "He's a big, happy guy with a twinkle in his eye. He's a synthesizer. Unlike previous interpretations, this Santa really gets into the fun of the season: He's not so strict as the Nast illustration. You see him going to the refrigerator to steal a turkey leg."

Celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Santa first rendered by Haddon Sundblom in 1931, Coca-Cola is currently sponsoring an exhibit of 20 of Sundblom's original oils at Jazz at Lincoln Center's Frederick P. Rose Hall in New York City. The company has also revived a Sundblom Santa and put him back its holiday Coke cans. "Originally our Santa advertising came about when Coca-Cola was looking for a way to turn a drink that was associated with warm weather into a holiday beverage," explains Mooney, who's been with the company 29 years. "Who better than Santa?"

Sundblom was not the first to draw Santa for Coca-Cola: In 1930, illustrator Fred Mizen came up with an image showing Santa standing at a department store soda fountain. As Mooney says, it "made Santa just look like a guy in costume." But "Sunny" Sundblom, who also invented the happy Quaker on the Quaker Oats logo, had a magic touch with twinkling eyes, rosy cheeks and wholesome corpulence. (His last-ever assignment, executed at age 73, was the December 1972 cover of Playboy showing a blonde busting out of her Santa suit.)

"Post-World War II, when Coke became global, Santa was exported all through Western Europe and Hong Kong. We used him on packaging, advertising, billboards, point-of-sale materials ... all media," Mooney says. "Then during the mid-1960s, we began to move away from print advertising and Santa didn't move well."

Sundblom drew his last Santa for Coca-Cola in 1964. As Mooney puts it: "At that point, when we stopped Santa, we sort of lost our equity in Christmas."

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard on his chin was as white as the snow.

Because Santa was an uncopyrighted character, Sundblom's rendering was only one of many in what amounted to a Santa Claus media blitz during the 1920s and 1930s. Aside from being a predictable perennial for the Saturday Evening Post and a slew of other large-circulation magazines, Santa also shilled for Maxwell House coffee, Martini vermouth, Dewar's scotch, White Label scotch, and Guinness stout -- plus GE refrigerators, Whitman's chocolates, and virtually any toy manufacturer with enough money to buy ad space. After the war, it only got worse. Santa added accounts like Budweiser and Pepsi, which often put him in direction competition with himself.

Then the backlash began. In 1946, fed up with the commercialization of Christmas, screenwriter Valentine Davies started a script called "Miracle on 34th Street." A native New Yorker, Davies looked to the original and best-loved Santa-- that is, the Macy's version -- and set his story in Manhattan. His plot is set in motion by real estate envy. The romance between two busy professionals is made possible by the proximity of their apartments, and his sweet little heroine is also a precocious smartass who considers herself far too sophisticated for fairy tales. The divorcée played by Maureen O'Hara starts off declaring, "I think we should be realistic and completely truthful with our children" but is soon made to see the error of her ways. When another Santa is too drunk to snap his whip, Kris Kringle is pressed into parade service and then hired full-time because "he's a born salesman." Handed a list of Macy's overstocks to unload, Kringle instead initiates a goodwill campaign, which promptly lands him in Bellevue on a psych charge. Then, in a courtroom cliffhanger, complete with a pusillanimous judge fearing a political backlash from toy and candy workers' unions, Kringle's case is made by a post office employee eager to unload all the dead letters addressed to Santa. For the grand finale, Kringle proves his miraculous powers by getting the single mother remarried and finding the new family an ideal and affordable house in the suburbs.

Davies' anti-commercial parable was a commercial success -- and it won Edmund Gwenn,, the 5-foot-5-inch Welshman who played the right jolly old elf, the 1947 Academy Award for best supporting actor. Davies himself was able to grind out a novelization of his screenplay in time to cash in on the movie. And Macy's, which allowed Gwenn to be the guest grand marshal of the Thanksgiving Day parade in 1946 for the filming and again in 1947 to promote the film, is still reaping publicity long after Gimbel's, Stern's, McCreery's and most of the other stores mentioned in the movie have ceased to exist. To this day, Macy's uses a movie-style marquee to spell out "Santaland Now Open," and it posts plenty of factoids about "Miracle on 34th Street" -- the movie was filmed in 22 days, half the extras came from Macy's -- at the entry to the line, so kids can take in its anti-materialistic message as they wait to tell Santa what toys they want for Christmas.

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath.

The heavy smoking that goes on in "The Night Before Christmas" and is omnipresent in the Nast illustrations is a no-no now. Gone are the days when Santa hawked Lucky Strikes. "Actually we never included the smoking," says Mooney, the Coca-Cola archivist. "Coke never advertises another product. When you're selling one thing you don't want to show another one."

Macy's helped Santa kick the habit "back in the 1950s," says Rutan. "That's when lots of other icons -- Nat King Cole, Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper -- were passing away from cigarettes. Santa didn't want to set a bad example for the kids. So, like Roy Rogers, he quit cold turkey."

Santa has an image to maintain. He doesn't eat or drink on the job. He doesn't appear in déshabillé. Journalists are barred from Santaland. "'Miracle on 34th Street' made Macy's a known quantity that we carefully maintain," Rutan says. "We've had a woman as old as 112. We've had babies come on their way home from the hospital. This year, we've already had two adults ask for the safety of their family members in Iraq.

"They think that if they ask the guy in the red suit, maybe it might happen."

He had a broad face and a little round belly

That shook when he laughed like a bowl full of jelly.

"The Coke Santa Claus was really rotund. Santa's gotten a little less fat lately, but you can't change him too much," says illustrator Robin Richesson, who worked on both the "dignified, columnar ... father figure" in "The Polar Express" and the "new age-y Santa" in "The Santa Clause 2," in addition to rendering her fair share of commercial Santas. "In the early part of the century he may have been allowed to wear blue, but not now ... At this stage, in America at least, that has gotta be a red suit, a matching hat, a white beard and boots. Take one away, and people won't recognize him."

Like James Bond, Santa is a superhero who can change only within certain limits. Santa can't be sexy. Santa can't be chic. Santa can't be skinny. (Coca-Cola has never used Santa to advertise Diet Coke.) Too much trendiness, and Santa turns into a joke. (Think Saks Fifth Avenue's 2004 bespoke-suited metrosexual model or its 2005 Dsquared2 ambisexual version.)

Ergo, at Macy's, even a beard trim becomes a very big deal: The let-it-all-hang-out shagginess he sported in the '70s has been trimmed back to the approximate length of the facial hair worn by the extremely dignified Edmund Gwenn. As Richesson says: "Santa's not some silly fat guy gnawing on the turkey leg anymore. People want him to be more suave. More noble." Richesson puts that down to a celebrity-crazed culture "where even Santa has been glamorized because we're so very image conscious."

"But then he'll always be changing a little bit, because people project on him whatever they want and need at the time," she says.

"That's what's made him such a magical guy."

Shares